Non-Intervention Agreement

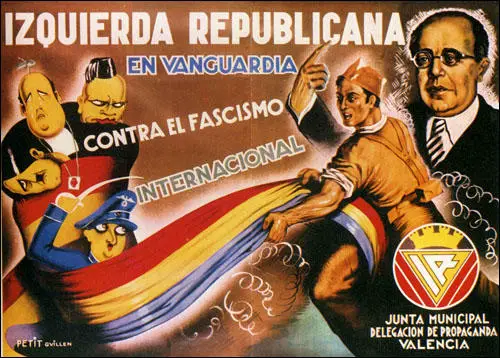

On 15th January 1936, Manuel Azaña helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left to fight the national elections due to take place the following month. This included the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party (PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party. The Popular Front, as the coalition became known, advocated the restoration of Catalan autonomy, amnesty for political prisoners, agrarian reform, an end to political blacklists and the payment of damages for property owners who suffered during the revolt of 1934. The Anarchists refused to support the coalition and instead urged people not to vote. (1)

Right-wing groups in Spain formed the National Front. This included the CEDA and the Carlists. The Falange Española did not officially join but most of its members supported the aims of the National Front. José Maria Gil Robles, the leader of the CEDA, encouraged by the political success of Adolf Hitler in Germany, employed a campaign that suggested he was willing to impose fascist solutions to solve Spain's problems. This was reinforced by a poster campaign that used various autocratic slogans. (2)

Popular Front Victory

The Spanish people voted on Sunday, 16th February, 1936. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. Popular Front parties won 47.3% (285 seats) and the National Front 46.4% (131 seats) with the centre parties winning 57 seats. Socialists (99 seats), Republican Left (87 seats), Republican Unionists (37 seats), Republican Left Catalonia (21 seats) and Communist (17 seats). Paul Preston has claimed: "The left had won despite the expenditure of vast sums of money - in terms of the amounts spent on propaganda, a vote for the right cost more than five times one for the left." (3)

The Popular Front government immediately upset the conservatives by releasing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. The most controversial decisions concerned the government's relationship with the Catholic Church. Azaña, the new prime minister, who was known for his strong anti-clerical views, announced that state support for the clergy and their involvement in education was brought to an end. Education was to be wholly secular and civil marriage and divorce was introduced. (4)

Outbreak of Spanish Civil War

Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy. In February 1936 Franco joined other Spanish Army officers, such as Emilio Mola, Juan Yague, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano and José Sanjurjo, in talking about what they should do about the Popular Front government. Mola became leader of this group and at this stage Franco was unwilling to fully commit himself to joining any possible uprising. (5)

As a result of the government's policies the wealthy took vast sums of capital out of the country. This created an economic crisis and the value of the peseta declined which damaged trade and tourism. With prices rising workers demanded higher wages. This situation led to a series of strikes in Spain. On the 10th May 1936 the conservative Niceto Alcala Zamora was ousted as president and replaced by Manuel Azaña. This disturbed the military as Zamora was "a conservative and catholic republican he could be seen as a counterbalance to anti-clerical liberals or reforming socialists." (6)

President Azaña appointed Diego Martinez Barrio as prime minister on 18th July 1936 and asked him to negotiate with the rebels. He contacted Emilio Mola and offered him the post of Minister of War in his government. He refused and when Azaña realized that the Nationalists were unwilling to compromise, he sacked Martinez Barrio and replaced him with José Giral. To protect the Popular Front government, Giral gave orders for arms to be distributed to left-wing organizations that opposed the military uprising. (7)

Dolores Ibarruri, the wife of a Spanish miner and a member of the Communist Party (PCE). Known by everybody as (La Pasionaria) she became the chief propagandist for the Republicans. In one speech she declared at a meeting for women: "It is better to be the widows of heroes than the wives of cowards!" On 18th July, 1936, she ended a radio speech with the words: "The fascists shall not pass! No Pasaran". This phrase eventually became the battle cry for the Republican Army. (8)

General Emilio Mola issued his proclamation of revolt in Navarre on 19th July, 1936. The coup got off to a bad start with José Sanjurjo being killed in an air crash on 20th July. The uprising was a failure in most parts of Spain but Mola's forces were successful in the Canary Islands and Morocco. The rebels also made good progress in the conservative regions of Navarre and Castile in northern Spain and in parts of Andalusia. However, Seville was the only city of importance to fall to them. (9)

