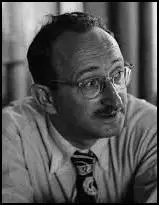

Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook, the son of Isaac and Jennie Hook, was born in Brooklyn on 20th December, 1902. His parents were Austrian Jewish immigrants and they lived in Williamsburg: "The Williamsburg area of Brooklyn, before World War I, was a slum of checkered ethnic pattern - Irish, Italian, German, Jewish, with a scattering of East and Southeastern European families. The ethnic areas were largely enclaves separated from other ethnically related groups. To travel from one Jewish enclave to another, a short mile away, one had to go through an Italian enclave or an Irish one, depending on the direction. Public School 145 was in an Irish-German district, and those of us who lived on Bushwick Avenue above Flushing or below Myrtle not infrequently had to fight our way through. Going to school was not very hazardous, because we could time ourselves to arrive early, just after the Irish and German boys left their neighborhoods. Returning was more difficult, because the little toughs to whom we were outsiders - Sheenies they called us - would hurry home to prepare for us, with snowballs in winter and rocks at other times. We often outmaneuvered them by taking circuitous routes home or by traveling in packs ourselves."

Hook's family lived in extreme poverty. He explained in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The physical conditions under which we lived were quite primitive. On Locust Street where we lived for some years, the toilets were in the yard. In other tenements they were shared with another family. All were railroad flats, heated only by a coal stove and boiler in the kitchen. Gas provided illumination and the most common means of suicide. We froze in winter and fried in summer. Vermin were almost always a problem, and the smell of kerosene pervaded our bedrooms, which had no windows and gave on skylights instead. The public baths were used until bathtubs were installed. The women worked like pack horses; their work was never done. Nor could their husbands have shared their household labors. My father left for work before we arose; he returned from work when we were ready to go to bed. More than once, to the astonishment and amusement of the children, he would fall asleep at the dinner table with the soup spoon in his hand poised in the air."

Early Education

Sidney Hook did not enjoy his early education: "Although the public schools were religiously attended (children feared the wrath of their parents much more than the threats of the truant officer), the classroom experience was far from enjoyable. First of all, the discipline was exacting. Our teachers were little more than martinets. We had to sit erect, with our hands clasped on the edge of the desks or folded behind our back, in absolute silence. Everything was done at command, according to a rigorous and rigid schedule. Even the occasional interesting lesson would be broken off when the allotted time was up, no matter how eager the students were to continue. The slightest infraction of proper conduct -a whisper, a paper dropped on the floor, a shove, a pinch, or the dipping of a girl's braid in the open inkwell-evoked withering sarcasm, denigrating scolding, and corporal punishment-whacks with the twelve-inch ruler on open extended palms, and whacks with the heavy ferule on the rump. Only the boys got the latter treatment, which was more humiliating than painful.... To most of us the boredom was worse than the discipline. The dreary drill seemed directed to the dullest in the class... So little was there to relieve the intellectual boredom - ocasionally a spelling bee or an improvised story - that I would often go to bed praying that the school would burn down before morning. Life in the classroom-perhaps it would be more accurate to say the absence of life-accounted for it."

At the age of 13 Sidney Hook became a socialist. He was introduced to the ideas of Eugene Debs by a schoolmate whose father "had imbued his son with an enthusiasm that bordered on the fanatical". As a result of this friendship Hook became a "faithful reader" of the New York Socialist Call newspaper. Hook also read pamphlets written by Daniel DeLeon. However, the most important influence at the time was the work of the novelist, Jack London: "The most profound source of the Socialist appeal, was its moral concern, its sense of human fraternity, its emphasis upon equality of opportunity for all, its view that what men have in common - their human condition in life and death - was more significant than the racial, national, and other parachial differences that separated them."

In February 1916, Hook entered Brooklyn Boys High School. "At that time it was renowned for its rigorous scholastic standards and enjoyed the same reputation among secondary schools as City College did among institutions of higher learning. It was a good forty-five minute walk from the Williamsburg slum in which we lived." However, he was disappointed by the standard of education offered by the school: "The pedagogy was execrable. The textbook was the only authority, and except in some classes where problems were studied (mathematics and physics), excellence in scholarship depended upon the students' ability to regurgitate it. The all-male teaching faculty, for the most part, knew little about methods of teaching, brooked no contradiction from students, and were even impatient of questions. Instruction was not geared to broadening the interests and liberalizing the minds of the students but to the passing of examinations, especially the Regents' tests. I do not recall a single class that ended on a problem whose resolution we were moved, or ever urged, to think about. The teaching was not only authoritarian but conducted in a spirit of hostility, aimed at detecting an unprepared student and correcting him if he was out of line with respect to even trivial details. The result was that for many students, among them the best, outwitting the teacher became more challenging than mastering the lesson."

First World War

Hook was totally opposed to the United States involvement in the First World War and the Espionage Act that was passed by Congress in 1917. It prescribed a $10,000 fine and 20 years' imprisonment for interfering with the recruiting of troops or the disclosure of information dealing with national defence. Additional penalties were included for the refusal to perform military duty. Over the next few months around 900 went to prison under the Espionage Act. Criticised as unconstitutional, the act resulted in the imprisonment of many of the anti-war movement. This included the arrest of left-wing political figures such as Eugene V. Debs, Bill Haywood, Philip Randolph, Victor Berger, John Reed, Max Eastman, Martin Abern and Emma Goldman.

Soon after the outbreak of war Hook and the rest of his class was asked to write an essay entitled "Love of Country". His opening sentence was: "Love of country is often deterimental and derogatory of the process and advancement of civilization." His teacher, Mr. Buttrick, was furious and ordered him from the class. Soon afterwards the teacher tried to get Hook expelled for not singing The Star-Spangled Banner. Hook was also in trouble with his history teacher, Mr. Grimshaw, when he claimed that The Lusitania had been carrying munitions of war. According to Hook he "dashed over to my desk, stood over me with bared fist" and shouted, "I dare you to repeat that lying piece of German propaganda!"

Hook was also a supporter of the Russian Revolution. He did not agree with the closing down of the Consit and the banning of the opposition parties but as he explained: "The first doubts began to emerge only after the Russian October Revolution, when the voices of Menshevik and Anarchist protest reached us, but only faintly. These voices and our doubts were drowned out by the thunder of the counterrevolutionary armies of Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, and the remarkable propaganda of the Bolsheviks, whose mastery of all the media of modern communication has remained unsurpassed from that day to this."

Harry Overstreet

In 1919 Hook began studying philosophy at the College of the City of New York. His main lecturer was Harry Overstreet who had been influenced by the teaching of John Dewey. "Professor Harry Overstreet, chairman of the Department of Philosophy... had been converted to John Dewey's conception of philosophy, but unfortunately he did not hold up his end of the technical arguments when challenged by philosophy students... Nor was he highly regarded by fanatical young Socialists, to whom he was a mere social reformer whose ineffectual programs made more difficult the radicalization of the working class."

Hook was impressed by the character of Overstreet. Hook recorded in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "Harry Overstreet was a man of an extraordinarily sweet and generous disposition. He had genuine dramatic talent that enabled him to personalize the situations and problems out of which the conflict of human values developed. During his sabbatical year, he had worked anonymously as an unskilled laborer in a Midwest factory and was one of the first persons who tried to come to grips with a problem that only decades later became central in discussions of social philosophy. This was the nature of work in any industrial society and the difficulties of achieving self-fulfillment in tending the assembly lines of mass production. Unfortunately he could not do justice to his own insights, but instead entertained us with autobiographical tidbits and vivid accounts of his own family life and the difficulties of growing up."

