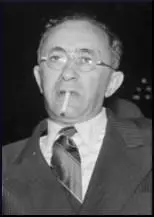

Abraham George Silverman

Abraham George Silverman was born on 2nd February, 1900. He studied at Harvard University and became active in student politics. Silverman joined the Communist Party of the United States.

Silverman supported Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 Presidential Election. In 1933 he was employed by the Railroad Retirement Board in Washington. Soon afterwards be began associating with other radical members of the New Deal administration. This included Harold Ware, Alger Hiss, Nathaniel Weyl, Laurence Duggan, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Henry H. Collins, Lee Pressman and Victor Perlo.

Abraham George Silverman and Ware Group

Whittaker Chambers was a key figure in the Ware Group: "The Washington apparatus to which I was attached led its own secret existence. But through me, and through others, it maintained direct and helpful connections with two underground apparatuses of the American Communist Party in Washington. One of these was the so-called Ware group, which takes its name from Harold Ware, the American Communist who was active in organizing it. In addition to the four members of this group (including himself) whom Lee Pressman has named under oath, there must have been some sixty or seventy others, though Pressman did not necessarily know them all; neither did I. All were dues-paying members of the Communist Party. Nearly all were employed in the United States Government, some in rather high positions, notably in the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Justice, the Department of the Interior, the National Labor Relations Board, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Railroad Retirement Board, the National Research Project - and others." (1)

Susan Jacoby, the author of Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009), has pointed out: "Hiss's Washington journey from the AAA, one of the most innovative agencies established at the outset of the New Deal, to the State Department, a bastion of traditionalism in spite of its New Deal component, could have been nothing more than the rising trajectory of a committed careerist. But it was also a trajectory well suited to the aims of Soviet espionage agents in the United States, who hoped to penetrate the more traditional government agencies, like the State, War, and Treasury Departments, with young New Dealers sympathetic to the Soviet Union (whether or not they were actually members of the Party). Chambers, among others, would testify that the eventual penetration of the government was the ultimate aim of a group initially overseen in Washington by Hal Ware, a Communist and the son of Mother Bloor... When members did succeed in moving up the government ladder, they were supposed to separate from the Ware organization, which was well known for its Marxist participants. Chambers was dispatched from New York by underground Party superiors to supervise and coordinate the transmission of information and to ride herd on underground Communists - Hiss among them - with government jobs." (2)

According to Kathryn S. Olmsted, the author of Red Spy Queen (2002), "Silverman was... one of the most active and difficult members of the group... This bright, mercurial Harvard graduate had been involved in the Communist underground... A heavy, broad-shouldered man with thick glasses and untidy hair, he seemed brilliant but odd to his co-workers. Some of his fellow Communists thought he was offensive, indiscreet, and insufferably dogmatic." (3)

Soviet Spy

In the summer of 1936, Joszef Peter introduced Whittaker Chambers to Boris Bykov. According to Sam Tanenhaus, the author of Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997): "Bykov, about forty years old and Chambers's own height, was turned out neatly in a worsted suit. He wore a hat, in part to cover his hair, which was memorably red. He gave in fact an overall impression of redness. His lashes were ginger-colored, his eyes an odd red-brown, and his complexion was ruddy.... He also was subject to violent mood swings, switching from ferocious tantrums to grating fits of false jollity. And he was habitually distrustful. Time and again he questioned Chambers sharply on his ideological views and about his previous underground activities." (4)

In December 1936 Bykov asked Chambers for names of people who would be willing to supply the Soviets with secret documents. (5) Chambers selected George Silverman, Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, and Julian Wadleigh. Bykov suggested that the men must be "put in a productive frame of mind" with cash gifts. Chambers argued against this policy as they were "idealists". Bykov was adamant. The handler must always have some kind of material hold over his asset: "Who pays is the boss, and he who accepts money must give something in return." (6)

