Charlotte Despard

Charlotte French, the daughter of William French, a naval commander from Ireland, was born in Ripple, Kent, in 1844. By the age of ten her father had died and her mother was committed to an insane asylum and she was sent to London to live with relatives.

She had a conventional education. Later she was to recall: "I asked my governess why God had made slaves, and I was promptly sent to bed. Oh, how I hated the nurses and governesses, and I stood at the gates of my home and envied the little village children. They were free. They had liberty… The village children could run about as they liked and did not seem to be troubled by those superior persons, nurses and governesses. I went to the nearest railway station and tried to buy a ticket. Needless to say, I was stopped, but I had gone so far that I could not return that night, and I spent it alone at a station inn. After that, lest I should infect my sisters with my spirit of insubordination, I was kept in solitary confinement for three or four days, and then sent away to school."

For several years she toured the continent with her unmarried sisters. Charlotte met Maximilian Carden Despard, an Anglo-Irish businessman who had made a fortune in the Far East. The couple married on 20th December 1870. With her husband's encouragement, she published her first novel, Chaste as Ice, Pure as Snow in 1874. During the next sixteen years Charlotte wrote ten novels. Most of these novels were romantic love stories but A Voice from the Dim Millions dealt with the problems of a poor young factory worker. Charlotte was unable to find a publisher for this novel.

When her husband died in 1890, Charlotte decided to dedicate the rest of her life to helping the poor. She left her luxurious house in Esher and moved to Wandsworth to live with the people she intended to assist. According to her biographer, Margaret Mulvihill: "There she funded and staffed a health clinic, as well as organizing youth and working men's clubs, and a soup kitchen for the local unemployed. During the week she lived above one of her welfare shops and her identification with the local community was sealed by her conversion to Catholicism. At the end of 1894 she was elected as a guardian for the Vauxhall board of the Lambeth poor-law union. She proved herself a brilliant committee woman, bringing a rare combination of informed compassion, practical experience, and military efficiency to the board's deliberations."

In 1894 Despard was elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth. Charlotte became friends with George Lansbury and for the next few years became involved in the campaign to reform the Poor Law system. Charlotte Despard joined the Social Democratic Federation and later the Independent Labour Party. Despard also got to know Margaret Bondfield, the trade union leader and Keir Hardie, the new leader of the Labour Party.

Despard became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). However, in 1906, frustrated by the NUWSS lack of success, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic pointed out, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.”

Despard later recalled: "I had sought and found comradeship of some sort with men. I had marched with great processions of the unemployed. I had stood on the platforms of Labour men and Socialists. I had tried to stir up the people to a sense of shame about the misery of their homes, and the degradation of their women and children. I had listened with sympathy to fiery denunciations of Governments and the Capitalist systems to which they belong. Amongst all these experiences, I had not found what I met on the threshold of this young, vigorous Union of Hearts."

On 23rd October, 1906, Charlotte Despard was arrested with Mary Gawthorpe during a protest meeting at the House of Commons. As Sylvia Pankhurst later explained: "Mary Gawthorpe mounted one of the settees close to the statue of Sir Stafford Northcote and began to address the crowd of visitors who were waiting to interview various Members of Parliament. The other women closed up around her, but in the twinkling of an eye dozens of policemen sprang forward, tore the tiny creature from her post and swiftly rushed her out of the Lobby. Instantly Mrs. Despard stepped into the breach; but she also was roughly dragged away."

In 1907 she was imprisoned twice in Holloway Prison. However, like other leading members of the WSPU she began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy womenwere having too much influence over the organisation.

Nellie Martel, Emmeline Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard.

In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference. As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence pointed out: "She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people. Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to democracy, and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own."

As a result of this speech, Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

In a speech in 1910 Despard argued: "Fundamentally all social and political questions are economic. With equal wages, the male worker would no longer fear that his female colleague might put him out of a job, and 'men and women will unite to effect a complete transformation to the industrial environment… A woman needs economic independence to live as an equal with her husband. It is indeed deplorable that the work of the wife and mother is not rewarded. I hope that the time will come when it is illegal for this strenuous form of industry to be unremunerated."

