Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss, the son of a businessman, Charles Hiss, was born in Baltimore on 11th November, 1904. He had two sisters and two brothers: Anna (1893), Mary Anne (1895), Bosley (1900) and Donald (1906).

When he was only two years old, his father committed suicide by cutting his throat with a razor. Alger Hiss later wrote in Recollections of a Life (1988): "My father had been an executive of a large wholesale dry-goods firm, a man overwhelmed by financial and family worries. Suicide was a blow that was shameful as well as tragic for any family in those years, and mine reacted to the shame by silence. I did not know that my father had taken his own life until I was about ten years old and I overheard the remark of a neighbor sitting on her front steps talking with another neighbor." Hiss claimed that he had a happy childhood: "On the whole, however, my childhood memories are of a lively and cheerful household, full of the bustle of constant comings and goings. The shock of learning by accident of my father's suicide was lessened by the warm family spirit I remember so well."

After the death of Charles Hiss, Eliza Millemon Hiss (Aunt Lila), his father's unmarried middle sister, moved into the family home: "I was closer to her (Aunt Lila) than I was to my mother. This may have been partly due to my mother's being the family magistrate, although her severest punishment was a slap with a ruler on the palm of an extended hand. When I went to my mother for solace of a hurt, I was likely to receive a homily on how best to get on in the world. In contrast, Aunt Lila could be counted on for sympathetic understanding.... Aunt Lila wanted something different for us, something less worldly. She wanted us to share her love of literature, her respect for learning and morality."

Childhood of Alger Hiss

The journalist, Murray Kempton, also lived in Baltimore at this time: "They lived near Lanville Street, which is the heart of shabby gentility in Baltimore. As he grew up, more substantial families around him were moving out into the suburbs. The Hisses stayed there in a neighborhood slowly running down. They were not a family of special social prestige, but the Baltimore in which Alger Hiss grew up had its own corner for the sort of family that... rested on that border between respectability and assured position. In the circumstances of her life, society felt a particular sympathy for Alger Hiss's mother."

In 1926 Alger Hiss suffered another family tragedy when his older brother, Bosley Hiss, died of Bright's disease: "I have long thought that Bosley was romantically elevated... within the family. His charm and precocious talents were enhanced and frozen by his lingering illness and early death... After his death, I heard for a number of years constant references... about his magnetism, wit, and scintillating bon mots deflating pompous and self-important people... He had a somewhat willful, romantic vanity that showed itself in scorn for complacency and hypocricy."

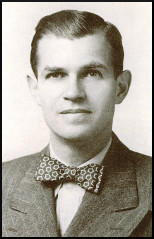

Hiss did very well at secondary school. His high school yearbook described him as "a witty, happy, optimistic person," whose "happy habits" made him "irresistible" to his contemporaries. One of his cousins said he had "an unusual genial and happy nature," and another relative commented that he "inherited... unselfishness, tolerance, and a broad outlook" from his father. It seems that he "hardly ever to have expressed... any hostility" towards "his surroundings or acquaintances".

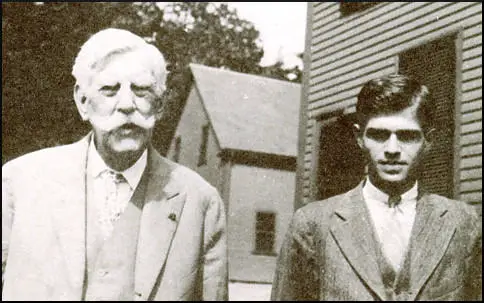

Felix Frankfurter

Hiss was educated at John Hopkins University and Harvard Law School (1926-29), where he came under the influence of Felix Frankfurter. In his autobiography he pointed out: "Felix Frankfurter was far and away the most colorful and controversial member of the faculty.... He was always conspicuous, despite his small stature, as he moved about the campus. This was because as he bounced along - short, dynamic, articulate - he was invariably surrounded by a cluster of students. Frankfurter was always teaching, in class and out. His didactic style was challenging, even confrontational. He invited discussion and he reveled in sharp exchanges. These continued after class had ended. But Frankfurter was not popular with the majority of his students or his fellow faculty members. In both cases the reasons, I believe, were the same. Frankfurter was cocky, abrasive, and outspoken. His style was simply not theirs. In addition, Frankfurter was the leader of the liberal wing of the faculty. Most of his older colleagues were politically conservative, as were most of the students."

Frankfurter was also impressed with Hiss and arranged for him to work for the Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes. "Near the conclusion of my final year at Harvard Law School, I was surprised - indeed, overwhelmed - to receive a handwritten note from Justice Holmes. It informed me that on the recommendation of Felix Frankfurter, my favorite Harvard professor, the Justice had chosen me as his private secretary for the following year. Holmes wrote that if I were to accept I was to report to his house in Washington on the Friday before the first Monday in October (the fall term of the Supreme Court begins on that Monday). He added that because of his age - he was then eighty-eight - he must reserve the right to resign or die. This appointment was to me a much more important certification of my accomplishment as a law student than was the diploma iself. The opportunity to continue my legal education under the supervision of this eminent jurist was by far the greatest prize the law school could offer."

In 1929, Hiss's sister, Mary Ann, after a late-night argument with her husband, Elliot Emerson, a Boston stockbroker, had killed herself by swallowing a bottle of Lysol. Apparently they had been having financial problems and like her father, Emerson was facing bankrupcy. When he heard the news he described himself as "shocked and uncomprehending" and described it as a "sudden, irrational act."

Marriage

Alger Hiss met Priscilla Fansler when he was only 19 on a trip to London. Although they exchanged addresses, she showed no particular interest in him. In 1926 she married Thayer Hobson. Later that year she gave birth to a son, Timothy. However, shortly afterwards they separated, and eventually, in January 1929, divorced. She then began a relationship with William Brown Meloney, who worked with her on Time Magazine, and was a married man. Priscilla became pregnant and hoped to marry Meloney. He rejected the idea and demanded that she had an abortion.

Meloney broke of his relationship with Priscilla. Soon afterwards she resumed her relationship with Alger Hiss. As G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004), has pointed out: "From her perspective, Alger Hiss may have seemed a more attractive prospect for marriage. He was holding down a very prestigious job, with a decent salary, and he was likely to have a bright future in the legal profession. His continuing to court her, after she had twice rebuffed him for other men, suggested that his attitude to her approached devotion. He had already shown himself to be gifted at helping people in distress. He was a prospective father for her son Timothy." Alger's mother apparently objected to the relationship and sent him a telegram on the day of the wedding, on 11th December, 1919, that warned, "Do Not Take This Fatal Step."

Susan Jacoby has argued in Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009) that the marriage was out of character: "The only unusual step Hiss took as a young man on the way up was his marriage to Priscilla Fansler Hobson, who had a young son by her first husband. Marrying a divorced woman in 1929 was not a move calculated to advance one's social or career prospects... The young attorney was also violating Justice Holmes's well-known rule that his secretaries remain unmarried in order to devote their full attention to him."

The Great Depression

After leaving the employment of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Hiss joined Choate, Hall & Stewart, a Boston law firm. "I took an apartment in Cambridge and went by subway to their offices on State Street... The advent of the Depression had already made a differeence in the mood and general atmosphere of Boston. Along with others who had been concerned only occasionally, and in a minor way, with social conditions, I became increasingly aware of the growing unemployment and economic malaise. One's responsibility for the worsened conditions of others became a recurring topic."

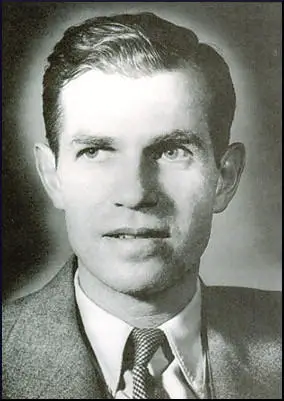

In 1931 Alger Hiss moved to New York City and joined the firm of Cotton, Franklin, Wright, and Gordon. His biographer, Denise Noe, pointed out: "As a young man, the slim, handsome, and dapper Alger impressed most people as self-confident and more than a few as arrogant. He appeared to have avoided the depression that afflicted other members of his family and achieved success at a young age."