Chambers was given $600 with which to purchase "Bokhara rugs, woven in one of the Asian Soviet republics and coveted by collectors". (7) Chambers recruited his friend, Meyer Schapiro, to buy carpets at an Armenian wholesale establishment on lower Fifth Avenue. Cambers then arranged for the four men to be interviewed by Bykov in New York City. The men agreed to work as Soviet agents. They were reluctant to take the gifts. Wadleigh said that he wanted nothing more than to do "something practical to protect mankind from its worst enemies." (8)

Whittaker Chambers

With the recruitment of the four agents, Chambers's underground work, and his daily routine, now centred on espionage. "In the case of each contact he had first to arrange a rendezvous, in rare instances at the contact's house, more commonly at a neutral site (street corner, park, coffee shop) in Washington. On the appointed day Chambers drove down from New Hope (a distance of 110 miles) and was handed a small batch of documents (at most twenty pages), which he slipped into a slim briefcase." (9)

Whittaker Chambers began to privately question the policies of Joseph Stalin. So also did his friend and fellow spy, Juliet Poyntz. In 1936 she spent time in Moscow and was deeply shocked by the purge that was taking place of senior Bolsheviks. Unconvinced by the Show Trials she returned to the United States as a critic of the rule of Joseph Stalin. As fellow member, Benjamin Gitlow, pointed out: "She (Juliet Poyntz) saw how men and women with whom she had worked, men and women she knew were loyal to the Soviet Union and to Stalin, were sent to their doom." (10)

Chambers asked Boris Bykov what had happened to Juliet Poyntz. He replied: "Gone with the wind". Chambers commented: "Brutality stirred something in him that at its mere mention came loping to the surface like a dog to a whistle. It was as close to pleasure as I ever saw him come. Otherwise, instead of showing pleasure, he gloated. He was incapable of joy, but he had moments of mean exultation. He was just as incapable of sorrow, though he felt disappointed and chagrin. He was vengeful and malicious. He would bribe or bargain, but spontaneous kindness or generosity seemed never to cross his mind. They were beyond the range of his feeling. In others he despised them as weaknesses." (11). As a result of this conversation, Chambers decided to stop working for the Communist Party of the United States.

Chambers decided to tell Silverman about his decision. "Silverman also knew nothing about my break. He was in no way suspicious of me. He told me that the espionage operation was still in full swing, only there were new faces. George was frankly happy to see me again and in the warm glow of his welcome, I felt my purpose go soft. Nothing could have hardened it so quickly as his news about the apparatus. He told me, further, that in a day or two, he was meeting his new contact man, a Russian with a pseudonym that Silverman mentioned... but which I have forgotten. He was meeting the Russian in a drug store near Thomas Circle." (12)

Chambers returned a few days later. By this time Silverman had been told by the new Soviet agent about Chambers defection: "A week or so later, I again walked unannounced into George Silverman's office at the Railroad Retirement Board. This time he looked terrified. Again he hurried me downstairs. 'What has happened?' he asked in a frightened voice. 'What has happened? When I gave (the Soviet agent) your message, he jumped up from the table and grabbed his hat."

Whittaker Chambers told Silverman that he intended to tell the authorities about the Soviet spy network: "Silverman was a slight, nervous little man. But he lacked a pushing quality that I disliked in White. He aroused a protective feeling. For, in fact, he was a child, and the effort that it cost him to be a man was apparent in the permanently worried expression of his eyes. You cannot strike a child whom life costs such an effort. I told Silverman that I would surely denounce him if he continued in the apparatus which, I assured him, I meant to wreck. But we talked quietly. We wandered in the back streets beyond Florida Avenue. He confessed that he sometimes had his own doubts about the Communist Party. We parted gently." (13)

George Silverman remained a Soviet spy. He was employed in the Federal Coordinator of Transport, the United States Tariff Commission and the Labor Advisory Board of the National Recovery Administration. He became more important in 1942 when he was appointed as Chief of Analysis and Plans to the Assistant Chief of the Army Air Forces Air Staff for Material and Service and assigned to the Pentagon. In this post he managed to provide information to Jacob Golos and Elizabeth Bentley "on aircraft production, tank production, airplane deployment, and technological improvements to military hardware." (14)

