Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman was born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, on 18th July, 1865. His father, Edward Housman (1831–1894), was a solicitor who held very conservative views. His mother died when he was only five years old, leaving five sons (Laurence, Alfred Edward, Robert, Basil, and Herbert) and two daughters (Clemence and Kate) in their father's care. (1)

The children were educated by a governess, Miss Milward. After Edward's second marriage, to his cousin Lucy Housman, the family moved to nearby Fockbury House, Catshill. (2)

Laurence won a scholarship to be educated as a day boy at Bromsgrove School. According to one of his biographers, Katharine Cockin: Housman's schooldays made a lasting impression. He later compared the oppressive experiences of bullying and fagging with the subjugation of colonized countries under imperialism. The rigidly conservative political and religious influences of his childhood provoked a rebellious response and at eighteen years of age he broke away from his father's control." (3)

Assisted by a legacy of £500 each, Laurence and Clemence moved to London in November 1883. They found lodgings at 36 Camberwell New Road. (4) Laurence records in his autobiography, The Unexpected Years (1937), that it was only in order to look after him in London that Clemence was eventually "released from the Victorian bonds of home". (5)

Laurence Housman: Artist and Writer

Laurence Housman studied art at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A talented illustrator, his work was exhibited at the Baillie Gallery, the Fine Art Society, and the New English Art Club. His best known work includes Goblin Market (1893) and The Sensitive Plant (1898). He also published two volumes of poetry, Green Arras (1896) and Spikenard (1898). Laurence claimed that Clemence was his "literary mentor". (6)

Laurence also published two volumes of poetry, Green Arras (1896) and Spikenard (1898). He became a close friend of Oscar Wilde. In 1900 he created great controversy when he published anonymously, An Englishwoman's Love Letters. It was very successful and it is claimed he received over £2,000 in royalties. During this period he also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (7)

In 1906 Housman joined Harley Granville-Barker to produce a play, Prunella, or Death in a Dutch Garden. This was followed by a play, Pains and Penalties, about Queen Caroline, wife to George IV. It was refused a licence by the lord chamberlain. It was produced without licence by Edith Craig for a private performance for members of the Pioneer Players society, challenging the powers of the lord chamberlain. (8)

Women's Suffrage

Laurence Housman had been converted to the cause of women's suffrage by hearing a speech given by Emmeline Pankhurst. This resulted in him developing "that most uncomfortable thing a social conscience." He added "I was forced, against my inclination, into a higher standard of moral courage than I had ever practised before" and this began his involvement in the "political problems and controversies of the present day." (9)

In 1907, Laurence Housman joined with several other left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould and Charles Mansell-Moullin to formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." (10) In 1908 Housman gave his first donation to the WSPU. (11)

Clemence Housman joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). On 30th June, 1908, she took part in a meeting when it was announced that they intended to march to 10 Downing Street to meet H. H. Asquith. Housman was on the platform with Emmeline Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jessie Stephen, Mary Phillips, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Maud Joachim and Florence Haig. (12)

Suffrage Atelier

On 8th May 1909, Laurence and Clemence Housman joined Alfred Pearse to form the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage). (13) It claimed: "The object of the society is to encourage Artists to forward the Women's movement, and particularly the Enfranchisement of Women, by means of pictorial publications. Each member of the Society shall undertake to give the Society first refusal of any pictorial work intended for publication, dealing with the women's movement. In return the artist will receive a certain percentage of the profits arising from the sale of her or his work." (14)

As Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) has pointed out that along with the Artists' Suffrage League: "Women were able to organise collectively and contribute their professional skills to the suffrage campaign. They designed, printed and embroidered all manner of political material; they taught each other the requisite skills from hand-painting to needlework; they designed major demonstrations and took part in them in their own contingents; they lent their studios for meetings and contributed to exhibitions, bazaars and fund-raising activities." (15)

On 6th May 1911, Herbert Asquith, the prime minister of the Liberal Party government, announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. (16)

In an attempt to put pressure on the government, the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (17)

Other suffrage organisations including the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Women's Freedom League (WFL), Church League for Suffrage, Actresses' Franchise League, Artists' Suffrage League, Suffrage Atelier, Women's Tax Resistance League, Men's League For Women's Suffrage, Fabian Women's Group, Catholic Women's Suffrage Society and the Church Socialist League agreed to join the march. It was argued that "Everything depends on numbers, and if the deputation is sufficiently large, the authorities will be placed in an insurmountable difficulty." (18)