Priscilla Hiss held left-wing opinions and in 1930 joined the Socialist Party of America. Her initial involvement consisted primarily of working at soup kitchens set up for unemployed people who lived in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. She told her husband about "the growing breadlines and soup kitchens, the shanty towns in parks and vacant lots, the beggars that gave sharp reality to accounts of similar and even worse conditions throughout the country." Hiss later claimed: "I had concluded that the Depression was not a natural disaster; it had been avoidable. It was the result of decrepit social structures, of mismanagement and greed. The old order had for long years blocked needed reforms and by its blunders and corruption had precipitated the crash. Our nation, rich in resources and talent, would under vigorous new leadership undo the damage and enact reforms that would prevent future disasters."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

Alger Hiss had regular meetings with Felix Frankfurter and the two men discussed the political situation in the United States: "From his teaching and my own observations I had become convinced that only large-scale governmental activities could meet the demands of the Depression. I had begun to see the total inadequacy of private charitable activities, and I became acutely aware of the shallowness of my conventional concern for the welfare of others. Later, when I moved to New York City, I saw daily the growing breadlines and soup kitchens, the shanty towns in parks and vacant lots, the beggars along with men who masked their appeal for alms by 'selling' an apple. My continuous personal encounter with mounting misery gave sharp reality to accounts of similar and even worse conditions throughout the country."

In the 1932 Presidential Election Hiss supported Franklin D. Roosevelt. "Once Roosevelt's candidacy was announced, I was strongly attracted to his banner, but had no thought that I would do more to advance his cause than urge my friends to vote for him. Nonetheless, I had wanted to do something constructive in a private capacity, something that would help in a small way to set things right. That desire to participate led me to offer my legal skills to a small group of young and similarly motivated New York lawyers who had come together to issue a journal for labor lawyers and those representing hard-pressed farmers."

Alger Hiss and the New Deal

President Roosevelt appointed Henry A. Wallace as Secretary of Agriculture. On 11th March, Wallace reported: "The farm leaders were unanimous in their opinion that the agricultural emergency calls for prompt and drastic action.... The farm groups agree that farm production must be adjusted to consumption, and favor the principles of the so-called domestic allotment plan as a means of reducing production and restoring buying power." The conference also called for emergency legislation granting Wallace extraordinarily broad authority to act, including power to control production, buy up surplus commodities, regulate marketing and production, and levy excise taxes to pay for it all.

John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, the authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have pointed out: "The sense of urgency was hardly theoretical. A true crisis was at hand. Across the Corn Belt, rebellion was being expressed in ever more violent terms. In the first two months of 1933, there were at least seventy-six instances in fifteen states of so-called penny auctions, in which mobs of farmers gathered at foreclosure sales and intimidated legitimate bidders into silence. One penny auction in Nebraska drew an astounding crowd of two thousand farmers. In Wisconsin farmers bent on stopping a farm sale were confronted by deputies armed with tear gas and machine guns. A lawyer representing the New York Life Insurance Company was dragged from the courthouse in Le Mars, Iowa, and the sheriff who tried to help him was roughed up by a mob."

A new agency, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) was created to oversee programs designed to alleviate the economic plight of farmers. Felix Frankfurter arranged for Hiss to be offered a position working under Jerome Frank AAA's general counsel. This brought him into conflict with the head of the AAA, George N. Peek. It has been argued by John C. Culver that "Frank was liberal, brash, and Jewish. Peek loathed everything about him. In addition, Frank surrounded himself with idealistic left-wing lawyers... whom Peek also despised." This included Hiss, Adlai Stevenson, and Lee Pressman. Peek later wrote that the "place was crawling with... fanatic-like... socialists and internationalists."

The Ware Group

Harold Ware, the son of Ella Reeve Bloor, was a member of the American Communist Party and a consultant to the AAA. Ware established a "discussion group" that included Alger Hiss, Nathaniel Weyl, Laurence Duggan, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Henry H. Collins, Lee Pressman and Victor Perlo. Ware was working very close with Joszef Peter, the "head of the underground section of the American Communist Party." It was claimed that Peter's design for the group of government agencies, to "influence policy at several levels" as their careers progressed".

Susan Jacoby, the author of Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009), has pointed out: "Hiss's Washington journey from the AAA, one of the most innovative agencies established at the outset of the New Deal, to the State Department, a bastion of traditionalism in spite of its New Deal component, could have been nothing more than the rising trajectory of a committed careerist. But it was also a trajectory well suited to the aims of Soviet espionage agents in the United States, who hoped to penetrate the more traditional government agencies, like the State, War, and Treasury Departments, with young New Dealers sympathetic to the Soviet Union (whether or not they were actually members of the Party). Chambers, among others, would testify that the eventual penetration of the government was the ultimate aim of a group initially overseen in Washington by Hal Ware, a Communist and the son of Mother Bloor... When members did succeed in moving up the government ladder, they were supposed to separate from the Ware organization, which was well known for its Marxist participants. Chambers was dispatched from New York by underground Party superiors to supervise and coordinate the transmission of information and to ride herd on underground Communists - Hiss among them - with government jobs."

Whittaker Chambers was a key figure in the Ware Group: "The Washington apparatus to which I was attached led its own secret existence. But through me, and through others, it maintained direct and helpful connections with two underground apparatuses of the American Communist Party in Washington. One of these was the so-called Ware group, which takes its name from Harold Ware, the American Communist who was active in organizing it. In addition to the four members of this group (including himself) whom Lee Pressman has named under oath, there must have been some sixty or seventy others, though Pressman did not necessarily know them all; neither did I. All were dues-paying members of the Communist Party. Nearly all were employed in the United States Government, some in rather high positions, notably in the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Justice, the Department of the Interior, the National Labor Relations Board, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Railroad Retirement Board, the National Research Project - and others."

The Munitions Investigation Committee

In 1934 Alger Hiss was appointed as chief counsel to the Munitions Investigating Committee that had been established by Gerald P. Nye. Hiss explained in Recollections of a Life (1988): "In the late summer of 1934, I took an additional job - that of counsel to the Senate Committee to Investigate the Munitions Industry. That committee, headed by Senator Gerald P. Nye, Republican of North Dakota, had asked the Agricultural Adjustment Administration for the loan of my services. The committee received strong support from two large sectors of the public. One group, which included almost all veterans, resented the profiteering associated with arms contracts. The other, especially strong in the Midwest, cherished the long-standing American isolationist sentiments."

Hiss admitted that: "Much of the New Deal's ardor was prompted by resentment of the corporate greed that had preceded and in part precipitated the Depression. Consequently, many of us New Dealers were sympathetic to the Nye Committee's populist fulminations against war profiteers.... The initial concentration on the questionable practices and the profits of aviation and shipbuilding concerns was followed by investigations of the Du Pont company and its relations with its foreign counterparts and other American businesses. The resulting hearings demonstrated cartel-like arrangements among firms like Vickers of Britain, Bofors of Sweden, Schneider-Creusot of France, and I. G. Farben of Germany."

Hiss involvement with the Munitions Investigating Committee made him especially interesting to Joszef Peter. In the course of its investigations of the munitions industry, Hiss would have access to correspondence that discussed military policies of the United States government. Peter asked Whittaker Chambers to come to Washington to oversee the formation of a special "parallel apparatus" whose members would report directly to the GPU, the Soviet agency in charge of military intelligence.

The State Department

In 1936, Alger Hiss began working under Cordell Hull in the State Department. Alger was an assistant to Assistant Secretary of State Francis Bowes Sayre and then special assistant to the director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs. When Sayre went to the Philippines in late 1939 as United States High Commissioner. Hiss now became an assistant to Stanley Hornbeck, a special adviser to Hull on Far Eastern affairs.

Alger Hiss argues that like most of his colleagues he was shocked by the attack on Pearl Harbor: "Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor caught the State Department as completely by surprise as it did the naval and military personnel at the base itself. I arrived at the Department that Sunday afternoon to a scene of confusion and uncertainty. Like me, others had hurried from their homes on hearing the radio announcement. Knots of officials congregated in the corridors and discussed the astounding news. Succeeding reports from Hawaii were dismaying. The damage had been catastrophic. The Pacific fleet had been put out of action."

