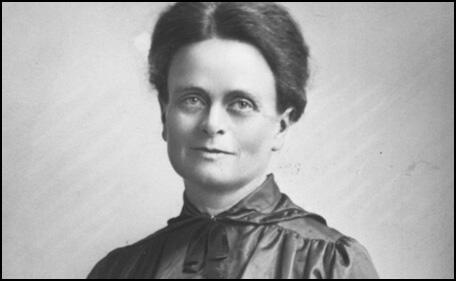

Elsie Inglis

Elsie Inglis, the second daughter of John Inglis (1820–1894), who worked for the East India Company, was born at Naini Tal, in India, on 16th August 1864. When her father retired from his job in 1878 the Inglis family returned to Scotland and settled in Edinburgh.

In 1878 Elsie began her education at the Edinburgh Institution for the Education of Young Ladies and at eighteen she went to a finishing school in Paris for a year.

Elsie Inglis lived a life of leisure until Sophia Jex-Blake opened the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women in 1886. With the support of her father, she began to train as a doctor. When Dr. Jex-Blake, dismissed two students for what Inglis considered to be a trivial offence, she obtained funds from her father and some of his wealthy friends, and established a rival medical school, the Scottish Association for the Medical Education for Women. Subsequently she studied for eighteen months at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. After completing her training she went to work for the New Hospital for Women, opened by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in 1890.

Elsie Inglis supported women's suffrage and had joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage while a student in Edinburgh. In 1892 she became more active in the campaign and agreed to the suggestion made by Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy to make speeches on women's medical education. She also joined the National Union of Suffrage Societies during this period.

In 1894 Inglis returned to Edinburgh and set up in practice with Dr. Jessie MacGregor, who had been a fellow student at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, and in 1898 opened a hall of resistance for women medical students. The following year Inglis was appointed lecturer in gynaecology at the Medical College for Women. She also opened a small hospital for women in George Square.

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "In addition to her medical work, from 1900 she was a very active suffrage campaigner in Scotland, speaking at up to four meetings a week, travelling the length and breadth of the country.... From 1909 Elsie Inglis, who was already honorary secretary of the Edinburgh National Suffrage Society, became secretary of the newly-formed Federation of Scottish Suffrage Societies."

It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Inglis was a lesbian and lived for many years with Flora Murray, who later had a romantic relationship with Louisa Garrett Anderson.

Inglis was a strong supporter of the National Union of Suffrage Societies strategy to obtain the vote. She joined with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy in signing the letter published in Votes for Women, on 26th July 1912 that protested against the arson campaign that had been unleashed by the Women Social & Political Union.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Inglis applied to Louisa Garrett Anderson for a place in the Women's Hospital Corps, but was told that they already had enough volunteers. Inglis now suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front. However, the War Office, rebuffed with the words, "My good lady, go home and sit still." Inglis now took the idea to the Scottish Federation of Women's Suffrage Societies, which agreed to form a hospitals committee. The Common Cause, the journal of the National Union of Suffrage Societies, also published a plea for funds and she was able to establish the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH).

As her biographer, Leah Leneman, has pointed out: "The War Office may have spurned the idea of all-women medical units, but other allies were desperate for help, and both the French and the Serbs accepted the offer. The first unit left for France in November 1914 and a second unit went to Serbia in January 1915. Inglis was torn between her desire to oversee the fund-raising and organizational side of the SWH and her desire to serve in the field, but in mid-April the chief medical officer of the first Serbian unit fell ill, and Inglis went out to replace her. During the summer she set up two further hospital units."

By 1915 the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit had established an Auxiliary Hospital with 200 beds in the 13th century Royaumont Abbey. Her team included Evelina Haverfield, Ishobel Ross and Cicely Hamilton. In April 1915 Elsie Inglis took a women's medical unit to Serbia. During an Austrian offensive in the summer of 1915, Inglis was captured but eventually, with the help of American diplomats, the British authorities were able to negotiate the release of Inglis and her medical staff.

During the First World War Inglis arranged fourteen medical units to serve in France, Serbia, Corsica, Salonika, Romania, Russia and Malta. In August 1916, the London Suffrage Society financed Inglis and eighty women to support Serbian soldiers fighting for the allies. One government official who saw the doctors and nurses working in Russia remarked that: "No wonder England is a great country if the women are like that."

Ishobel Ross recalls visiting the Balkan Front with Ingles in February 1917: "Mrs. Ingles and I went up behind the camp and through the trenches. It was so quiet with just the sound of the wind whistling through the tangles of wire. What a terrible sight it was to see the bodies half buried and all the place strewn with bullets, letter cases, gas masks, empty shells and daggers. We came across a stretch of field telephone too. It took us ages to break up the earth with our spades as the ground was so hard, but we buried as many bodies as we could. We shall have to come back to bury more as it is very tiring work."

In March 1917 Inglis had a disagreement with Evelina Haverfield. She later wrote: "I hope the Committee will realize that though Mrs. Haverfield and I differed over the plans for the future, there isn't a particle of ill-feeling between us. Mrs. Haverfield is as generous and open-minded and as ready to face facts as she always was. All we either of us care about is the success of the unit - and our ideas differ... The Committee must decide between us! - Anyhow they may be thoroughly proud of the work the Transport has accomplished."

Florence Farmborough was one of those who met her while she was serving in Podgaytsy. "There is an English hospital in Podgaytsy, run by a group of English nurses, under the leadership of an English lady-doctor (Dr. Elsie Inglis). I was very glad to chat with them in my mother-tongue and above all to learn the latest news of the allied front in France. They are very nice women, those English and Scottish nurses. They all have several years of training behind them. I feel distinctly raw in comparison, knowing that a mere six-months' course as a VAD in a military hospital would, in England, never have been considered sufficient to graduate to a Front Line Red Cross Unit."