Overstreet was strongly opposed to the policies of A. Mitchell Palmer, the recently appointed as attorney general. Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. His view was reinforced by the discovery of thirty-eight bombs sent to leading politicians and the Italian anarchist who blew himself up outside Palmer's Washington home. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

Red Scare

Hook later recalled how Harry Overstreet reacted to what became known as the Red Scare: "Overstreet would flare up with an eloquent outburst of denunciation at some particularly outrageous act of oppression. This was especially hazardous during the days of the Palmer raids and subsequent deportations. There were few organized protests against these brutal highhanded measures that crassly violated the key provisions of the Bill of Rights. The general public reacted to the excesses as if they were a passing heat wave. In the postwar hysteria of the time, it seemed as if the public either supported these measures or, more likely, was indifferent to them."

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

Hook pointed out in his autobiography: "The general public reacted to the excesses as if they were a passing heat wave. In the postwar hysteria of the time, it seemed as if the public either supported these measures or, more likely, was indifferent to them. One case that moved me profoundly was that of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Goldman and Berkman had been unjustly convicted on the flimsiest evidence of conspiring to prevent young men from registering for the draft. What they had done was merely to express their opposition to conscription, which they had every right to do. After a caricature of a trial, they were sentenced to two years in jail, heavily fined, and ordered deported to Russia, from which they had emigrated as children, at the expiration of their sentence. The case against these truly noble idealists, whose chief failing was an incurable naivete, should have been thrown out of court. The day the S.S. Buford sailed with them and 239 others on board was one of the darkest days of my life. Several days after the Buford left port, Professor Overstreet, in a large lecture section, made an impassioned reference to the Buford as the Ark of Liberty on the high seas. A hush fell over the class. Suddenly a student known to us for his right wing sentiments rushed from the room. In the atmosphere of the moment, we were convinced that he was reporting Overstreet's subversive utterance to someone in authority."

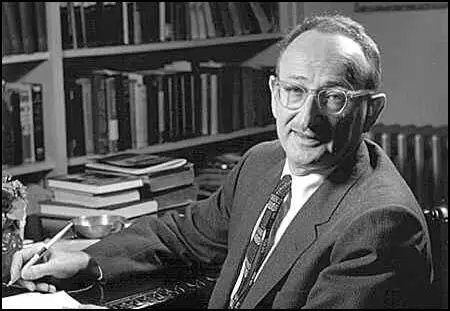

Morris Cohen

Hook was also deeply influenced by the teaching of Morris Cohen. He explained in Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "One of the great teachers of the first third of our century was Morris R. Cohen of the College of the City of New York, where he taught courses in philosophy from 1912 to 1938. By conventional pedagogical standards, he would not be considered a great or even a good teacher, for he inspired only a few of his students to undertake careers in philosophy and overawed the rest. Nonetheless his prowess as a teacher became legendary and his ideas a force in the intellectual community. Yet his classroom techniques would never have won him tenure in any public school system, and he himself confessed he was a failure in his early efforts as an elementary and secondary schoolteacher, because he could not even control his classes."

Sidney Hook explained how Cohen used the Socratic method in his teaching: "During the years I studied with Morris Cohen, he used it with devastating results in the classroom. If a problem was being considered, Cohen would deny it was a genuine problem. When he restated the problem, every answer to it was rejected as vague or confused or ill informed if not contrary to fact, or as leading to absurd consequences when it was not viciously circular, question-begging, or downright self-contradictory. The students' answers, to be sure, were almost always what Cohen said they were while he dispatched them with a rapier or sledgehammer - and usually with a wit that delighted those who were not being impaled or crushed at the moment. Cohen enjoyed all this immensely, too. There was no animus in this ruthless abortion of error, of stereotyped responses, and of the cliches and bromides that untutored minds brought to the perennial problems of philosophy, and although the students soon felt that whatever they said would be rejected, they consoled themselves with the awareness that almost everyone was in the same boat. When they were not bleeding, they enjoyed watching others bleed. Occasionally Cohen would let up on a student who had the guts and gumption to answer back. If, ignoring the laughter of his fellows, he insisted on his point in the face of Cohen's mounting impatience, that student was subsequently treated more gingerly. Or when Cohen had the answer to a moot point - an answer he was holding in reserve to trot out after he had gone through the class, beheading one student response after another - he would occasionally skip the student who he suspected might supply the answer. Some of us who felt the call of philosophy and had avidly read Cohen's published articles could sometimes anticipate what he had in mind. He let us alone in class, but we had our egos properly pinched in private sessions with him."

Hook admitted that Cohen was often cruel to students: "Looking back on those days and years, I am shocked at the insensitivity and actual cruelty of Cohen's teaching method, and even more shocked at my indifference to its true character when I was his student. I was among those who spread the word, in speech and writing, about his inspiring teaching and helped make him a legendary figure who was judged and admired for his reputation rather than his actual classroom performance. Only when I myself became a teacher did I realize that the virtues of his method could be achieved without the browbeating, sarcasm, and absence of simple courtesy that marked his dialectical interrogations. It is true that he inspired me as well as others. He was the first teacher to command my profound intellectual respect and the first to greet my opposition to America's entry into the war and my questioning with anything other than the ferocious antipathy of my high school and City College teachers. Toughened as I was as a street brawler and political activist, I thoroughly enjoyed our give and take - although I almost always took more than I gave. Yet he needlessly hurt too many others in what was for him a form of theater. His religion, his accent, and his irascibility denied him an opportunity to teach in the graduate school of a great university. That is where he really belonged and where the challenge of mature minds would have enabled him to fulfill what he professed was his overwhelming desire-to pursue systematic philosophy. He compensated for the bitterness and deprivation of his lot by playing God in the classroom."

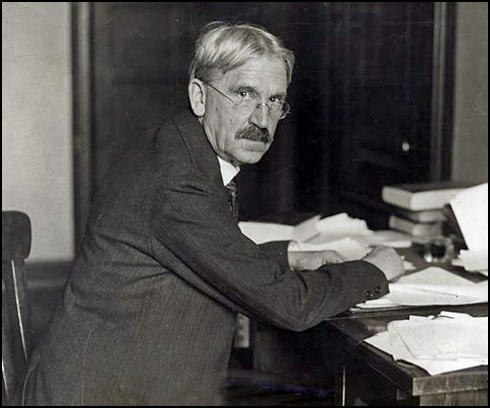

John Dewey

While at university Hook became a devoted follower of John Dewey. "My familiarity with Dewey's writings began at the College of the City of New York. I had enrolled in an elective course in social philosophy with Professor Harry Overstreet, who was a great admirer of Dewey's and spoke of him with awe and bated breath. The text of the course was Dewey's Reconstruction in Philosophy, which we read closely. Before I graduated, and in connection with courses in education, I read some of Dewey's Democracy and Education and was much impressed with its philosophy of education, without grasping at that time its general significance... What did impress me about Reconstruction in Philosophy, and later other writings of Dewey, was the brilliant application of the principles of historical materialism, as I understood them then as an avowed young Marxist, to philosophical thought, especially Greek thought. Most Marxist writers, including Marx and Engels themselves, made pronouncements about the influence of the mode of economic production on the development of cultural and philosophical systems of thought, but Dewey, without regarding himself as a Marxist or invoking its approach, tried to show in detail how social stratification and class struggles got expressed in the metaphysical dualism of the time and in the dominant conceptions of matter and form, body and soul, theory and practice, truth, reason, and experience. However, even at that time I was not an orthodox Marxist. Although politically sympathetic to all of the social revolutionary programs of Marxism, and in complete agreement with Dewey's commitment to far-reaching social reforms, I had a much more traditional view of philosophy as an autonomous discipline concerned with perennial problems whose solution was the goal of philosophical inquiry and knowledge.... In that period he was indisputably the intellectual leader of the liberal community in the United States, and even his academic colleagues at Columbia and elsewhere who did not share his philosophical persuasion acknowledged his eminence as a kind of intellectual tribune of progressive causes."

