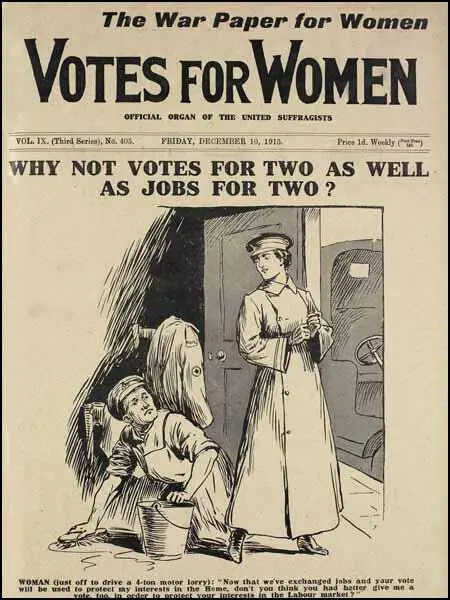

Votes for Women

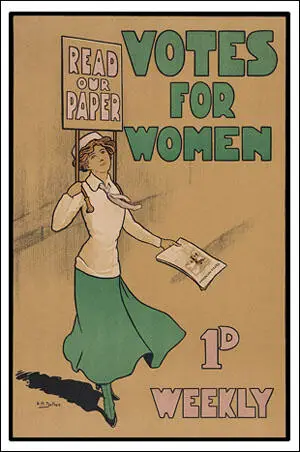

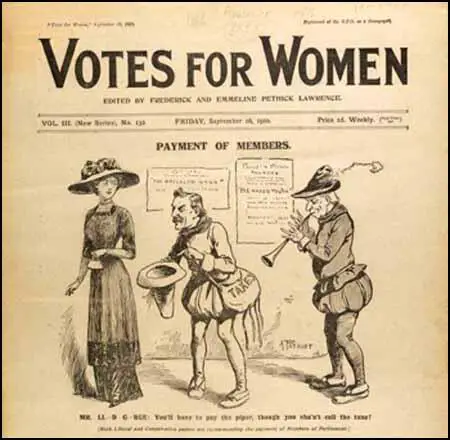

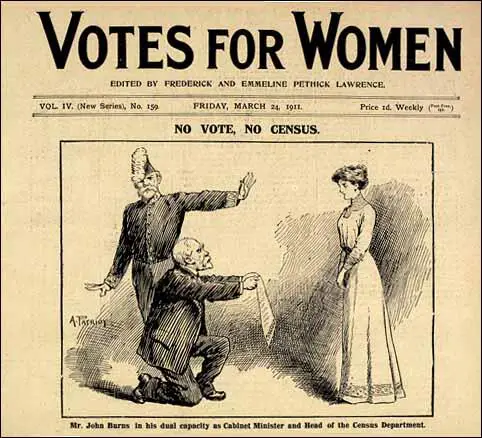

The Women Social & Political Union established its own newspaper, Votes for Women, in October 1907. Its first editors were the husband and wife team of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. The newspaper was printed by the St. Clement's Press. It was originally a monthly but after April 1908 it was published every week. At this time sales reached 5,000 copies a month. The newspaper was funded by the Pethick-Lawrences and all attempts to make a profit from the venture was abandoned in May, 1908 when it was decided to reduce the price from 3d to 1d.

In October 1909 the WSPU launched an aggressive advertising campaign for Votes for Women, permanent pitches were established in major cities to sell the newspaper. The Suffragette Bus, that toured the streets of London, also advertised the paper. By 1910 the circulation of the newspaper had increased to 30,000 a week.

Edith Craig was one of the women who sold Votes for Women: "I love it. But I'm always getting moved on. You see, I generally sell the paper outside the Eustace Miles Restaurant, and I offer it verbally to every soul that passes. If they refuse, I say something to them. Most of them reply, others come up, and we collect a little crowd until I'm told to let the people into the restaurant, and move on. Then I begin all over again."

On 5th March 1912, detectives arrived at the WSPU headquarters at Clement's Inn to arrest Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. It was the Pethick-Lawrences who edited and financed the WSPU's newspaper, Votes for Women. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "Frederick Pethick Lawrence believed that Evelyn Sharp was the one person with the requisite technical experience and political acumen to take over the paper as assistant editor - it was just twenty-four hours away from going to press - and this she agreed to do." Elizabeth Robins has argued that after Evelyn Sharp took charge, the newspaper had an editor of "distinguished ability and rare devotion."

