Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers, the son of Jay Chambers, an artist, was born in Philadelphia on 1st April, 1901. When he was a child the family moved to Long Island. His father lost his job with the New York World: "The news camera and the newsphoto began to replace the staff artist on the newspapers.

His parents divorced and his brother committed suicide. "My brother was lying with his head in the gas oven, his body partly supported by the open door. He had made himself as comfortable as he could. There was a pillow in the oven under his head. His feet were resting on a pile of books set on a kitchen chair. One of his arms hung down rigid. Just below the fingers, on the floor, stood an empty quart whisky bottle." (1)

After leaving secondary school Whittaker Chambers did a variety of menial jobs before enrolling as a day student at Columbia University. He became very interested in poetry and he became friendly with Louis Zukofsky, Guy Endore and Lionel Trilling. In 1924, Chambers began reading the works of Lenin. According to his biographer, Sam Tanenhaus, he was attracted to his authoritarianism and he "had at last found his church." (2)

Kathryn S. Olmsted, the author of Red Spy Queen (2002): "Many adjectives can be used to describe.... Whittaker Chambers: he was brilliant, disturbed, idealistic, disfunctional. At Columbia, which he attended in the 1920s, his professors recognized him as a talented writer and an outstanding intellect - but also as a rogue. He went on destructive drinking binges; he let his teeth decay into blackened stumps; he struggled to overcome his homosexual tendencies by launching numerous affairs with women; and he wrote a play about Jesus Christ that the university's administrators found blasphemous. At first suspended, he was then barred from ever attending Columbia again." (3)

American Communist Party

Chambers joined the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and worked as a journalist for several left-wing publications. In July 1927 he became a member of the staff of the Daily Worker. Other contributors included Richard Wright, Howard Fast, John Gates, Louis Budenz, Michael Gold, Jacob Burck, Sandor Voros, William Patterson, Maurice Becker, Benjamin Davis, Edwin Rolfe, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Robert Minor, Fred Ellis, William Gropper, Lester Rodney, David Karr, John L. Spivak and Woody Guthrie. At its peak, the newspaper achieved a circulation of 35,000. Chambers also briefly edited the New Masses. (3)

Chambers became critical of the main tone of articles that appeared in these left-wing journals: "It occurred to me that…I might by writing, not political polemics which few people ever wanted to read, but stories that anybody might want to read - stories in which the correct conduct of the Communist would be shown and without political comment.” The historian, Kathryn S. Olmsted, has argued that he "eventually became known as one of the Party's most effective propagandists. Ironically, though, just as his literary career was taking off, the Party decided it had a new job for him." (4)

In 1932 Whittaker Chambers, on the orders of the Communist Party of the United States leadership, officially dropped out of politics and went "underground". He became a full-time, salaried agent of the Soviet secret police. Over the next two years Chambers worked for Soviet military intelligence, the Foreign Section of the GPU, in New York City. (5) "During the six years that I worked underground, nobody ever told me what service I had been recruited into, and as a disciplined Communist, I never asked." (6)

The Ware Group

Harold Ware, the son of Ella Reeve Bloor, was a member of the Communist Party of the United States and a consultant to the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). Ware established a "discussion group" that included Alger Hiss, Nathaniel Weyl, Laurence Duggan, Harry Dexter White, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Henry H. Collins, Lee Pressman and Victor Perlo. Ware was working very close with Joszef Peter, the "head of the underground section of the American Communist Party." It was claimed that Peter's design for the group of government agencies, to "influence policy at several levels" as their careers progressed". Weyl later recalled that every member of the Ware Group was also a member of the CPUSA: "No outsider or fellow traveller was ever admitted... I found the secrecy uncomfortable and disquieting." (7)

Whittaker Chambers was a key figure in the Ware Group: "The Washington apparatus to which I was attached led its own secret existence. But through me, and through others, it maintained direct and helpful connections with two underground apparatuses of the American Communist Party in Washington. One of these was the so-called Ware group, which takes its name from Harold Ware, the American Communist who was active in organizing it. In addition to the four members of this group (including himself) whom Lee Pressman has named under oath, there must have been some sixty or seventy others, though Pressman did not necessarily know them all; neither did I. All were dues-paying members of the Communist Party. Nearly all were employed in the United States Government, some in rather high positions, notably in the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Justice, the Department of the Interior, the National Labor Relations Board, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Railroad Retirement Board, the National Research Project - and others." (8)

Susan Jacoby, the author of Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009), has pointed out: "Hiss's Washington journey from the AAA, one of the most innovative agencies established at the outset of the New Deal, to the State Department, a bastion of traditionalism in spite of its New Deal component, could have been nothing more than the rising trajectory of a committed careerist. But it was also a trajectory well suited to the aims of Soviet espionage agents in the United States, who hoped to penetrate the more traditional government agencies, like the State, War, and Treasury Departments, with young New Dealers sympathetic to the Soviet Union (whether or not they were actually members of the Party). Chambers, among others, would testify that the eventual penetration of the government was the ultimate aim of a group initially overseen in Washington by Hal Ware, a Communist and the son of Mother Bloor... When members did succeed in moving up the government ladder, they were supposed to separate from the Ware organization, which was well known for its Marxist participants. Chambers was dispatched from New York by underground Party superiors to supervise and coordinate the transmission of information and to ride herd on underground Communists - Hiss among them - with government jobs." (9)

Boris Bykov

In the summer of 1936, Joszef Peter introduced Chambers to Boris Bykov. According to Sam Tanenhaus, the author of Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997): "Bykov, about forty years old and Chambers's own height, was turned out neatly in a worsted suit. He wore a hat, in part to cover his hair, which was memorably red. He gave in fact an overall impression of redness. His lashes were ginger-colored, his eyes an odd red-brown, and his complexion was ruddy.... He also was subject to violent mood swings, switching from ferocious tantrums to grating fits of false jollity. And he was habitually distrustful. Time and again he questioned Chambers sharply on his ideological views and about his previous underground activities." (10)

