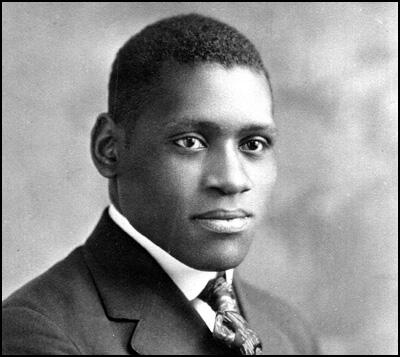

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson, the son of William Drew Robeson, a former slave, was born in Princeton, New Jersey on 9th April, 1898. Paul's mother, Maria Louisa Bustin, came from a family that had been involved in the campaign for African-American Civil Rights.

William Drew Robeson was pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church for over twenty years. He lost his post in 1901 after complaints were made about his "speeches against social injustice". Three years later Paul's mother died when a coal from the stove fell on her long-skirted dress and was fatally burned.

Paul's father did not find another post until 1910 when he became pastor of the St. Thomas A.M.E. Zion Church in the town of Somerville, New Jersey. Paul was a good student but was expected to do part-time work to help the family finances. At twelve Paul worked as a kitchen boy and later was employed in local brickyards and shipyards.

In 1915 Paul Robeson won a four-year scholarship to Rutgers University. Blessed with a great voice, Robeson was a member of the university's debating team and won the oratorical prize four years in succession. He also earned extra money my singing in local clubs.

Paul Robeson, was a large man (six feet tall and 190 pounds) and excelled in virtually every sport he played (baseball, basketball, athletics, tennis). In 1917 Robeson became the first student from Rutgers University to be chosen as a member of the All-American football team. However, in some games Robeson was dropped because the opponents refused to play against teams that included black players.

In 1920 Robeson joined the Amateur Players, a group of Afro-American students who wanted to produce plays on racial issues. Robeson was given the lead in Simon the Cyrenian, the story of the black man who was Jesus's cross-bearer. He was a great success in the part and as a result was offered the leading role in the play Taboo. The critics disliked the play but Robeson got good reviews for his performance.

In 1921 Paul Robeson married Eslanda Goode, a histological chemist at the Presbyterian Hospital in New York. They were soon parted when Robeson went to England to appear in the London production of Taboo, whereas Goode took up her post as the first African American analytical chemist at Columbia Medical Centre.

When Paul Robeson arrived back in the United States he returned to his studies and completed his law degree in February 1923. Soon afterwards he joined the Stotesbury and Milner law office in New York. The only African American in the company, Robeson was the victim of abuse from other members of staff. On one occasion, a stenographer refused to work with him saying "I never take dictation from a nigger". Robeson, who had recently joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), had a meeting with Louis William Stotesbury about this incident. Stotesbury sympathized with Robeson but told him that his prospects for a career in law were limited, as the company's wealthy white clients would be unlikely ever to agree to let him try a case before a judge, as they would fear it would hurt their case.

Paul Robeson decided to leave the legal profession and return to the theatre. He joined the Provincetown Theatre Group and after meeting Eugene O'Neill agreed to play in his play All God's Chillun Got Wings. News of the proposed production reached the press and the American Magazine, a journal owned by William Randolph Hearst, called for the play not to be shown. It especially objected to a scene where a white actress kissed Robeson's hand. Another scene that showed black and white children playing together also caused controversy.

The production went ahead and Robeson received tremendous reviews for his performance. George J. Nathan in the American Mercury wrote that Robeson "with relatively little experience and with no training to speak of, is one of the most thoroughly eloquent, impressive, and convincing actors that I have looked at and listened to in almost twenty years of professional theatre." The play eventually closed in October 1924 after a hundred performances.

Paul Robeson became increasingly concerned with the issue of civil rights. Two of his closest friends were Walter F. White and James Weldon Johnson, two leading figures in the NAACP. Interviewed by the New York Herald Tribune Robeson claimed that "if I do become a first-rate actor, it will do more toward giving people a slant on the so-called Negro problem than any amount of propaganda and argument.