In 1944 he became an assistant to Leo Pasvolsky, the first head of the Office of Special Political Affairs. In this capacity he worked closely with Secretary of State Edward Stettinius in planning for the post-war world. "By 1943, the scales of war had tilted more and more in our favor. The State Department increased its emphasis on preparing terms for peace and formulating our postwar policies. I was transferred to the division engaged in postwar planning, including especially plans for the United Nations. I served as secretary of the Dumbarton Oaks Conversations in the summer of 1944."

Yalta Conference

In February, 1945, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt met to discuss what would happen after the Second World War. The conference was held in Yalta on the north coast of the Black Sea in the Crimean peninsula. With Soviet troops in most of Eastern Europe, Stalin was in a strong negotiating position. Roosevelt and Churchill tried hard to restrict post-war influence in this area but the only concession they could obtain was a promise that free elections would be held in these countries. Alger Hiss attended the conference with his boss, Edward Stettinius.

Some of the British politicians who attended the Yalta Conference believed that Stalin achieved the most from the negotiations. For example, Anthony Eden, the British foreign minister, pointed out: "Roosevelt was, above all else, a consummate politician. Few men could see more clearly their immediate objective, or show greater artistry in obtaining it. As a price of these gifts, his long-range vision was not quite so sure. The President shared a widespread American suspicion of the British Empire as it had once been and, despite his knowledge of world affairs, he was always anxious to make it plain to Stalin that the United States was not 'ganging up' with Britain against Russia. The outcome of this was some confusion in Anglo-American relations which profited the Soviets. Roosevelt did not confine his dislike of colonialism to the British Empire alone, for it was a principle with him, not the less cherished for its possible advantages. He hoped that former colonial territories, once free of their masters, would become politically and economically dependent upon the United States, and had no fear that other powers might fill that role."

However, Alger Hiss disagreed with this analysis: "As I look back on the Yalta Conference after more than forty years, what stand out strikingly are the surprising geniality as host and the conciliatory attitude as negotiator of Joseph Stalin, a man we know to have been a vicious dictator. I am also reminded that in almost all of the analyses and criticism of the Yalta accords that I have read, I have not seen adequate recognition of the fact that it was we, the Americans, who sought commitments on the part of the Russians. Except for the Russian demand for reparations, coolly received by the United States, all the requests were ours. And, except for Poland, our requests were finally granted on our own terms. In agreeing to enter the war against Japan, Stalin asked for and was granted concessions of his own, but the initiative had been ours - we had urgently asked him to come to our aid."

Christopher Andrew, the author of The Mitrokhin Archive (1999), is an historian who believes that Joseph Stalin completely out-negotiated Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill: "The problem which occupied most time at Yalta was the future of Poland. Having already conceded Soviet dominance of Poland at Tehran, Roosevelt and Churchill made a belated attempt to secure the restoration of Polish parliamentary democracy and a guarantee of free elections. Both were outnegotiated by Stalin, assisted once again by a detailed knowledge of the cards in their hands. He knew, for example, what importance his allies attached to allowing some 'democratic' politicians into the puppet Polish provisional government already established by the Russians. On this point, after initial resistance, Stalin graciously conceded, knowing that the 'democrats' could subsequently he excluded. After first playing for time, Stalin gave way on other secondary issues, having underlined their importance, in order to preserve his allies' consent to the reality of a Soviet-dominated Poland. Watching Stalin in action at Yalta, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office, Sir Alexander Cadogan, thought him in a different league as a negotiator to Churchill and Roosevelt."

It has been argued by G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004) that Hiss himself had a profound impact on the conference. "Hiss's increased access to confidential sources, especially after he became an assistant to Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, made it possible for him to funnel intelligence information of considerable value to the Soviets. For example, Hiss's placement, coupled with that of the British Soviet agent Donald Maclean, who held a high-level post in the British Embassy in Washington from 1944 to 1949, meant that Stalin had a firm grasp of the postwar goals of the United States and Great Britain before the Yalta Conference."

White points out that Hiss, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby and other British-based Soviet agents in "providing a regular flow of classified intelligence or (confidential) documents in the run-up to (Yalta.)" A recently released KGB document dated March 1945 shows that the Soviets were very pleased with Hiss's contribution during the Yalta Conference: "Recently ALES (Hiss) and his whole group were awarded Soviet decorations. After the Yalta conference, when he had gone on to Moscow, a Soviet personage in a cry responsible position (ALES gave to understand that it was Comrade Vyshinsky, deputy foreign minister), allegedly got in touch with ALES and at the behest of the military NEIGHBOURS (GRU) passed oil to him their gratitude and so on."

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers stopped being a Soviet spy in 1938. The following year he left the American Communist Party and joined Time Magazine. It soon became clear that Chambers was a strong anti-communist and this reflected the views of the owner of the magazine, Henry Luce, who arranged for him to be promoted to senior editor. Later that year he joined the group that determined editorial policy. Chambers wrote in his memoirs: "My debt and my gratitude to Time cannot be measured. At a critical moment, Time gave me back my life."

In 1939, Chambers met the journalist, Isaac Don Levine. Chambers told Levine that there was a communist cell in the United States government. Chambers recalled in his book, Witness (1952): "For years, he (Levine) has carried on against Communism a kind of private war which is also a public service. He is a skillful professional journalist and a notable ghost writer... From the first, Levine had urged me to take my story to the proper authorities. I had said no. I was extremely wary of Levine. I knew little or nothing about him, and the ex-Communist Party, but the natural prey of anyone who can turn his plight to his own purpose or profit."

In August 1939, Levine arranged for Chambers to meet Adolf Berle, one of the top aides to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He later wrote in Witness: "The Berles were having cocktails. It was my first glimpse of that somewhat beetle-like man with the mild, intelligent eyes (at Harvard his phenomenal memory had made him a child prodigy). He asked the inevitable question: If I were responsible for the funny words in Time. I said no. Then he asked, with a touch of crossness, if I were responsible for Time's rough handling of him. I was not aware that Time had handled him roughly. At supper, Mrs. Berle took swift stock of the two strange guests who had thus appeared so oddly at her board, and graciously bounced the conversational ball. She found that we shared a common interest in gardening. I learned that the Berles imported their flower seeds from England and that Mrs. Berle had even been able to grow the wild cardinal flower from seed. I glanced at my hosts and at Levine, thinking of the one cardinal flower that grew in the running brook in my boyhood. But I was also thinking that it would take more than modulated voices, graciousness and candle-light to save a world that prized those things."

After dinner Chambers told Berle about Alger Hiss being a spy for the Soviet Union. He also told him that Joszef Peter was "responsible for Washington Sector". He also identified the State and Treasury Departments as containing several underground members of the American Communist Party. This included Donald Hiss, Harold Ware, Nathan Witt and Julian Wadleigh. Chambers left the meeting with the impression that Berle was going to pass this information to Roosevelt. Although he did record his conversation with Chambers in a memorandum that suggested a prompt follow-up, nothing happened for several years.

According to Chambers, Berle reacted to the news about Hiss with the comment: "We may be in this war within forty-eight hours and we cannot go into it without clean services." John V. Fleming, has argued in The Anti-Communist Manifestos: Four Books that Shaped the Cold War (2009) Chambers had "confessed to Berle the existence of a Communist cell - he did not yet identify it as an espionage team - in Washington." Berle, who was in effect the president's Director of Homeland Security, raised the issue with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, "who profanely dismissed it as nonsense."

In 1943 the FBI received a copy of Berle's memorandum. Whittaker Chambers was interviewed by the FBI but J. Edgar Hoover concluded, after being briefed on the interview, that Chambers had little specific information. However, this information was sent to the State Department security officials. One of them, Raymond Murphy, interviewed Chambers in March 1945 about these claims. Chambers now gave full details of Hiss's spying activities. A report was sent to the FBI and in May, 1945, they had another meeting with Chambers.