Chambers wrote in Witness (1952): " When I was with Colonel Bykov, I was not master of my movements. Most of our meetings took place in New York City. We always prearranged them a week or ten days ahead. As a rule, we first met in a movie house. I would go in and stand at the back. Bykov, who nearly always had arrived first, would get up from the audience at the agreed time and join me. We would go out together. Bykov, not I, would decide what route we should then take in our ramblings (we usually walked several miles about the city). We would wander at night, far out in Brooklyn or the Bronx, in lonely stretches of park or on streets where we were the only people." (11)

Chambers questioned Colonel Bykov about the Great Purge that was taking place in the Soviet Union but it was clear that he completely supported the policies of Joseph Stalin. "Like every Communist in the world, I felt its backlash, for the Purge also swept through the Soviet secret apparatuses. I underwent long hours of grilling by Colonel Bykov in which he tried, without the flamboyance, but with much of the insinuating skill of Lloyd Paul Stryker, the defense lawyer in the first Hiss trial, to prove that I had been guilty of Communist heresies in the past, that I was secretly a Trotskyist, that I was not loyal to Comrade Stalin. I emerged unharmed from those interrogations, in part because I was guiltless, but more importantly, because Colonel Bykov had begun to regard me as indispensable to his underground career." (12)

Soviet Spy Network

In December 1936 Bykov asked Chambers for names of people who would be willing to supply the Soviets with secret documents. (13) Chambers selected Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Julian Wadleigh and George Silverman. Bykov suggested that the men must be "put in a productive frame of mind" with cash gifts. Chambers argued against this policy as they were "idealists". Bykov was adamant. The handler must always have some kind of material hold over his asset: "Who pays is the boss, and he who accepts money must give something in return." (14)

Chambers was given $600 with which to purchase "Bokhara rugs, woven in one of the Asian Soviet republics and coveted by collectors". (15) Chambers recruited his friend, Meyer Schapiro, to buy carpets at an Armenian wholesale establishment on lower Fifth Avenue. Cambers then arranged for the four men to be interviewed by Bykov in New York City. The men agreed to work as Soviet agents. They were reluctant to take the gifts. Wadleigh said that he wanted nothing more than to do "something practical to protect mankind from its worst enemies." (16)

With the recruitment of the four agents, Chambers's underground work, and his daily routine, now centred on espionage. "In the case of each contact he had first to arrange a rendezvous, in rare instances at the contact's house, more commonly at a neutral site (street corner, park, coffee shop) in Washington. On the appointed day Chambers drove down from New Hope (a distance of 110 miles) and was handed a small batch of documents (at most twenty pages), which he slipped into a slim briefcase." (17)

Alger Hiss was the most productive of Bykov's agents. According to G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004): Hiss was so productive in bringing home documents that he precipitated a further change in the Soviets's methods for obtaining them... Chambers, however, only visited Hiss about once a week, since his practice was to round up documents from his sources, have them photocopied and returned, and take the photocopies to New York only at weekly intervals. In order to continue this practice, but protect Hiss, Bykov instructed Hiss to type copies of the documents himself and retain them for Chambers." (18)

Whittaker Chambers, later admitted in Witness (1952): "It was Alger Hiss's custom to bring home documents from the State Department approximately once a week or once in ten days. He would bring out only the documents that happened to cross his desk on that day, and a few that on one pretext or another he had been able to retain on his desk. Bykov wanted more complete coverage. He proposed that the (Lawyer - the Soviets's code name for Hiss at the time) should bring home a briefcase of documents every night." (19)

Joseph Stalin

Chambers, like most members of the Communist Party of the United States supported the policies of Joseph Stalin. In the summer of 1932 Stalin became aware that opposition to his policies were growing. Some party members were publicly criticizing Stalin and calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Sergey Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

On 1st December, 1934, Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev. Stalin claimed that Nikolayev was part of a larger conspiracy led by Leon Trotsky against the Soviet government. (20) This resulted in the arrest and trial in August, 1936, of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin. All were found guilty and executed.

Juliet Poyntz

Whittaker Chambers began to privately question the policies of Stalin. So also did his friend and fellow spy, Juliet Poyntz. In 1936 she spent time in Moscow and was deeply shocked by the purge that was taking place of senior Bolsheviks. Unconvinced by the Show Trials she returned to the United States as a critic of the rule of Joseph Stalin. As fellow member, Benjamin Gitlow, pointed out: "She (Juliet Poyntz) saw how men and women with whom she had worked, men and women she knew were loyal to the Soviet Union and to Stalin, were sent to their doom." (21)

It has been argued by Ted Morgan, the author of Reds: McCarthyism in Twenty-Century America (2003) that "Juliet Poyntz.. got caught up in party factions, she had the distinction of giving her name to an 'ism,' when the Daily Worker called for the liquidation of Poyntzism." In May 1937, Carlo Tresca, later recalled that "she confided in me that she could no longer approve of things under the Stalin regime." (22)

Juliet Poyntz was reported missing in June, 1937. Whittaker Chambers claimed in Witness (1952): "She was living in a New York hotel. One evening she left her room with the light burning and a page of unfinished handwriting on the table. She was never seen again. It is known that she went to meet a Communist friend in Central Park and that he had decoyed her there as part of a G.P.U. trap. She was pushed into an automobile and two men drove her off. The thought of this intensely feminine woman, coldly murdered by two men, sickened me in a physical way, because I could always see her in my mind's eye." (23)

On 8th February, 1938, The New York Times ran a story, quoting Carlo Tresca, that Juliet Poyntz had been lured or kidnapped to Soviet Russia by a prominent Communist... connected with the secret police in Moscow, sent to this country for that purpose". Tresca claimed that the case was similar to that of Ignaz Reiss: "Poyntz was a marked person, similar to have disillusioned Bolsheviks." (24) Another source said that she had been murdered because she was planning to write a book that was highly critical of Joseph Stalin and would tell of her time in the "underground". (25)

Chambers asked Boris Bykov what had happened to Juliet Poyntz. He replied: "Gone with the wind". Chambers commented: "Brutality stirred something in him that at its mere mention came loping to the surface like a dog to a whistle. It was as close to pleasure as I ever saw him come. Otherwise, instead of showing pleasure, he gloated. He was incapable of joy, but he had moments of mean exultation. He was just as incapable of sorrow, though he felt disappointed and chagrin. He was vengeful and malicious. He would bribe or bargain, but spontaneous kindness or generosity seemed never to cross his mind. They were beyond the range of his feeling. In others he despised them as weaknesses." (26). As a result of this conversation, Chambers decided to stop working for the Communist Party of the United States.

