Alfred Pearse

Alfred Pearse, the second eldest son of Loveday Colbron (1825-1895), the daughter of a "Stay Maker" and Joseph Salter Pearse (c. 1822-1896), was born in Paddington, London on 20th May 1855. His father, a former house decorator who became a celebrated "Decorative Artist". Alfred grew up in the Islington and Marylebone districts of London and was privately educated. Between the age of 15 and 19, he trained as a "Wood Draughtsman", drawing images and patterns on blocks of wood in preparation for printmaking. (1)

Alfred Pearse studied at the West London School of Art and in 1881 he married Mary Blanche Lockwood (1851-1929), a neice of the famous cartoonist John Tenniel. (2) This union produced 6 children: Denis Colbron Pearse (1883-1971), Gladys May Pearse (1884-1962), Lilian Gertrude Pearse (1885-1984), Dulcie Anette Pearse (1886-1968), Marjorie Beryl Pearse (1888-1978) and Nessie Deane Pearse (1892-1963). Alfred Pearse's son Denis Colbron Pearse (1883-1971), also became an artist and illustrator. (3)

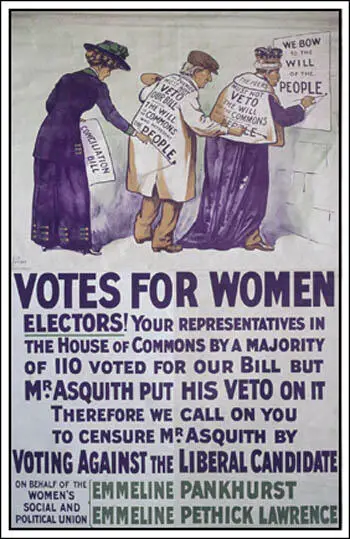

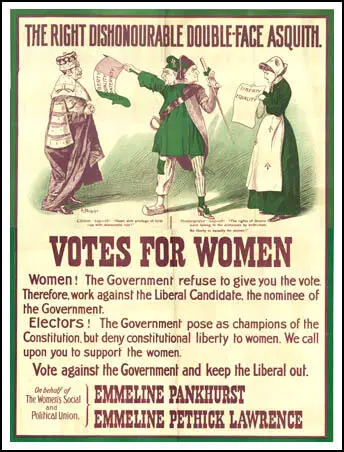

At the turn of the century, Alfred Pearse, now an established artist, was also regularly published in Punch Magazine, The Illustrated London News, the Boy's Own Paper, and the The Strand. (4) Pearse held progressive political opinions and was a member of Men's League For Women's Suffrage. During this period he became an associate of Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and his wife Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. (5)