Elsie Inglis was taken ill while in Russia and was forced to travel back to Britain. Inglis, who was suffering from cancer, arrived at Newcastle Upon Tyne on 25th November, 1917, but local doctors were unable to save her and she died the following day. Arthur Balfour, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs commented on her death: "Elsie Inglis was a wonderful compound of enthusiasm, strength of purpose and kindliness. In the history of this World War, alike by what she did and by the heroism, driving power and the simplicity by which she did it, Elsie Inglis has earned an everlasting place of honour."

Primary Sources

(1) Elizabeth Crawford, The Suffragette Movement (1999)

Elsie Inglis had signed the Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage in 1889, but it was when she moved to London to take up position as house-surgeon in 1892 that she became an active suffrage worker... In addition to her medical work, from 1900 she was a very active suffrage campaigner in Scotland, speaking at up to four meetings a week, travelling the length and breadth of the country.... From 1909 Elsie Inglis, who was already honorary secretary of the Edinburgh National Suffrage Society, became secretary of the newly-formed Federation of Scottish Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

(2) Dr. I. Hutton described the state of the patients that the women nursed at the Royaumont Abbey Hospital.

It was bitterly cold. The patients who were not in a raging fever shivered and tried vainly to adjust their tattered uniforms to gain a little warmth. Their clothing crawled with maggots and bugs and their bodies with lice. Dying men lay huddled so closely together on the floor that they touched each other. Others sat up gasping and blue in the throes of pneumonia. Blood and pus oozed from the wounds. A few of the patients feebly extended their hands but most of them were too ill to care what happened. Seventy-odd soldiers, in the last stages of dysentery lay crouched along the walls, emaciated, dying. They crawled outside from time to time. There were no sanitary arrangements and the grass plot was foul.

(3) Government official commenting on the Women's Medical Unit working at Costanza (1917)

It is extraordinary how these women endure hardships; they refuse help and carry the wounded themselves. They work like navvies. No wonder England is a great country if the women are like that.

(4) In May 1917 Florence Farmborough met Dr. Elsie Inglis and her nurses at a hospital in Podgaytsy.

There is an English hospital in Podgaytsy, run by a group of English nurses, under the leadership of an English lady-doctor (Dr. Elsie Inglis). I was very glad to chat with them in my mother-tongue and above all to learn the latest news of the allied front in France.

They are very nice women, those English and Scottish nurses. They all have several years of training behind them. I feel distinctly raw in comparison, knowing that a mere six-months' course as a VAD in a military hospital would, in England, never have been considered sufficient to graduate to a Front Line Red Cross Unit. They could not believe that I had experienced all those nightmare months of the Great Retreat of 1915, as well as the Offensive of 1916. "You don't look strong enough to have gone through all that, said the lady-doctor, "and too young," she added, "I don't think I should have chosen you for my team." I secretly rejoiced that I had my training in Russia!"

I was surprised and not a little perturbed when I saw that tiny bags, containing pure salt, are sometimes deposited into the open wound and bandaged tightly into place. It is probably a new method; I wonder if it has been tried out on the Allied Front.

These bags of salt - small though they are - must inflict excruciating pain; no wonder the soldiers kick and yell; the salt must burn fiercely into the lacerated flesh. It is certainly a purifier, but surely a very harsh one!

At an operation, performed by the lady-doctor, at which I was called upon to help, the man had a large open wound in his left thigh. All went well until two tiny bags of salt was placed within it, and then the uproar began. I thought the man's cries would lift the roof off; even the lady doctor looked discomforted. "Silly fellow," she ejaculated. "It's only a momentary pain. Foolish fellow! He doesn't know what is good for him."

(5) In her diary Ishobel Ross, a member of the Scottish Women's Hospital Unitrecorded visiting the Balkan Front with Elsie Inglis (15th February, 1917)

Mrs. Ingles and I went up behind the camp and through the trenches. It was so quiet with just the sound of the wind whistling through the tangles of wire. What a terrible sight it was to see the bodies half buried and all the place strewn with bullets, letter cases, gas masks, empty shells and daggers. We came across a stretch of field telephone too. It took us ages to break up the earth with our spades as the ground was so hard, but we buried as many bodies as we could. We shall have to come back to bury more as it is very tiring work.

(6) Arthur Balfour, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (1917)

Elsie Inglis was a wonderful compound of enthusiasm, strength of purpose and kindliness. In the history of this World War, alike by what she did and by the heroism, driving power and the simplicity by which she did it, Elsie Inglis has earned an everlasting place of honour.

(7) Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain (2007)

Other wartime occupations actively encouraged younger unmarried women recruits and a number of women who made a significant contribution to the war effort through their work were in relationships with other women. It is difficult to interpret the precise nature of women's close friendships in the absence of explicit evidence as to how the women themselves viewed them, however. Dr Elsie Inglis, founder of the SWH, had lived with Dr Flora Murray for a number of years in Edinburgh, and Drs Louisa Martindale and Louisa Aldrich-Blake also lived with women. Emily Hamer argues that Evelina Haverfield, founder of a number of women's Voluntary organisations, including the Women's Emergency Corps and the Women's Volunteer Reserves, was a lesbian and lover of the former suffragette Vera 'Jack' Holme. The two women worked closelv with Dr Elsie Inglis in Serbia during the war, and when Haverfield died in 1920, Holme staved in Serbia working as an ambulance and relief lorry driver.