General Franco, commander of the Army of Africa, joined the revolt and began to conquer southern Spain. This was followed by mass executions. Antony Beevor, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1982), has pointed out: "The local purge committees, usually composed of prominent right-wing citizens like the most prominent local landowner, the senior civil guard officer, a Falangist and, often, the priest... The committees inevitably inspired in neutrals a great fear of denunciation. All known or suspected liberals, freemasons and left-wingers were hauled in front of them... Their wrists were tied behind their backs with cord or wire before they were taken off for execution." (10)

Non-Intervention Agreement

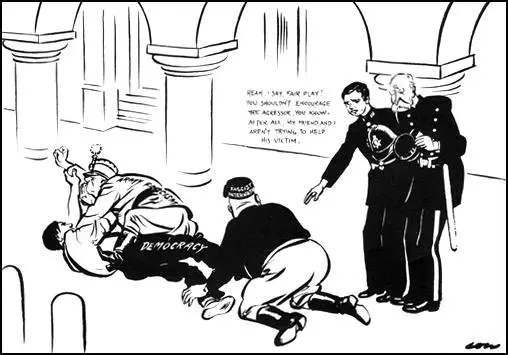

On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticised by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do. (11)

Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was aware that French armaments were inferior to those that Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action." (12)

In Britain sympathies were divided. Those on "the Left" saw it as "a Holy war, a Jehad in which the Spanish Government stood embattled against the forces of evil". Whereas "others, no less transported by emotion, who longed for the victory of the insurgents with an equal fervour, and saw in its achievement the conquest of anarchy and godlessness, and the triumphant reassertion of the principles of Christian life". It has been claimed that as a result "both parties ignored or excused the barbarities that were inflicted by their own champions." (13)

Eden told the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin that "The international situation is so serious that from day to day there was risk of some dangerous incident arising and even an outbreak of war could not be excluded." He argued that the two main aims of British policy should be "to secure peace" and to "keep this country out of war". This was viewed by the left another example of appeasing Hitler and Mussolini. Some historians have claimed that British ministers virtually blackmailed the French into accepting non-intervention. Frank McDonough believes that the "French were reluctant to become involved, not only out of fear of losing British support in a future European war, but because the Blum coalition was weak and feared active French involvement might precipitate a civil war on the streets of France." (14)

Paul Preston, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1986) has argued that "public opinion in Britain was overwhelmingly on the side of the Spanish Republic" and when defeat was certain, 70 per cent of those polled considered the Republic to be the the legitimate government. "However, among the small proportion of those who supported Franco, never more than 14 per cent, and often lower, were those who would make their crucial decisions. Where the Spanish war was concerned, Conservative decision-makers tended to let their class prejudices prevail over the strategic interests of Great Britain." (15)

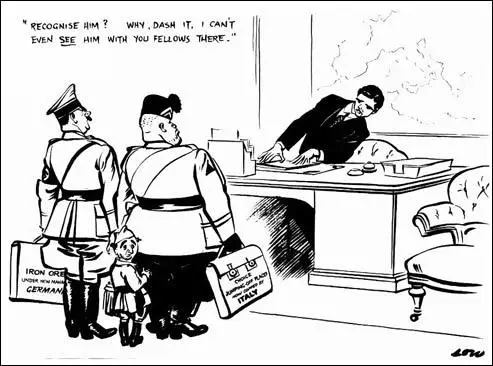

Baldwin called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. He also warned the French if they aided the Spanish government and it led to war with Germany, Britain would not help her. The first meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee met in London on 9th September 1936. Eventually 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Portugal, Sweden and Italy signed the Non-Intervention Agreement. Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Non-Intervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship owned by the Nationalists. (16)

Consequences of Non-Intervention Policy

The day after Germany signed the Non-Intervention Agreement, Adolf Hitler told his war minister, Field-Marshal Werner von Blomberg, that he wanted to give substantial aid to General Franco. (17) The British government was aware of this but "so long as non-intervention in Spain was imposed without too obvious infringements, so long as Germany remained less committed, politically and militarily, than Italy in the Civil War, some chance of a détente remained." (18)

Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, the Secretary of State for War, admitted that the government was fully aware that its Non-Intervention policy was unsuccessful. "What however it did do was to keep such intervention as there was entirely unofficial, to be denied or at least deprecated by the responsible spokesmen of the nation concerned, so that there was neither need nor occasion for any official action by Governments to support their nationals." (19)

In July 1936, the Popular Front government only controlled just over 50 per cent of Spain. By the end of the month, Adolf Hitler sent the the Nationalists 26 German fighter aircraft. He also sent 30 Junkers 52s from Berlin and Stuttgart to Morocco. Over the next couple of weeks the aircraft transported over 15,000 troops to Spain. By early September, 1936, General Emilio Mola and his troops gained control of San Sebastián. This was an important victory as it cut the Basque communications with France. (20)

