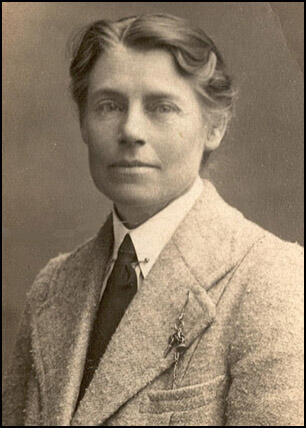

Evelina Haverfield

Evelina Scarlett, the youngest daughter of William Frederick Scarlett, the 3rd Lord Arbinger, was was born at Inverlochy Castle on 9th August 1867.

Evelina married Major Henry Haverfield in 1887 when she was 19. He was 20 years her senior. They moved to Dorset and over the next few years she had two sons.

Henry Haverfield died in 1895. She remarried another soldier, Major John Blaguy, in July 1899, but reassumed the name "Haverfield" by deed poll within a month of the marriage. An excellent horsewomen, she accompanied her new husband husband to South Africa when he fought in the Boer War.

An early member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies she joined the Women's Social and Political Union in March 1908. She later explained that she joined the WSPU after hearing Minnie Baldock speak at a public meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst recalled: "When she first joined the Suffragette movement her expression was cold and proud... I was repelled when she told me she felt no affection for her children."

Evelina's marriage to Major John Blaguy was not a success. According to her biographer, Boyce Gaddes: "After about ten years of this tentative relationship, they apparently each went their own ways, legally married but permanently separated."

In 1909 Haverfield joined Annie Kenney, Mary Blathwayt and Elsie Howey to organise the women's suffrage campaign in the West Country. During this period she became honorary secretary of the Sherborne branch of the WSPU. She retained her membership of the NUWSS and in June 1909 took part in its caravan campaign with Isabella Ford and Ray Strachey.

WSPU Militant Campaign

On 29th June 1909 she was arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst during a demonstration outside the House of Commons. Although she was defended in court by Lord Robert Cecil she was found guilty and fined. The case went to appeal but was dismissed in December and the fine was upheld.

Evelina Haverfield, along with Vera Holme and Maud Joachim, was a mounted marshal for a WSPU procession on 22nd July 1910. On 18th November 1910, she was charged with assaulting a policeman by hitting him in the mouth. In court it was reported that Haverfield had said during the assault that she had not hit him hard enough and that "next time I will bring a revolver." She was sentenced to a fine or a month's imprisonment. She did not go to prison as her fine was paid without her consent. Three days later she was arrested for trying to break through a police cordon outside the House of Commons. This time she was sent to Holloway Prison for two weeks.

East London Federation of Suffragettes

In 1910 Haverfield joined the Tax Resistance League. The following year she began living with Vera Holme. It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Holme was a lesbian and the lover of Haverfield. This view is supported by Emily Hamer, the author of Britannia's Glory: A History of Twentieth-Century Lesbians (1996) who claims that the bed they shared was inscribed with their initials.

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire.Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, disagreed with this arson campaign. When Pethick-Lawrence objected, she was expelled from the organisation. Others like Haverfield, Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford and Louisa Garrett Anderson showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU and Hertha Ayrton, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed funds for the organization.

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Haverfield, Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Sylvia claimed that Haverfield had changed greatly over the last five years: "During her years in the Suffrage movement her sympathies so broadened that she seemed to have undergone a rebirth."

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, Haverfield supported the decision by Emmeline Pankhurst, to help Britain's war effort. In 1914 Haverfield founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Christabel Marshall described Haverfield as looking "every inch a soldier in her khaki uniform, in spite of the short skirt which she had to wear over her well-cut riding-breeches in public."

Appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps, Haverfield was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia. On 5th July, 1916, Elsie Bowerman wrote to her mother: "Mrs Haverfield has just asked me to go out to Serbia at the beginning of August, to drive a car - May I go? I know Miss Whitelaw would let me off Wycombe to go. It is what I've been dying to do & drive a car ever since the war started. I should have to spend the week after the procession learning to drive - the cars are Fords - if I went I would come home when I come back I would not have to go to W.A. It is really like a chance to go to the front. They want drivers so badly. So do say yes - It is too thrilling for words."

In August, 1916, Haverfield went with Dr. Else Inglis, Elsie Bowerman, Nina Boyle, Lilian Lenton and the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia. Haverfield's partner, Vera Holme, was commissioned as a major and was placed in charge of horses and trucks in the unit.

Haverfield was appointed head of the transport column and in August 1916 she was dispatched to Russia. Her biographer, Elizabeth Crawford, has commented: "Haverfield sailed for Russia, in charge of the unit's transport column, which comprised seventy-five women noted for their smart uniforms and shorn locks. She herself is invariably described as being small, neat, and aristocratic, able to command devotion from her troops, although some of her peers, not so enamoured, were scathing of her ability."