Although he was impressed by Dewey's writing he had doubts about his teaching style: "A student wandering into a class given by John Dewey at Columbia University and not knowing who was delivering the lecture would have found him singularly unimpressive, but to those of us enrolled in his courses, he was already a national institution with an international reputation - indeed the only professional philosopher whose occasional pronouncements on public and political affairs made news... As a teacher Dewey seemed to me to violate his own pedagogical principles. He made no attempt to motivate or arouse the interest of his auditors, to relate problems to their own experiences, to use graphic, concrete illustrations in order to give point to abstract and abstruse positions. He rarely provoked a lively participation and response from students, in the absence of which it is difficult to determine whether genuine learning or even comprehension has taken place. Dewey presupposed that he was talking to colleagues and paid his students the supreme intellectual compliment of treating them as his professional equals. Indeed, if the background and preparation of his students were anywhere near what he assumed, he would have been completely justified in his indifference to pedagogical methods. For on the graduate level students are or should be considered junior colleagues, but when they are not, especially when they have not been required to master the introductory courses, a teacher has an obligation to communicate effectively. Dewey never talked down to his classes, but it would have helped had he made it easier to listen."

Elementary School Teacher

On 9th April, 1923, Sidney Hook began teaching in the elementary school system in New York City. "Compared to the most recent disciplinary cases in our ghetto or slum schools, these students were only mildly disorderly. The drug scene was still many years in the future, and although many carried vicious pocket knives honed to razor-sharp thinness, the switchblade had not yet come into use. Half of the class seemed genuinely dull or backward, half were quick-witted but restless and undisciplined. Although most were native-born, their use of English was extremely primitive.... The students feared their parents and the truant officer more than their teacher, and came up with all sorts of original ailments and domestic calamities to win freedom from classroom attendance. They were safe so long as the teacher did not report excessive absence."

Hook did not find it too difficult to control his students: "The times today are so different that no instructive comparison can be drawn between the school scene then and now. Physical punishment of the boys was permitted for severe infractions of discipline, but I never heard of physical assaults against teachers on school premises. The family structures were intact, and there was no punishment more fearful to the students than a threat to summon their parents to school. Because the very dull and the very disruptive were removed from the ordinary classes, there was little interference with the educational process, and although I had no difficulty in keeping my opportunity class orderly, I believe I was able to teach them something, too. This was rendered easier by the fact that the class consisted of boys who, for the most part, had not reached full pubescence. Moreover, a rumor (resulting from some misunderstood remarks of mine, which I did not contradict) began to circulate that I was an amateur pugilist, and this impressed them."

Hook adopted the progressive methods of teaching that was promoted by John Dewey. " But the most important cause of my success was my ability to motivate the students, to build on their interests, and to capture and hold their attention by dramatizing events in history. To do this I had to disregard the syllabus for the grade. Capitalizing on the boys' passion for baseball, I taught them percentage, so that they could determine the standing of the clubs and the batting averages of the players, as well as American geography. They learned a great deal about the colorful historical figures of the past and present.... I followed progressive methods, not out of principle but because they actually worked. I was unorthodox even in my untimely progressivism. There were some skills that could only be acquired by drill, and one couldn't always make a game of them. I was not above resorting to external rewards for persistence in drill exercises."

Sidney Hook taught at the College of the City of New York. He also studied for his Ph.D. degree at Columbia University under John Dewey. "He (John Dewey) was world famous when I first got to know him, but he didn't seem to know it. He was the soul of kindness and decency in all things to everyone, the only great man whose stature did not diminish as one came closer to him. In fact it was difficult to remain in his presence for long without feeling uncomfortable... He was too kind, kind to a fault... There was an air of abstraction about Dewey that made his sensitivity to others surprising. It was as if he had an intuitive sense of a person's authentic, unspoken need. Anyone who thought he was a softie, however, would be brought up short. He had the canniness of a Vermont farmer and a dry wit that was always signaled by a chuckle and a grin that would light up his face."

Weimar Germany

Hook was awarded a fellowship by the Guggenheim Foundation for research on post-Hegelian philosophy. He sailed for Germany in June 1928. Hook was shocked by the level of anti-Semitism and nationalism in Weimar Germany: "The phenomenon of anti-Semitish was not what impressed me most. It was rather the pervasiveness and the intensity of the spirit of nationalism, not only among all political groups including the Communists, but among all elements of the population I came in contact with. Only some segments of the Social Democrats were free of this nationalist spirit. It was, for many, more of an aggrieved and defensive nationalism than of a chauvinistic kind. The Germans, I was told again and again, had been deceived by Wilson's Fourteen Points with their call for no annexations and no reparations. Whether out of ignorance or naivete, many seemed to believe that it was not because of a shattering military defeat that Germany had sued for peace, but because of the promise of those Fourteen Points. Every provision of Wilson's declaration had been violated by the Treaty of Versailles, which also contained-mention of this would always rouse an audience to fury-the humiliating clause that Germany bore sole guilt for the war. Among the many mistakes the civilian leaders of the Weimar Republic made, the most disastrous was signing the treaty. They should have insisted that the German generals who had lost the war acknowledge it formally before the eyes of the world. Failing that, it would have been better if they had not put their names to it at all."

While in Germany he became friends with Karl Korsch: "Politically, the most interesting of the individuals I got to know was Karl Korsch. A leaflet advertising one of his public lectures, distributed at a tavern, provoked my curiosity. He was a man of dynamic enthusiasm and dedicated to the proposition that both Social Democratic and Communist orthodoxy had betrayed the essence of scientific Marxism. He himself had participated in the Communist uprising in Thuringia while he was teaching at the university there, had fled when it was defeated, and after a general amnesty coolly reappeared to take up his post. The upshot of the resulting scandal was an arrangement with the local government, according to which he would be paid his salary on condition that he did not teach. His emphasis upon the element of activity in Marx's theory of knowledge and the indispensability of judgments of value and practice (contra Rudolf Hilferding's and Karl Kautsky's views) were directly in line with my own pragmatic interpretation of Marx and the synthesis I was then trying to establish between Dewey and Marx. Korsch was at home in English, and after we exchanged reprints of some of our published writings, we became very friendly."

Sidney Hook also met with Eduard Bernstein who talked about Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling: "Because of my Guggenheim project, I made several efforts to arrange a meeting with Eduard Bernstein, the famous revisionist of Marx, then living in retirement. His figure and outlook, in the perspective of the fifty years after Marx's death, had grown enormously. I was put off several times, and when I finally met him, I realized why. He was suffering from advanced arteriosclerosis and was attended by a nurse. He seemed at first reluctant to talk about his reminiscences of Marx, but at the outset of our talk, to my chagrin, was eager to describe his first day at school, about which he had very vivid memories. I kept reverting to various episodes of Marx's life and to some of Marx's literary remains, which Engels had entrusted to Bernstein. His manner was benign and friendly. Only twice did he lose his composure and burst out with a stormy lucidity. The first time was when I mentioned Edward Aveling with whom Eleanor Marx, Marx's youngest daughter, had been enamored, and who had been the cause of her suicide. Bernstein rose from his chair with flushed face and agitated tone and voice and denounced him as an arch scoundrel. I did not, however, get a very coherent account of Aveling's infamy."