House of Un-American Activities Committee

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included George Silverman, Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie, John Abt, Lee Pressman, Nathan Witt, Henry H. Collins and Donald Hiss. Silverman, Collins, Abt, Pressman and Witt all used the Fifth Amendment defence and refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC. (15)

Silverman was also named as a spy by Elizabeth Bentley. He was interviewed by the FBI but he still refused to answer questions. An agent reported that “he is in a position to furnish us considerable information if he could be persuaded to do so.” (16) He was unemployed for most of the rest of his life. According to his son, “after 1948 he wasn’t doing much of anything. He made some attempts to go into business with his brother-in-law, but nothing really worked out.”

Abraham George Silverman died of a heart-attack in New Jersey in January 1973.

Primary Sources

(1) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

The number of productive sources in the Soviet apparatus was small. But their activities were supported by a larger number of apparatus people-photographers, couriers, contact men and people who gave the use of their homes for secret photographic workshops. The sources did not know that most of these people existed and very few of the non-sources knew the identity of the sources. None of the active sources knew of one another's identity. I was the only man in the Washington apparatus who knew all of them and met them regularly or irregularly as the work required. Colonel Bykov knew the identity of all of them and had met all but two of the sources.

But the productive sources, though few in number, occupied unusually high (or strategic) positions in the Government. The No. i source in the State Department was Alger Hiss, who was then an assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State, Francis Sayre, the son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson. The No. 2 source in the same Department was Henry Julian Wadleigh, an expert in the Trade Agreements Division, to which he had managed to have himself transferred from the Agriculture Department. He had done so at the request of the Communist Party (Wadleigh was one of the fel¬low travelers) for the purpose of espionage. The source in the Treasury Department was the late Harry Dexter White. White was then an assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau. Later White became an assistant secretary of the Treasury, at which time he was known to Elizabeth Bentley. The source in the Aberdeen Proving Ground was Vincent Reno, an able mathematician who was living at the Proving Ground while he worked on a top-secret bombsight. Under the name Lance Clark, Reno had been a Communist organizer in Montana shortly before he went to work on the bombsight. The active source in the Bureau of Standards I shall call Abel Gross.

Thus, the group of active sources included: one assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State; one assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury; a mathematician working on one of the top-secret military projects of that time; an expert in the Trade Agreements Division of the State Department; an employe in the Bureau of Standards. The contacts included: two employes in the State Department and a second man in the Bureau of Standards.

In addition, the apparatus claimed the services of the Research Director of the Railroad Retirement Board, Mr. Abraham Georre Silverman, whose chief business, and a very exacting and unthankful one too, was to keep Harry Dexter White in a buoyant and co-operative frame of mind. Silverman also passed on as "economic adviser and chief of analysis and plans, assistant chief of air staff, material and services, air forces," into Miss Bentley's apparatuses. I did not recruit any of these men into the Communist Party or its work. With one possible exception (the mathematician), all of them had been engaged in underground Communist activity before I went to Washington or met any of them.

The espionage production of these men was so great that two (and, at one time, three) apparatus photographers operated in Washington and Baltimore to microfilm the confidential Government documents, summaries of documents or original memoranda, that they turned over. Two permanent photographic workshops were set up, one in Washington and one in Baltimore. Furthermore, the apparatus was constantly seeking to expand its opera¬tion. One of the Communists in the State Department and Vincent Reno, the man in the Aberdeen Proving Ground, were late recruits to the apparatus. Most of the sources were career men. In Government they could expect to go as far as their abilities would take them, and their abilities were considerable.