In September 1936, Lieutenant Colonel Walther Warlimont of the German General Staff arrived as the German commander and military adviser to General Francisco Franco. The following month Warlimont suggested that a German Condor Legion should be formed to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The initial force comprised about a hundred aircraft and was supported by anti-aircraft and anti-tank units and four tank companies. The Condor Legion, under the command of General Hugo Sperrle, was an autonomous unit responsible only to Franco. The legion amounted to some 3,800 men at the beginning, later to 5,000. (21)

The Soviet Union were the main suppliers of military aid to the Republican Army. This included 1,000 aircraft, 900 tanks, 1,500 artillery pieces, 300 armoured cars, 15,000 machine-guns, 30,000 automatic firearms, 30,000 mortars, 500,000 riles and 30,000 tons of ammunition. The Soviets expected the Republicans to pay for these military supplies in gold. On the outbreak of the war Spain had the world's fourth largest reserves of gold. During the war approximately $500 million, or two-thirds of Spain's gold reserves, were shipped to the Soviet Union. (22)

General Francisco Franco came under pressure from Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to obtain a quick victory by taking Madrid. He eventually decided to use 30,000 Italians and 20,000 legionnaires to attack Guadalajara, forty miles northeast of the capital. On 8th March the Italian Corps took Guadalajara and began moving rapidly towards Madrid. Four days later the Republican Army with Soviet tanks counter-attacked. The Italians suffered heavy losses and those left alive were forced to retreat on 17th March, 1937. The Republicans also captured documents which proved that the Italians were regular soldiers and not volunteers. However, the Non-Intervention Committee refused to accept the evidence and the Italian government boldly announced that no Italian soldiers would be withdrawn until the Nationalist Army was victorious. (23)

On 21st September 1938, Juan Negrin announced at the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. This was not a great sacrifice as there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery. (24)

It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others) in the Spanish Civil War. The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. (25)

Primary Sources

(1) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

When the Spanish Republican Government was formed in 1936 the news was received enthusiastically by Socialists in Britain. Many of the new Government members were well known in the international Socialist movement. The emergence of a democratic regime in Spain was a bright light in a gloomy period when war had raped Abyssinia, and Germany had repudiated the Locarno Treaty. On the sudden outbreak of civil war in July, 1936, Socialist movements in all those European countries where they were allowed to exist immediately took steps to consider whether intervention should be demanded.

The Fascist attack was regarded as aggression by the majority of thinking people. Leon Blum, at the time Prime Minister of France, was greatly concerned in this matter. As political head of a nation which was bordered by Spain he had to consider the danger of some of the belligerents being forced over the border; as a Socialist he had a duty to go to the help of his comrades, members of a legally elected Government, who had been attacked by men organized and financed from outside Spanish home territory.

In Britain, although the Government was against intervention, the Labour Party had to face the strong demands from the rank-and-file for concrete action. The three executives met at Transport House to consider the next move, and I was present as a member of the Parliamentary Executive. We were largely influenced by Blum's policy. He had decided that he could not risk committing his country to intervention. Germany and Italy were supplying arms, aircraft, and men to the Spanish Fascists, and Blum considered that any action on the Franco-Spanish border on behalf of the Republican Government would bring imminent danger of retaliatory moves by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany on France's eastern flank. As a result of this French attitude Herbert Morrison's appeal in favour of intervention received little support. Although, like him, I was inclined towards action I pointed out that if France failed to intervene it would be a futile gesture to advise that Britain should do so. We had the recent farce of sanctions against Italy as a warning.

(2) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (22nd February, 1938)

Our policy has been consistently directed to one aim - to maintain the peace of Europe by confining the war to Spain. Although it is true that intervention has been going on and is going on, in spite of the non-intervention agreement, yet it is also true that we have succeeded in achieving the object at the back of our policy, and we shall continue that object and policy as long as we feel there is reasonable hope of avoiding a spread of the conflict.

I do not believe that it is fantastic to think that we can continue this policy successfully, even to the end. The situation is serious, but it is not hopeless. Although it may be true that various countries or various Governments desire to see one side or the other side in Spain winning, there is not a country or a Government that wants to see a European war.

Since that is so, let us keep cool heads. Neither say nor do anything to precipitate a disaster which everybody really wishes to avoid.

When I think of the experience of German officers, the loss of life and the mutilation of men on the Deutschland, and the natural feelings of indignation and resentment that must have been aroused by such incidents, I must say that I think the German Government in wisely withdrawing their ships and then declaring the incident closed have shown a degree of restraint which we ought to be able to recognise.