Soviet Union

In 1929 Hook visited the Soviet Union: "Although I became aware of definite shortcomings and lacks in Soviet life, I was completely oblivious at the time to the systematic repressions that were then going on against noncommunist elements and altogether ignorant of the liquidation of the so-called kulaks that had already begun that summer. I was not even curious enough to probe and pry, possibly for fear of what I would discover. To be sure, most of the politically knowledgable persons I met were Communists of varying degrees of fanaticism. Although the deadly purges of the Communist ranks had not yet begun, I was aware that followers of Trotsky were having a hard time of it. Adolf Joffe's letter of suicide - he was a leading partisan of Trotsky - protesting his treatment and that of others at the hands of the Party bureaucracy had moved me deeply, and Trotsky's expulsion from the Soviet Union while I was in Germany was still fresh in my mind. What accounted for my failure to discover the truth and even to search for it with the zeal with which I would have pursued reports of gross injustice committed elsewhere? Several things. First, I had come to the Soviet Union with the faith of someone already committed to the Socialist ideal and convinced that the Soviet Union was genuinely dedicated to its realization. This conviction had been nurtured and strengthened by the Soviet Union's peace policy, its enlightened social legislation all along the line, and despite its doctrinal orthodoxy, which I never shared, its declared educational theory and practice."

John Dewey had visited the Soviet Union the previous year. Hook shared his views on the Soviet education system: "My teacher, John Dewey, who had visited Russia in 1928, had declared its educational system to be the most enlightened in the world and closest to his own ideals. Actually, although I was as impressed as Dewey was by the pronouncements of Soviet educators, I was never taken in by the claims that Soviet educational practices lived up to them on a large scale. On the basis of what I was told by the Russian families I got to know, I became convinced that Dewey in 1928 and George Counts, whom I met that summer in 1929, were being shown specially selected classes and schools that were not representative at all. Nonetheless, Dewey's report of the state and, above all, the promise of Soviet culture as a consequence of a revolution... was shared by a host of liberal and radical visitors to the Soviet Union during the twenties."

Political Activist

Sidney Hook was an early member of the Socialist Party of America and a supporter of Norman Thomas. "At the time the Socialists were not short of revolutionary rhetoric, and their chief spokesman, Norman Thomas, towered head and shoulders intellectually above the mediocrities of the rival organization. The real reason was that, in attaching themselves to the organizations influenced by the Communist Party, they felt they were identifying with the Soviet Union - the country that was showing the world the face of the future: a planned society, in which, allegedly, there was no unemployment, no human want in consequence of the production of plenty, and in which, allegedly, the workers of arm and brain controlled their own destinies... The Socialists, it was claimed, lacked the verve and fire required for the total expropriation of the bourgeoisie, for the destruction of its state apparatus, and for the transformation of existing educational, legal, and political institutions from top to bottom."

In the 1932 Presidential Election Hook joined Sherwood Anderson, Louis Fraina, John Dos Passos, Waldo Frank, Langston Hughes, Lincoln Steffens, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, Granville Hicks and Matthew Josephson, in endorsing the American Communist Party. Hook explained in his autobiography: "I had endorsed the Communist Party electoral ticket... In 1932, the depression was close to its nadir. The outlook seemed economically hopeless, and despair pervaded all social circles. Capitalism as a functioning economic system appeared bankrupt. The programs of both the Republican and Democratic parties called for balancing the budget but contained no proposals for major social reforms. The illusion that the Soviet Union had solved the major economic problems flourished, even though it was buttressed by no hard evidence, only remarkable propaganda. To me it seemed overwhelmingly likely that Hitler would soon come to power and carry out the program of war he had frankly outlined in Mein Kampf. The only hope of frustrating his war plans against the Soviet Union was a revolution in Germany that would unite all the opposition forces headed by the working classes.... Our support of the electoral ticket was more symbolic than organizational, an expression of protest, hope and faith nurtured by naivete, ignorance and illusion. At the time I was probably the best known academic personality who had publicly taken this position, although quite a number of other academic figures had declared themselves for Norman Thomas, the American Socialist Party candidate, whose position seemed very little different from that of the Socialist Party in Germany and as ineffectual in preventing the economic debacle there or here."

In March 1933, Hook was asked to meet Earl Browder: "I want to talk with you about some things much more important to our movement... We and what we represent are handicapped by our inability to counteract the capitalist press. It molds public opinion in powerful ways. We think that there is a way of getting our voice heard so that our position on the crucial issues of the day, without being identified as that of the Communist Party, will get a hearing beyond anything possible by means of our own press. We would like you to find plausible occasions to visit the chief metropolitan centers of the country from Boston to San Francisco - it wouldn't be necessary in New York - and help build up circles of sympathizers, individuals not known to be politically active in any of our organizations but friendly to the Soviet Union and therefore to us. They should be primarily professionals and small businessmen and women. When an important problem arises on matters of domestic or foreign policy, on a signal from you or transmitted through a trusted local intermediary whom they know, we would ask them to write letters to the press - national and local - stating in their own way and in their own modes of expression, a position that we believe would further the cause of peace and greater social justice. Properly done, there would be enough variation in these communications to the editors to allay any suspicion of organized action. The cumulative effect of these letters to the press, bearing authentic names from authentic addresses, is sure to have a strong effect on editorial opinion. At the very least they would do something to counterbalance the class bias of the news reports on labor, on what is happening in Germany, and developments in the Soviet Union."

Browder then went on to argue: "I now come to something of vital importance. There is little doubt that Hitler will rearm Germany and, with the help of the Western capitalist powers, unleash war against the Soviet Union. The defense of the Soviet Union is the first and overriding duty of anyone who believes in the cause of socialism. It is the chief bulwark against fascism. You have an opportunity to be of immense service, particularly because of your university connections. We would like you to find opportunity to travel to the major campuses of the country that are centers of scientific and industrial research. It should not be difficult to find and cultivate the acquaintance of at least one trustworthy individual sympathetic to the Soviet Union and its need for defense and survival against the threat of fascism. After his reliability has been established, all he would be asked to do is to report on the work being done, the experiments and projects under consideration, any new inventions or devices particularly of a military and industrial character. Even partial and incomplete information might be of the utmost significance. Most valuable of all would be word about secret research of any character. The reports of your informants would be channeled through you to us. You would not be asking any antifascist to do anything dishonorable, for he would be helping to defend the Soviet Union and the cause of the international working class."

Hook reported later in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "Stripped of its euphemisms, this was a request that I set up a spy apparatus! Before Browder was through outlining the details of this third proposal, I was in a state of panic. At first I thought it was a kind of test of my resoluteness and loyalty, to see how I would react. But why should I be tested? I had not applied for membership in the Communist Party. All the overtures had come from them to me. When Browder finished speaking, I was at first at a loss for words." When Hook pointed out he was not a member of the American Communist Party Browder replied: "I know, but for some kinds of work official membership in the Party is not necessary. Sometimes it is an advantage to be able to say that one is not a member." Hook was later to discover that Browder was himself a Soviet spy and that the main objective was to recruit non-party members to obtain secret information. had a strategy of recruiting spies who were not party members. Hook rejected the offer and cut off all contact with the party.

American Workers Party

Hook was disturbed by the events that were taking place in the Soviet Union. He no longer felt he could support the policies of Joseph Stalin. Hook now decided to join with other like-minded people to form the American Workers Party (AWP). Established in December, 1933, Abraham Muste became the leader of the party and other members included Louis Budenz, James Rorty, V.F. Calverton, George Schuyler, James Burnham, J. B. S. Hardman and Gerry Allard.

