Gladys Evans

Gladys Evans, the third of nine children born to Amy Martha Gigney and Arthur Henry Evans in Hackney on 15th December 1877. Her father was a stockbroker who later became a financial journalist on The Bullionist (a daily financial newspaper established in 1866) that had been owned by his father David Morier Evans. In 1889 he purchased Vanity Fair from Thomas Gibson Bowles for the sum of £20,000. (1)

Evans joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908. Evans started work at Selfridges when it opened in March 1909, but resigned in 1910 to run a WSPU shop. The family emigrated to Canada in 1911, but Gladys returned in March, 1912, when she heard about the Conspiracy Trial of Emmeline Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and offered her services to the WSPU. (2) According to Elizabeth Crawford Evans became a drummer in the WSPU Drum and Fife Band. (3)

On 16th July, 1912, Gladys Evans and Jennie Baines caught a boat from Holyhead to Dublin and took lodgings in Lower Mount Street. Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper arrived two days later. They were in the city because Herbert Asquith was to give a speech on Home Rule to 4,000 supporters. On the 18th July, Leigh saw Asquith travelling in an open carriage with John Redmond and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. She hurled a hatchet at Asquith, but missed him and hit Redmond on his ear. (4)

According to John O'Brien, the Chief Marshall: "When abreast of Prince's Street he saw an article flung from the opposite side. He ran round by the horses' head and saw the accused (Mary Leigh) holding on to one of the rails of the carriage. He saw the accused throw the article. He pulled her away from the carriage, when she counteracted him, and started to poke him and tear at him, and struck him a couple of blows in the face." (5)

Leigh was able to escape and that night, along with Gladys Evans attended a production of the Theatre Royal. As the audience was leaving Joseph Keoth noticed a woman (Evans) throwing a burning rag soaked in paraffin into the projection box at the back of the stalls and running away as if she "expected some explosion". Evans then chucked a handbag filled with gunpowder and matches into a box near the stage. Leigh also threw a burning chair into the orchestra pit. "Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which, with bottles of petrol and benzine, were afterwards found lying about." (6)

Evans was arrested at the scene and Leigh at her lodgings the next morning. Jennie Baines and Mabel Capper were also taken into custody. The four women were charged with having "unlawfully conspired with other persons, known, and unknown, to inflict grievous bodily harm and wilful and malicious damage upon property, and to cause an explosion in the Theatre Royal of a nature likely to endanger life or to cause serious injury to property; and that in pursuance of this object they attempted to set fire to the theatre." (7)

Tim Healy represented Evans at her trial. Votes for Women reported: "In his fine and impassioned speech for the defence of Miss Gladys Evans, he (Tim Healey) was rankly contemptuous of the trifling quantity of the damage to a couple of curtains, a carpet, and two chairs, only in comparison with the vaster outrages committed by the forerunners of the present-day electors, but with a greater and still more powerful emphasis, in comparison with the daily and hourly destruction of women's and children's lives in the cities of our civilisation." (8)

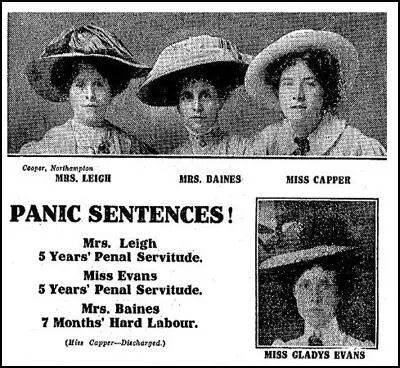

Mary Leigh told them that if they sent her to prison she might not survive the sentence. Mary warned that if convicted she would fight: "she would put her back against the wall, and nothing, not even the whole army of the Government and officials, would bring her to submission. The jury returned guilty verdicts on Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans. Both women were sent to prison for five years because "no more terrible catastrophe could occur in a city than a conflagration at a theatre". Jennie Baines was sentenced to seven months with hard labour, and Mabel Capper was acquitted for lack of evidence." (9)

The women went on hunger-strike. On 7th August Mary Leigh weighed ninety-five pounds, and Gladys Evans a hundred and fourteen pounds. Before they were force-fed for the first time, their weight had fallen to ninety and ninety-six pounds respectively. After a week Mary's weight had dropped to eighty-six pounds and Gladys had lost only half a pound. Despite having been fed three times a day, Mary had lost ten pounds in eighteen days and the authorities feared that she would die. (10)

Leigh was released on licence on 20th September 1912 weighing five stones and four pounds.: "When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order. The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today. Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation." (11)