In 1925 Robeson went to London to appear in Emperor Jones. In England he became close friends with Emma Goldman, an anarchist who had been deported from the United States after the First World War. In a letter Goldman wrote to Alexander Berkman, she said: "The more I know the man the greater and finer I find him". In another letter to Berkman she wrote about his "fine character, his understanding and his large outlook on life." She added: "I know few of our American friends among whites quite as humane and large as Paul." While in London he also met other radicals including Max Eastman, Claude McKay and Gertrude Stein.

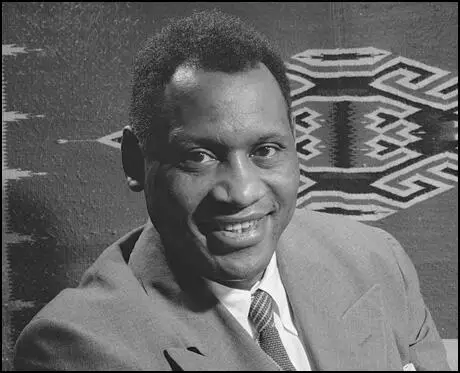

Paul Robeson

On his return to the United States Robeson appeared in Black Boy and in January 1927 began a singing tour of Kansas and Ohio. This was followed by a concert tour of Europe and on his return took the role of Crown in the play Porgy, on Broadway in March 1928. This was followed by Show Boat in London where he performed Ole Man River. One critic, James Agate, of the Sunday Times, suggested that the producers cut a half-hour of the show and fill it with Robeson singing spirituals.

Following his success in Show Boat Robeson went on a concert tour of Europe. This included performances in Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. On his return to London he began a campaign against racial discrimination after he was refused service at the Savoy Grill. The issue was raised with Ramsay MacDonald, the British prime minister, who although condemned the behaviour of the restaurant he claimed "I cannot think of any way in which the Government can intervene." It was later discovered that the Savoy Grill had refused to serve Robeson after complaints had been made about his presence by white American tourists staying in London.

In 1930 Paul Robeson appeared in Emperor Jones in Germany before taking the leading role in Othello in London. The play received a great deal of publicity as it included a scene where Robeson kisses a white actress, Peggy Ashcroft, who played the role of Desdemona. Despite the controversy he show was a great success and ran for 295 performances.

Paul Robeson also appeared in several films including The Emperor Jones (1933) and Sanders of the River (1935). Robeson was upset with the producers of Sanders of the River as he claimed that they had turned it into a pro-imperialist film. He later wrote that "it is the only one of my films that can be shown in Italy and Germany, for it shows the Negro as Fascist States desire him - savage and childish."

In 1935 Robeson and his wife Eslanda Goode, visited the Soviet Union. While there he met William Patterson, one of the leaders of the American Communist Party who was staying in Moscow at the time. They also met two of Eslanda's brothers, John and Frank Goode, who had decided they wanted to live in a socialist country.

Paul Robeson and his wife were impressed with life in the Soviet Union. They liked the improved status of women and the quality of care in the hospitals. Most of all they approved of the way that the minorities were treated in the country. He later wrote that in the Soviet Union he had felt "like a human being for the first time since I grew up. Here I am not a Negro but a human being. Before I came I could hardly believe that such a thing could be. Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity."

On his return to the United States Robeson went to Hollywood to make a movie of Show Boat (1936). He followed this with the films: Jericho (1937), Song of Freedom (1937), Big Fella (1937) and King Solomon's Mines (1937).

Robeson was a strong supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain. On 24th June, 1937, Robeson spoke at a mass rally at the Albert Hall in London in aid of those fighting against General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist Army. In December 1937 he joined Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison, Ellen Wilkinson and other Labour Party leaders in speaking at another rally at the Albert Hall to attack the British government's Non-Intervention Agreement.

In January 1938 Robeson, Eslanda Goode and Charlotte Haldane visited the International Brigades fighting in Spain. While there he heard about Oliver Law of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion who had been killed at Brunete in July 1937. During the offensive Law became the first African-American officer in history to lead an integrated military force. Robeson decided to make a film about Law and "all of the American Negro comrades who have come to fight and die for Spain." Over the next few years Robeson tried several times to raise the money to make the film. He later complained that "the same money interests that block every effort to help Spain, control the Motion Picture industry, and so refuse to allow such a story."