In August 1945, Elizabeth Bentley walked into an FBI office and announced that she was a former Soviet agent. In a statement she gave the names of several Soviet agents working for the government. This included Harry Dexter White and Lauchlin Currie. Bentley also said that a man named "Hiss" in the State Department was working for Soviet military intelligence. In the margins of Bentley's comments about Hiss, someone at the FBI made a handwritten notation: "Alger Hiss".

The following month, Igor Guzenko, a clerk in the Soviet Embassy in Ottowa, defected to the Canadian authorities. He gave them a large number of documents detailing the existence of a large Soviet military intelligence network in Canada. Guzenko was also interviewed by the FBI. He told them that "the Soviets had an agent in the United States in May 1945 who was an assistant to the secretary of state, Edward R. Stettinius." Alger Hiss was Stettinius's assistant at the time."

The FBI sent a report on Hiss to the Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in November 1946. It concluded that Hiss was probably a Soviet agent. Hiss was interviewed by D.M. Ladd, the FBI's Assistant Director, and denied any associations with Communism. The State Department security officials restricted his access to confidential documents, and the FBI wiretapped his office and home phones.

Dean Acheson came under pressure to sack Hiss. Acheson refused to do this and instead contacted John Foster Dulles, who was on the board of directors of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Dulles arranged for Hiss to become president of the organization. At first Hiss refused to go and said he would rather stay and answer his critics. However, Acheson insisted and suggested that "this is the kind of thing which rarely, if ever, gets cleared up."

House of Un-American Activities Committee

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included Alger Hiss.

Chamber's accusations made headline news. Hiss immediately sent a telegram to John Parnell Thomas, HUAC's acting chairman: "I do not know Mr. Chambers, and, so far as I am aware, have never laid eyes on him. There is no basis for the statements about me made to your committee." Hiss asked for the opportunity to "appear... before your committee to make these statements formally and under oath." He also sent a copy of the telegram to John Foster Dulles.

On 5th August, 1948, Hiss appeared before the HUAC: "I am not and never have been a member of the Communist Party. I do not and never have adhered to the tenets of the Communist Party. I am not and never have been a member of any Communist-front organization. I have never followed the Communist Party line, directly or indirectly. To the best of my knowledge, none of my friends is a Communist.... To the best of my knowledge, I never heard of Whittaker Chambers until 1947, when two representatives of the Federal Bureau of investigation asked me if I knew him... I said I did not know Chambers. So far as I know, I have never laid eyes on him, and I should like to have the opportunity to do so."

G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004) has pointed out: "By his categorical disassociation of himself from even the slightest connection with Communism or Communist-front activities, Hiss set in motion a narrative of his career that he would devote the rest of his life to telling and retelling. In that narrative Hiss was simply a young lawyer who had gone to Washington and became committed to the policies of the New Deal and international peace. His career had been a consistent effort to promote those ideals. He had never been a Communist, and those who were accusing him of being such were seeking to scapegoat him for partisan purposes. They were a pack of liars, and he was their intended victim."

Richard Nixon now joined in the controversy. He argued that "while it would be virtually impossible to prove that Hiss was or was not a Communist... the HUAC... should be able to establish by corroborative testimony whether or not the two men knew each other." Nixon now became the head of a subcommittee to pursue the inquiry of Alger Hiss. HUAC called Hiss back for an executive session in New York City. This time he admitted that he did know Whittaker Chambers but at the time he used the name George Crosley. He also agreed with Chambers's testimony that he had rented him an apartment but denied that he was ever a member of the American Communist Party. Hiss added: "May I say for the record at this point that I would like to invite Mr. Whittaker Chambers to make those same statements out of the presence of the committee, without their being privileged for suit for libel. I challenge you to do it, and I hope you will do it damned quickly."

On 17th August, 1948, Chambers repeated his claim that "Alger Hiss was a communist and may be now." He added, "I do not think Mr. Hiss will sue me for slander or libel." At first Hiss hesitated but he realised that if he did not sue Chambers he would be considered guilty of being a communist. After lengthy discussions with several lawyers, Hiss filed a suit against Chambers on 27th September, 1948.

Alger Hiss Perjury Trial

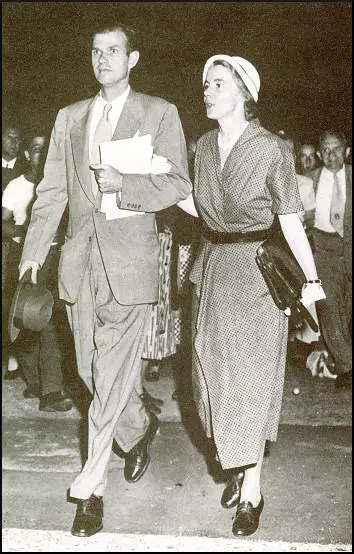

On 15th December, 1948, the grand jury asked Alger Hiss whether he had known Whittaker Chambers after 1936, and whether he had passed copies of any stolen government documents to Chambers. As he had done previously, Hiss answered no to both questions. The grand jury then indicted him on two counts of perjury. The New York Times reported that he "appeared solemn, anxious, and unhappy" with a grim and worried look". It added that to "observers it seemed obvious that he had not expected to be indicted".

The trial began in May 1949. Hiss later recalled in Recollections of a Life (1988): "Running the gauntlet of the press was, in a sense, a more wearing ordeal than the trials themselves. Inside the courtroom, I not only had the support of my lawyers, but about half of those who daily filled the courtroom were friends or evident sympathizers. But almost every morning as my wife and I left the door of our apartment house at Eighth Street and University Place, unaccompanied by supporters, we were besieged by reporters and often photographers. New York then had several more newspapers than it does now and all the papers and the wire services covered the trials. Dutiful lawyer to the core, I answered no questions, pointing out as politely as possible that it would be inappropriate for me to comment while the case was still in progress. Likewise, I also would not stop to pose for photographers, although they were of course free to take shots as we walked along. In consequence, we were often a public spectacle, Priscilla and I walking resolutely along with photographers walking backward a few paces ahead of us."

The trial began in May 1949. The first piece of evidence concerned a car purchased by Chambers for $486.75 from a Randallstown car dealer on 23rd November, 1937. Chambers claimed that Hiss had given him $400 to buy the car. The prosecution was able to show that on 19th November Hiss had withdrawn $400 from his bank account. Hiss claimed that this was to buy furniture for a new house. But the Hisses had not signed a lease on any house at that time, and could produce no receipts for the furniture.

The main evidence that the prosecution produced consisted of sixty-five pages of re-typed State Department documents, plus four notes in Hiss's handwriting summarizing the contents of State Department cables. Chambers claimed Alger Hiss had given them to him in 1938 and that Priscilla Hiss had retyped them on the Hisses' Woodstock typewriter. Hiss initially denied writing the note, but experts confirmed it was his handwriting. The FBI was also able to show that the documents had been typed on Hiss's typewriter.

In the first trial Thomas Murphy stated that if the jury did not believe Chambers, the government had no case, and, at the end, four jurors remained unconvinced that Chambers had been telling the truth about how he had obtained the typed copies of documents. They thought that somehow Chambers had gained access to Hiss's typewriter and copied the documents. The first trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict.

The second trial began in November 1949. One of the main witnesses against Hiss in the second trial was Hede Massing. She claimed that at a dinner party in 1935 Hiss told her that he was attempting to recruit Noel Field, then an employee of the State Department, to his spy network. Whittaker Chambers claims in Witness (1952) that this was vital information against Hiss: "At the second Hiss trial, Hede Massing testified how Noel Field arranged a supper at his house, where Alger Hiss and she could meet and discuss which of them was to enlist him. Noel Field went to Hede Massing. But the Hisses continued to see Noel Field socially until he left the State Department to accept a position with the League of Nations at Geneva, Switzerland-a post that served him as a 'cover' for his underground work until he found an even better one as dispenser of Unitarian relief abroad."