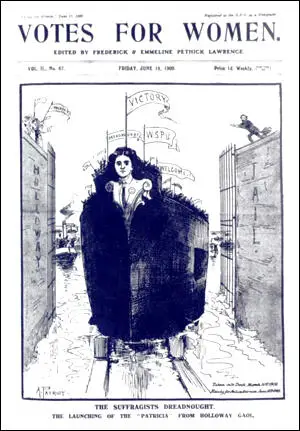

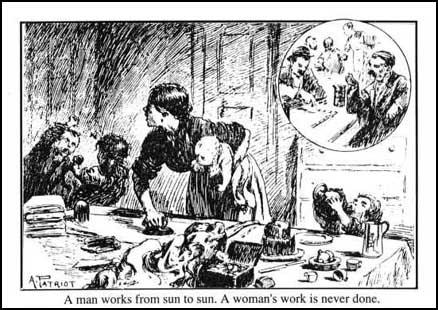

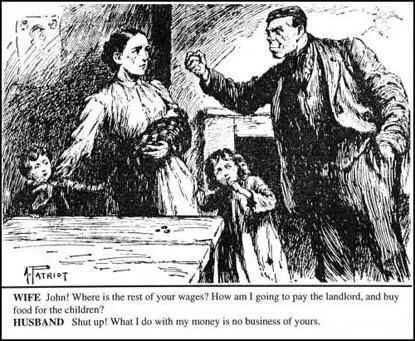

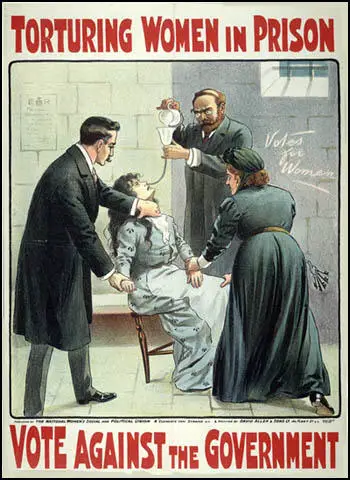

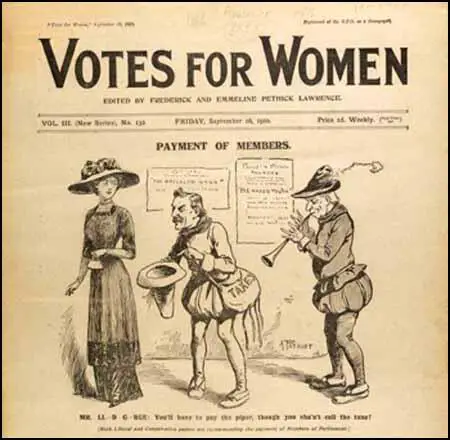

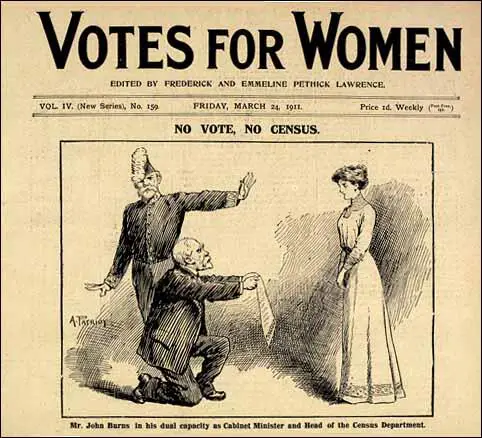

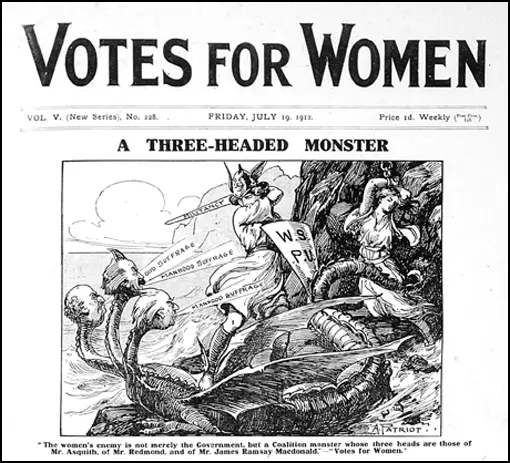

A strong supporter of women's suffrage, Pearse composed a weekly cartoon for the Women Social & Political Union newspaper, Votes for Women from 18th February 1909. (6) One of his most important cartoons depicts the force-feeding of an imprisoned suffragette on a hunger strike - "a practice that the government authorized in 1909". (7)

Alfred Pearse joined forces with Laurence Housman to form the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage) on 8th May 1909. (8) It claimed: "The object of the society is to encourage Artiststo forward the Women's movement, and particularly the Enfranchisement of Women, by means of pictorial publications. Each member of the Society shall undertake to give the Society first refusal of any pictorial work intended for publication, dealing with the women's movement. In return the artist will receive a certain percentage of the profits arising from the sale of her or his work." (9)

Muriel Matters of the Women's Freedom League was a strong supporter of this organisation. She argued that "she had found people who were impervious to argument and reason could be convinced by the postcard representing the lunatic and the lady, or an illustration of Mrs Poyser's classic remark on men and women." (10)

Alfred Pearse also provided drawings for The Vote, Votes for Women and The Suffragette using the name "A Patriot". He also produced several posters for the Women Social & Political Union. Some of his drawings were issued as postcards. Pearse also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (11)

During the First World War his "images of gallant deeds, war heroes, and war heroes, and war heroines were reproduced on postcards" and in the autumn of 1918, with the rank of captain, he accompanied the New Zealand Army to the Western Front as an official war artist. A friend described him as "a lovable character: generous and kind to all but his own interests." (12)

Alfred Pearse died in London 1933.

by the Women's Freedom League (February, 1911)

by the Women's Freedom League (February, 1911)

Primary Sources

(1) Philip V. Allingham, Alfred Pearse: Cartoonist, Illustrator and Advocate of Women's Rights (7th July, 2015)

English cartoonist, illustrator, and vigorous campaigner for women's equality, Alfred Pearse (1855–1933), who also signed himself as "A Patriot," was a fourth generation artist and son of celebrated decorative artist J. S. Pearse. Formally trained, he attended the West London School of Art, winning many prizes for his drawing. At the turn of the century, Alfred Pearse, now an established artist, was also regularly published in The Illustrated London News, the Boy's Own Paper, and the illustrated magazine of London humour Punch. Besides designing campaign posters advocating women's suffrage, Pearse composed a weekly cartoon for Votes for Women from 1909, and, with Laurence Housman, set up the Suffrage Atelier. In the next decade, Pearse produced various artworks, cartoons, and propaganda supporting British and her allies in World War One. He was not merely a competent wood engraver and solid book illustrator; he also acted as art critic for the Manchester Guardian.