Despard spent a great deal of time in Ireland and in 1908 she joined with Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Margaret Cousins to form the Irish Women's Franchise League. In 1909 Despard met Gandhi and was influenced by his theory of "passive resistance". As the leading figure of the WFL. Despard urged members not to pay taxes and to boycott the 1911 Census. Despard financially supported the locked-out workers during the labour dispute in Dublin and also helped establish the Irish Workers' College in the city.

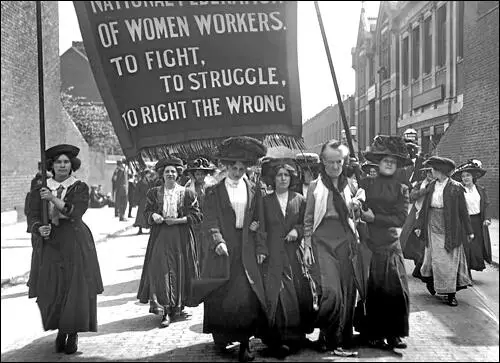

Workers through Bermondsey in South London (16th May 1911)

The Women's Freedom League grew rapidly, and soon had sixty branches throughout Britain with an overall membership of about 4,000 people. The WFL also established its own newspaper, The Vote. Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard were both talented writers and were the main people responsible for producing the newspaper. It was used to inform the public of WFL campaigns such as the refusal to pay taxes and to fill in the 1911 Census forms. Another contributor was one of Britain's leading writers, Cicely Hamilton.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Despard, like most members of the Women's Freedom League, was a pacifist, and so during the First World War she refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. Ironically, her brother, General John French, was Chief of Staff of the British Army and commander of the British Expeditionary Force sent to Europe in August 1914. Her sister, Catherine Harley, was also a supporter of the war and served in the Scottish Women's Hospital in France.

Despard argued that the British government was not doing enough to bring an end to the war and supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Council for a negotiated peace. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Charlotte Despard became the Labour Party candidate in Battersea in the post-war election. However, in the euphoria of Britain's victory, Despard's anti-war views were very unpopular and like all the other pacifist candidates, who stood in the election, she was defeated.

Despard's biographer, Margaret Mulvihill, has argued: "Among the suffragette leaders she had stood out as a supporter of Irish home rule, and when that movement gave way to the struggle for complete independence she became an active supporter of the British solidarity organization the Irish Self Determination League. Her sympathy for the Irish republican movement brought her into direct conflict with her brother, who in 1918 had been sworn in as lord lieutenant of Ireland. While he set about crushing the rebels, his sister was supporting them."

In 1920 Despard toured Ireland as a member of the Labour Party Commission of Inquiry. Together with Maud Gonne, she collected first-hand evidence of army and police atrocities in Cork and Kerry. The two women also formed the Women's Prisoners' Defence League to support republican prisoners. In the 1920s Despard became involved in the Sinn Fein campaign for a united Ireland.

In 1930 Despard and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington made a tour of the Soviet Union. Impressed with what she saw she joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and became secretary of the Friends of Soviet Russia organization.

Charlotte Despard died on 10th November 1939, after a fall in her new house near Belfast.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlotte Despard was born in Ripple in Kent in 1836. Her parents employed a governess to educate Charlotte. An account of these experiences was written in a brief, unpublished memoir.

I asked my governess why God had made slaves, and I was promptly sent to bed. Oh, how I hated the nurses and governesses, and I stood at the gates of my home and envied the little village children. They were free. They had liberty… The village children could run about as they liked and did not seem to be troubled by those superior persons, nurses and governesses. I went to the nearest railway station and tried to buy a ticket. Needless to say, I was stopped, but I had gone so far that I could not return that night, and I spent it alone at a station inn. After that, lest I should infect my sisters with my spirit of insubordination, I was kept in solitary confinement for three or four days, and then sent away to school.

(2) Charlotte Despard did not enjoy her experiences at boarding-school in the 1850s.

I was continually seeking to find expression for the force that was in me, trying to learn, asking to serve with my life in my hand ready to offer, and no one wanting it. I must not, I was told, pursue certain studies - they were for boys - I must not be so downright, it was unladylike. Heaven had decreed that I should be a woman and (it would be sometimes be added) a privileged woman. I must prove my gratitude by gentleness, obedience and submission.