As soon as she recovered she began a campaign to get Gladys Evans released: "Mrs Mary Leigh, the suffragette who was released from Mountjoy Convict Prison last week after a hunger strike, sent a letter to a suffragette meeting in Dublin on Sunday stating that if her fellow-prisoner, Miss Gladys Evans, who had been sentenced to five years's penal servitude, is not released during the next few days she (Mrs Leigh) would lead a march on Mountjoy Prison, and the issue would only be decided by victory or death." (12)

The health of Gladys Evans began to give the authorities concern. Her heartbeat became irregular and she showed signs of "great nervous tension and general breakdown." She also began to resist the feeding process. It was reported she "violently resisted all efforts that were made to feed her and struggled very much". Five wardresses were needed to overcome her, and she had to be strapped by the ankles and wrists into the feeding chair. Evans was released on licence on 3rd October on medical grounds, after fifty-eight days of hunger-striking and being fed by stomach tube eighty-eight times. (13)

Votes for Women reported: " To the great joy of the comrades of the Women's Social and Political Union, Miss Gladys Evans has won her way to freedom through the terrible suffering of the hunger strike. In a state of almost complete collapse, she was removed on medical advice, on Thursday last week to a private house… On the Monday before her release she barricaded her cell door, which was burst open. On Tuesday she managed to block the bathroom door, and when it was broken open took refuge in the filled bath fully clad. This she did to cause delay, and put off the moment of torture. On Wednesday she fought and struggled so that they were unable to feed her at all, and on Thursday her condition was such that the authorities decided they must release her." (14)

Newspapers complained that it was wrong that Gladys Evans had escaped her five years in prison sentence. A few weeks later she was arrested again. However, the magistrate refused to revoke her license and she was released: "The words of the magistrate are remarkable. It was difficult, he said, to carry out strictly the law in the case of people who were absolutely reckless of the consequences, for whom punishment had no terror, and penal servitude no shame. He could not entertain the idea of sending the prisoner back to penal servitude by revoking her license. The prisoner has brought more suffering on herself than the most merciless law could impose, and he thought the six days she had been on remand were sufficient punishment for no non-compliance with the law, possibly through a mistake. He therefore discharged her." (15)

Gladys Evans recuperated in Berne, Switzerland. However, along with Mary Leigh she was in the WSPU office at Lincoln's Inn House, when it was raided on 30th April 1913. According to one source 45 plain clothes policemen from scotland yard arrived in a fleet of taxis. At the some moment, a large contingent of uninformed officers, who had been hiding in a side street, emerged and the combined force stormed the building. Several people were arrested including Edwy Godwin Clayton, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Rachel Barrett (editor of the The Suffragette), Harriet Kerr (office manager), Beatrice Sanders (financial secretary), Geraldine Lennox (sub-editor) and Agnes Lake (business manager). However, Gladys Evans and Mary Leigh were released without charge. (16)

reverse: Mrs Mustard, Miss Clarke, Dr Elizabeth Knight, Gladys Evans, Miss Underwood, Miss Gibson,

Miss Hodge, Mrs Schofield Coats, Emma Sproson , Miss Head and Mrs Wheaton (c. 1914)

During the First World War she drove a lorry in France and worked as a chauffeur to a relief mission in Blerancourt Chateau, in Aisne near the Belgian Border. (17) According to her niece, Joan Skinner: "Anne Morgan paid for her to come to New York and take a Frances Fox Beautician's course. Worked in Long Island at a nursing home. In her sixties she developed what would now be called Alzheimers. She could not come back to the Skinners in Montreal because she was in the US illegally and my father got her a railway pass to Los Angeles where Ethel and eventually the Little Sisters of the Poor looked after her." (18)

Gladys Evans died in Los Angeles in 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (11th June, 2020)

Gladys Evans was born in Hackney , London, on 15th December 1877, the third of 9 children born to Amy Martha Gigney (born 1853 on the island of St Helena) and Arthur Henry Evans (born 8th October 1853, Bethnal Green. London - died 12th May 1891, Stoke Newington, London). When Gladys Evans was born, her father, Arthur Henry Evans was working as a "Stock Broker" (SOURCE: 1881 Census "Stock Broker", aged 28 - Gladys Evans is recorded as his 3 year old daughter). In the 1880s, Arthur Henry Evans was working as a financial journalist on The Bullionist (a daily financial newspaper established in 1866) that had been owned by his father David Morier Evans.

Arthur H. Evans' father David Morier Evans (1818-1874) is described in census returns and other sources as a " shorthand writer ", "author", "newspaper proprietor " and "Editor of 'The Bullionist' newspaper'. In the 1880s Arthur Henry Evans was employed as the editor of 'The Bullionist' and at the time of his death in May 1891, he was described as a " Newspaper Proprietor " [Source: Probate Calendar & Index of Wills, 1891].