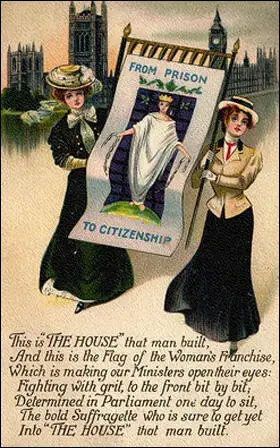

Laurence Housman was heavily involved in the making banners for the Coronation Procession. This included the banner "From Prison to Citizenship" under which "almost 1,000 ex-prisoners marched". The banner was made by Clemence from a design by Laurence. Soon afterwards it was featured on a postcard that was published in a series of twelve entitled, "The House that Man Built." (19)

by Clemence Housman from a design by Laurence Housman (1911)

The Suffrage Atelier was based at 1, Pembroke Cottages, Edwardes Square, the home of Laurence and Clemence Housman. Laurence described his sister as the organistion's "chief worker" and the main "banner-maker" of the women's suffrage campaign. (20) In 1911 she made a new banner for the Actresses' Franchise League. "Stencilled in the AFL colours of pink, white, and green, it shows the twin masks of tragedy and comedy framed with wreaths and ribbons." (21)

Tax Resistance League

Clemence Housman was on the committee of the Women's Tax Resistance League. She stated that she refused "to pay her taxes until such time as women are enfranchised". In 1909 Clemence Housman took a house, for which she was taxed inhabited house duty to the amount of 4s. 6d. "This, since she was denied all Parliamentary representation, she refused to pay." It was not until July, 1911, that she received a letter from the Board of Inland Revenue, "stating that legal proceedings had been taken for the recovery of the inhabited house duty, amounted to 4s. 6d. and that unless the tax, plus the costs and out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to £4 18s. 6d., were paid steps would be taken for her arrest and imprisonment." (22)

Clemence refused to pay the fine and on Friday 30th September, she was arrested and conveyed to Holloway Prison. On 7th October a meeting was held to protest about her imprisonment. Laurence Housman, Christabel Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard all made speeches. Pankhurst quoted Clemence as saying. "Holloway is women's polling booth; it is there that I have been able to register my vote against a Government that taxes me without representation." Despard talked about her "courageous act of self-sacrifice, and said that tax resistance was drawing women together in a bond as strong as death." (23)

At the end of the meeting the Women's Tax Resistance League issued a statement. "That this meeting, held at the gates of Holloway Gaol, congratulates Miss Clemence Housman on her refusal to pay Crown taxes without representation, a reassertion of that principle upon which Englishman now enjoy, and also upon the successful outcome of her protest. It condemns the Government's actions in ordering her arrest and imprisonment as a violation of the spirit of the Constitution and of representative government; and it calls upon the Government to give votes to women before again demanding from Miss Housman or any other woman taxpayer the payments of taxes." (24) As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "She (Housman) was released after a week, no reason being given, and did not pay her debt until she received the right to vote." (25)

His biographer, Katharine Cockin has pointed out: "Housman was disgusted by the sexual discrimination in favour of male supporters of women's suffrage, as his arrest for protesting against the forcible feeding of hunger-striking suffragists, unlike that of the female protesters, did not result in imprisonment." (26)

Women's Freedom League

Initially most members of the Suffrage Atelier were members of the Women Social & Political Union. However, several members became critical of its arson campaign and left the organisation. Laurence Housman, one of the co-founders of the Suffrage Atelier was especially critical of the WSPU. He was especially upset when Mary Richardson attacked the painting, Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. Housman described the "stab in the back given to the Rokeby Venus" as hurting his artistic feelings. "After that came the burning of churches, and I felt myself obliged to cease subscribing to WSPU funds." (27)

The Suffrage Atelier now became closely associated with the militant but non-violent, Women's Freedom League (WFL) with which it embarked on the joint venture of a "pictorial supplement" with its newspaper, The Vote. (28) In 1912 the WFL worked with the Atelier on a new poster campaign. Charlotte Despard, the leader of the WFL, wrote that their joint campaign would bring the Atelier's work "into more intimate relation" with the movement and the public as a whole, while at the same time illustrating "the advance of the Cause and the fluctuations of the political barometer". (29)

On 6th February 1914 a group of supporters of women's suffrage, including Laurence Housman, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement. Other members included Henry Harben, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Neal, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Barbara Ayrton Gould, Gerald Gould, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr and Julia Scurr. (30)

First World War

Most members of the Women's Freedom League and the United Suffragists, were pacifists, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 they refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Crusade for a negotiated peace. The Vote attacked Christabel Pankhurst and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, for condemning the women's peace conference. (31) (6)

During the First World War he worked closely with Sylvia Pankhurst and wrote for her newspaper, The Workers' Dreadnought. In 1916 he visited the United States on a lecture tour in support of the League of Nations. He was also a member of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology and the Independent Labour Party. (32)