Alger Hiss wrote in his autobiography, Recollections of a Life (1988): "Throughout the first trial and most of the second, I was confident of acquittal. But as the second trial wore on, I realized that it was no ordinary one. The entire jury of public opinion, all of those from whom my juries had been selected, had been tampered with. Richard Nixon, my unofficial prosecutor, seeking to build his career on getting a conviction in my case, had from the days of the congressional committee hearings constantly issued public statements and leaks to the press against me. There were moments when I was swept with gusts of anger at the prosecutor's bullying tactics with my witnesses and his devious insinuations in place of evidence - tactics that unfortunately are all too common in a prosecutor's bag of tricks... It was almost unbearable to hear the sneers of the prosecutor as he cross-examined my wife and other witnesses."

Hiss was unhappy with the way he was dealt with in court: "When it was my turn to be cross-examined, the ordeal was of a different sort. Here, court procedures are all weighted in favor of the questioner. The witness may not argue or explain. I was able only to answer directly and briefly, however weighted or hostile the question. My lawyer could object to improper questions, but at the risk of letting the jury get the impression that we were reluctant to have the subject explored. But I was at least not forced to remain mutely impassive, and I was confident that later my lawyer could correct false impressions which bullying cross-examination might leave. It was especially in those moments of provocation triggered by false insinuations that anger and fatigue were to be guarded against. I lost my temper at least once and immediately realized I had erred. The etiquette of the bull ring did not permit the tormented to show even annoyance. I sensed that the jury thought the prosecutor must have scored a point if I reacted so sharply."

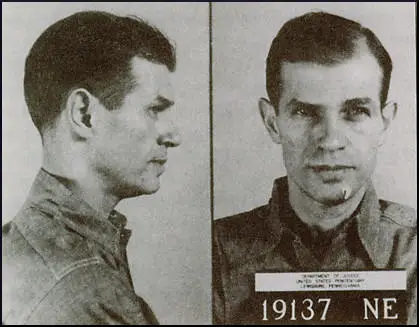

Lewisburg Penitentiary

The second jury found Hiss guilty of two counts of perjury and on 25th January, 1950, he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment. The Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was asked later that day about the Hiss trial. He replied: "Mr. Hiss's case is before the courts, and I think it would be highly improper for me to discuss the legal aspects of the case, or the evidence, or anything to do with the case. I take it the purpose of your question was to bring something other than that out of me... I should like to make it clear to you that whatever the outcome of any appeal which Mr. Hiss or his lawyers may take in this case, I do not intend to turn my back on Alger Hiss. I think every person who has known Alger Hiss, or has served with him at any time, has upon his conscience the very serious task of deciding what his attitude is, and what his conduct should be. That must be done by each person, in the light of his own standards and his own principles... My friendship is not easily given, and not easily withdrawn."

Alger Hiss's appeal was unanimously denied and on 22nd March, 1951, he was sent to a maximum security federal facility in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. "Often while I was at Lewisburg, and since, I have remarked upon the similarities between prison and the army. Both institutions are designed to control large numbers of men. Both supply food, clothing, and shelter for large groups. Both must organize the activities of their charges and provide some recreation to balance the workload. Most important of all, both must impose strict discipline in order to ensure that these functions are carried out. An essential element in the successful implementation of discipline by each institution is the process of depersonalization. Privacy disappears; there is no individuality of dress; food and activities are as uniform as the clothing. At Lewisburg we marched in columns of twos to meals and to movies."

Alger Hiss gave free legal advice to Frank Costello and other Mafia figures. This gave him protection from anti-Communist inmates. On 27th November, 1954, William Remington was murdered by two inmates, George McCoy and Lewis Cagle. Remington, like Hiss, was serving a sentence for perjury in connection with alleged spying for Soviets. Apparently, a similar plot was attempted against Hiss but he was protected by his criminal friends.

Hiss taught several prisoners to read and write. G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004), has pointed out: "Hiss... was an instinctive and habitual altruist. He liked helping people in need, even if the help imposed burdens on him. Caring about, and helping others, reinforced his sense of his own powers." Hiss actually told his son, Tony Hiss: "I like people when they are in trouble. Then they have to like you, and you can feel powerful by helping them." Even his great enemy, Whittaker Chambers, spoke of his "great gentleness and sweetness of character".

The journalist, Murray Kempton, says that Hiss was very popular in Lewisburg: "Hiss as an inmate was kind; he was helpful; he was indeed a comrade you could ask to hide your contraband and know he'd never either use it himself or hand it over to the guard." Meyer Zeligs claims that when Hiss was released from prison on 27th November, 1954, "there were rousing cheers from the bleak prison windows".

Alger Hiss: 1954-1970

Alger Hiss lost his license to practice law and his fear that "informal blackballing" would make it difficult for him to obtaining employment. As Alger later pointed out, that "Priscilla wanted us to flee the scenes of her torment. She suggested we change our names and try to get posts as teachers at some remote experimental school oblivious to public opinion." Hiss disagreed and wanted as much publicity as possible to show the world he had not given government secrets to the Soviets. As part of this campaign he published his memoirs, In the Court of Public Opinion (1957).

In 1957 Fred J. Cook was asked by Carey McWilliams, the editor of the Nation Magazine, to look into the Alger Hiss case. Cook replied: "My God, no, Carey. I think he's as guilty as hell. I wouldn't touch it with a ten-foot pole." Two weeks later McWilliams contacted Hiss again. "Look, I have a proposition to make you. I know how you feel about the case, but I've talked to a lot of people who I trust. They say if anybody looked hard at the evidence they'd have a different opinion. You're known as a fact man. Will you do this for me? No obligation. Will you at least look at the facts?"

Cook agreed and he later recalled that he changed his mind on the case after he examined the testimony of Whittaker Chambers. He later recalled: "Well, here was a guy who committed perjury so many times - admittedly so. I didn't see how anybody could trust anything he said. The typing process as he described it didn't make sense. Why would the Hisses spend all that time typing the documents when they supposedly had a whole system set up to photograph them? It was like that with the whole damn thing. When you looked at the government's case, it didn't make any sense down the line, anywhere. One after another as the arguments against Hiss fell apart, I realized I had been brainwashed by my own profession. Until then, I thought that if the story against him was generally accepted, then it had to be true. I should have known better, but I didn't."

Cook's article on Alger Hiss was published in Nation Magazine on 21st September, 1957. He argued that Hiss was a victim of McCarthyism and was not guilty of the accusations made by Whittaker Chambers who had accused Hiss of being a Soviet spy while working for the State Department. Hiss later commented: "It was the times. There was this great wave of hysteria about the great Russian communist menace, and I think the jury was susceptible to that. A lot of average people were. When you have an hysteria like that built in and bastards like Joe McCarthy are beating the drums, it affects the average person. They figure when there's smoke, there has to be fire."

Cook argued that both the FBI and HUAC had political reasons for victimizing Hiss. He also suggested that the FBI would have had the resources to build a typewriter with a typeface that appeared to match that of the Hiss family. Hiss, Cook concluded, might have been "an American Dreyfus, framed at the highest level of justice for political advantage". Cook's book on the case, The Unfinished Story of Alger Hiss, appeared in 1958.

In 1958 Priscilla Hiss asked her husband to leave the family home. Alger spent "the next several years in rented rooms and friend's apartments". However, when he became involved with another woman in the 1960s she refused to divorce him. Tony Hiss has pointed out that his mother "alternated between cursing Al for leaving and making plans for what she'd do after he came back."

Guilty or Not Guilty?

In 1971, the historian, Allen Weinstein, wrote an article where he argued that he was not convinced that Hiss was guilty, but doubted whether Hiss could be proven innocent given the evidence about the case that had thus far been made public. He suggested that a definitive understanding of the case would not be possible without the release of "the executive files of HUAC," "the relevant FBI records," and "the grand jury records." Weinstein contacted Hiss and he agreed for him to have access to his defense files. In 1972 he supported Weinstein's Freedom of Information suit to obtain FBI and Justice Department files on the case.

In the early 1970s Hiss was busy giving lectures at universities on his innocence. In 1972 the American Civil Liberties Union successfully challenged the ruling that made any government employee convicted of perjury in a case involving national security ineligible for a pension. The decision resulted in Hiss receiving 11 years' worth of back payments of his pension. In 1975 Hiss had his license to practice law in Massachusetts reinstated.

