The Conciliation Bill: 1910-1912

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (1)

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (2) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (3)

1910 Conciliation Bill

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (4)

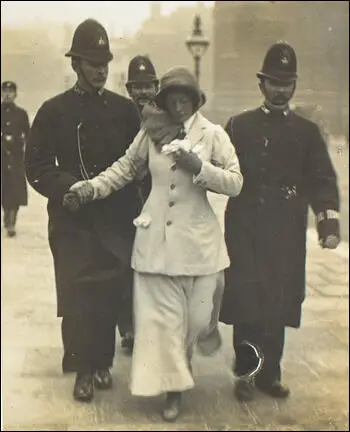

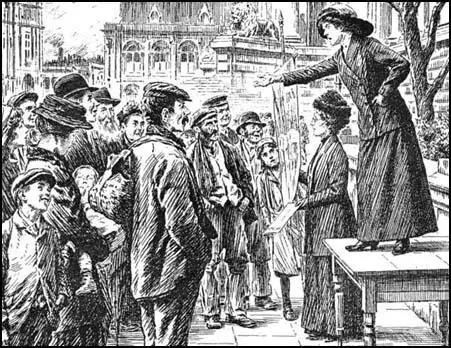

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (5)

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (6) This included Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Gladys Evans, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Patricia Woodcock, Vera Wentworth, Florence Canning, Mary Clarke, Henria Williams, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Minnie Turner, Lucy Burns and Grace Roe. (7)

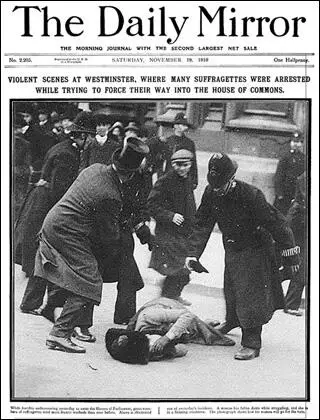

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened on what became known as Black Friday: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse." (8)

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers." It was claimed that two women, Cecilia Wolseley Haig and Henria Williams, died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries. Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st." (9)

The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. (10) Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent." (11) Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police." (12)

Sylvia Pankhurst believed that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had encouraged this show of force. "Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought. I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated." (13)

Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (14)

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report Treatment of the Women's Deputations of November 18th, 22nd and 23rd, 1910, by the Police (1910) on Black Friday. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel." (15)

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". (16) However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct." (17)

Henria Williams, who had been on the demonstration died on 2nd January 1911. Her brother wrote: "She died while actively engaged in furthering the cause which you have so deep at heart. From our long conversations and correspondence, it is beyond doubt that my sister was fully aware that she was affliction of the heart and the work she was doing was exceedingly dangerous. Nevertheless, she willingly and zealously persisted in doing whatever she could, and on several occasions expressed herself as quite prepared to make the sacrifice of some years of her natural life." (18) Sylvia Pankhurst claimed that Henria Williams died because of the beatings she endured that day. "Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st." (19)

Cecilia Wolseley Haig died on 31st November 1911 at her home address at 7 Brook Street, London, Middlesex. (20) Sylvia Pankhurst claimed that she died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries." (21)

1911 Conciliation Bill

The general election of December, 1910, produced a House of Commons which was almost identical to the one that had been elected in January. The Liberals won 272 seats and the Conservatives 271, but the Labour Party (42) and the Irish (a combined total of 84) ensured the government's survival as long as it proceeded with constitutional reform and Home Rule. This included the Labour Party policy of universal suffrage (giving the vote to women on the same terms as men).

Winston Churchill, a senior figure in the Liberal government had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (22)

Under pressure from the Women's Social and Political Union, in 1911 the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. According to Lucy Masterman, it was her husband, Charles Masterman, who provided the arguments against the legislation: "He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to and began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that 'fallen women' would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself...He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food." (23)

Churchill argued in the House of Commons: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife.... What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters?" (24)

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he had told his close associates, such as Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP in West Ham North: "He (David Lloyd George) was very much disturbed about the Conciliation Bill, of which he highly disapproved although he is a universal suffragist... We had promised a week (or more) for its full discussion. Again and again he cursed that promise. He could not see how we could get out of it, yet he regarded it as fatal (if passed)." (25)

Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill." (26)

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose." (27)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament. (28)

On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians such as H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged." (29)

The following month Millicent Fawcett wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them." (30)

1912 Conciliation Bill

Henry Brailsford went to see the Emmeline Pankhurst and asked her to control her members in order to get the legislation passed by Parliament. She replied "I wish I had never heard of that abominable Conciliation Bill!" and Christabel Pankhurst called for more militant actions. The Conciliation Bill was debated in March 1912, and was defeated by 14 votes. Asquith claimed that the reason why his government did not back the issue was because they were committed to a full franchise reform bill. However, he never kept his promise and a new bill never appeared before Parliament. (31)

Ray Strachey, the author of The Cause: A History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928) pointed out that Millicent Fawcett now lost complete confidence in the Liberal Party to give women the vote: "Nothing more was ever hoped for the Liberal Party. The only prospect of successful lay in a change of Government, and to this end the women now devoted their energies." (32)

In early 1912 Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to form an electoral alliance with the growing Labour Party, as it was the only political party which really supported women's suffrage. "It soon strengthened that alliance, setting up a special Election Fighting Fund in May-June so that the NUWSS could help Labour candidates more effectively at by-elections." (33)

The WSPU responded by organising a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU. (34)

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Foot, The Vote (2005)

Henry Brailsford started from the undeniable fact that the vast majority of Members of Parliament, even after the 1910 elections, favoured votes for women in some measure. Surely, he reflected, a deal could be arranged so that majority could be converted into enfranchising legislation. Tirelessly, he put together what became known as the Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement. The Committee cobbled together a Conciliation Bill that would grant the vote to some women. Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and the Pethick-Lawrences were suspicious of the new Bill but did not oppose it. Reluctantly, they agreed a temporary truce in which all militant activities, including byelection campaigning against Liberal candidates, would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear.

The Pankhursts' suspicions were firmly based. The Bill was infected by the rotten compromises that had dogged so many similar measures in the past. Under its provisions, married women were barred from voting in the same constituency as their husbands. Lodgers, too, had no vote - a restriction that especially shocked Emmeline Pankhurst. Far too many concessions, she complained, were made to the Tories on the Committee, all of whom were terrified by the spectre of universal suffrage. Nevertheless, the truce held. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Bill was carried by 109 votes, and immediately sent to a committee of the whole House, thus ensuring that at least until the second general election of 1910 it was doomed. Studying the division lists, Brailsford and his colleagues were surprised to see the name of Rt. Hon. Winston Churchill, Home Secretary, as an opponent. Churchill had given an assurance to the Conciliation Committee that he would support the Bill, and had even allowed his name to be published as a supporter. Brailsford had the first clear sign of the duplicity of the Liberal politicians with whom he was dealing.

In November 1910, in protest at the failure of the first Conciliation Bill, Emmeline Pankhurst convened a huge meeting and enjoined the audience to "come with me to the House of Commons". Hundreds of women followed her. It looked as though the truce was at an end, but the brutality of the police that evening was disgusting enough to swing the pendulum of public opinion towards the protesters. Brailsford himself took charge of the collection of evidence from the demonstrators. His report contained enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely. Its impact went way beyond the bounds of the Woman's Press, which had commissioned it. The report, and the new Liberal Government that took office after the election of December 1910, also bought more time for the WSPU truce on militancy. The truce held while a new Conciliation Bill was published without the £10 property qualification for voting that had been in the first Bill, and without an express ban on husbands and wives voting together. In a sudden surge of public and parliamentary enthusiasm, the second reading of this Bill passed the Commons on 5 May 1911 with a majority of 167, and for a brief moment it seemed to Brailsford, Nevinson and company that their prodigious negotiations had been worthwhile:

They were reckoning without top Liberal politicians, in particular the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George. Lloyd George loved high office. He was not remotely interested in votes for women, and he regarded the campaigners, especially the militant ones, as an infernal nuisance. On the other hand, he understood that the Conciliation Committee posed a problem for the Government. A Commons majority of 167 could hardly be ignored, especially when the Bill had been passed two years running. But Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Tory Party. The problem called for what Lloyd George would have described as diplomacy, but quickly turned out to be duplicity. After stalling the WSPU all through the summer, Lloyd George started secret discussions with Brailsford and the Conciliation Committee. On 7 November 1911, he told the Committee he would support the Conciliation Bill if another Bill to introduce manhood suffrage failed. No such Bill had even been suggested, but, as if by magic, the following day Prime Minister Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise most men - a Bill that, he promised, could be amended to include women.