Issac Don Levine

After the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, Chambers decided to take action: "Two days after Hitler and Stalin signed their pact - I went to Washington and reported to the authorities what I knew about the infiltration of the United States Government by Communists. For years, international Communism, of which the United States Communist Party is an integral part, had been in a state of undeclared war with this Republic. With the Hitler-Stalin pact that war reached a new stage. I regarded my action in going to the Government as a simple act of war, like the shooting of an armed enemy in combat." (27)

In 1939, Chambers met the journalist, Isaac Don Levine. Chambers told Levine that there was a communist cell in the United States government. Chambers recalled in his book, Witness (1952): "For years, he (Levine) has carried on against Communism a kind of private war which is also a public service. He is a skillful professional journalist and a notable ghost writer... From the first, Levine had urged me to take my story to the proper authorities. I had said no. I was extremely wary of Levine. I knew little or nothing about him, and the ex-Communist Party, but the natural prey of anyone who can turn his plight to his own purpose or profit." (28)

In April 1939 Chambers joined Time Magazine as a book and film reviewer. It soon became clear that Chambers was a strong anti-communist and this reflected the views of the owner of the magazine, Henry Luce, who arranged for him to be promoted to senior editor. Later that year he joined the group that determined editorial policy. Chambers wrote in his memoirs: "My debt and my gratitude to Time cannot be measured. At a critical moment, Time gave me back my life.

Chambers now bought a farm in Westminster, Maryland, and became a Quaker: "I returned to the land as a way of bringing up my children in close touch with the soil and hard work, and apart from what I consider the false standards and vitiating influence of the cities."

Water Krivinsky

Chambers met Walter Krivitsky after he published an article on Joseph Stalin in the Saturday Evening Post. Chambers later recalled in Witness (1952): "I met Krivitsky with extreme reluctance. Long after my break with the Communist Party, I could not think of Communists or Communism without revulsion. I did not wish to meet even ex-Communists. Toward Russians, especially, I felt an organic antipathy. But one night, when I was at Levine's apartment in New York, Krivitsky telephoned that he was coming over. There presently walked into the room a tidy little man about five feet six with a somewhat lined gray face out of which peered pale blue eyes. They were professionally distrustful eyes, but oddly appealing and wistful, like a child whom life has forced to find out about the world, but who has never made his peace with it. By way of handshake, Krivitsky touched my hand. Then he sat down at the far end of the couch on which I also was sitting. His feet barely reached the floor. I turned to look at him. He did not look at me. He stared straight ahead." (29)

Krivitsky's biographer, Gary Kern, claims that he was not at first impressed with Chambers: "Krivitsky saw Chambers as a big slob. From childhood, unhappy with his bulky body and shabby, hand-me-down clothes, he had made a point of dressing badly as a private protest against the fortunately born... Everything about Chambers was disorderly, except his mind." Isaac Don Levine had once described "Chambers as looking like a plumber's helper on a repair mission... His clothes were rumpled, his short figure chunky, his teeth unsightly and his gait lumbering."

Krivitsky said that the Kronstadt Uprising was the turning point. "But who else for a thousand miles around could know what we were talking about? Here and there, some fugitive in a dingy room would know. But, as Krivitsky and I looked each other over, it seemed to me that we were like two survivors from another age of the earth, like two dated dinosaurs, the last relics of the revolutionary world that had vanished in the Purge. Even in that vanished world, we had been a special breed - the underground activists. There were not many of our kind left alive who still spoke the language that had also gone down in the submergence. I said, yes, Kronstadt had been the turning point.... Kronstadt is a naval base a few miles west of Leningrad in the Gulf of Finland. From Kronstadt during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the sailors of the Baltic Fleet had steamed their cruisers to aid the Communists in capturing Petrograd. Their aid had been decisive. They were the sons of peasants. They embodied the primitive revolutionary upheaval of the Russian people. They were the symbol of its instinctive surge for freedom. And they were the first Communists to realize their mistake and the first to try to correct it. When they saw that Communism meant terror and tyranny, they called for the overthrow of the Communist Government and for a time imperiled it. They were bloodily destroyed or sent into Siberian slavery by Communist troops led in person by the Commissar of War, Leon Trotsky, and by Marshal Tukhachevsky, one of whom was later assassinated, the other executed, by the regime they then saved."

