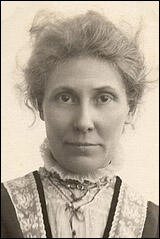

Minnie Baldock

Minnie Rogers was born in London on 20th November 1864. As a girl she worked in a shirt factory. After her marriage to Harry Baldock she had two sons, Jack and Harry. She was a member of the Independent Labour Party and her husband was a local councillor in West Ham. During this period she became friends with Dora Montefiore and Charlotte Despard.

Along with Keir Hardie, her local MP, she held a public meeting in 1903 to complain about the low pay of women in the area. She was also involved in the administration of the West Ham Unemployed Fund. In April 1905, Baldock became an ILP candidate in the election for the West Ham Board of Guardians.

Baldock joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and on 19th December 1905 she joined forces with Dora Montefiore and Annie Kenney to heckle Herbert Asquith, while he was making a speech in Queen's Hall. Baldock joined with Kenney to repeat the performance when Henry Campbell-Bannerman appeared at a Liberal Party rally at the Royal Albert Hall on 21st December. They were ejected but not arrested. The following day Baldock, Kenney and Teresa Billington-Greig, called on Campbell-Bannerman at his house at Belgrave Square. He told them that he would be dealing soon with the question of women's suffrage.

On 29th January 1906, Baldock established the Canning Town branch of the WSPU. It was an attempt to recruit working-class women to the cause. Over the next few months Baldock arranged for Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Flora Drummond, Dora Montefiore, Selina Cooper, Teresa Billington-Greig and Marie Naylor to address the members of the group.

On 23rd May 1906, Dora Montefiore sent her a postcard saying: "Am resisting bailiff who has come to distrain for income tax, and the house is besieged. Tell the poor women I am doing it to help them." In response, Baldock organised a demonstration of about fifty women outside Mrs Montefiore's barricaded house in Hammersmith.

Later that year Baldock joined Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Nellie Martel, Helen Fraser, Adela Pankhurst and Flora Drummond as WSPU full-time organizers. Baldock now began to tour the country. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence "sent her a postal order for 30 shillings to cover her expenses while holding meetings in Long Eaton in Derbyshire."

Minnie Baldock was arrested during a demonstration outside the House of Commons in February 1908. She was sentenced to a month in Holloway Prison. The historian, June Purvis, has pointed out: "Her anxieties about her small son, left at home with his father, were somewhat alleviated by the knowledge that union members outside would offer help." For example, Maud Arncliffe Sennett sent a parcel of toys for her two boys.

In February 1909 Baldock worked alongside Annie Kenney, Clara Codd, Marie Naylor, Marie Naylor, Vera Holme and Elsie Howey in the West of England campaign. During this period she visited Eagle House near Batheaston, the home of fellow WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt. Her father, Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". In April 1910, Colonel Blathwayt sent her a hamper of plants, to brighten her East-End garden.

Minnie Baldock continued to work for the WSPU until July 1911 when she became seriously ill and was operated on for cancer by Dr Louisa Aldrich-Blake at the New Hospital for Women. She was visited in hospital by Christabel Pankhurst and Mabel Tuke wrote to her pointing out: "I am sure we can fix up a country visit for you when you come out of hospital with some kind member of the WSPU." However, when she left hospital she went to stay with Minnie Turner in Brighton.

Baldock never returned to work for the WSPU. This might have been because she disapproved of the WSPU arson campaign because she continued to be a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage. She was also in contact with Edith How-Martyn of the Women's Freedom League. In January 1913, Minnie moved to Southampton with her husband.

Minnie Baldock, who during her later years, lived at 73 Lake Road, Hamworthy, near Poole, died in 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) June Purvis, Force-feeding of Hunger-striking Suffragettes (26th April 1996)

From 1905 until the outbreak of the first world war, about 1,000 "suffragettes", as they became known, were sent to prison where, from 1909, many used the hunger strike as a political tool. Rather than concede to their demands, however, the government responded with forcible feeding. Under the notorious "Cat and Mouse" Act, rushed through parliament in April 1913, the vicious circle of hunger striking and forcible feeding became even more of an ordeal since prisoners who had damaged their health through their own conduct could be released into the community and then, once fit, rearrested to continue their sentence.

An in-depth study of prison life reveals a rather different picture from that presented so far. If we read the letters, diaries and autobiographies written by the prisoners themselves, we find many of the assumptions made by historians must be challenged.

The statement that WSPU prisoners were single rather than married women is not borne out by the evidence, although it is difficult to quantify the number of married women since some registered in fictitious or maiden names, often to avoid embarrassing their husbands. For wives and mothers, especially those with small children, the sexual politics of home, prison life and political activity intermeshed in myriad ways. Minnie Baldock, a WSPU organiser and wife of a fitter in Canning Town, was sentenced to one month's imprisonment in February 1908. Her anxieties about her small son, left at home with his father, were somewhat alleviated by the knowledge that union members outside would offer help. The wealthy Mrs. Maud Arncliffe Sennett, for example, sent the child some presents, much to his delight. "Thank you very much for the toys you sent me, " wrote the young Jack. "I am proud of my mother. I will be glad when she comes out of prison. But I now (sic) she is there for a good cause. I am saving up all farthings to put in that money box you was kind enough to send me."

It is commonly assumed too by historians that the suffragettes were middle class, educated and well-to-do women. Obviously, working-class women would have less time and money to give to "The Cause" than their wealthier sisters, but a number of poor women served prison sentences. Indeed, even by 1912, when there was a marked decline in new recruits to the WSPU, Ethel Smyth, the composer, found in Holloway jail more than 100 women "rich and poor I young professional women I countless poor women of the working class, nurses, typists, shop girls, and the like". These working-class women would have to rub shoulders with their more elevated sisters, such as Miss Janie Allan, a millionairess of the Allan Line and Lord Kitchener's niece Miss Parker.