Confederatión Espanola de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA)

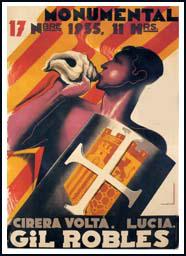

The Confederatión Espanola de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA) in Spain was founded by José Maria Gil Robles on 28th February, 1933 out of a collection of small right-wing parties opposed to the policies of Manuel Azaña and his Republican government.

In the 1933 elections, the CEDA won the most seats in the Cortes. President Niceto Alcalá Zamora refused to ask its leader, José Maria Gil Robles, to form a government. However, seven members of the CEDA served as ministers during the next three years.

In the elections of February 1936, 34.3 per cent of the vote went to the Popular Front, 33.2 per cent to the conservative parties and the rest to regional and centre parties. This gave the Popular Front 271 seats out of the 448 in the Cortes and Manuel Azaña was asked to form a new government.

The new government immediately upset the conservatives by realizing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy.

On the 10th May 1936 the conservative Niceto Alcala Zamora was ousted as president and replaced by the left-wing Manuel Azaña. Soon afterwards Spanish Army officers, including Emilio Mola, Francisco Franco and José Sanjurjo, began plotting to overthrow the Popular Front government. This resulted in the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War on 17th July, 1936.

Most members of CEDA supported the Nationalist Army in the war. However, General Franco was determined not to have competing right-wing parties in Spain and in April 1937 CEDA was dissolved.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlotte Haldane visited Spain with John Haldane in 1933. Charlotte later wrote about their experiences in her autobiography, Truth Will Out (1949)

The poverty was tragic. It was bad in Cordoba, worse in Granada, almost universal in Seville. Everywhere was economic, mental and physical depression. There was a lot of local opposition to the Republic, led and organized by the Church. The Government's natural idealistic incompetence was encouraged by systematic sabotage of every project attempted. The male working population was almost unanimously anarchist. The CNT and particularly the FAI were the strongest revolutionary parties. Socialism and Communism, or rather the Trotskyist deviation from that political creed, were in the minority. But almost the entire female population was firmly attached to Church politics, under the spiritual and political domination of the priesthood. Underneath all the beauty and glamour of the landscape, the architecture, the tradition, the romance, were rumblings of the political earthquake to come.