I make an earnest appeal to those who hold responsible positions both in this country and abroad to weigh their words very carefully before they utter them on this matter, bearing in mind the consequences that may flow from some rash or thoughtless phrase. By exercising caution and patience and self-restraint we may yet be able to save the peace of Europe.

(3) Leon Blum, speech in the House of Representatives (6th December 1936)

Our foreign policy has been inspired by two simple principles: the determination to place France's interests above all others, and the conviction that France has no greater interest than that of peace, the certainty that peace for France is inseparable from peace for Europe. All the groups in the majority, and I am sure the whole House, are in agreement on these principles.

I shall not accuse anyone of trying to push us directly or indirectly toward war. Everyone in France wants peace. Everyone is equally ardent in expressing this wish, and I have no doubt, equally sincere. Everyone understands that neither war, nor consequently peace, can today be contained within national borders, and that a people can only preserve itself from the scourge by contributing to preserve all others from it.

However, gentlemen, despite this fundamental agreement, I am obliged to remark that our questioners have been rather discreet in praising us. Most of the opposition speakers, and first and foremost my friend Paul Reynaud, have come forward in turn to claim that because of the composition of the majority and the demands of our domestic program we are condemned, in the international sphere, either to self-contradiction or to impotence. And furthermore, on what may be the gravest of current issues - it is certainly the most emotional - the Spanish question, our common desire for peace nonetheless leaves us in disagreement, in practice, with one of the groups of the majority, the group made up by the Communist party.

I have dealt with this question elsewhere. I have never spoken of it before the House. Although, in reality, I have nothing to add to the declarations of my friend Mr. Yvon Delbos (Radical-Socialist Party), with whom I have always shared the most loyal and affectionate sense of solidarity, the House will no doubt permit me to furnish some personal explanations. I repeat, as was said by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, that as far as we are concerned, there is only one legal government in Spain, or, to put it better, only one government. The principles of what might be called democratic law coincide in this respect with the undisputed rules of international law.

I recognize that France's direct interest includes and calls for the presence of a friendly government on Spanish soil, and one that is free of certain other European influences. I have no hesitation in agreeing that the establishment in Spain of a military dictatorship too closely bound by links of indebtedness to Germany and Italy would represent not only an attack on the cause of international democracy, but a source of anxiety - I do not wish to put it more strongly - for French security, and hence a threat to peace. In that respect, I agree with the argument that Mr. Gabriel Peri (Communist Party) presented to the House. In fact, I deplore that such an obvious truth was not perceived from the start by all of French and international public opinion, and that it has been obscured by Party passion and resentment. Let me add - and I do not think that anyone in this House will pay me the insult of being surprised - that I do not intend for a single moment to deny the personal friendship tying me to the Spanish socialists, and to many republicans: it still attaches me to them, despite the bitter disappointment they feel and express about me today.

I know all that. I feel it all. And to take this sort of public confession through to its conclusion, I shall add that since 8 August, a certain number of our hopes and expectations have in fact been disappointed; that all of us were hoping that the noninterference pact, which we had put into effect in advance, would be signed more promptly; that we were counting on the other governments' keeping more closely to their commitments. The policy of noninterference, in many respects, has not produced all we expected of it. True. But, gentlemen, is that a reason to condemn it? Here we must, all of us, make a very thorough analysis.

If it is true that in the name of international freedom, and in the name of French security, we must at all costs prevent the rebellion on Spanish soil from succeeding, then I declare that the conclusions reached by Mr. Gabriel Peri and Mr. Thorez (Communist Party)do not go far enough. It is not enough to denounce the noninterference agreement. It is not enough to reestablish free arms trade between France and Spain. Free arms trade between France and Spain would not be adequate aid, far from it. No! To assure the success of Republican legality in Spain, we would have to go further, much further. We would have to take a much greater step.

In conditions such as we have them at present, the truth of the matter is - and events have proved it - that the arming of a government can really only be done by another government. To be really effective, aid must be governmental. This is true from the point of view of materials, and from the point of view of recruitment. It would have to include, by way of equipment, levying arms from our own stocks, and byway of a sign-up of volunteers, levying troops from our units.

(4) The Manchester Guardian (25th July 1936)

A pessimistic view is taken here of events in Spain. There is no indication yet whether the Government or the insurgents are likely to prevail. Everything points to a protracted and sanguinary civil war.

The insurgents have the advantage of getting outside help whereas the Government is getting none. The latter has applied to the French Government for permission to import arms from France, but so far at least permission has not been given. The insurgents, on the other hand, are being assisted by the Italians and Germans.