On his return to London he joined the left-wing Unity Theatre and appeared in Ben Bengal's play, Plant in the Sun, a story about white and black workers who combine forces during a strike. He also appeared in a play about Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the Haitian revolution, with C. L. R. James at the Westminster Theatre.

Paul Robeson continued to be active in various political campaigns including the Spanish Aid Committee, Food for Republican Spain Campaign, National Unemployed Workers' Movement and the League for the Boycott of Aggressor Nations. On 27th June 1938, Robeson joined Stafford Cripps, Harold Laski and Ellen Wilkinson, at a rally at Kingsway Hall in favour of Indian Independence Movement.

A strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and his fascist government in Nazi Germany, Robeson was active in the League for the Boycott of Aggressor Nations. He joined the attacks on Neville Chamberlain and his Appeasement Policy but defended Joseph Stalin in his decision to sign the Nazi-Soviet Pact. This resulted in Robeson being attacked by other figures on the left such as Claude McKay who saw Stalin as an unprincipled dictator.

In 1941 Robeson joined Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Vito Marcantonio in the campaign to free Earl Browder, the leader of the American Communist Party, who had been sentenced to four years imprisonment for violating passport regulations.

At the beginning of the Second World War Robeson argued for the United States not to become involved in the conflict. His views changed after the German Army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. He now favoured United States intervention and a creation of a second front in Europe.

Paul Robeson also became an active member of Russian War Relief and along with Fiorello LaGuardia, Harry Hopkins and William Green at a rally on the subject at Madison Square Garden on 22nd July 1942. Robeson argued that the war offered the opportunity to bring an end to oppression and racial prejudice all over the world. At one rally in October 1943 he stated that "this is not a war for the liberation of Europeans and European nations, but a war for the liberation of all peoples, all races, all colours oppressed anywhere in the world."

Robeson continued to make films during the war. This included The Proud Valley (1940), in which he played a heroic miner in Wales and Tales of Manhattan (1942). Robeson was also involved in Native Land (1942), a film directed by Paul Strand. Robeson provided the narration and Marc Blitzstein the music.

In 1946 Robeson led a delegation of the American Crusade to End Lynching to see Harry S. Truman to demand that he sponsor anti-lynching legislation. He also became involved in the campaign to persuade African Americans to refuse the draft.

Robeson's political activities led to him being investigated by House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). On one occasion, when Richard Nixon, a member of the HUAC, asked the actor Adolphe Menjou, how the government could identify Communists, he replied, anyone who attended Robeson's concerts or who purchased his records.

Paul Robeson

The government decided that Robeson and his wife, Eslanda Goode, were members of the American Communist Party. Under the terms of the Internal Security Act, members of the party could not use their passports. Blacklisted at home and unable to travel abroad, Robeson's income dropped from $104,000 in 1947 to $2,000 in 1950.

Paul Robeson finally agreed to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955. He denied being a member of the American Communist Party but praised its policy of being in favour of racial equality. One Congressman, Gordon Scherer of Ohio, commented that if he had felt so free in the Soviet Union why he had not stayed there. Robeson replied: "Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part just like you."

In 1958 the government lifted the ban it had imposed prohibiting Paul Robeson from leaving the United States. After obtaining his passport, Robeson moved to Europe where he lived for five years. He spent his time writing, travelling and giving public lectures. Paul Robeson, whose autobiography, Here I Stand, was published in 1958, died in Philadelphia on 23rd January, 1976.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1931 Eslanda Goode wrote down some thoughts on her relationship with Paul Robeson.

His education was literary, classical, mine was entirely scientific; his temperament was artistic, mine strictly practical; he is vague, I am definite; he is social, casual, I am not; he is leisurely, lazy, I am quick and energetic. He is genial, easily imposed upon, mildly interested in everybody and very impractical; I am pleasant to a few people, affectionately and deeply devoted to a very few, and entirely unaware that anybody else existed. Paul could be rude or say no to anyone; I could relish being rude to anyone who deserved it. He likes late hours, I am an early bird; he likes irregular meals, they are the bane of my life; he likes leaving things to chance, I like making everything as certain as possible; he is not ambitious, although once having undertaken a thing he is never content until he accomplishes it as perfectly as possible; I am essentially and aggressively ambitious, I like to undertake things.