The two men talked all night. Chambers recalled that Walter Krivitsky said at one point: "Looked at concretely, there are no ex-Communists. There are only revolutionists and counter revolutionists." Chambers interpreted that these words "meant that, in the 20th century, all politics, national and international, is the politics of revolution - that, in sum, the forces of history in our time can be grasped only as the interaction of revolution and counterrevolution." Both men dismissed the importance of conservatives: "Is merely a conservative, resisting it out of habit and prejudice. He believed, as I believe, that fascism (whatever softening name the age of euphemism chooses to call it by) is inherent in every collectivist form, and that it can be fought only by the force of an intelligence, a faith, a courage, a self-sacrifice, which must equal the revolutionary spirit that, in coping with, it must in many ways come to resemble. No one knows so well as the ex-Communist the character of the conflict, and of the enemy, or shares so deeply the same power of faith and willingness to stake his life on his beliefs. For no other has seen so deeply into the total nature of the evil with which Communism threatens mankind. Counterrevolution and conservatism have little in common. In the struggle against Communism the conservative is all but helpless. For that struggle cannot be fought, much less won, or even understood, except in terms of total sacrifice. And the conservative is suspicious of sacrifice; he wishes first to conserve, above all what he is and what he has." Just before he left Krivitsky said: "In our time, informing is a duty." Chambers agreed and at that point: "I knew that, if the opportunity offered, I would inform." (30)

Adolf Berle

In August 1939, Isaac Don Levine arranged for Chambers to meet Adolf Berle, one of the top aides to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He later wrote in Witness: "The Berles were having cocktails. It was my first glimpse of that somewhat beetle-like man with the mild, intelligent eyes (at Harvard his phenomenal memory had made him a child prodigy). He asked the inevitable question: If I were responsible for the funny words in Time. I said no. Then he asked, with a touch of crossness, if I were responsible for Time's rough handling of him. I was not aware that Time had handled him roughly. At supper, Mrs. Berle took swift stock of the two strange guests who had thus appeared so oddly at her board, and graciously bounced the conversational ball. She found that we shared a common interest in gardening. I learned that the Berles imported their flower seeds from England and that Mrs. Berle had even been able to grow the wild cardinal flower from seed. I glanced at my hosts and at Levine, thinking of the one cardinal flower that grew in the running brook in my boyhood. But I was also thinking that it would take more than modulated voices, graciousness and candle-light to save a world that prized those things." (31)

After dinner Chambers told Berle about government officials spying for the Soviet Union: "Around midnight, we went into the house. What we said there is not in question because Berle took it in the form of penciled notes. Just inside the front door, he sat at a little desk or table with a telephone on it and while I talked he wrote, abbreviating swiftly as he went along. These notes did not cover the entire conversation on the lawn. They were what we recapitulated quickly at a late hour after a good many drinks. I assumed that they were an exploratory skeleton on which further conversations and investigation would be based." (32)

According to Isaac Don Levine the list of "espionage agents" included Alger Hiss, Donald Hiss, Laurence Duggan, Lauchlin Currie, Harry Dexter White, John Abt, Marion Bachrach, Nathan Witt, Lee Pressman, Julian Wadleigh, Noel Field and Frank Coe. Chambers also named Joszef Peter, as being "responsible for the Washington sector" and "after 1929 the "head of the underground section" of the Communist Party of the United States.

Chambers later claimed that Berle reacted to the news with the comment: "We may be in this war within forty-eight hours and we cannot go into it without clean services." John V. Fleming, has argued in The Anti-Communist Manifestos: Four Books that Shaped the Cold War (2009) Chambers had "confessed to Berle the existence of a Communist cell - he did not yet identify it as an espionage team - in Washington." (33) Berle, who was in effect the president's Director of Homeland Security, raised the issue with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, "who profanely dismissed it as nonsense."

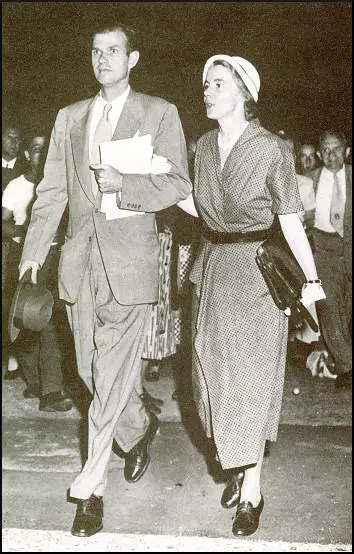

Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss

In 1943 the FBI received a copy of Berle's memorandum. Whittaker Chambers was interviewed by the FBI but J. Edgar Hoover concluded, after being briefed on the interview, that Chambers had little specific information. However, this information was sent to the State Department security officials. One of them, Raymond Murphy, interviewed Chambers in March 1945 about these claims. Chambers now gave full details of Hiss's spying activities. A report was sent to the FBI and in May, 1945, they had another meeting with Chambers.

In August 1945, Elizabeth Bentley walked into an FBI office and announced that she was a former Soviet agent. In a statement she gave the names of several Soviet agents working for the government. This included Harry Dexter White and Lauchlin Currie. Bentley also said that a man named "Hiss" in the State Department was working for Soviet military intelligence. In the margins of Bentley's comments about Hiss, someone at the FBI made a handwritten notation: "Alger Hiss".

The following month, Igor Guzenko, a clerk in the Soviet Embassy in Ottowa, defected to the Canadian authorities. He gave them a large number of documents detailing the existence of a large Soviet military intelligence network in Canada. Guzenko was also interviewed by the FBI. He told them that "the Soviets had an agent in the United States in May 1945 who was an assistant to the secretary of state, Edward R. Stettinius." Alger Hiss was Stettinius's assistant at the time."

The FBI sent a report on Hiss to the Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in November 1946. It concluded that Alger Hiss was probably a Soviet agent. Hiss was interviewed by D.M. Ladd, the FBI's Assistant Director, and denied any associations with Communism. The State Department security officials restricted his access to confidential documents, and the FBI wiretapped his office and home phones.

Dean Acheson came under pressure to sack Hiss. Acheson refused to do this and instead contacted John Foster Dulles, who was on the board of directors of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Dulles arranged for Hiss to become president of the organization. At first Hiss refused to go and said he would rather stay and answer his critics. However, Acheson insisted and suggested that "this is the kind of thing which rarely, if ever, gets cleared up."