(2) Claire Voon, British Suffrage Movement Posters Goes on Display (26th February, 2018)

The visual language, too, was diverse. Some posters were satirical, drawing from familiar 19th-century political caricatures, while others featured more evocative, emotional images. One poster by cartoonist Alfred Pearse (signed "A. Patriot") depicts the force-feeding of an imprisoned suffragette on a hunger strike - a practice that the government authorized in 1909.

The colorful pictures represented the voices of professional artists as well as everyday citizens - both women and men. Many of them are signed. The most famous among these creatives, arguably, is the painter Duncan Grant, who was a member of the modernist Bloomsbury Group. Others include Mary Sargant Florence, a mural painter, and Emily Jane Harding Andrews, a book illustrator. Harding Andrews created posters for the Artists' Suffrage League, one of two chief organizations in Britain that were responsible for producing poster and postcard designs. The League was established in 1907 by stained-glass artist Mary Lowndes, two years prior to the founding of the collective known as Suffrage Atelier. Formed specifically to gear up for a demonstration by the Women's Social and Political Union - the society set up by suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst - Suffrage Atelier favored using woodblocks to more quickly produce and distribute their posters.

For Britons, the century-old notices vividly capture the voices of overlooked individuals who fought for greater gender equality in their nation. For the rest of us, they're poignant reminders of the significant role grassroots movements play in enacting systemic change.

(3) Barbara Goff, A Three-Headed Monster (6th December, 2018)

The first edition of the Anti-Suffrage Review, in August 1910, contained a provocative article subtitled "If Sappho had never sung"; it concluded that although women are not intellectually inferior to men, "the sum total of human happiness, knowledge and achievement would have been almost unaffected if Sappho had never sung, if Joan of Arc had never fought, if Siddons had never played, and if George Eliot had never written". The author thus takes the women who are pointed out as representative by the suffragettes, and diminishes their impact; he goes on to say that the true functions of womanhood, which are not very clearly defined but which probably include the birth and rearing of children, are more important to society, and are threatened by any measure that gives women the vote. A number of suffrage supporters wrote replies to this kind of argument. Elizabeth Robins, writer, actor and suffragist, published Ancilla's Share in 1924, in which Sappho stands as the prime example of the way in which women can make outstanding cultural contributions, but have to pay the price of male antagonism. Typically for the time, Robins rejects the claims that Sappho was a woman who desired women, and suggests instead that her supreme poetic skill and talent incited the jealousy of men who then accused her of ‘the vice for which Lesbos sits through the centuries in the pillory of ill-repute'. Is there not a connection, she suggests, ‘between the fact that Lesbos was the nursing mother of intellectually free women, and man's uneasiness in face of the intellectually free woman unless she was socially ostracised?'

The Romans are perhaps slightly less useful to the suffragists than the Greeks, but the historian Tacitus is frequently cited for his praise of the warrior-like women of the ancient Germans, and the British leader Boudicca also features in several different contexts, as well as in the Pageant of Great Women. To construct a tradition of warlike women was important when suffragists were combating the argument that physical force, the ability to take up arms against the enemy, was a necessary qualification for the vote. One of the suffragists' own important arguments was that women should not remain unrepresented when they did have to pay taxes. A 1909 article on ‘Roman Suffragettes' helps out with this. It begins ‘The Suffragette studies history' and goes on to recount how Hortensia led the women of Rome in their refusal to contribute funds to the civil war. ‘It was Hortensia who enunciated on this occasion for the first time in history the principle of "no taxation without representation". "Why should we pay taxes," she cried, "when we have no part in the honours, the command, the statecraft, for which you contend against one another with such harmful results?"' The author of the article does not need to state the obvious conclusion.

Greek and Roman history and literature also contributed less serious material. Laurence Housman, brother of the poet A . E. Housman, translated Aristophanes' comic Lysistrata for performances by suffragists, who revelled in its portrayal of women ganging up on men to secure peace. Several writers in Votes for Women or Common Cause published parodies of Socratic dialogues, in which recalcitrant ‘antis' discovered, just like Socrates' interlocutors in Plato's originals, that they could not defend their unexamined prejudices...

This image, another example of the more humorous side of the suffrage struggle, draws on classical mythology, as well as British legends like St George and the dragon, to show the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) defending a bound woman against the three-headed monster of contemporary male political leadership. The battling militant wields the authority of the classical world, even while challenging other powerful narratives that would have consigned her to a very different version of history.