Coronation Procession (17th June 1911)

On 6th May 1911, Herbert Asquith, the prime minister, announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. (1)

In an attempt to put pressure on the government, the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (2)

Other suffrage organisations including the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Women's Freedom League (WFL), Church League for Suffrage, Actresses' Franchise League, Artists' Suffrage League, Suffrage Atelier, Women's Tax Resistance League, Men's League For Women's Suffrage, Fabian Women's Group, Catholic Women's Suffrage Society and the Church Socialist League agreed to join the march. It was argued that "Everything depends on numbers, and if the deputation is sufficiently large, the authorities will be placed in an insurmountable difficulty." (3)

In an attempt to get a large turnout women canvassed door to door, distributed handbills, fly-posted, carried flags in the streets and chalked announcements on pavements. WSPU opened pop-up shops all over London that sold mass-produced, branded suffragette merchandise. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence came up with the idea of publicizing the march by the distribution of a quarter of a million purple, white and green mock railway tickets. (4)

Initially the plan was for the women to march seven abreast but the police insisted it should be no more than five abreast. (5) Kate Harvey organized the procession for the WFL and Edith Downing and Marion Wallace-Dunlop played this role for the WSPU: As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "This represented an immense amount of work. The creation of a wide range of costumes to dress those taking part in the Historical Pageant was particularly taxing. Groups, suitably attired, representing women of renown from the 'early Middle Ages, the Reformation period and in recent history', each carrying an appropriate banner, were designed to impress onlookers with the scope of women's public work through the centuries." (6)

The day before the march took place Prime Minister Herbert Asquith sent a message that convinced the WSPU leadership that votes for women were about to be granted. Christabel Pankhurst wrote: "how much relieved we are by the Prime Minister's message which does really seemed to give us an assurance on which we can depend and can make the basis of our work for the coming months." (7)

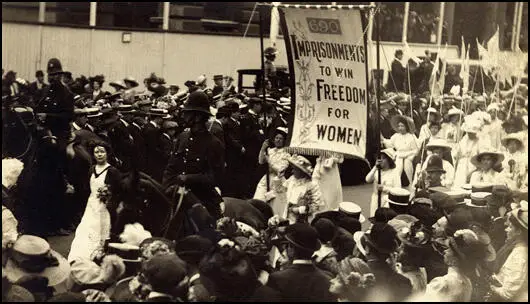

Charlotte Despard led the procession on behalf of the Women's Freedom League. It's newspaper, The Vote, reported: "At half-past five the procession started from the Embankment and came swinging along at a good pace up Northumberland Avenue. The roads were packed with such dense crowds that in some parts the police had considerable difficulty in clearing a way for it… Forty thousand women's marching through London forty thousand women walking five abreast, with pennants flying abreast, with pennants flying, banners held aloft, colours of every hue and shade and gradation blazing in the sun; forty thousand women with faces to the dawn, women of every rank and party and creed and race and colour, women old and young, rich and poor; comrades all in the cause of freedoom." (8)

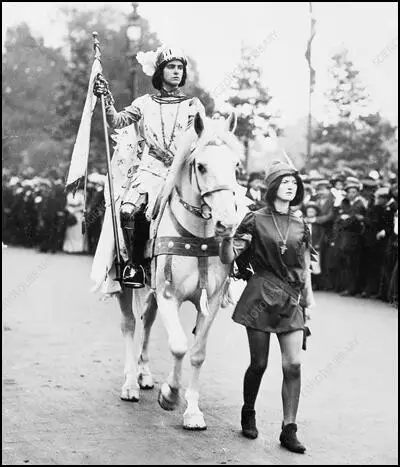

The march was led by General Flora Drummond on a horse. Then came Charlotte Marsh carrying a Women Social & Political Union flag. She was followed by 19-year-old Margery Bryce, dressed as the Women Social & Political Union's patron saint, Joan of Arc, led the procession on a white horse and in full armour. (9) Her sister, Rosalind Bryce, aged 16, dressed as a medieval page, led the horse by the bridle. (Their father, Annan Bryce, MP for the Inverness Burghs, was completely opposed to votes for women. They were followed by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Mabel Tuke. (10)