House of Un-American Activities Committee

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie, Abraham George Silverman, John Abt, Lee Pressman, Nathan Witt, Henry H. Collins and Donald Hiss. Silverman, Collins, Abt, Pressman and Witt all used the Fifth Amendment defence and refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC. (34)

Chamber's accusations made headline news. Hiss immediately sent a telegram to John Parnell Thomas, HUAC's acting chairman: "I do not know Mr. Chambers, and, so far as I am aware, have never laid eyes on him. There is no basis for the statements about me made to your committee." Hiss asked for the opportunity to "appear... before your committee to make these statements formally and under oath." He also sent a copy of the telegram to John Foster Dulles.

On 5th August, 1948, Hiss appeared before the HUAC: "I am not and never have been a member of the Communist Party. I do not and never have adhered to the tenets of the Communist Party. I am not and never have been a member of any Communist-front organization. I have never followed the Communist Party line, directly or indirectly. To the best of my knowledge, none of my friends is a Communist.... To the best of my knowledge, I never heard of Whittaker Chambers until 1947, when two representatives of the Federal Bureau of investigation asked me if I knew him... I said I did not know Chambers. So far as I know, I have never laid eyes on him, and I should like to have the opportunity to do so."

G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004) has pointed out: "By his categorical disassociation of himself from even the slightest connection with Communism or Communist-front activities, Hiss set in motion a narrative of his career that he would devote the rest of his life to telling and retelling. In that narrative Hiss was simply a young lawyer who had gone to Washington and became committed to the policies of the New Deal and international peace. His career had been a consistent effort to promote those ideals. He had never been a Communist, and those who were accusing him of being such were seeking to scapegoat him for partisan purposes. They were a pack of liars, and he was their intended victim."

Richard Nixon now joined in the controversy. He argued that "while it would be virtually impossible to prove that Hiss was or was not a Communist... the HUAC... should be able to establish by corroborative testimony whether or not the two men knew each other." Nixon now became the head of a subcommittee to pursue the inquiry of Alger Hiss. HUAC called Hiss back for an executive session in New York City. This time he admitted that he did know Whittaker Chambers but at the time he used the name George Crosley. He also agreed with Chambers's testimony that he had rented him an apartment but denied that he was ever a member of the American Communist Party. Hiss added: "May I say for the record at this point that I would like to invite Mr. Whittaker Chambers to make those same statements out of the presence of the committee, without their being privileged for suit for libel. I challenge you to do it, and I hope you will do it damned quickly."

On 17th August, 1948, Chambers repeated his claim that "Alger Hiss was a communist and may be now." He added, "I do not think Mr. Hiss will sue me for slander or libel." At first Hiss hesitated but he realised that if he did not sue Chambers he would be considered guilty of being a communist. After lengthy discussions with several lawyers, Hiss filed a suit against Chambers on 27th September, 1948.

Alger Hiss Perjury Trial

On 15th December, 1948, the grand jury asked Alger Hiss whether he had known Whittaker Chambers after 1936, and whether he had passed copies of any stolen government documents to Chambers. As he had done previously, Hiss answered no to both questions. The grand jury then indicted him on two counts of perjury. The New York Times reported that he "appeared solemn, anxious, and unhappy" with a grim and worried look". It added that to "observers it seemed obvious that he had not expected to be indicted".

The trial began in May 1949. The first piece of evidence concerned a car purchased by Chambers for $486.75 from a Randallstown car dealer on 23rd November, 1937. Chambers claimed that Hiss had given him $400 to buy the car. The prosecution was able to show that on 19th November Hiss had withdrawn $400 from his bank account. Hiss claimed that this was to buy furniture for a new house. But the Hisses had not signed a lease on any house at that time, and could produce no receipts for the furniture.

The main evidence that the prosecution produced consisted of sixty-five pages of re-typed State Department documents, plus four notes in Hiss's handwriting summarizing the contents of State Department cables. Chambers claimed Alger Hiss had given them to him in 1938 and that Priscilla Hiss had retyped them on the Hisses' Woodstock typewriter. Hiss initially denied writing the note, but experts confirmed it was his handwriting. The FBI was also able to show that the documents had been typed on Hiss's typewriter.

In the first trial Thomas Murphy stated that if the jury did not believe Chambers, the government had no case, and, at the end, four jurors remained unconvinced that Chambers had been telling the truth about how he had obtained the typed copies of documents. They thought that somehow Chambers had gained access to Hiss's typewriter and copied the documents. The first trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict.

The second trial began in November 1949. One of the main witnesses against Alger Hiss in the second trial was Hede Massing. She claimed that at a dinner party in 1935 Hiss told her that he was attempting to recruit Noel Field, then an employee of the State Department, to his spy network. Whittaker Chambers claims in Witness (1952) that this was vital information against Hiss: "At the second Hiss trial, Hede Massing testified how Noel Field arranged a supper at his house, where Alger Hiss and she could meet and discuss which of them was to enlist him. Noel Field went to Hede Massing. But the Hisses continued to see Noel Field socially until he left the State Department to accept a position with the League of Nations at Geneva, Switzerland-a post that served him as a 'cover' for his underground work until he found an even better one as dispenser of Unitarian relief abroad.

Alger Hiss wrote in his autobiography, Recollections of a Life (1988): "Throughout the first trial and most of the second, I was confident of acquittal. But as the second trial wore on, I realized that it was no ordinary one. The entire jury of public opinion, all of those from whom my juries had been selected, had been tampered with. Richard Nixon, my unofficial prosecutor, seeking to build his career on getting a conviction in my case, had from the days of the congressional committee hearings constantly issued public statements and leaks to the press against me. There were moments when I was swept with gusts of anger at the prosecutor's bullying tactics with my witnesses and his devious insinuations in place of evidence - tactics that unfortunately are all too common in a prosecutor's bag of tricks... It was almost unbearable to hear the sneers of the prosecutor as he cross-examined my wife and other witnesses."