During the last few weeks large numbers of Italian and German agents have arrived in Morocco and the Balearic Islands. These agents are taking part in military activities and are also exercising a certain political influence.

For the insurgents the belief that they have the support of the two great 'Fascist Powers' is an immense encouragement. But it is also more than an encouragement, for many of the weapons now in their hands are of Italian origin. This is particularly so in Morocco.

The German influence is strongest in the Balearic Islands. Germany has a great interest in the victory of the insurgents.

Apparently she hopes to secure concession in the Balearic Islands from them when they are in power. These islands play an important part in German plans for the future development of sea-power in the Mediterranean.

The civil war is of particular interest to Germany because the victory of the insurgents would open the prospect (closed by Anglo-French collaboration and by the existence of a pro-British, pro-French, and pro-League Spanish Republic) of action in Western Europe. That is to say, a 'Fascist' Spain would, for Germany, be a means of 'turning the French flank' and of playing a part in the Mediterranean.

On the Spanish mainland Germany disposed of a numerous and extremely well-organised branch of the National Socialist party. This branch has been strongly reinforced by newcomers from Germany during the last few weeks. She also disposes of a powerful organization for political and military espionage, which works behind a diplomatic and educational facade. Barcelona in particular has a large German population, the greater part of which is at the disposal of the National Socialists.

The fate of Morocco is naturally of the highest interest to Germany, for if the insurgents are victorious she may hope to secure territorial concessions in Morocco and therefore a foothold in Northern Africa.

(5) Resolution passed by the British Battalion on 27th March 1937.

We the members of the British working class in the British Battalion of the International Brigade now fighting in Spain in defence of democracy, protest against statements appearing in certain British papers to the effect that there is little or no interference in the civil war in Spain by foreign Fascist Powers.

We have seen with our own eyes frightful slaughter of men, women, and children in Spain. We have witnessed the destruction of many of its towns and villages. We have seen whole areas which have been devastated. And we know beyond a shadow of doubt that these frightful deeds have been done mainly by German and Italian nationals, using German and Italian aeroplanes, tanks, bombs, shells, and guns.

We ourselves have been in action repeatedly against thousands of German and Italian troops, and have lost many splendid and heroic comrades in these battles.

We protest against this disgraceful and unjustifiable invasion of Spain by Fascist Germany and Italy; an invasion in our opinion only made possible by the pro-Franco policy of the Baldwin Government in Britain. We believe that all lovers of freedom and democracy in Britain should now unite in a sustained effort to put an end to this invasion of Spain and to force the Baldwin Government to give to the people of Spain and their legal Government the right to buy arms in Britain to defend their freedom and democracy against Fascist barbarianism. We therefore call upon the General Council of the T.U.C. and the National Executive Committee of the Labour party to organise a great united campaign in Britain for the achievement of the above objects.

We denounce the attempts being made in Britain by the Fascist elements to make people believe that we British and other volunteers fighting on behalf of Spanish democracy are no different from the scores of thousands of conscript troops sent into Spain by Hitler and Mussolini. There can be no comparison between free volunteers and these conscript armies of Germany and Italy in Spain.

Finally, we desire it to be known in Britain that we came here of our own free will after full consideration of all that this step involved. We came to Spain not for money, but solely to assist the heroic Spanish people to defend their country's freedom and democracy. We were not gulled into coming to Spain by promises of big money. We never even asked for money when we volunteered. We are perfectly satisfied with our treatment by the Spanish Government; and we still are proud to be fighting for the cause of freedom in Spain. Any statements to the contrary are foul lies.

(6) The Manchester Guardian (13th August 1936)

It is evident that the German Government does not want any more trouble in connection with the Spanish civil war. It seems to believe that further support of the rebels will injure Franco-German and, above all, Anglo-German relations, and, much as it desires a rebel victory and concerned as it is over what it believes to be the spread of so-called 'Bolshevism' in Europe, it prefers, for the moment at least, not to take any risks where no vital interests of its own are involved.

Interference with the internal affairs of other countries is a conscious instrument of German foreign policy, and is for that very reason used only when it is safe to do so, or, if any risks are taken, only when the end in view is regarded as being of vital interest to Germany. It is therefore unlikely that Germany will put any further obstacles in the way of an agreement for non-intervention.

The Italian reply to the French proposals is favourable in so far as it accepts the text of these proposals in full, but unfavourable in so far as the Italians wish to add three conditions - that no subsidies be raised on behalf of either Spanish faction, that no subjects of the Powers who sign the agreement join either faction as volunteers, and that an International Committee superintend the working of the agreement.