(2) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931)

A ninth "Women's Parliament" was called for Caxton Hall on November 8th. It was dramatically timed. Ten days before, Asquith had disclosed the breakdown of the House of Lords Conference; the Parties had refused to agree. Whilst the women were assembling in the Caxton Hall, he announced his intention to dissolve Parliament ten days later, and to take all the time of the House for Government business. Keir Hardie requested two hours to discuss a resolution that the Government should leave time for the Conciliation Bill. Asquith promised to answer him in a few moments, but left the House without doing so.

Meanwhile three hundred women, in detachments of twelve, were approaching. Mrs. Pankhurst, Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, one of the earliest women doctors, first of the Women Mayors and sister of Mrs. Fawcett, Hertha Ayrton, the scientist, Mrs. Cobden Anderson, three aged women : Miss Neligan, Mrs, Soul Solomon, and Mrs. Brackenbury, and the Princess Dhuleep Singh. Mrs. Pankhurst and this first company were allowed to reach the House and even taken to the Prime Minister's room; unable to see him, they returned to the Strangers' Entrance, Members of Parliament flocked out to speak to them - Lord Castlereagh moved an amendment on the lines of Keir Hardie's motion. It was debated for an hour; only fifty-two Members voted for it, but it drew from Asquith a promise to state on the following Tuesday his Government's intentions respecting Votes for Women. In the throes of the constitutional crisis, with the struggle of Nationalist Ireland versus Ulster driving the country towards civil war, Votes for Women was in the forefront of the stage: a triumph indeed for the militants. Outside in the Square were scenes of unexampled violence. I had promised to report the affair for Votes for Women, and I was obliged to avoid arrest as I was writing a history of the militant movement under contract with the publishers.

With Annie Kenney I took a taxi and drove about, the driver nothing loath to make his way into the throng. Finding it unbearable thus to watch other women knocked about, with a violence more than common even on such occasions, we jumped out of the taxi, but soon returned to it, for policemen in uniform and plain clothes struck us in the chest, seized us by the arms and flung us to the ground. This was the common experience. I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her. Two girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two uniformed policemen. One of a group of officers in plain clothes ran up and kicked one of the girls, whilst the others laughed and jeered at her.

(3) Robert Lloyd George, David & Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2005)

Churchill and Lloyd George had radically different attitudes towards women and these coloured their approach to demands for suffrage. Churchill's may be characterised as Victorian: perhaps because of his parents' unconventional private lives, he reacted by becoming, if not prudish, at least reserved with young women. He showed a healthy romantic interest in music-hall actresses, and later in Pamela Plowden, among other young ladies, but did not enter into a full relationship until, at the age of thirty-four, he married Clementine Hozier. Lloyd George, on the other hand, had an active sex life in Criccieth and later in London. This reflected the difference between the "natural" approach of growing up in the Welsh countryside and the artificial environment of an all-male public school and the Army.

Churchill's attitude to women was one of old-fashioned chivalry... In the eyes of the young Winston, woman was on a pedestal.

During his military service in India, Churchill commented on the parliamentary debate on women's suffrage; which he studied in the Annual Register.... "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." It was a reactionary sentiment fully in accord with those of his fellow cavalry officers in the Raj.

Even a decade later, in 1906, after he had joined the Liberal Party and begun to absorb and express fairly radical opinions about reform, Churchill still responded to his constituents in Manchester (a staunchly Liberal area) on the matter: "I am not going to be hen-pecked (thus coining the word) on a question of such grave importance." And instead of dealing with the demands of the suffragettes who disrupted his political meetings, he avoided the question by saying, "We must observe courtesy and chivalry to the weaker sex."

When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby."