Hook later argued: "The American Workers Party (AWP) was organized as an authentic American party rooted in the American revolutionary tradition, prepared to meet the problems created by the breakdown of the capitalist economy, with a plan for a cooperative commonwealth expressed in a native idiom intelligible to blue collar and white collar workers, miners, sharecroppers, and farmers without the nationalist and chauvinist overtones that had accompanied local movements of protest in the past. It was a movement of intellectuals, most of whom had acquired an experience in the labor movement and an allegiance to the cause of labor long before the advent of the Depression."

Soon after its formation of the AWP, leaders of the Communist League of America (CLA), a group that supported the theories of Leon Trotsky, suggested a merger. Sidney Hook, James Burnham and J. B. S. Hardman were on the negotiating committee for the AWP, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern and Arne Swabeck, for the CLA. Hook later recalled: "At our very first meeting, it became clear to us that the Trotskyists could not conceive a situation in which the workers' democratic councils could overrule the Party or indeed one in which there would be plural working class parties. The meeting dissolved in intense disagreement." However, despite this poor beginning, the two groups merged in December 1934.

Show Trials

The Show Trials of 1936 and 1937 shocked and angered Hook. "The Moscow Trials were also a decisive turning point in my own intellectual and political development. I discovered the face of radical evil - as ugly and petrifying as anything the Fascists had revealed up to that time - in the visages of those who were convinced that they were men and women of good will. Although I had been severely critical of the political program of the Soviet Union under Stalin, I never suspected that he and the Soviet regime were prepared to violate every fundamental norm of human decency that had been woven into the texture of civilized life. It taught me that any conception of socialism that rejected the centrality of moral values was only an ideological disguise for totalitarianism. The upshot of the Moscow Trials affected my epistemology, too. I had been prepared to recognize that understanding the past was in part a function of our need to cope with the present and future, that rewriting history was in a sense a method of making it. But the realization that such a view easily led to the denial of objective historical truth, to the cynical view that not only is history written by the survivors but that historical truth is created by the survivors - which made untenable any distinction between historical fiction and truth-led me to rethink some aspects of my objective relativism. Because nothing was absolutely true and no one could know the whole truth about anything, it did not follow that it was impossible to establish any historical truth beyond a reasonable doubt. Were this to be denied, the foundations of law and society would ultimately collapse. Indeed, any statement about anything may have to be modified or withdrawn in the light of additional evidence, but only on the assumption that the additional evidence has not been manufactured."

As Hook explained in Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The charges against the defendants were mind-boggling. They had allegedly plotted and carried out the assassination of Kirov on December 1, 1934, and planned the assassination of Stalin and his leading associates - all under the direct instructions of Trotsky. This, despite their well-known Marxist convictions concerning the untenability of terrorism as an agency of social change. Further, they had conspired with Fascist powers, notably Hitler's Germany and Imperial Japan, to dismember the Soviet Union, in exchange for the material services rendered by the Gestapo. In order to allay the suspicion flowing from the Roman insight that no man suddenly becomes base, the defendants were charged with having been agents of the British military at the very time they or their comrades were storming the bastions of the Winter Palace. In addition, although the indictment seemed almost anticlimactic after the foregoing, they were accused of sabotaging the five-year plans in agriculture and industry by putting nails and glass in butter, inducing erysipelas in pigs, wrecking trains, etc."

Hook went on to argue: "Despite the enormity of these offenses, all the defendants in the dock confessed to them with eagerness and at times went beyond the excoriations of the prosecutor in defaming themselves. This spectacular exercise in self-incrimination, unaccompanied by any expression of defiance or asseveration of basic principles, was unprecedented in the history of any previous Bolshevik political trial. Equally mystifying was the absence of any significant material evidence. Although there were references to several letters of Trotsky, allegedly giving specific instructions to the defendants to carry out their nefarious deeds, none was introduced into evidence. The most substantial piece of evidence was the Honduran passport of an individual who claimed to be an intermediary between Trotsky and the other defendants, which was presumably procured through the good offices of the Gestapo, although it was common knowledge that such passports could be purchased by anyone from Honduran consuls in Europe for a modest sum."

The Dewey Commission

Hook was disturbed by the way liberals reacted to the Moscow Show Trials compared to the way that they behaved in response to events in Nazi Germany. Hook, who had little sympathy for Trotskyists as a group, believing that they "were capable of doing precisely what I suspected the Stalinists of doing - if not on the same scale, at least in the same spirit. It was indeed ironical to find the Trotskyists, victims of the philosophy of dictatorship they had preached for years, blossoming out as partisans of democracy and tolerance." However, Hook believed that Leon Trotsky should be given political asylum in the United States: "The right to asylum was integral to the liberal tradition from the days of antiquity. It was shocking to find erstwhile liberals, still resolutely engaged in defending the right of asylum for victims of Nazi terror, either opposed or indifferent to the rights of asylum for victims of Stalin's terror. Of course more than the right of asylum was involved. There was the question of truth about the Russian Revolution itself."

Hook persuaded Freda Kirchwey, Norman Thomas, Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos, Bertrand Russell, Reinhold Niebuhr, Franz Boas, John Chamberlain, Carlo Tresca, James T. Farrell, Benjamin Stolberg and Suzanne La Follette to join a group that might establish a committee to look into the claims made during the Moscow Show Trials. Hook believed that the best place to hold the investigation was in Mexico City where Trotsky was living in exile and the ideal person to head the commission was his close friend, the philosopher, John Dewey.

As Jay Martin, the author of The Education of John Dewey (2002), has pointed out: "The leaders of the American committee... realized that a tribunal consisting entirely of Trotsky sympathizers could scarcely achieve credibility on the international stage. What they needed was a group, and especially a chairman, who had an international reputation for fairness and whose integrity could be accepted by liberals, Soviet sympathizers, and intellectuals everywhere. Encouraged by the socialist philosopher Sidney Hook, their hopes soon fastened on Hook's dissertation adviser, the seventy-eight-year-old John Dewey, as the best possible choice for chair. After all, Dewey had been celebrated in the Soviet Union when he went there in 1928 and had been asked by the Socialist Party to run on their ticket for governor of New York. But he was quoted every week or so in the moderate New York Times; he was invited to the White House for dinner; he was the friend of powerful capitalists."

Hook was aware that Dewey had been working on Logic: The Theory of Inquiry for the last ten years and was desperate to finish the book. Hook later recalled in his autobiography Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The first and most important step of the commission was to appoint a subcommission to travel to Mexico City to take Leon Trotsky's testimony. It was crucial for the success of the commission that John Dewey consent to go, because without him the press and public would have ignored the sessions. It would be easy for the Kremlin to dismiss the work of the others and circulate the false charge that they were handpicked partisans of Trotsky. Only the presence of someone with Dewey's stature would insure world attention to the proceedings. But would Dewey go? And since he was now crowding seventy-nine, should he go? Dewey must go, and I must see to it."

Dewey was warned by family and friends of the dangers of becoming entangled in "this messy business." However, he eventually agreed to carry out the task. Dewey wrote to a friend: "I have spent my whole life searching for truth. It is disheartening that in our own country some liberals have come to believe that for reasons of expediency our own people should be left in the dark as to the actual atrocities in Russia. But truth is not a bourgeois delusion, it is the mainspring of human progress."

Upon hearing that John Dewey was willing to head the commission Leon Trotsky gave a speech transmitted by telephone to a large audience at the New York Hippodrome, stating: "If this commission decides that I am guilty of the crimes which Stalin imputes to me, I pledge to place myself voluntarily in the hands of the executioner of the G.P.U."