Hiss was unhappy with the way he was dealt with in court: "When it was my turn to be cross-examined, the ordeal was of a different sort. Here, court procedures are all weighted in favor of the questioner. The witness may not argue or explain. I was able only to answer directly and briefly, however weighted or hostile the question. My lawyer could object to improper questions, but at the risk of letting the jury get the impression that we were reluctant to have the subject explored. But I was at least not forced to remain mutely impassive, and I was confident that later my lawyer could correct false impressions which bullying cross-examination might leave. It was especially in those moments of provocation triggered by false insinuations that anger and fatigue were to be guarded against. I lost my temper at least once and immediately realized I had erred. The etiquette of the bull ring did not permit the tormented to show even annoyance. I sensed that the jury thought the prosecutor must have scored a point if I reacted so sharply."

Chambers wrote about the Hiss case in his book Witness (1952). He wrote: “Like the soldier, the spy stakes his freedom or his life on the chances of action. The informer is different, particularly the ex-Communist informer. He risks little. He sits in security and uses his special knowledge to destroy others. He has that special information to give because he once lived within their confidence, in a shared faith, trusted by them as one of themselves, accepting their friendship, feeling their pleasures and griefs, sitting in their houses, eating at their tables, accepting their kindness, knowing their wives and children. If he had not done these things he would have no use as an informer.... I know that I am leaving the winning side for the losing side, but it is better to die on the losing side than to live under Communism.”

The second jury found Alger Hiss guilty of two counts of perjury and on 25th January, 1950, he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment. The Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was asked later that day about the Hiss trial. He replied: "Mr. Hiss's case is before the courts, and I think it would be highly improper for me to discuss the legal aspects of the case, or the evidence, or anything to do with the case. I take it the purpose of your question was to bring something other than that out of me... I should like to make it clear to you that whatever the outcome of any appeal which Mr. Hiss or his lawyers may take in this case, I do not intend to turn my back on Alger Hiss. I think every person who has known Alger Hiss, or has served with him at any time, has upon his conscience the very serious task of deciding what his attitude is, and what his conduct should be. That must be done by each person, in the light of his own standards and his own principles... My friendship is not easily given, and not easily withdrawn."

Chambers resigned from Time Magazine and worked during the 1950s for Life Magazine, Fortune and the National Review. Chambers wrote to his friend, William Buckley: "I am a man of the Right because I mean to uphold capitalism in its American version. But I claim that capitalism is not, and by its essential nature cannot conceivably be, conservative."

Whittaker Chambers died after suffering a heart-attack at his home in Westminster, Maryland, on 9th July, 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

Like the soldier, the spy stakes his freedom or his life on the chances of action. The informer is different, particularly the ex-Communist informer. He risks little. He sits in security and uses his special knowledge to destroy others. He has that special information to give because he once lived within their confidence, in a shared faith, trusted by them as one of themselves, accepting their friendship, feeling their pleasures and griefs, sitting in their houses, eating at their tables, accepting their kindness, knowing their wives and children. If he had not done these things he would have no use as an informer.

(2) Whittaker Chambers, testimony before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (3rd August, 1948)

I joined the Communist Party in 1924 and left in 1937. For a number of years I had served in the underground, chiefly in Washington. I knew it at its top level, a group of seven or so men, from among whom in later years certain members of Miss Bentley's organization were apparently recruited. Lee Pressman was also a member of this group, as was Alger Hiss, who, as a member of the State Department, later organized the conferences at Dumbarton Oaks, San Francisco, and the United States side of the Yalta Conference.

The purpose of this group at that time was not primarily espionage. Its original purpose was the Communist infiltration of the American Government. But espionage was certainly one of of its eventual objectives. Let no one be surprised at this statement. Disloyalty is a matter of principle with every member of the Communist Party.

(3) William A. Reuben, review of The Secret World of American Communism in the journal Rights (1995).

Chambers had been shown to be inaccurate about almost every detail of his personal life, from when and how he left Columbia University and the New York Public Library to how he made a living, to whether his mother worked, to when he got married and how old his brother was when he committed suicide. More important, he had contradicted his earlier testimony given to the Committee on numerous crucial subjects, from when he joined and left the Communist Party and how long he was in it, to whether he had known Harold Ware, to how and where he first met Alger Hiss. Since he had testified under oath in both instances, it was clear that either he had willfully perjured himself or that he was a man incapable of differentiating truth from fiction.

However, there was one important thing he had remained consistent about, as he had been for the last nine years: he still maintained that whatever he and Hiss did in the underground, espionage was not part of their activities. "Alger Hiss didn't do anything of this character," Chambers said near the close of his examination on November 5. "I never obtained documents from him."

(4) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

I met Krivitsky with extreme reluctance. Long after my break with the Communist Party, I could not think of Communists or Communism without revulsion. I did not wish to meet even ex-Communists. Toward Russians, especially, I felt an organic antipathy.

But one night, when I was at Levine's apartment in New York, Krivitsky telephoned that he was coming over. There presently walked into the room a tidy little man about five feet six with a somewhat lined gray face out of which peered pale blue eyes. They were professionally distrustful eyes, but oddly appealing and wistful, like a child whom life has forced to find out about the world, but who has never made his peace with it. By way of handshake, Krivitsky touched my hand. Then he sat down at the far end of the couch on which I also was sitting. His feet barely reached the floor. I turned to look at him. He did not look at me. He stared straight ahead. Then he asked in German (the only language that we ever spoke): "Is the Soviet Government a fascist government?"

Communists dearly love to begin a conversation with a key question the answer to which will also answer everything else of importance about the answerer. I recognized that this was one of those questions. On the political side, I had broken with the Communist Party in large part because I had become convinced that the Soviet Government was fascist. Yet when I had to give that answer out loud, instead of in the unspoken quiet of my own mind, all the emotions that had ever bound me to Communism rose in a final spasm to stop my mouth. I sat silent for some moments. Then I said: "The Soviet Government is a fascist government." Later on that night, Krivitsky told me that if I had answered yes at once, he would have distrusted me. Because I hesitated, and he felt the force of my struggle, he was convinced that I was sincere.