The journalist, John Chabot Smith published Algar Hiss: The True Story in 1976. In the book he argued that Hiss had been framed by Whittaker Chambers, who had typed the copies of the stolen documents himself. Smith claimed that in the spring of 1935 Chambers stayed at Hiss's "empty apartment" when it was "still full of its owner's furniture." Smith suggested that this included the Woodstock typewriter and therefore enabled him to use it to type up the stolen government documents."

William A. Reuben was probably Alger Hiss's greatest supporter. In 1974 he started his own campaign to persuade the FBI to release all the files on the Hiss case. David Remnick claimed that he had "devoted much of his adult life to vindicating Alger Hiss and clearing the Rosenbergs". Victor Navasky described Reuben as "to the left of Alger and just about everyone else" among Hiss's supporters, and suggested that if he had heard that on his deathbed Hiss had confessed to being a Communist and Soviet agent, he "wouldn't believe it."

In April 1976, the journalist, Philip Nobile, published an article on Alger Hiss in Harper's Magazine. He argued the prosecution's failure "to link Hiss to the actual typing of the documents" and "the lack of any witness supporting Chambers's party association with Hiss," Nobile felt, "troubled many open minds." Hiss told Nobile "the same old story of an unsound informer, forgery by typewriter, ruthless enemies of the New Deal, anti-Communist hysteria, and a poisoned jury." Nobile asked: "Why would he be peddling this tired line of defense... if it weren't true."

Nobile contacted 104 well-known individuals and asked them if they considered Hiss guilty or not guilty. Those who voted guilty were Sidney Hook, William F. Buckley, Clare Booth Luce, Dwight McDonald, Norman Podhoretz, John S. Service and Gary Wills. Those voting "not guilty" included Gus Hall, Abe Fortas, Lillian Hellman, Carey McWilliams, Arthur Miller, Victor Navasky and Robert Sherrill.

Allen Weinstein & Alger Hiss

Allen Weinstein began his investigation of Alger Hiss with the belief that he was innocent. Hiss agreed to cooperate with Weinstein in his attempts to obtain information from the FBI. As Weinstein pointed out: "Given the fact that I published an article which had argued for his innocence, and given the fact that... my premise was that he seemed to be innocent. Why not cooperate fully with me? I expected to be finding evidence that would help clear him."

The FBI refused to disclose these documents and so Weinstein concentrated on investigating Hiss's defense files. He discovered that his lawyer in the first perjury trial, Edward McLean (Debevoise, Plimpton and McLean) had doubts about his innocence. McLean believed that Priscilla Hiss was probably a Soviet spy and that Hiss was "at the very least, Alger was shielding Priscilla Hiss". His lawyers were concerned that he had originally lied about her membership of the Socialist Party of America. They were also convinced that she was fairly close to Whittaker Chambers. In February, 1950, Mclean withdrew from the case. William Marbury (Marbury, Miller and Evans) was also highly skeptical of Priscilla's evidence. Marbury was interviewed by Weinstein in 1974: "He (Marbury) had begun to have some very serious questions about the completeness of Hiss's account."

Weinstein also interviewed Meyer Schapiro, a close friend of Chambers (he had died in 1961). He confirmed that Chambers had a close association with Hiss. He was also with Chambers when he purchased a rug for Hiss in December 1936. Hiss had claimed that he had broken off his relationship with Chambers in 1935. Weinstein checked with the Massachusetts Importing Company that had sold the rug to Chambers and they agreed that the transaction took place in 1936.

After a legal struggle the FBI began releasing files on the Hiss case in October 1975. In February 1976 Weinstein told the New Republic that the files showed no evidence of an FBI conspiracy, only that the FBI had occasionally been inept or incompetent. Other documents released included the transcript of an interview with William Edward Crane, a FBI informant and a member of Chambers's network. He confirmed much of what Chambers had said about Hiss. Weinstein told the New York Times that "a preliminary look (at the declassified files) fails to bear out the most commonly raised conspiracy claims" against the FBI.

Allen Weinstein met Hiss in March 1976. He told him: "When I began working on this book four years ago, I thought that I would be able to demonstrate your innocence, but unfortunately, I have to tell you, that I cannot; that my assumption was wrong... I had a number of unresolved questions about Whittaker Chambers's testimony when I began. Even then I wasn't convinced that either of you had told the complete truth. I thought, however, that you had been far more truthful than Chambers. But after interviewing scores of people, looking at the FBI files, finding new evidence in private hands, and reading all of your defense files, every important question that had existed in my mind about Chambers's veracity on key points arose, and... none of them have been answered satisfactorily." Hiss replied: "I've always known you were prejudiced against me."

Weinstein's book, Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case, was published in the spring of 1978. Victor Navasky, the editor of Nation, made a bitter attack on Weinstein: "Whatever his original motives and aspirations, Professor Weinstein is now an embattled partisan, hopelessly mired in the perspective of one side, his narrative obfuscatory, his interpretations improbable, his omissions strategic, his vocabulary manipulative, his standards double, his corroborations circular and suspect, his reporting astonishingly erratic.... His conversion from scholar to partisan, along with a rhetoric and methodology that confuse his beliefs with his data, make it impossible for the non specialist to render an honest verdict in the case."

Alexander Cockburn published an article in Village Voice on 28th May, 1979, where he reported that Samuel Krieger had successfully sued Weinstein over his allegations in his book that he was a fugitive from arrest for a murder. "Weinstein's scholarship and research procedures have been plainly damaged by the whole Krieger affair." Weinstein argued that Chambers had recruited Samuel Krieger (alias Clarence Miller) into the American Communist Party. He then went onto say that Clarence Miller had escaped from jail in North Carolina in 1929 and became a fugitive in the Soviet Union. He wrote: "Krieger became an important Communist organizer during the Gastonia textile strike of 1929. After being jailed by local authorities, Krieger and several other union leaders fled to the Soviet Union." What the author did not know was that there were two communists using the name "Clarence Miller". It was the other one who fled to the Soviet Union. Krieger had admitted to being a Communist organizer but had been misidentified as a fugitive."

Death of Priscilla Hiss

Alger Hiss had been separated from Priscilla Hiss since 1958. In the early 1960s he began living with Isabel Johnson. She was a long-time socialist and had been romantically involved with Howard Fast and was married to screenwriter Lester Cole, one of the Hollywood 10. Alger's son, Tony Hiss, described her as "a tall, good-looking blonde".

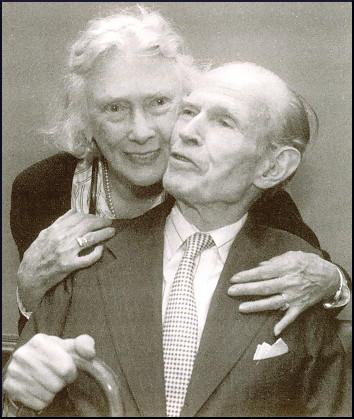

Priscilla refused to divorce her husband but on her death in 1984 Alger married Isabel. They moved to a house in East Hampton, on Long Island. She joined his campaign to have his conviction overturned and helped him write Recollections of a Life (1988). In 1986 when David Remnick interviewed Hiss for a feature story in the Washington Post Magazine, she "would say a quick hello" to him she "would not be interviewed or photographed."

Dmitri A. Volkogonov

In December 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the individual republics contained within it faced the prospect of becoming autonomous governmental units. The largest of these republics, Russia, seized the property of the former Soviet government, including the archives of the Communist Party. The following year Hiss wrote a letter to several Russian officials, seeking information about himself in former Soviet archives. In the letter he stated that he was 88 years old and wanted to die peacefully, and he asked for evidence that would confirm that he was "never a paid, contracted agent for the Soviet Union." He also told them he was sending his representative, John Lowenthal, to Moscow in a few weeks time.