The Dewey Commission conducted thirteen hearings at the home of Diego Rivera in Coyoacan, from 10th April to 17th April, 1937, that looked at the claims against Trotsky and his son, Lev Sedov. The commission was made up of Dewey, Suzanne La Follette, Carlo Tresca, Benjamin Stolberg, Carleton Beals, Otto Ruehle, Alfred Rosmer, Wendelin Thomas, Edward A. Ross and John Chamberlain. Dewey invited the Soviet Union government to send documentary material and legal representatives to cross-examine Trotsky. However, they refused to do that and the offer for the Soviet ambassador to the United States, Andrei Troyanovsky, to attend, was also rejected.

John Dewey opened the hearings with the words: "This commission, like many millions of workers of city and country, of hand and brain, believes that no man should be condemned without a chance to defend himself.... The simple fact that we are here is evidence that conscience demands that Mr. Trotsky be not condemned before he has had full opportunity to present whatever evidence is in his possession in reply to the guilty verdict returned in a court where he was neither present nor represented. If Leon Trotsky is guilty of the acts with which he is charged, no condemnation can be too severe."

Leon Trotsky and Lev Sedov were defended by the lawyer Albert Goldman. In his opening speech he argued: "We are determined to convince the members of this commission, and everyone who reads and thinks with an independent mind, beyond all doubt, that Leon Trotsky and his son are guiltless of the monstrous charges made against them." According to Jay Martin: "The commissioners raised various questions about the charges against Trotsky. He answered vigorously, with a remarkable command of detail and capacity for analysis... Despite his heavy accent, Trotsky spoke with exceptional clarity, sometimes even with wit and beauty, and always with impeccable logic."

The Dewey Commission was attacked by journals under the control of the American Communist Party. Its newspaper, The Daily Worker, attacked Dewey as a "deluded old man" who was being "duped by the enemies of socialism" and was charged with being "an enemy of peace and progress". An editorial in the New Masses mocked "the so-called impartial inquiry". It added that the "hearings merely presented a rosy picture of Trotsky while blackening the Moscow defendants who implicated him." The Soviet Union government issued a statement describing Dewey as "a philosophical lackey of American imperialism".

According to Hook, one of the commission members, Carleton Beals, was under the control of the Soviet Union. During the investigation he resigned: "My resignation went in the next morning. Dewey accused me of prejudging the case. This was false. I was merely passing judgment on the commission. He declared that I had not been inhibited in my questioning. He declared that I had the privilege of bringing in a minority report. My resignation was my minority report. How could I judge the guilt or innocence of Mr. Trotsky, if the commission's investigations were a fraud?"

Beals received considerable media attention when he published an article on the case in the Saturday Evening Post: "I was unable to put my seal of approval on the work of our commission in Mexico. I did not wish my name used merely as a sounding board for the doctrines of Trotsky and his followers. Nor did I care to participate in the work of the larger organization, whose methods were not revealed to me, the personnel of which was still a mystery to me. Doubtless, considerable information will be scraped together. But if the commission in Mexico is an example, the selection of the facts will be biased, and their interpretation will mean nothing if trusted to a purely pro-Trotsky clique."

In the article Beals made no attempt to defend the case made against Trotsky at the Moscow Show Trials. Instead he concentrated on stating his belief that Trotsky had been in contact with the people found guilty and executed in Moscow: " I decided to jump into the arena once more with a line of questioning to show Trotsky's secret relations with the Fourth International, the underground contacts with various groups in Italy, Germany and the Soviet Union. Trotsky, of course, had steadfastly denied having had any contacts whatsoever, save for half a dozen letters, with persons of groups in Russia since about 1930. This was hard to swallow."

Beals also accused Leon Trotsky of having an unreasonable hatred of Joseph Stalin: "His mind is a vast repository of memory and passion, its rapierlike sharpness dulled a trifle now by the alternating years of overweening power and the shattering bitterness of defeat and exile; above all, his mental faculties are blurred by a consuming lust of hate for Stalin, a furious uncontrollable venom which has its counterpart in something bordering on a persecution complex - all who disagree with him are bunched in the simple formula of G.P.U. agents... This is not the first time that the feuds of mighty men have divided and shaken empires, although, possibly, Trotsky shakes the New York intelligentsia far more than he does the Soviet Union."

The Dewey Commission published its findings in the form of a 422-page book entitled Not Guilty. Its conclusions asserted the innocence of all those condemned in the Moscow Trials. In its summary the commission wrote: "We find that Trotsky never instructed any of the accused or witnesses in the Moscow trials to enter into agreements with foreign powers against the Soviet Union. On the contrary, he has always uncompromisingly advocated the defense of the USSR. He has also been a most forthright ideological opponent of the fascism represented by the foreign powers with which he is accused of having conspired. On the basis of all the evidence we find that Trotsky never recommended, plotted, or attempted the restoration of capitalism in the USSR. On the contrary, he has always uncompromisingly opposed the restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union and its existence anywhere else.... We therefore find the Moscow Trials to be frame-ups. We therefore find Trotsky and Sedov not guilty".

Sidney Hook died in Stanford, California, on 12th July, 1989.

Primary Sources

(1) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

The Williamsburg area of Brooklyn, before World War I, was a slum of checkered ethnic pattern - Irish, Italian, German, Jewish, with a scattering of East and Southeastern European families. The ethnic areas were largely enclaves separated from other ethnically related groups. To travel from one Jewish enclave to another, a short mile away, one had to go through an Italian enclave or an Irish one, depending on the direction. Public School 145 was in an Irish-German district, and those of us who lived on Bushwick Avenue above Flushing or below Myrtle not infrequently had to fight our way through. Going to school was not very hazardous, because we could time ourselves to arrive early, just after the Irish and German boys left their neighborhoods. Returning was more difficult, because the little toughs to whom we were outsiders - "Sheenies" they called us - would hurry home to prepare for us, with snowballs in winter and rocks at other times. We often outmaneuvered them by taking circuitous routes home or by traveling in packs ourselves...

The physical conditions under which we lived were quite primitive. On Locust Street where we lived for some years, the toilets were in the yard. In other tenements they were shared with another family. All were railroad flats, heated only by a coal stove and boiler in the kitchen. Gas provided illumination and the most common means of suicide. We froze in winter and fried in summer. Vermin were almost always a problem, and the smell of kerosene pervaded our bedrooms, which had no windows and gave on skylights instead. The public baths were used until bathtubs were installed. The women worked like pack horses; their work was never done. Nor could their husbands have shared their household labors. My father left for work before we arose; he returned from work when we were ready to go to bed. More than once, to the astonishment and amusement of the children, he would fall asleep at the dinner table with the soup spoon in his hand poised in the air.

Success meant quick flight from Williamsburg to Brownsville or Flatbush or other areas. Although Williamsburg here and there still boasted of old private homes and some open fields, it was a community of shared poverty. I have never seen or read of any other slum in New York that was worse during those years.

Strangely enough, despite all this, we were not unhappy as children. We did not know what we were missing, and the warmth of the family tie largely made up for what we may have suspected was missing. Amidst the noise and the filth, there was a sense of privacy and self-respect and the hush and color of the Sabbath tradition. Above all there was a feeling of hope. The hope was sustained by a faith that the doors of opportunity would be opened by education. No generation of parents has ever been prepared to sacrifice so much for the education of their children. That hope suffered a quiet death whenever a child had to drop out of school to add his mite of earnings to the family income. There was also hope in America, nurtured, despite the incidents of religious hostility and discrimination outside the enclave walls, by the public school. Very few of us, even when we found the school boring, ever got to know the truant officer.

