Spanish Civil War

Alfonso XII of Spain died three days before his 28th birthday, on 25th November 1885. He had been suffering from tuberculosis, but the immediate cause of his death was a recurrence of dysentery. (1) His only son, Alfonso XIII, was born six months later on 17th May, 1886. His mother, Maria Christina of Austria, served as his regent until his 16th birthday. During the regency, in 1898, Spain lost its colonial rule over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the United States as a result of the Spanish–American War. (2)

Alfonso became an increasingly autocratic ruler and at the end of July, 1909, there was a series of violent confrontations between the Spanish Army and members of the working classes of Barcelona and other cities of Catalonia, assisted by anarchists, socialists and republicans. Police and army casualties were eight dead and 124 wounded. It is estimated that as many as 150 civilians were killed. Five of the rebels were sentenced to death and executed and 59 received sentences of life imprisonment. (3)

Those executed included Ferrer Guardia, the headmaster and founder of the Escuela Moderna, a progressive school that attempted to provide a secular education and to teach radical social values. He was inspired by the works of William Godwin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, both of whom firmly rejected the idea of education brought about by means of compulsion. His school attracted international attention and prompted visits from George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Leo Tolstoy. His last words was "Aim well, my friends, you are not responsible. I am innocent; long live la Escuela Moderna". (4)

Alfonso managed to keep Spain neutral during the First World War. He became gravely ill during the 1918 flu pandemic. As the country was under no wartime censorship restrictions, his illness and subsequent recovery were reported to the world, while flu outbreaks in the belligerent countries were concealed. This gave the impression that Spain was the most-affected area and led to the pandemic being dubbed "the Spanish Flu." (5)

Abdication of Alfonso XIII

In 1920 entered the Rif War, in order to preserve its colonial rule over northern Morocco. Critics of the monarchy thought the war was an unacceptable loss of money and lives. Alfonso was in constant conflict with Spanish politicians. His anti-democratic views encouraged General Miguel Primo de Rivera, with the support of Alfonso, to lead a military coup in 1923. He promised to eliminate corruption and to regenerate Spain. In order to do this he suspended the constitution, established martial law and imposed a strict system of censorship. He initially said he would rule for only 90 days, however, he broke this promise and remained in power. (6)

Little social reform took place but he tried to reduce unemployment by spending money on public works. To pay for this Primo de Rivera introduced higher taxes on the rich. When they complained he changed his policies and attempted to raise money by public loans. This caused rapid inflation and after losing support of the army was forced to resign in January 1930. As Paul Preston has pointed out: "The Primo de Rivera dictatorship was to be regarded in later years as a golden age by the Spanish middle classes and became a central myth of the reactionary right. Paradoxically, however, its short-term effect was to discredit the very idea of authoritarianism in Spain." (7)

Alfonso XIII was advised that the only way to avoid large-scale violence was to go into exile. Alfonso agreed and left the country on 14th April, 1931. A general election was held on 28th June, 1931. It was the first time for nearly sixty years that free elections had been allowed in Spain. The Socialist Party (PSOE) and other left wing parties won an overwhelming victory. Niceto Alcala Zamora, a moderate Republican, became prime minister, but included in his cabinet several radical figures such as Manuel Azaña, Francisco Largo Caballero and Indalecio Prieto. (8)

On 16th October 1931, Azaña replaced Alcala Zamora as prime minister. With the support of the Socialist Party (PSOE) he attempted to introduce agrarian reform and regional autonomy. However, these measures were blocked in the Cortes. On 10th December 1931, Alcalá-Zamora was elected President by 362 votes out of the 410 in attendance. One of the government's first acts was to introduce income-tax for the first time. (9)

Manuel Azaña believed that the Catholic Church was responsible for Spain's backwardness. He defended the elimination of special privileges for the Church on the grounds that Spain had ceased to be Catholic. Azaña was criticized by the Catholic Church for not doing more to stop the burning of religious buildings in May 1931. He controversially remarked that burning of "all the convents in Spain was not worth the life of a single Republican". (10)