(3) Charlotte Despard wrote about her feelings as a young woman in the 1850s in a brief, unpublished memoir.

It was a strange time, unsatisfactory, full of ungratified aspirations. I longed ardently to be of some use in the world, but as we were girls with a little money and born into a particular social position, it was not thought necessary that we should do anything but amuse ourselves until the time and the opportunity of marriage came along. "Better any marriage at all than none", a foolish old aunt used to say.

The woman of the well-to-do classes was made to understand early that the only door open to a life at once easy and respectable was that of marriage. Therefore she had to depend upon her good looks, according to the ideals of the men of her day, her charm, her little drawing-room arts.

(4) In the 1880s Charlotte Despard wrote an unpublished novel on the life of a factory girl called A Voice From the Dim Millions. The novel deals with the subject of working class poverty.

They call our deaths by many names - it is said to be consumption or heart-complaint or low-fever that is responsible… and people make it their boast that no one need die of starvation in England. But I should like to ask the doctors what is the cause of the consumption, the low-fever? In nine cases out of ten it is want - want that presses upon us day after day, year after year…. Two meals a day - sometimes only one - dry bread and tea, tea and dry bread… a straw mattress and bare boards at night with a thin sheet for covering. Stitch, stitch, for thirteen, fourteen, sixteen hours out of twenty-four. Headache, heartache, sickness, rheumatism, but no rest, for a day without earnings means the rent unpaid and the children crying for food. Is it a wonder that it kills?

(5) Although a elected Poor Law Guardian, Charlotte Despard, was totally opposed to the workhouse system and argued for outdoor relief for the poor. In a speech she made in 1897, she pointed out how women in particular suffered from the workhouse system.

My sister women, those struggling with social problems, and those who slave all their lives long for a community - shop, factory and domestic slaves, earning barely a subsistence, and thrown aside to death or the parish when they are no longer profitable - mothers, bearing and rearing children, seeing them go forth… and spending their own last years, lonely and unconsidered in the cheerless wards of the workhouse.

(6) Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement (1931)

On October 23, 1906, Parliament reassembled for the autumn session. A large number of our women made their way to the House of Commons on that day, but the Government had again given orders that only twenty women at a time were to be allowed in the Lobby. All women of the working class were rigorously excluded. My mother and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence were among those who succeeded in gaining an entrance. They at once sent in for the Chief Liberal Whip and requested him to ask the Prime Minister, on their behalf, whether he proposed to do anything to enfranchise the women of the country during the session, either by including the registration of qualified women in the provisions of the Plural Voting Bill then before the House, or by any other means. The Liberal Whip soon returned with a refusal from the Government to hold out the faintest hope that the Vote would be given women at any time during their term of office.

On hearing this, Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence returned to their comrades and consulted with them. The women had received a direct rebuff, and they felt that they must now act in such a way as to prove that the Suffragettes would no longer quietly submit to this perpetual ignoring of their claims. They therefore decided to hold a meeting of protest, not outside in the street, but just there, in the Lobby of the House of Commons. Mary Gawthorpe mounted one of the settees close to the statue of Sir Stafford Northcote and began to address the crowd of visitors who were waiting to interview various Members of Parliament. The other women closed up around her, but in the twinkling of an eye dozens of policemen sprang forward, tore the tiny creature from her post and swiftly rushed her out of the Lobby. Instantly Mrs. Despard stepped into the breach; but she also was roughly dragged away. Then followed Mrs. Cobden-Sanderson and many others, but each in her turn was thrust outside and the order was given to clear the Lobby. Mrs. Pankhurst was thrown to the ground in the outer entrance hall and many of the women, thinking that she was seriously hurt, closed round her refusing to leave her side. Crowds were now collecting in the roadway, and the women who had been flung out of the House attempted to address them but were hurled away.

(7) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Part in a Changing World (1938)

The Women's Social and Political Union when it was first formed had adopted a constitution framed on the lines of that of the Labour Party, to which the Pankhursts and all the original members in Manchester belonged.

The first national conference of delegates was due to take place this month, but some months before this date differences of thought and opinion had begun to manifest themselves amongst some of the members. The Union had grown very rapidly since the foundation of the London headquarters in 1906, and to cope with its demands organiser after organiser had been added to the staff. They were appointed because of their great courage and eloquence, and their ability to control and dominate crowds.