Although the public schools were religiously attended (children feared the wrath of their parents much more than the threats of the truant officer), the classroom experience was far from enjoyable. First of all, the discipline was exacting. Our teachers were little more than martinets. We had to sit erect, with our hands clasped on the edge of the desks or folded behind our back, in absolute silence. Everything was done at command, according to a rigorous and rigid schedule. Even the occasional interesting lesson would be broken off when the allotted time was up, no matter how eager the students were to continue. The slightest infraction of proper conduct -a whisper, a paper dropped on the floor, a shove, a pinch, or the dipping of a girl's braid in the open inkwell-evoked withering sarcasm, denigrating scolding, and corporal punishment-whacks with the twelve-inch ruler on open extended palms, and whacks with the heavy ferule on the rump. Only the boys got the latter treatment, which was more humiliating than painful. In addition there was staying in after school was over and writing a hundred times some silly sentence like "I must not talk to my neighbor." Conversely, the "good" students were relentlessly held up to the rest as a model by insensitive teachers, unaware of how hateful "teacher's pets" were to other children. This happened to me all too often.

To most of us the boredom was worse than the discipline. The dreary drill seemed directed to the dullest in the class. Woe to us if we were caught reading anything concealed in our official readers. We were not challenged enough and were often rebuked for raising our hands to answer questions before they were asked. Whatever the causes of the varying interests and learning capacities of the children, it never seemed to me when I was a student (or when I became a teacher in the public schools in the early twenties) that anything was gained by mixing students of widely different abilities in the same conventional classroom. The bright were bored stiff, and the dull ones could not help feeling more stupid in the presence of quick and eager learners. And it seemed to me the bright students suffered more than the dull. Oddly enough, however, they earned the respect of the dull-witted bullies, not only because they occasionally did the bullies' homework, but because of the apparent natural appreciation of one kind of "elite" for another. So little was there to relieve the intellectual boredom -ocasionally a spelling bee or an improvised story - that I would often go to bed praying that the school would burn down before morning. Life in the classroom-perhaps it would be more accurate to say the absence of life-accounted for it.

(2) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

I entered Boys High School, Brooklyn, in February 1916. At that time it was renowned for its rigorous scholastic standards and enjoyed the same reputation among secondary schools as City College did among institutions of higher learning. It was a good forty-five minute walk from the Williamsburg slum in which we lived. Although there were two high schools closer by, I preferred to go to Boys because it was considered the superior school.

Europe was at war. The news of the war and the ominous threats of American involvement dominated the headlines. It created an atmosphere that pervaded everyday life, partly because of the family ties of so many recent immigrants from Europe, but mainly because they feared that the United States would be caught up in the bloody maelstrom. The sentiment of the local population was not so much pro-German as anti-Russian. They still had vivid recollections of the pogroms that were tolerated by the tsarist regime, and of the Mendel Beilis trial in Russia, involving fantastic charges of the ritual murder of Christian children. These events contrasted with their memory of the relative tolerance of minority cultures and religions in Germany and especially Austria, whose aging Emperor Franz Josef was often referred to as a protector of the Jews.

The curriculum of Boys High School was still fairly classical in those days. Latin was a required subject for two or three years, as were algebra, geometry, a year of biology, a year of physics or chemistry, a modern foreign language, three years of European and American history, and four years of English. Some stress was placed on elocution in the English classes. Compared to contemporary high schools, it would be considered an elite school. Some of its distinguished graduates, Clifton Fadiman for one, have written about their educational experience as if it were ideal and contrasted its course of study very favorably with the curricula that were introduced later. The truth of the matter-and I sat in some of the very classes that Fadiman has described in such glowing terms - is that no one learned anything in that school who was not already self-motivated, and not (with the rarest of exceptions) by virtue of the teaching but despite it. The pedagogy was execrable. The textbook was the only authority, and except in some classes where problems were studied (mathematics and physics), excellence in scholarship depended upon the students' ability to regurgitate it. The all-male teaching faculty, for the most part, knew little about methods of teaching, brooked no contradiction from students, and were even impatient of questions.

Instruction was not geared to broadening the interests and liberalizing the minds of the students but to the passing of examinations, especially the Regents' tests. I do not recall a single class that ended on a problem whose resolution we were moved, or ever urged, to think about. The teaching was not only authoritarian but conducted in a spirit of hostility, aimed at detecting an unprepared student and correcting him if he was out of line with respect to even trivial details. The result was that for many students, among them the best, outwitting the teacher became more challenging than mastering the lesson.

My friends and I made a point of coming to class unprepared and resorted to all sorts of stratagems, including the sharing of scraps of information we picked up to good purpose on our walks to school. I smile when I recall the silly things we did to avoid boredom or provoke teachers who seemed devoid of any sense of humor or genuine interest in us.

(3) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

The first doubts began to emerge only after the Russian October Revolution, when the voices of Menshevik and Anarchist protest reached us, but only faintly. These voices and our doubts were drowned out by the thunder of the counterrevolutionary armies of Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, and the remarkable propaganda of the Bolsheviks, whose mastery of all the media of modern communication has remained unsurpassed from that day to this.

It should not be hard for the reader to reconstruct the mood of those of us who had become infected with the Socialist ideal. It was a source of hope in a world of deprivation-perhaps I should say of chronic need since we did not feel deprived, accustomed as we were to its lacks and indignities. The Socialist ideal served as a never-failing consolation when things went wrong or grim news of disaster or failure reached us. Living in the dark shadows of the European war, with the daily headlines about bloody battles shouted in our ears morning and evening, the Socialist appeal to reason and pleas for peace gave us a feeling that we were part of a movement of the elect, seeking to save civilization in a world of chaos. In short, our socialism was an ersatz religion in that we lived in its light, were buoyed up by its promise, and prepared to make sacrifices for it...

There was one other feature of our Socialist allegiance. We never thought of it or ourselves as non-American or anti-American. On the contrary. We sought continuities with the American revolutionary past. Most of us were native-born of immigrant parents. We were at home in American history. Our heroes were Tom Paine, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and the abolitionists. The unionist wisdom of Lincoln escaped us. Looking back, one pathetic oversight is apparent. We were completely oblivious to the fact that New York was not America. We did not know what most of the country thought and still less how it felt. We lived in the world of our ideas and imagination, even though the newspapers were full of stories about lynching bees elsewhere, and even though some of us knew of racial disturbances in Brooklyn. Had we been sent out of New York and dispersed into other areas of the country, we would undoubtedly have perceived the irrelevance of our grandiose ideas at a time when the American working class was not even properly organized in a trade-union movement.

Many hypotheses have been advanced to account for the fact that the Socialist movement or Socialist ideas never took root in America. Whatever the reason, it is not the case that the language we spoke was foreign in its style or diction. To sense the authenticity of the American idiom, all one need do is read Daniel DeLeon's pamphlets, in which Socialist ideas were couched in apposite references to the American folk humorists. Later, of course, when the Socialist movement was split by the Communists, the picture changed. As self-declared partisans of the Soviet Union, dedicated primarily to its defense, the Communists seized the limelight of public consciousness. It was not long before the "foreignness" of Socialist ideas -as the Communists represented them-to the traditions of indigenous American radicalism seemed at first plausible and then overwhelmingly evident, but at the time of which I write, the failure of the Socialist idea to take root seems best explained by the many opportunities for social and personal advancement that, although limited, still abounded in America. The frontier lands were gone, but there remained other economic areas in which, with effort and luck, impoverished newcomers could create for themselves, and especially for their children, a tolerable life. The Socialist ideal failed to take root even in the thirties when so many were hurled into the pits of poverty; even when the state stepped in to initiate a program of remedial measures that had been urged in Socialist platforms of the past. (Indeed, the state did more than that. It helped organize the trade-union movement and made collective bargaining the law of the land.)