Literature was represented in the procession by writers, actresses, composers, singers and musicians. This included Elizabeth Robins, Beatrice Harraden, Cicely Hamilton, Alice Meynell, Evelyn Sharp, Lena Ashwell, Ethel Smyth, Lillah McCarthy, Flora Annie Steel, Sarah Grand, Eva Moore, Decima Moore and Yvette Guilbert. (11)

It was pointed out: "Every profession and trade that women have forced themselves into set its contingent to swell the ranks. Actresses, artists, gardeners, gymnastic teachers, writers, clerks, business women and doctors in their hundreds came quickly after the beautiful symbolic Empire Car, which was a mass of roses." (12)

The Colonial Section was led by New Zealand, the first country to give women full political rights. Vida Goldstein led the procession on behalf of Australia, who had granted women full and equal franchise was extended in 1902. Also there was Margaret Fisher, the wife of Andrew Fisher, the Prime Minister of Australia. There were also a group of Indian suffragettes in the procession. (13)

Henry Nevinson pointed out that Charlotte Despard was well-received by the people watching the march: "Mrs Despard at its head (of the Women's Freedom League delegation), certainly one of the most conspicuous personalities in the demonstration, was recognised and acclaimed by all classes, but especially by the poor, and no man in the Procession seemed so widely known as Mr. Lansbury." (14)

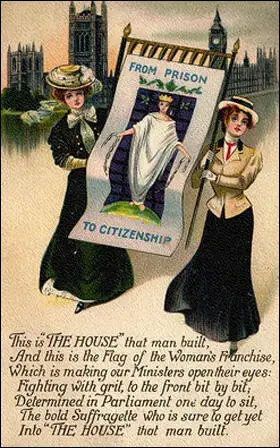

Clemence Housman and her brother, Laurence Housman, were heavily involved in the making banners for the Coronation Procession. This included the banner "From Prison to Citizenship" under which "almost 1,000 ex-prisoners marched". The banner was made by Clemence from a design by Laurence. Soon afterwards it was featured on a postcard that was published in a series of twelve entitled, "The House that Man Built." (15)

by Clemence Housman from a design by Laurence Housman (1911)

It was pointed out that the march was well-received by the people who lined the streets: "The reception according to the army of women joyously confident in the righteousness of their cause, proud of the glorious opportunity of demonstrating their firm-fixed resolve to gain the rights of citizenship and sure of victory in the very near future, was undoubtedly sympathetic. By comparisons with previous processions the absence of any expression of hostility on the part of any considerable section of the public was most marked. Instead, there was unmistakable evidence all along the route that the movement had won the respect and, to a degree never before evinced, the approvable of the people." (16)

The Women's Freedom League used banners that celebrated some of their successful activities such as the Women's Tax Resistance League campaign. They had a banner that explained how Helen Fox and Muriel Matters managed to chain themselves to the Ladies' Gallery Grille of the House of Commons in October 1908. They also had a banner Bermondsey By-Election protest by Alison Neilans and Alice Chapin in October 1909. (17)

It is estimated that over 40,000 women marched to seventy-five bands and held over a thousand embroidered and painted banners. 700 women were clothed in white to represent suffragette prisoners. The "Famous Women's Pageant" had twenty suffragettes dressed up as notable women from the past, including, Josephine Butler, Florence Nightingale, Lydia Becker, Elizabeth Fry, Harriet Martineau, Charlotte Bronte, Mary Somerville and Grace Darling. (18)