Nevertheless, it is noticeable that after his marriage to Clementine, his view of women began to change. He became more liberal and more worldly. His colleagues in the Liberal Cabinet, however, continued to tease him that his carefully prepared speeches were often interrupted by "What about votes for women, Mr Churchill?"

(4) Lucy Masterman, C. F. G. Masterman (1939)

Winston Churchill and Charlie (Charles Masterman) had a very curious morning over the Conciliation Bill. He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to, nor did Lloyd George. So Charlie began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that "fallen women" would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself. (The result was a speech of such violence and bitterness that Lady Lytton wept in the gallery and Lord Lytton cut him in public. Charlie thinks that his mind had up till then been in favour of the suffrage but that his instinct was always against it. He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food. At the end the instinct had completely triumphed over the mind.)

(5) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (12th July, 1910)

I have been making as good an examination as is in my power of the actual proposals, and shape, and character of the Conciliation Bill. The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons. I have only to turn to what we have heard quoted frequently in the Debate—namely, Mr. Booth's figures in regard to London, on which the hon. Member for Merthyr (Keir Hardie) relies so much. Out of the 180,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? Half of these voters are persons who have not to earn their living. At any rate only half of them are workers. I say, in any case, the distinction shows quite clearly that the proportion prevailing in the new electorate is wholly disproportionate to the proportion which exists now between propertied and non-propertied classes generally throughout the country. That is not denied. Take the figures on the hon. Gentleman's own interpretation. What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters? After all we are discussing a real Bill, and we are entitled to know what it is we are asked to commit ourselves to. I want the House to consider very carefully the effect of this on plural voting. At present a man can exercise the franchise several times, but he has to do it in different constituencies. But under this Bill, as I read it, he would be able to exercise his vote once or twice or three times in the same constituency if he were a wealthy man. If he had an office and residence in the same constituency he has only one vote now, but if this Bill passed he could vote for his office himself, and he could give his wife a vote for his residence. If a man votes in respect of town and country properties, under this Bill he could give one vote as his wife's occupation qualification; one qualification to his daughter, and he could keep his own vote for a property qualification elsewhere. If he owned a house and land he could keep one vote for the land for himself, and put his wife in for the house. If he owned a house and stable, or other separate building, then under this democratic Bill brought forward by the hon. Member for Blackburn he could give one vote to his wife in respect of the house, and take the other himself in respect of the stable.

(6) The Spectator (18th February, 1911)