In March 1917 she left her post after a disagreement with Dr. Else Inglis. She later wrote: "I hope the Committee will realize that though Mrs. Haverfield and I differed over the plans for the future, there isn't a particle of ill-feeling between us. Mrs. Haverfield is as generous and open-minded and as ready to face facts as she always was. All we either of us care about is the success of the unit - and our ideas differ... The Committee must decide between us! - Anyhow they may be thoroughly proud of the work the Transport has accomplished."

With Flora Sandes she founded the Evelina Haverfield's and Flora Sandes' Fund for Promoting Comforts for Serbian Soldiers and Prisoners. After the armistice Haverfield founded an orphanage in Serbia and was working there when she contracted pneumonia and died on 21 March 1920 at Bajina Bašta, where she was buried. In her will she left Vera Holme £50 a year for life.

Primary Sources

(1) Evelina Haverfield, diary entry (8th July, 1899)

I married Major Balguy R.A. with no intention of changing my name or mode of life in any way. He is an old friend of my darling Jack's. The ceremony took place at Caundle Marsh Church in the presence of Mrs. C., my parlour boarder, and of Shepherd, my groom.

(2) Boyce Gaddes, Evelina Haverfield (2009)

Evelina was active in the women's suffrage movement for many years, first joining the moderate suffragists who patiently pursued legal avenues open to them, and later the militant suffragettes who got the public's attention by waging war on the government.

She participated with the militants for about four years, and took part in a number of street battles with the London police, one major court battle, and a giant street parade. During those years she was arrested, imprisoned, and fined a number of times for obstructing and assaulting the police, and for leading the police horses out of their ranks.

If she believed in a cause, she would support it with unstinted effort.

She was involved in a legal attempt to effect a meeting with Prime Minister Asquith on June 29,1909. This event became known as the Bill of Rights March because Mrs. Pankhurst, leader of the militant suffragettes, led a deputation of eight well-known and respected ladies in an effort to reach the House of Commons.

Each lady carried a copy of a petition based on an ancient Bill of Rights statute. Evelina was one of this group. They were followed by a large number of other suffragettes each carrying a copy of the petition.

All were blocked by the police from entry in to the House of Commons. In the subsequent confrontation with the police, more than one hundred women, including all of Mrs. Pankhurst's group, were arrested and removed to the police station.

They all appeared in Police Court the following morning. Mrs. Pankhurst and Evelina were put in the dock together, and were treated as a test case for the dozens of others arrested. Evelina was defended by Counsel who claimed that she had been wrongfully arrested in the exercise of a constitutional right.

Because of the strength of her defence, the Government felt some uncertainty on this point of law, and delayed their reply. In the end, the Government fined both women, but the case brought to a wider public's attention the prejudice of the Asquith administration, and the justice of the women's petition.

(3) Dr. Elsie Inglis reported on why Evelina Haverfield resigned in March 1917.

Some of the girls had not had a change of underclothing during the retreat. I tried to make Mrs. Haverfield see that she was working for failure along those lines, and that the fact that men don't take off their clothes for a fortnight in the trenches had nothing whatever to do with women's army ambulance work. I took one case of flagrant injustice and make her see that you can be a beast but you must be a just beast.

(4) Dr. Elsie Inglis, letter to the London Committee (March, 1917)

Notwithstanding these difficulties the work the Transport has accomplished is wonderful - and the work has been possible mainly owing to the staying power and grit of its Commandant. She is not a person easily beaten either by internal or external difficulties... I hope the Committee will realize that though Mrs. Haverfield and I differed over the plans for the future, there isn't a particle of ill-feeling between us. Mrs. Haverfield is as generous and open-minded and as ready to face facts as she always was. All we either of us care about is the success of the unit - and our ideas differ... The Committee must decide between us! - Anyhow they may be thoroughly proud of the work the Transport has accomplished.

(5) Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain (2007)

Other wartime occupations actively encouraged younger unmarried women recruits and a number of women who made a significant contribution to the war effort through their work were in relationships with other women. It is difficult to interpret the precise nature of women's close friendships in the absence of explicit evidence as to how the women themselves viewed them, however. Dr Elsie Inglis, founder of the SWH, had lived with Dr Flora Murray for a number of years in Edinburgh, and Drs Louisa Martindale and Louisa Aldrich-Blake also lived with women. Emily Hamer argues that Evelina Haverfield, founder of a number of women's Voluntary organisations, including the Women's Emergency Corps and the Women's Volunteer Reserves, was a lesbian and lover of the former suffragette Vera 'Jack' Holme. The two women worked closelv with Dr Elsie Inglis in Serbia during the war, and when Haverfield died in 1920, Holme staved in Serbia working as an ambulance and relief lorry driver.

(6) Emily Hamer, Britannia's Glory: A History of Twentieth-Century Lesbians (1996)

After Evelina Haverfield's death Vera Holme had to remove her belongings from the home in Britain which they had shared; the house had been owned by Evelina. Vera sent a list of her belongings, which were to be returned to her, to the executors of Haverfield's estate. A copy ot this list survives among Vera Holme's papers. Among the things that Vera Holme wanted back were presents that she had given to Evelina and things with particular sentimental value. Chief amongst these was "1 bed with carved sides (inscribed with) E.H. and V.H.