It is difficult, if not impossible, in a democratic country to stop subscriptions for any cause that is not illegal. As for volunteers, the French are prepared to forbid organised recruiting, but they have no means of preventing French subjects from going to Spain as ordinary visitors and then joining either faction. It does not appear that many volunteers have taken part in the civil war except that a certain number of German émigrés who are trained pilots or machine-gunners have offered their services to the loyalists. The French do not think that subscriptions or volunteers for ambulance work in Spain ought to be prohibited. To the Italian proposal for a committee of control the French raise no objection.

According to information received here, Russia has already stopped subscription on behalf of the Spanish 'loyalists'. The difficulties raised by Portugal are being met by Anglo-French assurances that she need feel no anxiety lest her territory be violated. Germany, it seems, is no longer an obstacle to an agreement. Italy, therefore, stands alone as the one obstructive Power. But it is believed that the difficulties raised by the conditions she has made will be overcome.

(7) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952)

In the course of the next three years Germany sent men and military supplies, including experts and technicians of all kinds and the famous Condor Air Legion. German aid to Franco was never on a major scale, never sufficient to win the war for him or even to equal the forces sent by Mussolini, which in March 1937 reached the figure of sixty to seventy thousand men. Hitler's policy, unlike Mussolini's, was not to secure Franco's victory, but to prolong the war. In April 1939, an official of the German Economic Policy Department, trying to reckon what Germany had spent on help to Franco up to that date, gave a round figure of five hundred million Reichsmarks, not a large sum by comparison with the amounts spent on rearmament. But the advantages Germany secured in return were disproportionate - economic advantages (valuable sources of raw materials in Spanish mines); useful experience in training her airmen and testing equipment such as tanks in battle conditions; above all, strategic and political advantages.

It only needed a glance at the map to show how seriously France's position was affected by events across the Pyrenees. A victory for Franco would mean a third Fascist State on her frontiers, three instead of two frontiers to be guarded in the event of war. France, for geographical reasons alone, was more deeply interested in what happened in Spain than any other of the Great Powers, yet the ideological character of the Spanish Civil War divided, instead of uniting, French opinion. The French elections shortly before the outbreak of the troubles in Spain had produced the Left-wing Popular Front Government of Leon Blum. So bitter had class and political conflicts grown in France that - as in the case of the Franco-Soviet Treaty - foreign affairs were again subordinated to internal faction, and many Frenchmen were prepared to support Franco as a way of hitting at their own Government.

(8) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1959)

Though German aid to Franco never equalled that given by Italy, which dispatched between sixty and seventy thousand troops as well as vast supplies of arms and planes, it was considerable. The Germans estimated later that they spent half a billion marks on the venture 37 besides furnishing planes, tanks, technicians and the Condor Legion, an Air Force unit which distinguished itself by the obliteration of the Spanish town of Guernica and its civilian inhabitants. Relative to Germany's own massive rearmament it was not much, but it paid handsome dividends to Hitler.

It gave France a third unfriendly fascist power on its borders. It exacerbated the internal strife in France between Right and Left and thus weakened Germany's principal rival in the West. Above all it rendered impossible a rapprochement of Britain and France with Italy, which the Paris and London governments had hoped for after the termination of the Abyssinian War, and thus drove Mussolini into the arms of Hitler.

From the very beginning the Fuehrer's Spanish policy was shrewd, calculated and far-seeing. A perusal of the captured German documents makes plain that one of Hitler's purposes was to prolong the Spanish Civil War in order to keep the Western democracies and Italy at loggerheads and draw Mussolini toward him.

(9) Ulrich von Hassell, German Ambassador in Italy (December 1936)

The role played by the Spanish conflict as regards Italy's relations with France and England could be similar to that of the Abyssinian conflict, bringing out clearly the actual, opposing interests of the powers and thus preventing Italy from being drawn into the net of the Western powers and used for their machinations. The struggle for dominant political influence in Spain lays bare the natural opposition between Italy and France; at the same time the position of Italy as a power in the western Mediterranean comes into competition with that of Britain. All the more clearly will Italy recognize the advisability of confronting the Western powers shoulder to shoulder with Germany.

(10) Emanuel Shinwell initially argued that the British government should give support to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his visit to Spain in his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

While the war was at its height several of us were invited to visit Spain to see how things were going with the Republican Army. The fiery little Ellen Wilkinson met us in Paris, and was full of excitement and assurance that the Government would win. Included in the party were Jack Lawson, George Strauss, Aneurin Bevan, Sydney Silverman, and Hannen Swaffer. We went by train to the border at Perpignan, and thence by car to Barcelona where Bevan left for another part of the front.