Lowenthal met with General Dmitri A. Volkogonov, a Soviet official historian, in September 1992. Volkogonov arranged for Yevgeny Primakov, the head of Russia's Foreign Intelligence Agency, to search KGB archives. The following month Volkogonov presented Lowenthal with a letter stating that after examining "a great amount of materials... we have not found a single document... that substantiates the allegation that Mr. A. Hiss collaborated with the intelligence sources of the Soviet Union... Hiss... had never and nowhere been recruited as an agent of the intelligence services of the USSR and was never a spy of the Soviet Union." Volkogonov added: "The fact that Hiss was convicted in the 1950s was a result of either false information or judicial error... You can tell Alger Hiss that the heavy weight should be lifted from his heart."

This letter from Volkogonov made headline news in the United States. Hiss told the New York Times: "It's what I've been fighting for 44 years... I think this is a final verdict on the thing. I can't imagine a more authoritative source than the files of the old Soviet Union". He told the newspaper that he "rationally, I realized time was running out, and that the correction of Chambers's charges might not come about in my lifetime... but inside I was sure somehow I would be vindicated." Hiss also gave an interview to the Washington Post and used the opportunity to attack J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI at the time: "J. Edgar Hoover acted with malice trying to please various people who were engineering the Cold War."

However, Volkogonov came under attack from some leading experts on the KGB. The historian, Richard Pipes, pointed out that "there are a lot of things Volkogonov might not have seen... There are archives within archives... to say that that there was no evidence in any of the archives... was not very responsible." Alexander Dallin of Stanford University took a similar view, pointing out that "given the labyrinthine nature of the Soviet bureaucracy and the sensitivity of military and foreign intelligence operations... Volkogonov might have unknowingly overstated his findings."

Dmitri A. Volkogonov gave an interview in a Moscow newspaper in November 1992 that admitted that he had looked for only two days in the KGB archives for material on Alger Hiss. He pointed out that "what I saw gives no basis to claim a full clarification". Volkogonov went on to say that John Lowenthal had "pushed me hard to say things of which I was not fully convinced" and that he was aware that Hiss "wanted to die peacefully".

In the early 1990s several American academics were given access to KGB files. This included Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes. Their book, The Secret World of American Communism was published in 1995. The book was a collection of 92 documents from the 1930s and 1940s, with commentary by the authors. The documents consisted of communications between members of the American Communist Party and officials in Moscow. The authors argued that these documents conclusively demonstrated that the party's actions and policies were being directed by Joseph Stalin.

Klehr and Haynes were unable to find Hiss's name on any documents, they did find plenty of evidence to support the testimony of Whittaker Chambers. This included the information that Joszef Peter was the controller of the American Communist Party's secret apparatus between 1932 and 1938. In his book, Witness (1952), Chambers had argued: "The Soviet espionage apparatus in Washington also maintained constant contact with the national underground of the American Communist Party in the person of its chief. He was a Hungarian Communist who had been a minor official in the Hungarian Soviet Government of Bela Kun. He was in the United States illegally and was known variously as J. Peters, Alexander Stevens, Isidore Boorstein, Mr. Silver, etc. His real name was Alexander Goldberger and he had studied law at the university of Debrecen in Hungary."

The Death of Alger Hiss

Tony Hiss has claimed that by 1995 Alger Hiss's body was "almost completely worn out" making him "a prisoner of his own physical frailties." In March 1996, Hiss was distressed when the newspapers carried stories of a cable that that had been sent by Anatoli Gromov, on 30th March, 1945, had been intercepted by the National Security Agency (NSA). Gromov was the controller of Washington-based NKVD agents. The cable included details of a conversation that had taken place between Iskhak Akhmerov and an agent with the codename Ales. The cable claimed that Ales had worked for the Neighbors (GPU) since 1935 and that he had been to the Yalta Conference and afterwards visited Moscow. An analyst at the NSA had written on 8th August, 1969, that Ales was "probably Alger Hiss".

Eric Breindel, writing in the Wall Street Journal, described the cable as "the smoking gun in the Hiss case". He went on to argue: Folks who refuse to recognize this document's implications, are likely to be the sort who would insist on Mr. Hiss's innocence even if he confessed." Hiss was contacted by journalists but he was too ill to be interviewed. However, his son Tony, denied his father was "Ales" and had only spent a brief time in Moscow after the Yalta Conference.

Alger Hiss died on 15th November, 1996. Evan Thomas, writing in Newsweek, suggested that Hiss "probably was a Soviet spy" and that in protesting his innocence he "was just a very good spy, deceitful to the end." However, some commentators, such as Peter Jennings on ABC News, had concentrated on the early statements of Dmitri A. Volkogonov, claiming that he had been vindicated by the Russians. Robert Novak pointed out that Volkogonov had retracted his statement and referred to a "deep-seated reluctance within the American liberal establishment to acknowledge that Hiss was a liar, spy, and traitor."

George Will, writing in the Washington Post, denounced Hiss and his supporters: "Alger Hiss spent 44 months in prison and then his remaining 42 years in the dungeon of his grotesque fidelity to the fiction of his innocence. The costs of his unconditional surrender to the totalitarian temptation was steep for his supporters. Clinging to their belief in martyrdom in order to preserve their belief in their "progressive" virtue, they were drawn into an intellectual corruption that hastened the moral bankruptcy of the American left."

Historians and the KGB Archives on Alger Hiss

In 1999 Allen Weinstein published The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America. He had spent several years examining the KGB archives and came across a considerable amount of material that showed Alger Hiss was a Soviet spy. This included a memorandum sent by Hede Massing, a Soviet spy based in New York City, to Moscow. It concerned her attempts to recruit Noel Field. According to Massing's report he had been recently approached by Alger Hiss just before he left to attend a conference in London: "Alger Hiss (she used his real name because she was unaware of his codename) let him know that he was a Communist, that he was connected with an organization working for the Soviet Union and that he knew Ernst (Field) also had connections but he was afraid they were not solid enough, and probably, his knowledge was being used in a wrong way. Then he directly proposed that Ernst give him an account of the London conference."

Hede Massing continued in the memorandum how another spy in the network, Laurence Duggan, was being involved: "In the next couple of days, after having thought it over, Alger said that he no longer insisted on the report. But he wanted Ernst to talk to Larry and Helen (Duggan) about him and let them know who he was and give him (Alger Hiss) access to them. Ernst again mentioned that he had contacted Helen and Larry. However, Alger insisted that he talk to them again, which Ernst ended up doing. Ernst talked to Larry about Alger and, of course, about having told him 'about the current situation' and that 'their main task at the time was to defend the Soviet Union' and that 'they both needed to use their favorable positions to help in this respect.' Larry became upset and frightened, and announced that he needed some time before he would make that final step; he still hoped to do his normal job, he wanted to reorganize his department, try to achieve some results in that area, etc. Evidently, according to Ernst, he did not make any promises, nor did he encourage Alger in any sort of activity, but politely stepped back. Alger asked Ernst several other questions; for example, what kind of personality he had, and if Ernst would like to contact him. He also asked Ernst to help him to get to the State Department. Apparently, Ernst satisfied this request. When I pointed out to Ernst his terrible discipline and the danger he put himself into by connecting these three people, he did not seem to understand it."

In a review of Weinstein's book, Thomas Powers argued: "Much additional evidence about Hiss's involvement with the Soviets has turned up since the voluminous and explicit claims by Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley in the 1940s, claims which no serious scholar of the subject any longer dismisses... while the excesses of McCarthyism may be fairly described as a witch hunt, it was a witch hunt with witches, some in government.... What Whittaker Chambers had claimed was true, and it was convincingly and obviously true by the time Hiss went to jail for perjury. Hiss's denial, and his persistence in it for decades, and his support in it by so many otherwise smart people, was one of the great intellectual contortion acts of history. The evidence now... is simply overwhelming."

Powers went on to ask the question: "What continues to astonish and bewilder me now is why Hiss lied for fifty years about his service in a cause so important to him that he was willing to betray his country for it. The faith itself is no problem to explain: hundreds of people shared it enough to do the same thing, and thousands more shared it who were never put to the test by a demand for secrets. But why did Hiss persist in the lie personally? Why did he allow his friends and family to go on carrying the awful burden of that lie?"