In 1889, Arthur Henry Evans , who had been employed as the 'Financial Editor' of 'Vanity Fair ', purchased 'Vanity Fair' magazine from Thomas Gibson Bowles for the sum of £20,000. Arthur Henry Evans is recorded as the Proprietor of ' Vanity Fair '. (SOURCE: Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in Great Britain)

At the time of the 1891 Census, Arthur Henry Evans was residing at 'Elm Lawn', Woodberry Down, Stoke Newington, London. On the census return, 38-year-old Arthur Evans is recorded as a "Journalist, Author" . Gladys Evans is entered on the 1891 census return as Arthur Evans' 13 year old daughter. Arthur Henry Evans died on 12th May 1891, aged 38. In the probate record, Arthur Henry Evans of Elm Lawn, Woodbury (Woodberry) Down, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, is described as a " Newspaper Proprietor " and had a personal esate valued at £8,570.

(2) Votes for Women (9th August 1912)

Mr T. M. Healy, KC, appeared for all the prisoners except Mrs Leigh, who conducted her own case, and addressed the jury at considerable length on the woman's suffrage movement, pointing out that women had tried constitutional methods, which had failed, and contending that the case against her had not been proved. The judge referred to her as "a very remarkable lady of great talents" …

In his fine and impassioned speech for the defence of Miss Gladys Evans, he (Tim Healey) was rankly contemptuous of the trifling quantity of the damage to a couple of curtains, a carpet, and two chairs, only in comparison with the vaster outrages committed by the forerunners of the present-day electors, but with a greater and still more powerful emphasis, in comparison with the daily and hourly destruction of women's and children's lives in the cities of our civilisation.

Magnificent as was the plea of Mr Healy, the dramatic feature of the day was undoubtedly Mrs Leigh's defence of her case. Slight and frail in outward appearance, spontaneous and alert in manner, she seemed strangely out of place among the burly officials and dull routine of a court of justice. Her masterly cross-examination was so searching as seriously to baffle several witnesses and confuse their evidence on the point of identification, so that the jury found themselves unable to agree that she actually was one of the persons who fired the Theatre Royal. Her speech to the Court was a heroic effort. It was not rhetoric, nor careful arrangements of arguments and telling points, nor even eloquence, that moved the hearts so strongly of all who gazed upon her pleading countenance as she laboured to reiterate the long tale of injustice and evasion meted out to the women who asked for the removal of the disqualification of their sex, and the equally long tale of the steadily successful attainment by men of their political objects in England and Ireland by the sole means of agitation by violence. The pathos of her passionate determination to persevere in her efforts to the emancipation of her womanhood moved the judge himself and many other with deep emotion. Her courage was an amazement even to women who have felt most deeply the things we have at heart.

(3) Irish Independent (21 September 1912)

When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order.

The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today.

Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation.

(4) Derby Daily Telegraph (23 September 1912)

Mrs Mary Leigh, the suffragette who was released from Mountjoy Convict Prison last week after a hunger strike, sent a letter to a suffragette meeting in Dublin on Sunday stating that if her fellow-prisoner, Miss Gladys Evans, who had been sentenced to five years's penal servitude, is not released during the next few days she (Mrs Leigh) would lead a march on Mountjoy Prison, and the issue would only be decided by victory or death.

(5) Derby Advertiser and Journal (27 September 1912)

Mrs Mary Leigh, the Suffragette who, on August 8 last, was sentenced, along with Gladys Evans, to five years penal servitude on a charge of setting fire to the Theatre Royal, Dublin, was on Friday released from Mountjoy Prison, Dublin. She had been practising the hunger strike, and was so emaciated that she had to be lifted from the taxi-cab in an invalid chair at the private house to which she was taken.

(6) Votes for Women (11 October 1912)

To the great joy of the comrades of the Women's Social and Political Union, Miss Gladys Evans has won her way to freedom through the terrible suffering of the hunger strike. In a state of almost complete collapse, she was removed on medical advice, on Thursday last week to a private house…

On the Monday before her release she barricaded her cell door, which was burst open. On Tuesday she managed to block the bathroom door, and when it was broken open took refuge in the filled bath fully clad. This she did to cause delay, and put off the moment of torture. On Wednesday she fought and struggled so that they were unable to feed her at all, and on Thursday her condition was such that the authorities decided they must release her.

