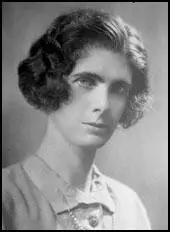

Margery Bryce

Margaret Vincentia Bryce, the daughter of John Annan Bryce and mother Violet L'Estrange Bryce was born on 18th June 1891. Her father was a partner of Wallace Brothers, East India merchants, and the family lived in Rangoon and on the legislative council of Burma. (1)

In 1906 John Annan Bryce was elected as Liberal MP for the Inverness Burghs. The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. (2)

However, Bryce voted against the measure as he was opposed to the measure. He also had letters published in The Times where he opposed the idea of women having the vote. (3) Bryce's wife disagreed strongly with him on this issue. She was related to two suffragists, Constance Markievicz and Eva Gore-Booth. (4) Votes for Women reported that Violet Bryce was unwilling to help her husband in the 1910 General Election "owing to his anti-Suffragist views, she is not prepared to help him in the contest." (5)

Margery Bryce and WSPU

Violet and Margery began going to Women Social & Political Union meetings. It was reported that along with Constance Lytton, Ethel Smyth, Idina Sackville and Vita Sackville West, she heard a speech by Emmeline Pankhurst at a meeting held at the home of Muriel de la Warr. Pankhurst said she regretted that there was so much misunderstanding and misinterpretation in regard to the movement and explained that the aim was to remove the sex disability. "The present position of affairs was not only injurious to women themselves, but to the State, and her remark that if women had the vote they would be able to influence legislation affecting their sex and children with which men were not competent to deal roused the cheers of the audiences." (6)

The Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith agreed with Bryce and made it clear that he intended to shelve the bill. Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (7) Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (8)

Violet and Margaret Bryce joined the WSPU and began to hold meetings at their house in Bryanston Square. Eugenie Bouvier gave two lectures on the subject of women's suffrage. "Speaking of the position of women throughout Europe, M. Bouvier said that it was a barbaric survival of the time when women was the property of men. All had changed except the attitude of men towards women, which was still primeval. Take for instance the question of morality. Men had instituted two standards - not merely one for men and the other for women, but, one might also say, one for men and the other against women." (9)

On 6th May 1911, Herbert Asquith, the prime minister, announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. (10)

Women's Coronation Procession

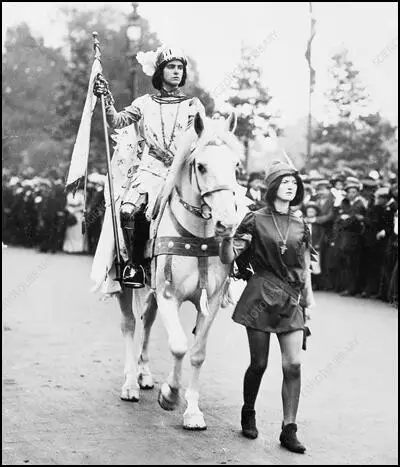

In an attempt to put pressure on the government, the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Margery Bryce agreed to play an important role in the march. (11) Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (12)

In an attempt to get a large turnout women canvassed door to door, distributed handbills, fly-posted, carried flags in the streets and chalked announcements on pavements. WSPU opened pop-up shops all over London that sold mass-produced, branded suffragette merchandise. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence came up with the idea of publicizing the march by the distribution of a quarter of a million purple, white and green mock railway tickets. (13)

Initially the plan was for the women to march seven abreast but the police insisted it should be no more than five abreast. (14) Kate Harvey organized the procession for the WFL and Edith Downing and Marion Wallace-Dunlop played this role for the WSPU: As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "This represented an immense amount of work. The creation of a wide range of costumes to dress those taking part in the Historical Pageant was particularly taxing. Groups, suitably attired, representing women of renown from the 'early Middle Ages, the Reformation period and in recent history', each carrying an appropriate banner, were designed to impress onlookers with the scope of women's public work through the centuries." (15)

The day before the march took place Prime Minister Herbert Asquith sent a message that convinced the WSPU leadership that votes for women were about to be granted. Christabel Pankhurst wrote: "how much relieved we are by the Prime Minister's message which does really seemed to give us an assurance on which we can depend and can make the basis of our work for the coming months." (16)

The march was led by General Flora Drummond on a horse. Then came Charlotte Marsh carrying a Women Social & Political Union flag. She was followed by 19-year-old Margery Bryce, dressed as the Women Social & Political Union's patron saint, Joan of Arc, led the procession on a white horse and in full armour. (17) Her sister, Rosalind Bryce, aged 16, dressed as a medieval page, led the horse by the bridle. (Their father, Annan Bryce, MP for the Inverness Burghs, was completely opposed to votes for women. They were followed by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Mabel Tuke. (18)