Victoria Regina

After his eyesight began to fail he turned to writing books and plays, including Angels and Ministers (1921), and Little Plays of St. Francis (1922). Housman wrote a series of short plays dealing with episodes in the life of Queen Victoria, which he later incorporated in one under the title of Victoria Regina. However, at the time, the censor's ruling was that no British monarch could be portrayed on the stage in Britain during his or her lifetime or the lifetime of any children. Through the intervention of Edward VIII, just before his abdication in December, 1936, the ban was lifted. "The play was an immediate success, and during its long run the weekly takings never dropped before £2,000, the average being about £2,300." (33)

Laurence Housman's autobiography, The Unexpected Years, appeared in 1937. Katharine Cockin argues that the book "is of interest in its representations of his upbringing, and the cultural and political milieu of his times in London, but reticent on his homosexuality". (34)

Pacifism

Houseman was a strong supporter of the Peace Pledge Union. In 1945 the organization opened Housmans Bookshop in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, and it became a major source of literature on pacifism. In the 1950s Housman was a supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In 1952 Housman joined the Society of Friends. (35)

Clemence suffered a severe stroke in 1953, and was cared for assiduously by Laurence. (36) Clemence Housman died on 6th December 1955 at Mount Avalon, Glastonbury, having suffered a further stroke, and was buried at Smallcombe cemetery outside Bath. It was reported that Clemence and Laurence had "been inseparable for seventy years." (37)

Laurence Housman died on 20th February 1959 in Butleigh Hospital in Glastonbury, Somerset.

Primary Sources

(1) The Vote (14th October 1911)

Miss Christabel Pankhurst was in her place on the cart, surrounded by the speakers. One's eyes were rivetted by the sight of the tall, self-possessed lady, quiet and undemonstrative, who scarcely twenty-four hours before had been inside those prison walls. The singing and the enthusiasm were to reach her in her cell, but the action of the authorities in releasing Miss Housman enabled her to be seen instead of the unseen centre of the demonstration. Her words, too, carried great weight. Humorously she contrasted the treatment of men voters and voteless women: agents to do everything for the men, motors to take them to the polling booth….

Turning to the prison, Miss Housman exclaiming dramatically. "Holloway is women's polling booth; it is there that I have been able to register my vote against a Government that taxes me without representation." Only words of courtesy were heard concerning all the officials with whom Miss Housman had come into contact, and she was cheered to the echo when she declared that, glad as she was to be outside Holloway, she was ready to go back again to win the fight for the recognition of women's citizenship.

"If that great act of justice, the Conciliation Bill, fails to carry next year, there will be not merely one but hundreds of women in prison to make the nation realise that justice is not being done." Thus spoke Mr. Laurence Housman, whose pride in his sister's devotion to the woman's cause was shared by those who listened. Women were only doing what men had gloried in doing in times past, he added, they were struggling for constitutional liberties; women, too, had caught the spirit of democracy. Mrs. Despard, heedless of the drenching rain, made an appeal which touched the hearts of all who heard it; she rejoiced to the victory won by Miss Housman's courageous act of self-sacrifice, and said that tax resistance was drawing women together in a bond as strong as death.

(2) Aberdeen Evening Express (20th February 1959)

Laurence Housman, the author and playwright, died today in Burleigh Hospital, Somerset, aged ninety-three.

Mr. Housman used to refer to himself as "the most censored playwright in England, but the most respectable."

For more than thirty-five years he was in conflict with the Lord Chamberlain office over the censorship of various of his plays. Altogether he had over thirty plays banned at one time or another.

His most famous struggle, however, was over his series of short plays dealing with episodes in the life of Queen Victoria, which he later incorporated in one under the title of "Victoria Regina".

The censor's ruling was that no British monarch could be portrayed on the stage in Britain during his or her lifetime or the lifetime of any children.

Through the intervention of King Edward VIII, just before his abdication in December, 1936, the ban was lifted.

The play was an immediate success, and during its long run the weekly takings never dropped before £2,000, the average being about £2,300.

Mr. Housman was a bachelor. He gave as a reason for not marrying that in his earlier years his small income made it impossible for him to marry a woman of "the class to which I was supposed to belong."

He and his sister, Clemence Housman four years his senior had lived in an old-world cottage at Street. She was for long his literary mentor. They had been inseparable for seventy years until her death in December, 1955.

In a BBC interview on "the experience of age" in June, 1953, Mr Housman gave himself two more years to live.

He said: "I would be as fully ripe by ninety as I would hope to be. The thing that follows after ripeness is rot."

Mr. Housman was a Quaker, a pacifist, and a vegetarian.