As September approached, it became evident that some influential people who had been attracted by the movement wished to frame a constitution that would substitute the principle of democratic control for that of individual leadership. It seemed to them reasonable and right that, following the practice of other organisations, the W.S.P.U. branches should be accorded the power to criticise and, if they could secure a majority, to amend the policies and the programme of the movement.

But there was another aspect of this question, an aspect acutely realised at headquarters. Newcomers were pouring into the Union. Many of them were quite ill-informed as far as the realities of the political situation were concerned. Christabel, who possessed in a high degree a flair for the intricacies of a complex political situation, had conceived the militant campaign as a whole. In her mind it drew its justifications from the frustrations of fifty years. These frustrations, she maintained, were not due to natural causes, but were directly due to the extremely adroit tactics of successive Governments that had enabled them to avoid dealing with the question. If the suffrage movement was ever to rise from the grave where politicians had led it, tactics equally adroit needed to be employed. She never doubted that the tactics she had evolved would succeed in winning a cause which, as far as argument or reason was concerned, was intellectually won already. She dreaded all the old plausible evasions and she feared the ingrained interiority complex in the majority of women. Thus she could not trust her mental offspring to the mercies of politically untrained minds. Moreover, the very fact that militant action involved individual sacrifice imposed heavy responsibilities upon the leaders of the campaign. Individuals who were ready to make the sacrifice that militancy entailed had to be sustained by the assurance of complete unity within the ranks. I agreed with this view of the situation, although I felt that it would be a difficult one to sustain in the conference. The issue to be raised was that of "democracy." It was an irony that this question of principle should come up in a political union which was to win votes for women. It became evident that, young as the militant movement was, it had to meet a crisis the solution of which would influence its future history.

While these clouds had been slowly gathering at headquarters Mrs. Pankhurst was conducting a campaign of meetings in the north. She knew nothing of the difficulties of the position until she returned to London on the eve of the conference. I shall never forget the gesture with which she swept from the board all the "pros and the cons" which had caused us sleepless nights. ''I shall tear up the constitution," she declared. This intrepid woman when apparently hemmed in by difficulties always cut her way through them.

The next day at the conference she asserted her position as founder of the Union, declared that she and her daughter had counted the cost of militancy, and were prepared to take the whole responsibility for it, and that they refused to be interfered with by any kind of constitution. She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people.

Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to "democracy," and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own.

Thereupon Mrs. Despard, Mrs. How-Martyn and Miss Billington and their followers formed a separate organisation, the Women's Freedom League. The severance was always referred to as "The Split."

(8) In 1907 Teresa Billington-Greig, Charlotte Despard and Elizabeth How-Martin made attempts to make the Women's Political and Social Union more democratic. When Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst responded by cancelling the proposed meeting to discuss the constitution, about seventy women left the WSPU and formed the Women's Freedom League. Teresa Billington Greig described her feelings about this conflict in her book The Militant Suffrage Movement.

In September, about a month before the date arranged for the gathering, Mrs Pankhurst, ignoring the Honorary Secretary, called a Committee meeting, declared the Conference annulled, the Constitution cancelled, and the rights of the members abolished, and proclaimed herself as sole dictator of the movement. She appointed herself secretary, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence treasurer, and Miss Christabel Pankhurst organizing secretary. She chose for herself a committee consisting of paid organisers and two or three women who were willing to lend their names to this purpose.

The clumsy declaration of autocracy broke the spell of many who would willingly have voted away their rights. Those who stuck to the Constitution formed the Women's Freedom League… This reversion to autocracy, this denial of suffrage in their own society to women seeking suffrage in the State, brought to a sudden close to this stage in the progress of militancy.

(9) In August 1909, Selina Cooper invited Charlotte Despard to speak to the Nelson Suffrage Society. Her speech was reported in the Colne and Nelson Times.

The suffragettes tried to present a petition… We simply went to the House of Commons in February last to assert our citizens' rights. We did not obstruct anybody, but the police obstructed us. I was given a month's imprisonment… We went again and again and we were not arrested, which shows we have gained some ground.