Since we were not anarchists, on what grounds then could we regard the state as necessarily evil? We saw the problem as one of an enlightened state furthering the common welfare, as we defined it, versus an oppressive state furthering the interests of a privileged group. We were not self-righteous, but like Socialists everywhere, our motives were patently good in our own eyes. Since we pictured ourselves or others like us as the governing elite of the future, we regarded it as absurd that our control of the state, won through the democratic process, could constitute a threat to freedom.

I recall that before the American Socialist movement became convulsed by strife over the attempt to bolshevize it, one of the issues that divided its adherents was whether compensation should be paid to the owners of industries that were to be socialized. Some were for outright expropriation, others for strictly legal and constitutional procedures. Neither side noticed that, in consequence of the Prohibition amendment, a billion-dollar industry was expropriated overnight without compensation.

The greatest disillusionment of my youthful Socialist years was the discovery that the man from whose son I had imbued my first knowledge and enthusiasm about socialism betrayed its ideals and repudiated them with scorn. He had been a skilled worker in the metal trades. The war gave him an opportunity to open his own shop, and war contracts made him very wealthy. My first shock was to learn that he had hired gangsters to prevent his shop from being organized; my second was to find his son attempting to hire strike breakers among the older brothers of his friends. By that time he was scoffing at my Socialist beliefs. Subsequent developments were like an old-fashioned melodrama. The father became very rich, changed his name, left his family, divorced his old-fashioned wife, and flaunted a succession of mistresses. His older son, whom he had made a partner in an earlier crooked deal to circumvent a business associate, then legally maneuvered him out of the company, and cut off his funds. Before long he was abandoned by everyone except his many creditors, took to drink, was turned out of his hotel, and ended up on Skid Row when his wife and sons refused to take him back.

My own friend, his son, became a partner in the flourishing business and remained firm in his anti-Socialist convictions. I soon lost touch with him. About sixteen years later he showed up at a meeting of the American Workers Party, at which I was the chief speaker. He had seen the announcement in the newspaper, he said, and had come "to see whether you still believed that old stuff."

Although most of my life I have heard it said that people become Socialists out of envy of the rich, my friend and his father are the only ones I ever met for whom this was true. I have met a few wealthy persons, almost always of inherited wealth, who out of guilt became Socialists and even Communists. There is plenty of evidence that this is not an uncommon phenomenon, especially when the sense of guilt is felt by those who lack political knowledge and intellectual sophistication.

My experience has been, with the sole exception just noted, that Socialists do not envy the rich. Nor in my experience do the poor envy the rich as much as the rich envy those who are richer than themselves.

(4) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

Professor Harry Overstreet, chairman of the Department of Philosophy... had been converted to John Dewey's conception of philosophy, but unfortunately he did not hold up his end of the technical arguments when challenged by philosophy students whose dialectical razors had been honed in the classes of Morris Cohen. Nor was he highly regarded by fanatical young Socialists, to whom he was a mere social reformer whose ineffectual programs made more difficult the radicalization of the working class. The virtuous barbarism of the latter group and the intellectual arrogance of the former prevented them from properly appreciating and profiting from his instruction.

Harry Overstreet was a man of an extraordinarily sweet and generous disposition. He had genuine dramatic talent that enabled him to personalize the situations and problems out of which the conflict of human values developed. During his sabbatical year, he had worked anonymously as an unskilled laborer in a Midwest factory and was one of the first persons who tried to come to grips with a problem that only decades later became central in discussions of social philosophy. This was the nature of "work" in any industrial society and the difficulties of achieving self-fulfillment in tending the assembly lines of mass production. Unfortunately he could not do justice to his own insights, but instead entertained us with autobiographical tidbits and vivid accounts of his own family life and the difficulties of growing up.

Or he would regale the class with readings from H. L. Mencken. Those who took his courses to complete a requirement didn't mind, but there was not enough substance in them to challenge the serious students of philosophy.

On occasion, however, Overstreet would flare up with an eloquent outburst of denunciation at some particularly outrageous act of oppression. This was especially hazardous during the days of the Palmer raids and subsequent deportations. There were few organized protests against these brutal highhanded measures that crassly violated the key provisions of the Bill of Rights.

(5) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

The general public reacted to the excesses as if they were a passing heat wave. In the postwar hysteria of the time, it seemed as if the public either supported these measures or, more likely, was indifferent to them. One case that moved me profoundly was that of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

Goldman and Berkman had been unjustly convicted on the flimsiest evidence of conspiring to prevent young men from registering for the draft. What they had done was merely to express their opposition to conscription, which they had every right to do. After a caricature of a trial, they were sentenced to two years in jail, heavily fined, and ordered deported to Russia, from which they had emigrated as children, at the expiration of their sentence. The case against these truly noble idealists, whose chief failing was an incurable naivete, should have been thrown out of court.

The day the S.S. Buford sailed with them and 239 others on board was one of the darkest days of my life. Several days after the Buford left port, Professor Overstreet, in a large lecture section, made an impassioned reference to the Buford as "the Ark of Liberty" on the high seas. A hush fell over the class. Suddenly a student known to us for his right wing sentiments rushed from the room. In the atmosphere of the moment, we were convinced that he was reporting Overstreet's subversive utterance to someone in authority-although for all we really knew, he was merely responding to an exigent call of nature.

(6) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

One of the great teachers of the first third of our century was Morris R. Cohen of the College of the City of New York, where he taught courses in philosophy from 1912 to 1938. By conventional pedagogical standards, he would not be considered a great or even a good teacher, for he inspired only a few of his students to undertake careers in philosophy and overawed the rest. Nonetheless his prowess as a teacher became legendary and his ideas a force in the intellectual community. Yet his classroom techniques would never have won him tenure in any public school system, and he himself confessed he was a failure in his early efforts as an elementary and secondary schoolteacher, because he could not even control his classes. When he first began teaching philosophy at the college level, his manner, he says, was that of a "petty drillmaster." This proved so unsatisfactory that, lacking "verbal fluency," he adopted the Socratic method....

The crude use of the Socratic method is for shock effect. During the years I studied with Morris Cohen, he used it with devastating results in the classroom. If a problem was being considered, Cohen would deny it was a genuine problem. When he restated the problem, every answer to it was rejected as vague or confused or ill informed if not contrary to fact, or as leading to absurd consequences when it was not viciously circular, question-begging, or downright self-contradictory. The students' answers, to be sure, were almost always what Cohen said they were while he dispatched them with a rapier or sledgehammer-and usually with a wit that delighted those who were not being impaled or crushed at the moment. Cohen enjoyed all this immensely, too. There was no animus in this ruthless abortion of error, of stereotyped responses, and of the cliches and bromides that untutored minds brought to the perennial problems of philosophy, and although the students soon felt that whatever they said would be rejected, they consoled themselves with the awareness that almost everyone was in the same boat. When they were not bleeding, they enjoyed watching others bleed. Occasionally Cohen would let up on a student who had the guts and gumption to answer back. If, ignoring the laughter of his fellows, he insisted on his point in the face of Cohen's mounting impatience, that student was subsequently treated more gingerly. Or when Cohen had the answer to a moot point-an answer he was holding in reserve to trot out after he had gone through the class, beheading one student response after another-he would occasionally skip the student who he suspected might supply the answer. Some of us who felt the call of philosophy and had avidly read Cohen's published articles could sometimes anticipate what he had in mind. He let us alone in class, but we had our egos properly pinched in private sessions with him.