It is hard to believe that a more highly placed, devoted and dangerous espionage group existed anywhere. Yet they had rivals even in the Soviet service. While trying to expand the secret apparatus, Alger Hiss, quite by chance, ran across the trail of another Soviet espionage apparatus. This was the group headed (in Washington) by Hede Massing, the former wife of Gerhardt Eisler, the Communist International's representative to the Communist Party, U.S.A. In this second apparatus was Noel Field, a highly placed employe of the West European Division of the State Department. Field, his wife, brother and adopted daughter all disappeared into Russian-controlled Europe during the Hiss Case, in which he was involved. Among the Massing apparatus'' contacts was Noel Field's close friend, the late Laurence Duggan, who later became chief of the Latin-American Division of the State Department.

Moreover, the Washington apparatus to which I was assigned was only one wing of a larger apparatus. Another wing, also headed by Colonel Bykov, operated out of New York City, and was concerned chiefly with technical intelligence. It numbered among its active sources! the head of the experimental laboratory of a big steel company; a man strategically connected with a well-known arms company; and a former ballistics expert in the War Department. Presumably there were others. I learned the identities of these sources from an underground Communist known by the pseudonyms of "Keith" and "Pete." Keith had been Colonel Bykov's contact man with them. Later he became one of the photographers for the Washington apparatus. Incidentally, he has on all material points corroborated my testimony about him, about our joint activities, and the technical sources.

(2) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002)

For many years, Silverman had toiled away in obscure New Deal agencies like the Railroad Retirement Board, but in 1942 he won a transfer to the Pentagon. Soon afterward, he was able to arrange for Ullmann to join him there. Together they pilfered information on aircraft production, tank production, airplane deployment, and technological improvements to military hardware.

Silverman and Ullmann were probably Elizabeth's most significant sources because they stole military secrets-albeit, of course, on behalf of a wartime ally, not an enemy. But Elizabeth's bosses in Moscow still wanted insight into American policymaking. Fortunately for them, Greg Silvermaster happened to be friends with two powerful men: the chief economist in the White House and the chief economist in the Treasury Department.

(3) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997)

And there was the continual eruption of small crises Chambers, as "morale officer," was expected to solve. He had to handle difficult contacts, such as Abraham George Silverman, the economist at the Treasury Department, who, appropriately tightfisted, disliked paying Party dues. There was also Silverman's star contact, Treasury official Harry Dexter White, who alternated moods of abrasive hauteur with others of craven fear and was much happier handing over grandiose memorandums on monetary policy (he was a world-class authority in the field) than in furnishing the mundane reports of high-level Treasury discussions preferred by Bykov and his Moscow superiors.

(4) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

From my meeting with White, I went directly to the Railroad Retirement Board, where George Silverman was director of research, and walked unannounced into his office. He was much more surprised than White had been to see me, and, as I had expected, he was startled that I should come to his office. He hurried me down to the street and we walked along Florida Avenue, through the Negro section, where I could easily keep track of the white faces around me.

Silverman also knew nothing about my break. He was in no way suspicious of me. He told me that the espionage operation was still in full swing, only there were new faces. George was frankly happy to see me again and in the warm glow of his welcome, I felt my purpose go soft. Nothing could have hardened it so quickly as his news about the apparatus. He told me, further, that in a day or two, he was meeting his new contact man, a Russian with a pseudonym that Silverman mentioned (one of the innumerable Tom, Dick or Harrys), but which I have forgotten. He was meeting the Russian in a drug store near Thomas Circle. I said: "Tell him without fail that you have seen me and say that Bob sends his greetings."

A week or so later, I again walked unannounced into George Silverman's office at the Railroad Retirement Board. This time he looked terrified. Again he hurried me downstairs. "What has happened?" he asked in a frightened voice. "What has happened? When I gave (Tom, Dick or Harry) your message, he jumped up from the table and grabbed his hat. He said: 'Don't ever try to contact me again unless you hear from me first.' Then he rushed out of the drug store."