When I answered slowly, and a little somberly, as later on I sometimes answered questions during the Hiss Case, Krivitsky turned for the first time and looked at me directly. "You are right, and Kronstadt was the turning point."

I knew what he meant. But who else for a thousand miles around could know what we were talking about? Here and there, some fugitive in a dingy room would know. But, as Krivitsky and I looked each other over, it seemed to me that we were like two survivors from another age of the earth, like two dated dinosaurs, the last relics of the revolutionary world that had vanished in the Purge. Even in that vanished world, we had been a special breed - the underground activists. There were not many of our kind left alive who still spoke the language that had also gone down in the submergence. I said, yes, Kronstadt had been the turning point.Kronstadt is a naval base a few miles west of Leningrad in the Gulf of Finland. From Kronstadt during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the sailors of the Baltic Fleet had steamed their cruisers to aid the Communists in capturing Petrograd. Their aid had been decisive. They were the sons of peasants. They embodied the primitive revolutionary upheaval of the Russian people. They were the symbol of its instinctive surge for freedom. And they were the first Communists to realize their mistake and the first to try to correct it. When they saw that Communism meant terror and tyranny, they called for the overthrow of the Communist Government and for a time imperiled it. They were bloodily destroyed or sent into Siberian slavery by Communist troops led in person by the Commissar of War, Leon Trotsky, and by Marshal Tukhachevsky, one of whom was later assassinated, the other executed, by the regime they then saved.

Krivitsky meant that by the decision to destroy the Kronstadt sailors, and by its cold-blooded action in doing so, Communism had made the choice that changed it from benevolent socialism to malignant fascism. Today, I could not answer, yes, to Krivitsky's challenge. The fascist character of Communism was inherent in it from the beginning. Kronstadt changed the fate of millions of Russians. It changed nothing about Communism. It merely disclosed its character.

Krivitsky and I began to talk quickly as if we were racing time. Levine first dozed in his chair, and then, around midnight, went to bed. About three o'clock in the morning, he came down in his bathrobe, found us still talking and went back to bed. Day dawned. Krivitsky and I went out to a cafeteria near the corner of 59th Street and Lexington Avenue. We were still talking there at eleven o'clock that morning. We parted because we could no longer keep our eyes open.

We talked about Krivitsky's break with Communism and his flight with his wife and small son from Amsterdam to Paris. We talked about the attempts of the G.P.U. to trap or kill him in Europe and the fact that he had not been in the United States 3 week before the Russian secret police set a watch over his apartment. We talked about the murder of Ignatz Reiss, the Soviet agent whose break from the Communist Party in Switzerland had precipitated Krivitsky's. They had been friends. The G.P.U. had demanded that Krivitsky take advantage of his friendship to trap or kill Reiss.

That night, too, I learned the name of Boris Bykov and that Herman's real name had been Valentine Markin, and why he had been murdered and by whom.

But nothing else that we said was so important for the world, or for the course of action that it enjoined upon us both in our different ways, as what Krivitsky had to tell me about the designs of Soviet foreign policy. For it was then that I first learned that, for more than a year, Stalin had been desperately seeking to negotiate an alliance with Hitler. Attempts to negotiate the pact had been made throughout the period when Communism (through its agency, the Popular Front) was posing to the masses of mankind as the only inflexible enemy of fascism. As, in response to my first incredulity, Krivitsky developed the political logic that necessitated the alliance, I knew at once, as only an ex-Communist would, that he was speaking the truth. The alliance was, in fact, a political inevitability. I wondered only what blind spot had kept me from foreseeing it. For, by means of the pact, Communism could pit one sector of the West against the other, and use both to destroy what was left of the non-Communist world. As Communist strategy, the pact was thoroughly justified, and the Communist Party was right in denouncing all those who opposed it as Communism's enemies. From any human point of view, the pact was evil.

We passed naturally to the problem of the ex-Communist and what he could do against that evil. Krivitsky did not then, or at any later time, tell me what he himself had done or would do. It was from others that I learned the details of his co-operation with the British Government.

But Krivitsky said one or two things that were to take root in my mind and deeply to influence my conduct, for they seemed to correspond to the reality of my position. He said at one point: "Looked at concretely, there are no ex-Communists. There are only revolutionists and counter revolutionists." He meant that, in the 20th century, all politics, national and international, is the politics of revolution - that, in sum, the forces of history in our time can be grasped only as the interaction of revolution and counterrevolution. He meant that, in so far as a man ventures to think or act politically, or even if he tries not to think or act at all, history will, nevertheless, define what he is in the terms of those two mighty opposites. He is a revolutionist or he is a counter revolutionist. In action there is no middle ground. Nor did Krivitsky suppose, as we discussed then (and later) in specific detail, that the revolution of our time is exclusively Communist, or that the counter revolutionist. is merely a conservative, resisting it out of habit and prejudice. He believed, as I believe, that fascism (whatever softening name the age of euphemism chooses to call it by) is inherent in every collectivist form, and that it can be fought only by the force of an intelligence, a faith, a courage, a self-sacrifice, which must equal the revolutionary spirit that, in coping with, it must in many ways come to resemble. No one knows so well as the ex-Communist the character of the conflict, and of the enemy, or shares so deeply the same power of faith and willingness to stake his life on his beliefs. For no other has seen so deeply into the total nature of the evil with which Communism threatens mankind. Counterrevolution and conservatism have little in common. In the struggle against Communism the conservative is all but helpless. For that struggle cannot be fought, much less won, or even understood, except in terms of total sacrifice. And the conservative is suspicious of sacrifice; he wishes first to conserve, above all what he is and what he has.

(5) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

Unexpectedly, Levine provided the opportunity. Between the time that he proposed to arrange a conversation with the President, and the time I next saw Levine, some months had elapsed. I had gone to work for Time magazine. I was much too busy trying to learn my job to think of Levine, the President or anything else.