The supporters of Woman Suffrage are counting the number of votes likely to be cast for their cause in the House of Commons, and so exhilarating do they find the occupation that the figures grow at every attempt to look into the future. For our part, we believe that the " pledges " said to have been given by members are in most cases so ambiguous that they have no determinable value, and the predictions of the Suffragists are consequently scarcely worth the paper they are written on. We do not mean that members have actually expressed sympathy with Woman Suffrage while intending secretly to work against it; we bring no charge of dishonesty. It is quite possible that a majority of the present House have a general sympathy with the principle, but it is quite another matter to bring that sympathy into operation. It would fade away before a Bill which did not satisfy the hundred and one scruples and reser- vations that exist side by side with a sincere enough attach- ment to the cause of Woman Suffrage. There is the widest difference in the world between accepting a principle and ac- cepting a particular Bill. Although we do not suppose that any member has been dishonest in giving assurances, we have always thought, and will say again, that a good many members have trifled with the question; they have not appreciated the fact that Woman Suffragists are perfectly sincere, and in the result they have behaved very unfairly to them. Particularly is it the duty of the Government to say exactly what their attitude towards Woman Suffrage is without casuistry or ambiguity. We ourselves are funda- mentally and unfalteringly opposed to Woman Suffrage for reasons which we need not repeat. We do not expect Suffragists to like what we say, but at least they cannot accuse us of unfairness or levity. Every member of the House of Commons, from the Prime Minister downwards, ought to make up his mind to declare his opinion in the plainest possible terms either against Woman Suffrage or in favour of it, recognizing that this is not one of those questions which can be treated as a kind of annual Parliamentary joke. It excites far too much social disquiet for that. The prospect in the present session is that Sir George Kemp, who has got the first place in the ballot for private members' Bills, will bring in a revised form of the " Conciliation " Bill as soon as private members are given a day. This may or may not happen after Easter. In its altered form the " Conciliation " Bill will omit the £10 qualification, and provide that husband and wife, though they may both have votes, may not vote in the same constituency. The whole Bill, moreover, will be open to amendment. The Suffragists hope that if they get the Bill read a second time after Easter they will be able to demand " facilities " from the Government. It is important to know in what spirit the Government would meet that demand. Mr. Asquith, as everyone will re- member, said that during the present Parliament the Suffragists ought to have the opportunity " effectively " to proceed with a Bill which is open to amendment. We do not, of course, expect him to ignore a promise, but we do expect him, also, if the occasion should arise, not to forget his responsibility to the country as Prime Minister. He believes that the results of Woman Suffrage would be deplorable. Very well, he would not be mindful of his great trust if he let his strong convictions remain without influence on the course of the debate. He can give the House the opportunity to pass the Bill if it wishes, but he should also try definitely to direct opinion in the only safe course for the country. Since the " Conciliation" Bill passed its second reading in the last Parliament by a larger majority than any Government measure enjoyed, the opinion of certain members of the Government has, fortunately, hardened a good deal against Woman Suffrage. Mr. Churchill has, to all intents and purposes, thrown it over. When he received a deputation of Suffragists at Dundee, he said that he would never vote for a Woman Suffrage Bill unless he were assured that the country was in favour of the principle of Woman Suffrage. Asked how he would discover the opinion of the country, he replied that he did not as a rule believe in a referendum or plebiscite, but that he held Woman Suffrage to be one of the few questions in which a referendum would be admissible. This means that if Mr. Churchill waits for a popular declaration in favour of Woman Suffrage he will wait for ever, for nothing is more certain than that the country dislikes the very thought of Woman Suffrage. Now Mr. Churchill has said in the House of Commons that the "Conciliation" Bill was not democratic enough for him - that he must wait for a Bill of a wider sweep. In the estimates of the number of Suffragists in the present House he is very likely reckoned therefore as belonging to the advanced school of Suffragists. This one example will show how utterly misleading the estimates are. Mr. Lloyd George has not abandoned the Suffrage cause quite so plainly as Mr. Churchill, but at the election he said that the education of the country to believe in Woman Suffrage was a necessary preliminary to passing any measure in Parliament. We think we may safely prophesy therefore that, even if the "Conciliation" Bill is re-introduced this Session, at least two powerful voices on the Front Bench must be raised against it.

We have said that the thought of Woman Suffrage is strongly disliked in the country. This is proved by the remarkable results of a canvass of women municipal electors - virtually the class to which the "Conciliation" Bill proposes to give the Parliamentary vote - conducted by the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage. Would it not be heading for national inefficiency and disaster, would it not be madness, to give the franchise to a class which declares that it does not want it? Was ever a thing comparable to this proposed before? The figures of the canvass to which we refer are being published month by month in the Anti-Suffrage Review, the organ of the National League. According to the latest figures 18,850 of those who have been canvassed have declared themselves opposed to Woman Suffrage, and only 5,579 in favour of it, while 4,707 said that they were indifferent and 12,621 have not answered. As the Anti-Suffrage Review says, is it reasonable to suppose that of those who have not answered probably the vast majority are opposed to votes for women, for it is not to be supposed that many Woman Suffragists would fail to make known the faith that is in them. Mr. Balfour has said that his inclination towards Woman Suffrage is induced by his belief in like principle of " governing by consent," and that if it were proved that women themselves did not want to vote his opinion would be greatly modified. We trust that these figures will have their due effect upon his mind. We ought to say before passing on that the value of the figures has been challenged by Suffragists, who contend that unfair arguments were used by the canvassers. We understand that so far as possible the questions were put to the women municipal electors by postcard, in order to avoid this charge of undue influence. Let us, however, state the objection. It is admitted that a proportion of the answers were collected by personal can- vassers. The last number of the Anti-Suffrage Review contained an account of a canvass of men and women at Hawkhurst, in Kent, conducted under ideal conditions, for the Suffragists were taken into the confidence of the Anti-Suffragists, and representatives of both sides managed the canvass and audited the figures. No arguments whatever were used by either side. The result makes one think that the figures of the larger canvass published by the National League are not very misleading.