The Men's League For Women's Suffrage delegation was at the rear of the march. It was led by George Lansbury, Israel Zangwill and Alexander Webbe. The journalist, Henry Nevinson, joined the other men on the march as it reached Green Park. "The Men's League was remarkably strong, numbering some hundreds, and including Mr Zangwill and Mr. A. J. Webbe as first-rate representatives of literature and sport. As I had been instructed I fell in at the head of the Men's Political Union to carry their colours for the rest of the march. Five years ago I had never supposed that I should one day advance down Piccadilly on horseback carrying a huge flag of purple, white and green resting on one shoulder or raised high above my head." (19)

The 78-year-old, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, was the guest of honour. It was claimed that as the oldest militant suffragist still alive she had "spent 46 years of her life in fighting for the vote." (20) Emmeline Pankhurst made the main speech at the end of the march. She said that "the keynote of their movement was co-operation with men with the object of building up a better and brighter type of humanity." (21)

Christabel Pankhurst moved the resolution: "That this meeting rejoices in the coming triumph of the votes for women cause, and pledges itself to use any and every means necessary to turn to account the Prime Minister's pledge of full and effective facilities for the Women's Enfranchise Bill." The resolution, which was seconded by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and supported by Annie Besant, was carried amid much fervour and enthusiasm". (22)

The Women's Coronation March impressed the national newspapers. The Daily Chronicle remarked: "Saturday's remarkable procession in London served as a prelude to the inevitable triumph." (23) The Daily Mirror praised the large number of working-class women who were dressed as mill workers and weavers. "These brave tired women, who had left their homes to demonstrate for their fellow-toilers, were loudly cheered by the crowd." (24)

Another newspaper reported: "Even the most unimaginative person who witnessed the moving panorama which was unfolded to the delight and wonderment of the myriads of spectators who came out to see it must, we should suppose, have been impressed with the meaning of it... All sections of the Suffragist movement eagerly and cheerfully co-operated and it is claimed that no section of womanhood in the United Kingdom was unrepresented in its ranks… The streets through which it passed were thronged with onlookers to an extent which has rarely been surpassed, except on the occasion of some great national or royal ceremonial of the first importance… Altogether it was a remarkable picture of colour and of movement, and one the like of which has probably never before been seen in any city in the world." (25)

It is claimed that more than £100,000 was raised as a result of the march. (26) In addition women removed their jewellery and placed it on collection plates. According to The Times "women moved quietly towards the platform from all parts of the building carrying promissory cards, and the treasurer, speaking at the rate of several hundred pounds a minute, read their contents aloud... there was not time to finish the counting of the promised subscriptions before the end of the meeting." (27)

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (16th June 1911)

Owing to the representations made to us by the Police at the last moment, and at their express wish, the Procession will march five abreast instead of the seven, as was originally announced.

The greatest procession of women ever seen since the world began marches on Saturday through the streets of the world's greatest city, and the large majority of those in its ranks are not even "persons" in the eyes of the law! Does the average looker-on at this great spectacle realise the public rights and duties to which women from all over the world lay claim today were exercised by women of the Mother Country, they have already been accorded to the women of some of the Daughter Colonies.

Something of this will be shown in the Pageant of Empire. The Colonial Section is led by New Zealand, the first country under the Crown to give women full political rights. This is headed by Lady Stout, a wife of the Chief Justice of the Colony, accompanied by Mrs. Macmillan, chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and Governor of St. John's College Dr Burn carries the standard.

Australia, to whose women full and equal franchise was extended in 1902, the Coronation year of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, follows, led by Mrs Fisher, wife of the Prime Minister of Australia. In the ranks will be Lady Cockburn, wife of Sir John Cockburn, Agent-General for South Australia; Mrs Bowman, wife of the Leader of the Opposition, Queensland Parliament: Miss Vida Goldstein, Leader of the Women's Party in Victoria…

No section of womanhood in the United Kingdom is unrepresented in the great procession. Women engaged in organised industries and trades, women whose sphere of labour is the home, women who hold an honoured place in professions, women who lives have been spent in the service of humanity – all will be in the ranks. All the learned profession, science, literature, the drama, music, art, and the skilled handicrafts are accorded a place of honour.