Then, on the morning of September 2, 1939, a few days after the Nazi-Communist Pact was signed, and the German armor had rushed on Warsaw, Isaac Don Levine appeared at my office at Time. He explained that he had been unable to arrange to see the President. But he had arranged a substitute meeting with Adolf Berle, the Assistant Secretary of State in charge of security. It was for eight o'clock that night. Would I go?

I hesitated. I did not like the way in which I was presented with an accomplished fact. But "looked at concretely, there are no ex-Communists; there are only revolutionists and counter-revolutionists"; "in our time, informing is a duty." In fact, I was grateful to Levine for presenting me with a decision to which I had only to assent, but which involved an act so hateful that I should have hesitated to take the initiative myself.

I said that I would meet Levine in Washington that night.

The plane was late. Levine was waiting for me nervously in front of the Hay-Adams House. No doubt, he thought that I might have changed my mind, leaving him with nothing to take to Adolf Berle but embarrassing explanations.

Berle was living in Secretary of War Stimson's house. It stood on Woodley Road near Connecticut Avenue. It stood deep in shaded grounds, somewhat jungle like at night. For some reason the cab driver let us out at the entrance to the drive and, as we straggled up to the house, I realized that we were only four or five blocks from the apartment on 28th Street where I had first talked to Alger Hiss. With a wince, I thought of his remark when I told him that

I had taken a job in the Government: "I suppose that you'll turn up next in the State Department."The Berles were having cocktails. It was my first glimpse of that somewhat beetle-like man with the mild, intelligent eyes (at Harvard his phenomenal memory had made him a child prodigy). He asked the inevitable question: If I were responsible for the funny words in Time. I said no. Then he asked, with a touch of crossness, if I were responsible for Time's rough handling of him. I was not aware that Time had handled him roughly.

At supper, Mrs. Berle took swift stock of the two strange guests who had thus appeared so oddly at her board, and graciously bounced the conversational ball. She found that we shared a common interest in gardening. I learned that the Berles imported their flower seeds from England and that Mrs. Berle had even been able to grow the wild cardinal flower from seed. I glanced at my hosts and at Levine, thinking of the one cardinal flower that grew in the running brook in my boyhood. But I was also thinking that it would take more than modulated voices, graciousness and candle-light to save a world that prized those things.

After the coffee, Mrs. Berle left us. Berle, Levine and I went out on the lawn. Three anticipatory chairs were waiting for us, like a mushroom ring in a pasture. The trees laid down islands of shadow, and about us washed the ocean of warm, sweet, southern air whose basic scent is honeysuckle. From beyond, came the rumor of the city, the softened rumble of traffic on Connecticut Avenue.

We had scarcely sat down when a Negro serving man brought drinks. I was intensely grateful. I drank mine quickly. I knew that two or three glasses of Scotch and soda would give me a liberating exhilaration. For what I had to do, I welcomed any aid that would loosen my tongue.

Levine made some prefatory statement about my special information, which, of course, they had already discussed before. Berle was extremely agitated. "We may be in this war within forty-eight hours," he said, "and we cannot go into it without clean services." He said this not once, but several times. I was astonished to hear from an Assistant Secretary of State that the Government considered it possible that the United States might go into the war at once.

Gratefully, I felt the alcohol take hold. It was my turn to speak. I remember only that I said that I was about to give very serious information touching certain people in the Government, but that I had no malice against those people. I believed that they constituted a danger to the country in this crisis. I begged, if possible, that they might merely be dismissed from their posts and not otherwise prosecuted. Even while I said it, I supposed that it was a waste of breath. But it was such a waste of breath as a man must make. I did not realize that it was also supremely ironic. "I am a lawyer, Mr. Chambers," said Mr. Berle, "not a policeman."

It was a rambling talk. I do not recall any special order in it. Nor do I recall many details. I recall chiefly the general picture I drew of Communist infiltration of the Government and one particular point. In view of the war danger, and the secrecy of the bombsight, I more than once stressed to Berle the importance of getting Reno as quickly as possible out of the Aberdeen Proving Ground. (When the F.B.I. looked for him in 1948, he was still employed there.)

We sat on the lawn for two or three hours. Almost all of that time I was talking. I supposed, later on, that I had given Berle the names of Bykov and the head of the steel experimental laboratory. They do not appear in the typed notes. Levine remembers that we discussed micro film. I have no independent recollection of that. But, while we must have covered a good deal of ground in two or three hours, it is scarcely strange that none of us should have remembered too clearly just what he said on the lawn, for most of the time we were holding glasses in our hands.

Around midnight, we went into the house. What we said there is not in question because Berle took it in the form of penciled notes. Just inside the front door, he sat at a little desk or table with a telephone on it and while I talked he wrote, abbreviating swiftly as he went along. These notes did not cover the entire conversation on the lawn. They were what we recapitulated quickly at a late hour after a good many drinks. I assumed that they were an exploratory skeleton on which further conversations and investigation would be based.

After midnight, Levine and I left. As we went out, I could see that Mrs. Berle had fallen asleep on a couch in a room to my right. Adolf Berle, in great excitement, was on the telephone even before we were out the door. I supposed that he was calling the White House.

In August, 1948, Adolf A. Berle testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities not long after my original testimony about Alger Hiss and the Ware Group. The former Assistant Secretary of State could no longer clearly recall my conversation with him almost a decade before. His memory had grown dim on a number of points. He believed, for example, that I had described to him a Marxist study group whose members were not Communists. In any case, he had been unable to take seriously, in 1939, any "idea that the Hiss boys and Nat Witt were going to take over the Government."

At no time in our conversation can I remember anyone's mentioning the ugly word espionage. But how well we understood what we were talking about, Berle was to make a matter of record. For when, four years after that memorable conversation, his notes were finally taken out of a secret file and turned over to the F.B.I., it was found that Adolf Berle himself had headed them: Underground Espionage Agent.