We travelled to Madrid - a distance of three hundred miles over the sierras - by night for security reasons as the road passed through hostile or doubtful territory. It was winter-time and snowing hard. Although our car had skid chains we had many anxious moments before we arrived in the capital just after dawn. The capital was suffering badly from war wounds. The University City had been almost destroyed by shell fire during the earlier and most bitter fighting of the war.

We walked along the miles of trenches which surrounded the city. At the end of the communicating trenches came the actual defence lines, dug within a few feet of the enemy's trenches. We could hear the conversation of the Fascist troops crouching down in their trench across the narrow street. Desultory firing continued everywhere, with snipers on both sides trying to pick off the enemy as he crossed exposed areas. We had little need to obey the orders to duck when we had to traverse the same areas. At night the Fascist artillery would open up, and what with the physical effects of the food and the expectation of a shell exploding in the bedroom I did not find my nights in Madrid particularly pleasant.

It is sad and tragic to realize that most of the splendid men and women, fighting so obstinately in a hopeless battle, whom we met have since been executed, killed in action - or still linger in prison and in exile. The reason for the defeat of the Spanish Government was not in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people. They had a few brief weeks of democracy with a glimpse of all that it might mean for the country they loved. The disaster came because the Great Powers of the West preferred to see in Spain a dictatorial Government of the right rather than a legally elected body chosen by the people. The Spanish War encouraged the Nazis both politically and as a proof of the efficiency of their newly devised methods of waging war. In the blitzkrieg of Guernica and the victory by the well-armed Fascists over the helpless People's Army were sown the seeds for a still greater Nazi experiment which began when German armies swooped into Poland on 1st September, 1939.

It has been said that the Spanish Civil War was in any event an experimental battle between Communist Russia and Nazi Germany. My own careful observations suggest that the Soviet Union gave no help of any real value to the Republicans. They had observers there and were eager enough to study the Nazi methods. But they had no intention of helping a Government which, was controlled by Socialists and Liberals. If Hitler and Mussolini fought in the arena of Spain as a try-out for world war Stalin remained in the audience. The former were brutal; the latter was callous. Unfortunately the latter charge must also be laid at the feet of the capitalist countries as well.

(11) Tom Murray, Voices From the Spanish Civil War (1986)

It was the view of everybody who went to Spain to fight for the Republic that if Franco were defeated Mussolini would collapse. And if Mussolini collapsed it would undermine Hitler and probably destroy the danger of a Second World War. That was our view. It would create a major international crisis if we had been able to defeat the invasion of Spain. Because, as I've said earlier on, it was only a civil war for a short period and then it became a question of repelling the invasion of foreign elements such as the Italians and the Germans. As a matter of fact we never saw Spaniards at all on the other side. The people whom we were fighting were Italians, Italian conscripts sent by Mussolini. And the opposition that we had to contend with at home was that there was a widespread feeling that, "It can't happen here in Britain." But it did happen here, and we said it would happen here if we didn't defeat Franco. This aspect of the attitude of the people who went to Spain to fight should be clearly understood by everybody. It was an extremely important sentiment and conviction that the prospect of a Second World War would have been changed, if it ever occurred at all, if Mussolini had been defeated as a result of the collapse of Franco. But of course the so-called Non-Intervention policy was intervention in favour of Franco. The Republic of Spain was a properly constituted Government recognised internationally as being the legitimate Government of the Spanish people. And to prevent them from getting arms, purchasing arms, which they were prepared to do and pay for them, was of course simply part of the sabotage of the oppositon to Franco and bolstering up the Franco regime. This is an important aspect of the struggle in Spain that we must never forget, that this blighter Franco would never have existed for any length of time, and certainly would not have become a dictator, a Fascist dictator, if the so-called Non-Intervention policy, supported by the British and the French and the American Governments, hadn't occurred.

(12) Elizabeth Wilkinson, The Daily Worker (12th May 1937)

Hitler is celebrating Coronation Day with the biggest air-raid and bombardment on this city since the offensive began.

As I write this, at midday, in the centre of Bilbao, I can see a tremendous pall of black smoke darkening the bright sky.

There at La Campsa in the outskirts of Bilbao, a huge petrol dump is in flames. When I was out in this area I could feel the intense heat from the tremendous conflagration on the other side of the river, where the roads and the embankment were pock-marked by machine-gun bullets. And the dump is still flaming.

A little later a house in front of where I was standing was completely destroyed. The people who had lived there talked to me just a little, and one of the things they said was: 'I should like to put the London Non-Intervention Committee right in the middle of all this.'