(2) Paul Robeson, letter in the Manchester Guardian (23rd October 1929)

I thought that there was little prejudice against blacks in London or none but an experience my wife and I had recently has made me change my mind and to wonder, unhappily, whether or not things may become almost as bad for us here as they are in America.

A few days ago a friend of mine invited my wife and myself to the Savoy grill room at midnight for a drink and a chat. On arriving the waiter, who knows me, informed me that he was sorry he could not allow me to enter the dining room. I was astonished and asked him why. I thought there must be some mistake. Both my wife and I had dined at the Savoy and in the grill room many times as guests.

I sent for the manager, who came and informed me that I could not enter the grill room because I was a negro, and the management did not permit negroes to enter the rooms any longer.

(3) Paul Robeson was interviewed by R. E. Knowles in the Toronto Daily Star (21st November 1929).

The African people have an almost instinctive flair for music. This faculty was born in sorrow. I think that slavery, its anguish and separation - and all the longings it brought - gave it birth. The nearest to it is to be found in Russia, and you know about their serf sorrows. The Russian has the same rhythmic quality - but not the melodic beauty of the African. It is an emotional product, developed, I think, through suffering.

(4) Paul Robeson, speech about the Spanish Civil War at the Albert Hall, London, on 24th June 1937.

Like every true artist, I have longed to see my talent contributing in an unmistakably clear manner to the cause of humanity. I feel that tonight I am doing so. Every artist, every scientist, every writer must decide now where he stands. He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights. There are no impartial observers. The battle front is everywhere. There is no sheltered rear. The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative. The history of this era is characterized by the degradation of my people. Despoiled of their lands, their culture destroyed, they are in every country save one (the USSR), denied equal protection of the law, and deprived of their rightful place in the respect of their fellows. Not through blind faith or coercion, but conscious of my course, I take my place with you. I stand with you in unalterable support of the government of Spain, duly and regularly chosen by its lawful sons and daughters. May your meeting rally every black man to the side of Republican Spain. The liberation of Spain from the oppression of fascist reactionaries is not a private matter of the Spaniards, but the common cause of all advanced and progressive humanity.

(5) Paul Robeson was interviewed in the Daily Worker on on 22nd November 1937.

This is not a bolt out of the blue. Films eventually brought the whole thing to a head. I thought I could do something for the Negro race in the films; show the truth about them and about other people too. I used to do my part and go away feeling satisfied. Thought everything was O.K. Well, it wasn't. Things were twisted and changed - distorted. That made me think things out. It made me more conscious politically. Joining Unity Theatre means identifying myself with the working-class. And it gives me the chance to act in plays that say something I want to say about things that must be emphasized.

(6) Fred Copeman, was a member of the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote Paul Robeson in his autobiography, Reason in Revolt (1948)

Tappy told me that Paul Robeson and Charlotte Haldane had arrived and he was overwhelmed with his own picture of Robeson singing in the snow on Christmas Eve. Apparently the whole front was silenced as he sang, and his voice floated through the mountain passes and into the trenches in the deep snow. Many of the lads were unable to control their emotions.

(7) Paul Robeson, speech on lynching, Madison Square Garden (12th September, 1946)

This swelling wave of lynch murders and mob assaults against Negro men and women represents the ultimate limit of bestial brutality to which the enemies of democracy, be they German-Nazis or American Ku Kluxers, are ready to go in imposing their will. Are we going to give our America over to the Eastlands, Rankins and Bilbos? If not, then stop the lynchers! What about it. President Truman? Why have you failed to speak out against this evil? When will the federal government take effective action to uphold our constitutional guarantees? The leaders of this country can call out the Army and Navy to stop the railroad workers, and to stop the maritime workers - why can't they stop the lynchers?

(8) Paul Robeson, Here I Stand (1958)

It has been alleged that I am part of some kind of international conspiracy. I am not and never have been involved in any international conspiracy or any other kind, and do not know anyone who is. My belief in the principles of scientific socialism, my deep conviction that for all mankind a socialist society represents an advance to a higher stage of life - that it is a form of society represents an advance to a higher stage of life - that it is a form of society which is economically, socially, culturally, and ethically superior to a system based upon production for private profit have nothing in common with silly notions about 'plots' and 'conspiracies.'