It was pointed out that the march was well-received by the people who lined the streets: "The reception according to the army of women joyously confident in the righteousness of their cause, proud of the glorious opportunity of demonstrating their firm-fixed resolve to gain the rights of citizenship and sure of victory in the very near future, was undoubtedly sympathetic. By comparisons with previous processions the absence of any expression of hostility on the part of any considerable section of the public was most marked. Instead, there was unmistakable evidence all along the route that the movement had won the respect and, to a degree never before evinced, the approvable of the people." (19)

The 78-year-old, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, was the guest of honour. It was claimed that as the oldest militant suffragist still alive she had "spent 46 years of her life in fighting for the vote." (20) Emmeline Pankhurst made the main speech at the end of the march. She said that "the keynote of their movement was co-operation with men with the object of building up a better and brighter type of humanity." (21)

Christabel Pankhurst moved the resolution: "That this meeting rejoices in the coming triumph of the votes for women cause, and pledges itself to use any and every means necessary to turn to account the Prime Minister's pledge of full and effective facilities for the Women's Enfranchise Bill." The resolution, which was seconded by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and supported by Annie Besant, was carried amid much fervour and enthusiasm". (22)

The Women's Coronation March impressed the national newspapers. The Daily Chronicle remarked: "Saturday's remarkable procession in London served as a prelude to the inevitable triumph." (23) The Daily Mirror praised the large number of working-class women who were dressed as mill workers and weavers. "These brave tired women, who had left their homes to demonstrate for their fellow-toilers, were loudly cheered by the crowd." (24)

Another newspaper reported: "Even the most unimaginative person who witnessed the moving panorama which was unfolded to the delight and wonderment of the myriads of spectators who came out to see it must, we should suppose, have been impressed with the meaning of it... All sections of the Suffragist movement eagerly and cheerfully co-operated and it is claimed that no section of womanhood in the United Kingdom was unrepresented in its ranks… The streets through which it passed were thronged with onlookers to an extent which has rarely been surpassed, except on the occasion of some great national or royal ceremonial of the first importance… Altogether it was a remarkable picture of colour and of movement, and one the like of which has probably never before been seen in any city in the world." (25)

It is claimed that more than £100,000 was raised as a result of the march. (26) In addition women removed their jewellery and placed it on collection plates. According to The Times "women moved quietly towards the platform from all parts of the building carrying promissory cards, and the treasurer, speaking at the rate of several hundred pounds a minute, read their contents aloud... there was not time to finish the counting of the promised subscriptions before the end of the meeting." (27)

Acting Career

After the First World War Margery Bryce became an actress. She appeared in the play The Sneezing Charm by Clifford Bax at the Court Theatre, London (1917-18). Bryce followed this with Husbands for All (1920) by the feminist writer, Gertrude E. Jennings. Although the play was not liked her performance was described as "excellent". (28) Later that year she played along side Ethel Irving and Edith Evans in the Arts Theatre production of the Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekov. (29)

In September 1920 she appeared in The Prude's Fall, a play by Rudolf Besier and May Edginton. Bryce was praised for her performance as a parlourmaid. "A more alarming domestic than Miss Margery Bryce can hardly be imagined. Her beetle-browed elegance and icy propriety must be more alarming to visitors and owner alike than an enraged bulldog." (30)

Bryce also acted in Henry V (1921), The Taming of the Shrew (1928), Runaways (1928), Back to Methuselah (1928), Six Characters in Search of an Author (1928), Harold (1928), The Taming of the Shrew (1928) and Mayor (1929). Bryce also appeared as Tatiana in The Cloud that Lifted by Maurice Maeterlinck at the Faculty Theatre, Piccadilly. The Stage reported: In the dialogue Tatiana is spoken of as a child, of innocent simplicity, living in a fairy world. But at the Faculty the part was sustained with emotional force, rather on tragedy-queen lines by Miss Margery Bryce, an elegant and graceful woman, but by no means a child." (31)

Margery Bryce appeared as Aunt Augusta in the highly successful Whiteoaks (1936-1938) at the Little Theatre, John Street. The play is based on the Jalna novels of Mazo De La Roche. Bryce reprised the role in 1951 at the Connaught Theatre. The Worthing Herald praised her acting as "all whalebone and indignation as Aunt Augusta." (32)

Margery Bryce died in Fulham on 8th June 1973.