Literature will be represented in the procession by such writers as Elizabeth Robins, Beatrice Harraden, Flora Annie Steel, Sarah Grand, Cicely Hamilton, Alice Meynell, Evelyn Sharp and Israel Zangwill: the drama by Lena Ashwell, Lillah McCarthy, Eva Moore, Decima Moore, Yvette Guilbert…

Amongst the musicians Dr. Ethel Smyth will be walking in her robes… One of the most notable figures will be that of Mrs Annie Besant, who will be one of the speakers at the mass meeting at the Albert Hall at 8.30 in the evening. Muriel Countess de la Warr and the Ladies Idina and Alice Sackville will be among the marchers…

The entire Procession will be reviewed by Mrs Wolstenholme Elmy, the oldest militant suffragist who has spent 46 years of her life in fighting for the vote.

(2) The Lincolnshire Echo (19th June 1911)

Apart from the Coronation itself nothing of greater historical significance has taken place in 1911 then the Women's Pageant and Procession on Saturday last. Women of every rank, every calling, of every shade of political and religious opinion, from England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and India united to form a procession five miles in length, walking five miles in length, walking five abreast to the music of 100 bands. Starting at 5.30 with a colour bearer heralding Joan of Arc, the pageant passed through the tens of thousands of people grouped to watch the passing.

Every profession and trade that women have forced themselves into set its contingent to swell the ranks. Actresses, artists, gardeners, gymnastic teachers, writers, clerks, business women and doctors in their hundreds came quickly after the beautiful symbolic Empire Car, which was a mass of roses.

(3) Hants and Sussex News (21st June, 1911)

Even the most unimaginative person who witnessed the moving panorama which was unfolded to the delight and wonderment of the myriads of spectators who came out to see it must, we should suppose, have been impressed with the meaning of it…

All sections of the Suffragist movement eagerly and cheerfully co-operated and it is claimed that no section of womanhood in the United Kingdom was unrepresented in its ranks…. The Men's Societies for Women's Enfranchisement being stationed in the rear…

The streets through which it passed were thronged with onlookers to an extent which has rarely been surpassed, except on the occasion of some great national or royal ceremonial of the first importance… Altogether it was a remarkable picture of colour and of movement, and one the like of which has probably never before been seen in any city in the world.

The reception according to the army of women joyously confident in the righteousness of their cause, proud of the glorious opportunity of demonstrating their firm-fixed resolve to gain the rights of citizenship and sure of victory in the very near future, was undoubtedly sympathetic. By comparisons with previous processions the absence of any expression of hostility on the part of any considerable section of the public was most marked. Instead, there was unmistakable evidence all along the route that the movement had won the respect and, to a degree never before evinced, the approvable of the people.

Mrs Pankhurst in opening said the keynote of their movement was co-operation with men with the object of building up a better and brighter type of humanity.

(4) Henry Nevinson, Votes for Women (23rd June 1911)

General Drummond rode first – composed, smiling, universally welcomed as she always is. And then came Miss Charlotte Marsh with the colours, holding her place by the right of martyrdom; and then Miss Annan Bryce, a beautiful, militant Joan of Arc; and then the splendid little group of New Crusaders. They all formed a glorious heraldry…

Mrs Despard at its head (of the Women's Freedom League delegation), certainly one of the most conspicuous personalities in the demonstration, was recognised and acclaimed by all classes, but especially by the poor, and no man in the Procession seemed so widely known as Mr. Lansbury…

One episode stands out conspicuous in everyone's memory during the long hours of that march. It was when, in passing the Green Park, when at last I saw the banners of the Men's Political Union bringing up the rear. The Men's League was remarkably strong, numbering some hundreds, and including Mr Zangwill and Mr. A. J. Webbe as first-rate representatives of literature and sport. As I had been instructed I fell in at the head of the Men's Political Union to carry their colours for the rest of the march. Five years ago I had never supposed that I should one day advance down Piccadilly on horseback carrying a huge flag of purple, white and green resting on one shoulder or raised high above my head.