Then I told George. I told him just as grimly as I had told Harry White. (Since, on my second visit, Silverman still knew nothing about my visit to White, I can only assume that under the new management of the apparatus, White and Silverman, who had formerly worked together, had been separated like the other workers. )Like White, Silverman was a slight, nervous little man. But he lacked a pushing quality that I disliked in White. He aroused a protective feeling. For, in fact, he was a child, and the effort that it cost him to be a man was apparent in the permanently worried expression of his eyes. You cannot strike a child whom life costs such an effort. I told Silverman that I would surely denounce him if he continued in the apparatus which, I assured him, I meant to wreck. But we talked quietly. We wandered in the back streets beyond Florida Avenue. He confessed that he sometimes had his own doubts about the Communist Party. We parted gently.

And yet, when Elizabeth Bentley took over the Soviet espionage apparatuses in Washington, she found George Silverman still busily at work. He had gone ahead in the American Government service. He had become economic adviser and chief of analysis and plans to the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (the unhappy General Bennett Meyers ), in the Materiel and Services Division of the Air Force. Silverman had advanced in the Soviet service too. He no longer had to play underground nursemaid to Harry Dexter White. He had, according to Miss Bentley, become a full-fledged productive source himself.

My last call on George Silverman ended my private offensive against the underground in Washington. One part of that offensive I did not go through with. There was a photographic workshop in Washington to which I had a key. Part of my plan had been to go there and wreck the equipment. This was the most dangerous venture possible. The workshop was one place where the G.P.U. could easily prepare a trap for me and even "commit a good natural death." I found that I lacked the courage for this attempt.

(5) Athan Theoharis, Chasing Spies (2002)

Like other subpoenaed witnesses before the grand jury, White did not know what government prosecutors knew about his alleged activities and those of his colleagues in the Treasury Department He could refuse to cooperate, denying any part in espionage. But a denial could render him vulnerable to a perjury indictment should another of the subpoenaed witnesses break and testify, to his own and the other suspects' actions. To avoid this risk, White sought to concert his testimony with at least two other Treasury Department employees subpoenaed by the grand jury, Frank Coe and George Silverman. In so doing, White became vulnerable to indictment for obstruction of justice.

Subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury, White was first asked about his relationship with a number of the individuals whom Bentley had named as members of the Silvermaster-Perlo espionage rings. Then he was asked whether he had played a role in the hiring of specifically named individuals, and whether any of them were Communists or had solicited classified information. White acknowledged having a professional and in some cases personal association with some of these named individuals, but he explicitly denied any knowledge of their politics or their possible involvement in espionage, though he expressed his doubts about either matter. Until then a confident witness, White was blindsided when U.S. attorney Thomas Donegan asked whether, before his grand jury appearance he, Frank Coe, and George Silverman had discussed how each would respond to grand jury questions about their earlier relationship and activities. White admitted to an accidental meeting with Coe at which he had inquired in passing about Coe's subpoenaed appearance. Donegan followed up by asking whether White had telephoned Silverman and had arranged a second meeting among the three of them. Changing his testimony to admit to this second meeting, White described it as a social discussion over a beer, not a purposeful effort to frustrate the work of the grand jury. Without explicitly admitting that his knowledge of White's actions came from an FBI wiretap, Donegan had subtly conveyed his awareness of this telephone conversation. An unprepared White did not realize that this information had been illegally obtained and thus could not be used to indict him. In any event, White denied that he had obstructed the work of the grand jury. Donegan could not press the matter, for to have done so would have required him to reveal that his question had been based on an illegal wiretap.

References

(1) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952) page 31

(2) Susan Jacoby, Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009) pages 79-80

(3) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 48

(4) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) page 108

(5) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 43

(6) House of Un-American Activities Committee (6th December, 1948)

(7) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) page 108

(8) Julian Wadleigh, Why I Spied for the Communists, New York Post (14th July, 1949)

(9) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) page 111

(10) Benjamin Gitlow, The Whole of Their Lives: Communism in America (1948) pages 333-334

(11) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952) page 439

(12) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952) page 68

(13) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952) page 69

(14) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 48

(15) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) page 246

(16) A.S. Brent to C.E. Hennrich (30th October, 1950)