(7) Votes for Women (1 November 1912)

The dastardly attempt of the Government to make Miss Gladys Evans serve a further term of imprisonment has signally failed. The magistrate has refused to revoke her license, and she is therefore again at liberty. It is well, however, that the public should realise just what the Government proposed, because we are all aware that it is only public opinion that prevents them from proceeding to any lengths, however cowardly and dishonourably, in their dealings with women. Miss Evans was sentenced, it will be remembered, to five years' penal servitude; she refused to be treated as a common criminal, and adopted the hunger strike. After a long process of forcible feeding. In which she was reduced to the point of death, she was at last set at liberty. But the Government, following the suggestion of a anonymous letter writer to the Irish Times, instead of releasing her unconditionally, adopted the expedient of releasing her "on license". Miss Evans very naturally refused to comply with the degrading conditions of her license, and was arrested on Wednesday last week and sent to prison for a week under remand. We understand she adopted the hunger strike, and on her appearance in court was in a terribly weak condition. The words of the magistrate are remarkable. It was difficult, he said, to carry out strictly the law in the case of people who were absolutely reckless of the consequences, for whom punishment had no terror, and penal servitude no shame. He could not entertain the idea of sending the prisoner back to penal servitude by revoking her license. The prisoner has brought more suffering on herself than the most merciless law could impose, and he thought the six days she had been on remand were sufficient punishment for no non-compliance with the law, possibly through a mistake. He therefore discharged her.

(8) Elizabeth Crawford, Suffrage Stories (29 April, 2014)

Gladys Evans, the daughter of a man, now dead, who had owned the British weekly magazine Vanity Fair –a very influential ‘society' paper ( not to be confused with the Conde Naste magazine which in 1914 adopted the name). Gladys joined Selfridge's in 1908 in preparation for the opening of the new store and worked there for over a year before leaving to take over a WSPU shop. In 1911 she emigrated to Canada, where a sister had settled, but returned in March 1912 after learning of the arrests of Mrs Pankhurst and Mr and Mrs Pethick Lawrence.

Firmly back on the WSPU warpath, in July 1912 Gladys went over to Dublin where Asquith was on a formal visit and, with other suffragettes, Mary Leigh and Jennie Baines, set fire to a theatre – empty at the time – but the one in which Asquith was due to speak that evening. Gladys Evans was given a long prison sentence, went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed for 58 days.

There was a good deal of lobbying to get her and her companions given the status of political prisoners – which would have allowed them better conditions. One of those who wrote on Gladys' behalf was Selfridge's staff manager, Mr Best. and 253 of the store's employees signed a Memorial sent to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland pleading for a remission of Gladys Evans' sentence – see Votes for Women, 6 September 1912. Apparently, even Mr Selfridge himself was sympathetic, though reluctant to put pen to paper in Gladys' support because, as an American, he thought it might look as though he were trying to interfere in matters that didn't concern him. Gladys and Mary Leigh were eventually returned to England, where they promptly gave the police the slip and went on the run.

For most of her later life Gladys Evans lived in the US, dying at the age of 90 in Los Angeles. Evans' family history relates that Gladys gave all her suffragette papers to the New York Public Library. I have not, however, been able to find a listing for them. That might be a research project for an interested New Yorker.

Selfridge's suffrage sympathies may have stood the store in good stead when the WSPU went on its window-smashing campaigns in November 1911 and March 1912. Many department stores- even those which, like Swan and Edgar, were regular advertisers in Votes for Women – were targeted. But Selfridge's windows – 21 in all, of which 12 contained the largest sheets of plate glass in the world – escaped unscathed.

(9) Joan Skinner, Gladys Evans: Suffragette (20 July, 2010)

Gladys Evans, suffragette. Born December 15 1877, died 1967, daughter of Arthur Henry Evans and Amy Martha Gigney.

She worked at Selfridge's in London for three years. She had emigrated to Canada in 1911 but returned to England in March of 1912 on learning of the trial of Mrs. Pankhurst and the Lawrences. She was imprisoned in Dublin Women's Gaol for trying to set fire to the Abbey Theatre in July 1912. She got out of prison on October 23rd 1912. While in prison she was on a hunger strike and was force fed for nine weeks. She could have married Hugh Mount Joy O'Connor, her lawyer, when he was on leave. Two suffragette women left her money. The organization sent her to Berne, Switzerland to recuperate from kidney damage caused by the forcible feeding. She drove a supply truck in WWI and then went as a chauffeur to a relief mission in Blerancourt Chateau, Aisne France near the Belgian Border. Anne Morgan paid for her to come to New York and take a Frances Fox Beautician's course. Worked in Long Island at a nursing home. In her sixties she developed what would now be called Alzheimers. She could not come back to the Skinners in Montreal because she was in the US illegally and "my father got her a railway pass to Los Angeles where Ethel and eventually the "Little Sisters of the Poor" looked after her."

She gave all her suffragette papers to the New York Public Library.