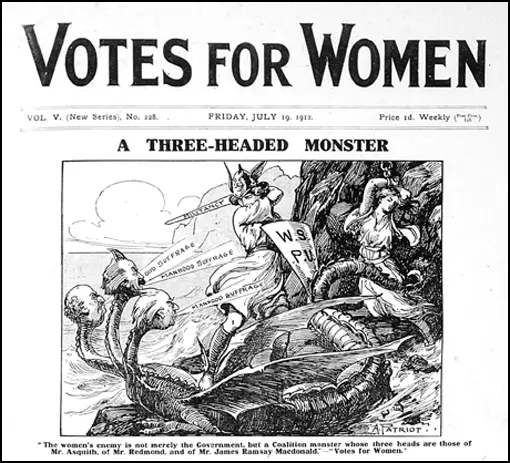

Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France but Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. On their release from prison, the Pethick-Lawrences began to speak openly about the possibility that this window-smashing campaign would lose support for the WSPU. At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline and Frederick about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

As a result of this expulsion, the WSPU lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, Suffragette. The Pethick-Lawrences continued to publish the newspaper until 1914 when it was handed over to the United Suffragists. However, they did not continue to fund the newspaper and in October 1915, because of financial constraints, became a monthly, rather than a weekly newspaper. As soon as the 1918 Qualification of Women Act was passed, Votes for Women, ceased publication.

Primary Sources

(1) Angela V. John, Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009)

The WSPU's official newspaper had first appeared in October 1907 as a monthly newspaper. It soon expanded and became a popular penny weekly. At its height between forty and fifty thousand copies were sold weekly though it was read by many more. Evelyn Sharp had contributed to the paper since its early days. Pethick-Lawrence commented how her articles "had a pungency all her own without a trace of malice."

Now she was the salaried editor with responsibility for the paper's production. Volunteers helped prepare the newspaper's layout as well as pack and despatch. Contributors were not paid. Evelyn was keen to get people who did not usually write for the paper, including authors, politicians and ordinary supporters, to offer something.

(2) Edith Craig, The Vote (12th March, 1910)

It was seeing Votes for Women sold in the street in an apologetic manner that made me feel that I wanted to do it quite differently, and I began joining societies right away. That was some time ago, you know, and our sellers don't apologise for their existence now...

I love it. But I'm always getting moved on. You see, I generally sell the paper outside the Eustace Miles Restaurant, and I offer it verbally to every soul that passes. If they refuse, I say something to them. Most of them reply, others come up, and we collect a little crowd until I'm told to let the people into the restaurant, and move on. Then I begin all over again.

(3) Elizabeth Robins, Votes for Women (December 1909)

The State keeps 22,483 children in workhouses. Here is a description of a Government nursery: "Often found under the charge of a person actually certified as of unsound mind, the bottles sour, the babies wet, cold and dirty. The Commission on the Care and Control of the Feebleminded draws attention to an episode in connection with one feeble-minded woman who was set to wash a baby; she did so in boiling water, and it died."

"We were shocked," continues the Report, "to discover that infants in the nursery of the establishments in London and other large towns seldom or never get into the open air. "We found the nursery frequently on the third or fourth story of a gigantic block often without balconies, whence the only means of access even to the workhouse yard was a flight of stone steps down which it was impossible to wheel a baby-carriage of any kind. There was no staff of nurses adequate to carrying fifty or sixty infants out for an airing. In some of these workhouses it was frankly admitted that these babies never left their own quarters (the stench was intolerable) and never got into the open air during the whole period of their residence in the workhouse nursery. In some workhouses 40% of the babies die within the year.

I doubt if there exists in print a better plea for the urgency of Woman's Suffrage that that embodied in this Report of the latest English Poor Law Commission… What it reveals is an incompetence and legalised cruelty in the treatment of the poor… that thousands of innocent children are shut up with tramps and prostitutes; that there are workhouses which have no separate sick ward for children, in spite of the ravages of measles, whooping-cough, etc.

Men have talked about these evils for seventy-five years. We see now that until the portion of the community standing closest to the problems presented by care of the old and broken, the young children and the afflicted, until women have a voice in mending the laws on this subject, the inadequacy of the laws will continue to be merely discussed.

(4) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

I was compensated for my second imprisonment by an extension of my interrupted holiday, gladly conceded by my chief, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, joint-editor with his wife of the journal Votes for Women. Before March, 1912, when the Government raided the W.S.P.U. headquarters and charged the leaders with illegal conspiracy, my feeling both for the Pankhursts and the Pethick Lawrences had been one of admiration and trust, but it had never occurred to me to allow a more personal note to creep into my relations with any of them. The crisis caused by the Government's action was followed by a series of events I need not record here, which impelled the Pethick Lawrences, with the unselfishness and sincerity that have always characterised their outlook upon life, to retire from the Union they had done so much to build up, rather than weaken the militant movement by splitting it into factions. I was already assistant-editor of their paper, Votes for Women, and my immediate decision to continue in that post and to work with them brought me into a more intimate connection which developed into a happy and lasting friendship.