(5) The Vote (24th June, 1911)

Forty thousand women's marching through London forty thousand women walking five abreast, with pennants flying abreast, with pennants flying, banners held aloft, colours of every hue and shade and gradation blazing in the sun; forty thousand women with faces to the dawn, women of every rank and party and creed and race and colour, women old and young, rich and poor; comrades all in the cause of freedom…

At half-past five the procession started from the Embankment and came swinging along at a good pace up Northumberland Avenue. The roads were packed with such dense crowds that in some parts the police had considerable difficulty in clearing a way for it…

The Police Court Protests banner, Marshalled by Miss Turner, and followed by fourteen members of the League, bore the words; "Legislation Without Representation is Slavery." Next to this was carried the Tax Resistance banner, showing that the Women's Freedom League initiated tax resistance in 1907.

The Grille Protest banner, depicting the grille and the chains, come next, followed by a large number of representatives of the famous protests marshalled by Mrs. De Vismes. The Picketers' banner bore the words: "729 hours were spent in Picketing the House of Commons to Exercise the Subjects Right of Petitioning the King's Ministers." The picketers made a brave show with their flying pennants of green, of gold, and of white. The Bermondsey Ballot-Box banner, which celebrated the ballot-box protest made by Mrs Chapin and Miss Alison Neilans, chronicled the fact that the protest was initiated in 1909 by the League.

In November 1910, in protest at the failure of the first Conciliation Bill, Emmeline Pankhurst convened a huge meeting and enjoined the audience to "come with me to the House of Commons". Hundreds of women followed her. It looked as though the truce was at an end, but the brutality of the police that evening was disgusting enough to swing the pendulum of public opinion towards the protesters. Brailsford himself took charge of the collection of evidence from the demonstrators. His report contained enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely. Its impact went way beyond the bounds of the Woman's Press, which had commissioned it. The report, and the new Liberal Government that took office after the election of December 1910, also bought more time for the WSPU truce on militancy. The truce held while a new Conciliation Bill was published without the £10 property qualification for voting that had been in the first Bill, and without an express ban on husbands and wives voting together. In a sudden surge of public and parliamentary enthusiasm, the second reading of this Bill passed the Commons on 5 May 1911 with a majority of 167, and for a brief moment it seemed to Brailsford, Nevinson and company that their prodigious negotiations had been worthwhile:

They were reckoning without top Liberal politicians, in particular the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George. Lloyd George loved high office. He was not remotely interested in votes for women, and he regarded the campaigners, especially the militant ones, as an infernal nuisance. On the other hand, he understood that the Conciliation Committee posed a problem for the Government. A Commons majority of 167 could hardly be ignored, especially when the Bill had been passed two years running. But Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Tory Party. The problem called for what Lloyd George would have described as diplomacy, but quickly turned out to be duplicity. After stalling the WSPU all through the summer, Lloyd George started secret discussions with Brailsford and the Conciliation Committee. On 7 November 1911, he told the Committee he would support the Conciliation Bill if another Bill to introduce manhood suffrage failed. No such Bill had even been suggested, but, as if by magic, the following day Prime Minister Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise most men - a Bill that, he promised, could be amended to include women.

(6) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018)

For the 17 June 1911 Coronation Procession, Edith Downing and Marion Wallace-Dunlop again worked together, creating the Prisoner' Pageant, the Historical Pageant and the Pageant of Empire. This represented an immense amount of work. The creation of a wide range of costumes to dress those taking part in the Historical Pageant was particularly taxing. Groups, suitably attired, representing women of renown from the 'early Middle Ages, the Reformation period and in recent history', each carrying an appropriate banner, were designed to impress onlookers with the scope of women's public work through the centuries.