I counted nine bombers and seven chasers come over. They bomb and machine-gun everything the pilots can set eyes on. They have even bombed a herd of cattle coming along one of the roads into Bilbao.

The people streaming in along those roads say they are strewn with dead and dying cows.

Already the Nazi pilots have dropped thirty big explosive bombs and hundreds of incendiary bombs on the city. They dropped them when you in England were laughing and shouting.

As I write the sirens, signalling a raid, are sounding again. I cannot tell what will happen.

(13) Emma Goldman, letter to the Manchester Guardian (28th October, 1936)

The sponsors of neutrality are trying to make the world believe that they are acting with the best intentions; they are trying to stave off a new world carnage. One might, by a considerable stretch of imagination, grant them the benefit of the doubt had their embargo on arms included both sides in this frightful civil war. But it is their one-sidedness which makes one question the integrity as well as the logic of the men proclaiming neutrality. It is not only the height of folly, it is also the height of inhumanity to sacrifice the larger part of the Spanish people to a small minority of Spanish adventurers armed with every modern device of war.

Moreover, the statesmen and political leaders of Europe know only too well that it is not out of love that Hitler and Mussolini have been supplying Franco and Mola with war material and money. Unless the men at the helm of the European Governments utterly lack clear thinking they must realise, as the rest of the thinking world already has, that there is a definite pact between the Spanish Fascists and their Italian and German confreres in the unholy alliance of Fascism. It is an open secret that the imperial ambitions of Hitler and Mussolini are not easily satisfied. If, then, they show such limitless generosity to their Spanish friends, it must be because of the colonial and strategic advantages definitely agreed to by Franco and Mola. It hardly requires much prophetic vision to predict that this arrangement would put all of Europe in the palm of Hitler and Mussolini.

Now the question is, Will France go back on her glorious revolutionary past by her tacit consent to such designs? Will England, with her liberal traditions, submit to such a degrading position? And, if not, will that not mean a new world carnage? In other words, the disaster neutrality is to prevent is going to follow in its wake. Quite another thing would happen if the anti-Fascist forces were helped to cope with the Fascist epidemic that is poisoning all the springs of life and health in Spain. For Fascism annihilated in Spain would also mean the cleansing of Europe from the black pest. And the end of Fascism in the rest of the world would also do away with the cause of war.

It is with neutrality as it is with people who can stand by a burning building with women and children calling for help or see a drowning man desperately trying to gain shore. No words can express the contempt all decent people would feel for such abject cowardice. Fortunately, there are not many such creatures in the world, m time of fire, floods, storm at sea, or at the sight of a fellow-being in distress human nature is at its best. Men, in danger to their own life and limb, rush into burning houses, throw themselves into the sea, and bravely carry their brothers to safety. Well, Spain is in flames. The Fascist conflagration is spreading. Is it possible that the liberal world outside Spain will stand by and see the country laid in ashes by the Fascist hordes? Or will they muster up enough courage to break through the bars of neutrality and come to the rescue of the Spanish people?

The main effect of neutrality so far has been the bitter disillusionment of the Spanish masses about France and England, whom until now they had valued and respected as democratic countries. They cannot grasp the obvious contradiction on the part of those who shout to the heavens that democracy must be preserved at all costs yet remain blind to the grave danger to democracy in the growth of Fascism. They insist that the latter is making ready to stab democracy in the back. The Spanish people quite logically have come to the conclusion that France and England are betraying their own past and that they have turned them over to the Fascist block like sheep for slaughter.

However, the Fascist conspiracy and the criminal indifferences of the so-called democratic countries will never bring the defenders of Spanish liberty to their knees. The callousness of the outside world has merely succeeded in steeling the will to freedom of the antifascist forces. And it has raised their courage to the point of utter disregard of the worst tribulations. Everywhere one goes one is impressed by the iron determination to fight until the last man and the last drop of blood. For well the Spanish workers know that peace and well-being will be impossible until Fascism has been driven off their fruitful soil.

(14) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

A few days later, the French closed the border. The democratic governments of France, Britain and the United States had embarked on their fatal policy of "non-intervention," placing an embargo on the shipment of arms to their sister republic of Spain, and in the name of neutrality standing by while the Axis powers blotted out democracy. From then on, volunteers found entering Spain heart-breakingly difficult. They had to climb the Pyrenees at night on foot, and sometimes were arrested by the French. Others came in by boat and some of these men were torpedoed and lost their lives before ever setting foot in Spain. We had been lucky enough to ride across the border in brilliant sunlight and in style.