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (7th January 1910)

Mrs Bryce, wife of J. Annan Bryce, the Liberal candidate for the Inverness Burghs, has declared her intention of remaining in the USA over the General Election, because, owing to his anti-Suffragist views, she is not prepared to help him in the contest.

(2) Votes for Women (11th November 1910)

Through the kindness of Lady Brassey, Mrs. Pankhurst addressed a large and influential audience at 24, Park Lane, on November 1, Lord Brassey was the chair, and among those who accepted invitations were: - The Duchess of Marlborough, Countess Torby… Mrs. Sackville West…. Lady Constance Lytton, Miss Ethel Smythe… Mrs Earl, Mrs. Annan Bryce and Miss Bryce… Mrs. Bernard Shaw.

Mrs. Pankhurst regretted that there was so much misunderstanding and misinterpretation in regard to the movement and explained that the aim was to remove the sex disability. The present position of affairs was not only injurious to women themselves, but to the State, and her remark that if women had the vote they would be able to influence legislation affecting their sex and children with which men were not competent to deal roused the cheers of the audiences.

(3) Votes for Women (14th April 1911)

The most interesting lectures were given on March 31 and April 4 by M. Eugenie Bouvier, Officer de l'Academie Francaise, at 35, Bryanston Square (by permission of Mrs. Annan Bryce), when Prince V. Bariatinsky was in the chair. Speaking of the position of women throughout Europe, M. Bouvier said that it was a barbaric survival of the time when women was the property of men. All had changed except the attitude of men towards women, which was still primeval. Take for instance the question of morality. Men had instituted two standards – not merely one for men and the other for women, but, one might also say, one for men and the other against women.

(4) Henry Nevinson, Votes for Women (23rd June 1911)

General Drummond rode first – composed, smiling, universally welcomed as she always is. And then came Miss Charlotte Marsh with the colours, holding her place by the right of martyrdom; and then Miss Annan Bryce, a beautiful, militant Joan of Arc; and then the splendid little group of New Crusaders. They all formed a glorious heraldry…

Mrs Despard at its head (of the Women's Freedom League delegation), certainly one of the most conspicuous personalities in the demonstration, was recognised and acclaimed by all classes, but especially by the poor, and no man in the Procession seemed so widely known as Mr. Lansbury…

One episode stands out conspicuous in everyone's memory during the long hours of that march. It was when, in passing the Green Park, when at last I saw the banners of the Men's Political Union bringing up the rear. The Men's League was remarkably strong, numbering some hundreds, and including Mr Zangwill and Mr. A. J. Webbe as first-rate representatives of literature and sport. As I had been instructed I fell in at the head of the Men's Political Union to carry their colours for the rest of the march. Five years ago I had never supposed that I should one day advance down Piccadilly on horseback carrying a huge flag of purple, white and green resting on one shoulder or raised high above my head.

(5) The Sporting Times (15th May 1920)

Miss Jennings is happier in the delineation of character than in the evolution of situations, and the characters in Husbands for All are not flesh and blood, but the puppets of machine-made farce. Still, the first night audience did laugh a good deal. The Little Company is an attractive one in this piece, especially the ladies. Wonderful promise was shown by fetching little Edna Best in an absurd part, but Dorothy Minto (in trousers) is none too well-suited as an impossible domestic servant. Malcolm Cherry (unpardonably fluffy at the premiere), Campbell Gullan, Doris Lytton and Margery Bryce also figured prominently in the excellent cast.

(6) The Common Cause (10th September 1920)

There was some good pieces in Miss Lilian Braithwaite's acting of Mrs. Westonbury, but the part was badly written and the general effect unpleasant. Miss Emily Brooke was a pleasant enough prude, fair, placid, and well favoured, though a trifle slow. She was a brave woman to have "Masters" as parlourmaid. A more alarming domestic than Miss Margery Bryce can hardly be imagined. Her beetle-browed elegance and icy propriety must be more alarming to visitors and owner alike than an enraged bulldog.

(7) The Stage (18th February 1932)

In the dialogue Tatiana is spoken of as a child, of innocent simplicity, living in a fairy world. But at the Faculty the part was sustained with emotional force, rather on tragedy-queen lines by Miss Margery Bryce, an elegant and graceful woman, but by no means a child."

(8) The Worthing Herald (28th September 1951)

On her own confession Nancy Price adds 31 years to her age to play the celebrated 101-year-old matriarch of Whiteoaks, at the Connaught this week…

Margery Bryce, one of the original Whiteoaks company, is all whalebone and indignation as Aunt Augusta, and a piece of character acting to match is the old maidish dithering of Reginald Long's Uncle Ernest.