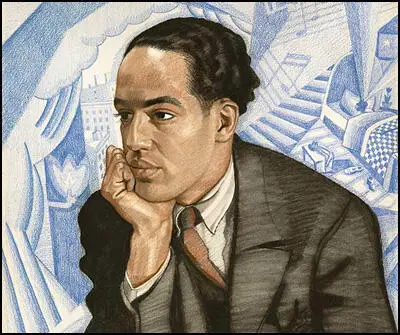

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, on 1st February, 1902. His father deserted the family and Hughes was mainly brought up by his grandmother, whose husband had been killed during the insurrection at Harper's Ferry. His grandmother taught him about Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth and at an early age he was introduced to the writings of William Du Bois. Hughes was also taken to hear Booker T. Washington speak at a public meeting.

Hughes became interested in poetry and was especially influenced by the work of Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman. In 1921 his poem, Speaks of Rivers, was published in Crisis, the journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

He attended Columbia University (1921-22) before working as a steward on a ship bound for Africa. Later he travelled through Italy, Holland, Spain and France before returning to New York City where he published two volumes of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926) and Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927). He also had a essay, The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain, published in The Nation. The work was well-received and helped him win a scholarship to Lincoln University, Pennsylvania.

Hughes published a novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), a collection of short-stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934) and a play, The Mulatto (1935). Much of his work dealt with the effects of the Depression on the American people. Hughes also wrote for the Marxist journal, the New Masses and in 1937 reported on the Spanish Civil War.

Hughes visited the Soviet Union and on his return published A Negro Looks at Soviet Central Asia (1934), where he praised the country's treatment of racial minorities. He had several friends in the American Communist Party but this came to an end with the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

In 1948 he publicly endorsed Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace for president and the following year he condemned the prosecution of Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green under the Alien Registration Act.

A victim of McCarthyism, in March, 1953 Hughes was forced to appear before the House of Un-American Activities. Hughes refused to name the names of other radicals and denied he had ever been a member of the American Communist Party. However, in the months following the hearings, William Du Bois criticised Hughes for failing to defend the victimization of Paul Robeson. Later, he declared his radicalism an error of his youth.

Hughes published several volumes of poetry including: Shakespeare in Harlem (1942), Fields of Wonder (1947), Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) and Ask Your Mama (1961). He also published two autobiographies: The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder as I Wander (1956).

Langston Hughes died on 22nd May, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Langston Hughes wrote about his childhood in his autobiography, The Big Sea (1940)

You see, unfortunately, I am not black. There are lots of different kinds of blood in our family. But here in the United States, the word "Negro" is used to mean anyone who has any Negro blood at all in his veins. In Africa, the word is more pure. It means all Negro, therefore black. I am brown. My father was a darker brown. My mother an olive-yellow. On my father's side, the white blood in his family came from a Jewish slave trader in Kentucky, Silas Cushenberry, of Clark County, who was his mother's father; and Sam Clay, a distiller of Scotch descent, living in Henry County, who was his father's father. So on my father's side both male great-grandparents were white, and Sam Clay was said to be a relative of the great statesman, Henry Clay, his contemporary.

I was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, but I grew up mostly in Lawrence, Kansas. My grandmother raised me until I was 12 years old. Sometimes I was with my mother, but not often. My father and mother were separated. And my mother, who worked, always travelled about a great deal, looking for a better job. When I first started to school, I was with my mother a while in Topeka. She was a stenographer for a colored lawyer in Topeka, named Mr Guy. She rented a room near his office, downtown. So I went to a "white" school in the downtown district.

At first, they did not want to admit me to the school, because there were no other colored families living in that neighbourhood. They wanted to send me to the colored school, blocks away down across the railroad tracks. But my mother, who was always ready to do battle for the rights of a free people, went directly to the school board, and finally got me into the Hamson Street School - where all the teachers were nice to me, except one who sometimes used to make remarks about my being colored. And after such remarks, occasionally the kids would grab stones and tin cans out of the alley and chase me home.

But there was one little white boy who would always take up for me. Sometimes others of my classmates would, as well. So I learned early not to hate all white people. And ever since, it has seemed to me that most people are generally good, in every race and in every country where I have been.

(2) Langston Hughes, The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain (1926)

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual, dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on the top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

(3) Frederick Lutz, member of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in Spain, letter (29th June, 1938)

Heard Langston Hughes last night; he spoke at one of our nearby units - the Autoparque, which means the place where our Brigade trucks and cars are kept and repaired. It was a most astonishing meeting; he read a number of his poems; explained what he had in mind when he wrote each particular poem and asked for criticism. I thought to myself before the thing started "Good God how will anything like poetry go off with these hard-boiled chauffeurs and mechanics, and what sort of criticism can they offer?" Well it astonished me as I said. The most remarkable speeches on the subject of poetry were made by the comrades. And some said that they had never liked poetry before and had scorned the people who read it and wrote it but they had been moved by Hughes's reading. There was talk of "Love" and "Hate" and "Tears"; everyone was deeply affected and seemed to bare his heart at the meeting, and the most reticent (not including me) spoke of their innermost feelings. I suppose it was because the life of a soldier in wartime is so unnatural and emotionally starved that they were moved the way they were.

(4) Langston Hughes, Let America Be America Again (1938)

O, let my land be a land where Liberty,

Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath,

But opportunity is real, and life is free,

Equality is in the air we breathe.

(There's never been equality for me,

Nore freedom in this "homeland of the free.")

(5) Agnes Smedley, letter to Aino Taylor (26th July, 1943)

Langston Hughes, the Negro poet and playwright, is here also. I have known him for many years, having met him once in Russia and once in China. One of his "processional" dramas was produced in Madison Square Garden this past winter with a cast of 250 people. It was a pageant of the Negro race, with white much mixed up in it of course; it was a combination of singing, acting, and dancing. With all his talent, Hughes is the most American creature I've ever met. He's bedrock practical, yet you feel in him that horizonless being that absorbs and considers all things. I feel hidebound compared with him. Only certain things penetrate my hard soul. I have standards and principles and prejudices and weaknesses. Hughes looks on and listens and absorbs everything - that makes him an artist.

(6) Langston Hughes, Dinner Guest: Me (1951)

I know I am

The Negro Problem

Being wined and dined,

Answering the usual questions

That come to white mind

Which seeks demurely

To Probe in polite way

The why and wherewithal

Of darkness U.S.A.--

Wondering how things got this way

In current democratic night,

Murmuring gently

Over fraises du bois,

"I'm so ashamed of being white."

The lobster is delicious,

The wine divine,

And center of attention

At the damask table, mine.

To be a Problem on

Park Avenue at eight

Is not so bad.

Solutions to the Problem,

Of course, wait.

(7) Langston Hughes, Dreams Deferred (1951)

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore--

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over--

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?