G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004), attempts to answer this difficult question: "Alger Hiss can no longer be seen as a figure of ambiguity. This is so even though his psychological makeup was highly complex, and his motivation resists easy characterization. The ambiguity associated with Hiss was created by his regularly asserting things about himself and his life that were not true, and by others - for their own ideological reasons and because of Hiss's extraordinarily convincing persona - choosing to believe them.... In short, many Americans found qualities in Hiss they could identify with or admire. And many found qualities in Hiss's antagonists that, retrospectively, they found distasteful. The anti-Communism of the Cold War era appeared to many as simple-minded and repressive. Richard Nixon demonstrated that becoming president of the United States did not divest a person of mean-spiritedness and a lack of principles. J. Edgar Hoover's carefully constructed image as a virtuous G-man came apart under closer scrutiny. When one totaled up Hiss's favorable associations and the notoriety of his enemies, his continued professions of innocence took on to some an air of nobility."

Primary Sources

(1) Alger Hiss, Recollections of a Life (1988)

As with the vivid color differences of my initial recollections, the separate roles of Aunt Lila and my mother were always clear. There was no confusion as to their household functions. My mother was in charge. Lila was her assistant, an assistant whose help was pretty much limited to being a companion for the children.

My father had been an executive of a large wholesale dry-goods firm, a man overwhelmed by financial and family worries. Suicide was a blow that was shameful as well as tragic for any family in those years, and mine reacted to the shame by silence. I did not know that my father had taken his own life until I was about ten years old and I overheard the remark of a neighbor sitting on her front steps talking with another neighbor. As my younger brother and I passed by, we heard her say, "Those are the children of the suicide."

Donald and I had been shielded from the shameful act; there was not even a hint of a family secret. The solicitude of relatives and friends for my immediate family was demonstrated in part by their reticence. The tragedy that had overwhelmed the household had been relegated to the sphere of nonexistence. Consequently, I was angered by the callous remark that I believed to be false and insulting. It remains one of my most painful and indelible memories.

On the whole, however, my childhood memories are of a lively and cheerful household, full of the bustle of constant comings and goings. The shock of learning by accident of my father's suicide was lessened by the warm family spirit I remember so well. Donald and I went immediately to Bosley, as our confidant. We wanted to protect our mother from the ugly remark, for we of course accepted the then prevailing view of suicide. But, to our consternation, Bosley did not share our disbelief and anger. Instead, like the journalist he later became, he went to the offices of the Baltimore Sun and examined old copies of the paper. He then solemnly confirmed the report we had so vigorously rejected.I recognized that my mother and the other adults in my life had known of the suicide, but somehow I did not feel resentment at having been kept in the dark. Once I had learned the adult secret, I joined in the family policy of silence. I must have felt that if my mother wouldn't talk to me about it, neither should I talk about it within the family. It was years before I mentioned my father's suicide to anyone but Donald, and even we spoke of it rarely.

I certainly never broached the subject to Aunt Lila, though in many ways I was closer to her than I was to my mother. This may have been partly due to my mother's being the family magistrate, although her severest punishment was a slap with a ruler on the palm of an extended hand. When I went to my mother for solace of a hurt, I was likely to receive a homily on how best to get on in the world. In contrast, Aunt Lila could be counted on for sympathetic understanding. My mother's fortitude in adversity was magnificent, but she was not cut out for the role of confidante. My father had left her our house and a modest income, which she used to raise and educate us all. One of her duties, she felt, was to prepare us for our role in life. Conventional in her values, she was ambitious for our success in a material sense.

Aunt Lila wanted something different for us, something less worldly. She wanted us to share her love of literature, her respect for learning and morality. But she was not preachy, so that her wishes were never just words of advice. I felt I had an ally in her, if a silent one, when I resisted my mother's favorite admonition: "Put your best foot forward." Long before I read Henry James, I was suspicious of the bitch goddess Success. And in retrospect, I can see that Aunt Lila's persistent commitment to things of the spirit gave a nice balance to my mother's emphasis on the importance of life's practical demands.

My clearest recollections of Aunt Lila are of her reading aloud to us. She began this practice before I was old enough to be an orderly member of her audience. This was a carryover of a familiar nineteenth-century American custom. She read in a clear, conversational tone. Yet her readings were a performance, a festive occasion, and perhaps it was here that my lifelong love of the theater began. Lila's audience often included friends of my older siblings and sometimes adults. When the girls went away to college, we boys continued to receive the rich benefits of Aunt Lila's reading and other literate gifts.

(2) Murray Kempton, New York Post (22nd April, 1978)

The Hisses were not a distinguished family run down. in his final tragedy, his friends and enemies would join in exaggerating the nobility of his origins. When disaster came to him, he was listed in the Washington Social Register, but his mother was not in its Baltimore edition.

Alger Hiss's father was a wholesale grocer; he committed suicide when Alger was nine. His older brother was a bohemian who died young. They lived near Lanville Street, which is the heart of shabby gentility in Baltimore. As he grew up, more substantial families around him were moving out into the suburbs. The Hisses stayed there in a neighborhood slowly running down. They were not a family of special social prestige, but the Baltimore in which Alger Hiss grew up had its own corner for the sort of family that... rested on that border between respectability and assured position. In the circumstances of her life, society felt a particular sympathy for Alger Hiss's mother.... In a family like this one.... it was better to be a boy than a girl, if only because Baltimore needed more boys than girls at debutante

parties.

(3) Denise Noe, Alger Hiss (2007)

Alger Hiss was born in 1904, the fourth of five children in an upper-middle-class Presbyterian family in Baltimore. The Hiss family was financially comfortable but emotionally troubled. When Alger was only two years old, his father committed suicide by cutting his throat with a razor. When Alger was 25, his sister Mary Ann committed suicide by drinking a household cleanser. Hiss’s older brother Bosley, died when he was in his early twenties of Bright’s disease, a kidney disorder aggravated by Bosley’s overindulgence in alcohol.

As a young man, the slim, handsome, and dapper Alger impressed most people as self-confident and more than a few as arrogant. He appeared to have avoided the depression that afflicted other members of his family and achieved success at a young age. Hiss graduated from John Hopkins University in 1926. While there, he shone both academically and in extracurricular activities. He was a Phi Beta Kappa, a cadet commander in ROTC, and was voted “most popular student” by his graduating class.

(4) Alger Hiss, Recollections of a Life (1988)

When I was a student at the Harvard Law School, from September 1926 until June 1929, Felix Frankfurter was far and away the most colorful and controversial member of the faculty. Brilliant and irrepressible, he was much more than a campus figure. His innumerable close friendships with leaders all over the country and abroad had already made him a man of national prominence by the time I was his student.

He was always conspicuous, despite his small stature, as he moved about the campus. This was because as he bounced along-short, dynamic, articulate - he was invariably surrounded by a cluster of students. Frankfurter was always teaching, in class and out. His didactic style was challenging, even confrontational. He invited discussion and he reveled in sharp exchanges. These continued after class had ended.

But Frankfurter was not popular with the majority of his students or his fellow faculty members. In both cases the reasons, I believe, were the same.

Frankfurter was cocky, abrasive, and outspoken. His style was simply not theirs. In addition, Frankfurter was the leader of the liberal wing of the faculty. Most of his older colleagues were politically conservative, as were most of the students.

The great legal scholar Dean John H. Wigmore of the Chicago Law School was among Frankfurter's opponents in the dispute over the Sacco and Vanzetti case, calling Frankfurter with distaste a "plausible pundit" - fighting words in the mannerly decorum of academia in those days. A stout civil libertarian, Frankfurter was a vigorous champion of the innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti, right up to their execution in the summer of 1927 and afterward. He participated actively in groups formed to aid them, and he spoke and wrote tirelessly in their behalf. Frankfurter and those who shared his views were shocked at what they considered glaring errors in the conduct of the trial by the prosecutor-errors uncorrected, and indeed compounded, by the judge. Prejudice had run high against the defendants as Italians and as anarchists, and Frankfurter was outraged by instances where prejudice affected the conduct of the case. It raised questions about the fairness of Massachusetts justice, polarized opinions in that state, and aroused strong feeling throughout the nation and the western world.