An attempted military coup led by José Sanjurjo took place on 10th August, 1932. Badly planned, it was easily defeated by a General Strike of CNT Union, UGT Union and the Communist Party (PCE). This action rallied support for Azaña's government. "This attack on the Republic by one of the senior members of the old regime, a monarchist general, benefited the government by generating a wave of pro-Republic fervour." It was now possible for him to get the Agrarian Reform Bill passed by the Cortes. (11)

However, the modernization programme of the Azaña administration was undermined by a lack of financial resources. The November 1933 elections saw the right-wing CEDA party win 115 seats whereas the Socialist Party only managed 58. CEDA, under the leadership of José Maria Gil Robles, now formed a parliamentary alliance with the Radical Party. Alejandro Lerroux became the new prime minister. (12)

This led to a general strike on 4th October 1934 and an armed rising in Asturias. Manuel Azaña was accused of encouraging these disturbances and on 7th October he was arrested and interned on a ship in Barcelona Harbour. However, no evidence could be found against him and he was released on 18th December. Azaña was also accused of supplying arms to the Asturias insurrectionaries. In March 1935, the matter was debated in the Cortes, where Azaña defended himself in a three-hour speech. On 6th April, 1935, the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees acquitted Azaña. (13)

The Popular Front

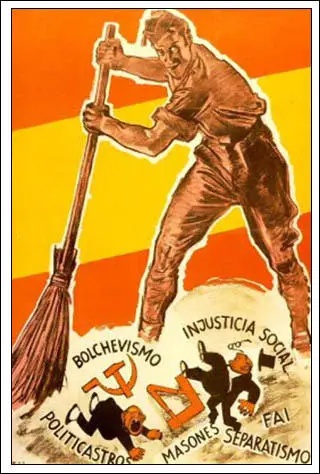

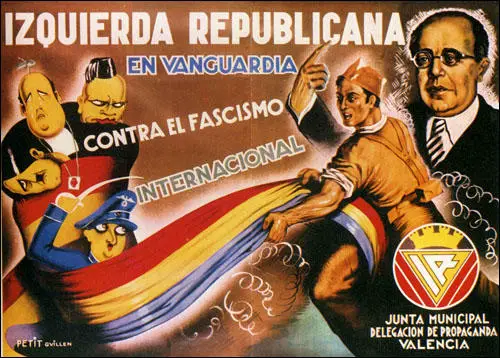

On 15th January 1936, Manuel Azaña helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left to fight the national elections due to take place the following month. This included the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party (PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party. The Popular Front, as the coalition became known, advocated the restoration of Catalan autonomy, amnesty for political prisoners, agrarian reform, an end to political blacklists and the payment of damages for property owners who suffered during the revolt of 1934. The Anarchists refused to support the coalition and instead urged people not to vote. (14)

Right-wing groups in Spain formed the National Front. This included the CEDA and the Carlists. The Falange Española did not officially join but most of its members supported the aims of the National Front. José Maria Gil Robles, the leader of the CEDA, encouraged by the political success of Adolf Hitler in Germany, employed a campaign that suggested he was willing to impose fascist solutions to solve Spain's problems. This was reinforced by a poster campaign that used various autocratic slogans. (15)

The Spanish people voted on Sunday, 16th February, 1936. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. Popular Front parties won 47.3% (285 seats) and the National Front 46.4% (131 seats) with the centre parties winning 57 seats. Socialists (99 seats), Republican Left (87 seats), Republican Unionists (37 seats), Republican Left Catalonia (21 seats) and Communist (17 seats). Paul Preston has claimed: "The left had won despite the expenditure of vast sums of money - in terms of the amounts spent on propaganda, a vote for the right cost more than five times one for the left." (16)

The Popular Front government immediately upset the conservatives by releasing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. The most controversial decisions concerned the government's relationship with the Catholic Church. Azaña, the new prime minister, who was known for his strong anti-clerical views, announced that state support for the clergy and their involvement in education was brought to an end. Education was to be wholly secular and civil marriage and divorce was introduced. (17)

Outbreak of Spanish Civil War

Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy. In February 1936 Franco joined other Spanish Army officers, such as Emilio Mola, Juan Yague, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano and José Sanjurjo, in talking about what they should do about the Popular Front government. Mola became leader of this group and at this stage Franco was unwilling to fully commit himself to joining any possible uprising. (18)

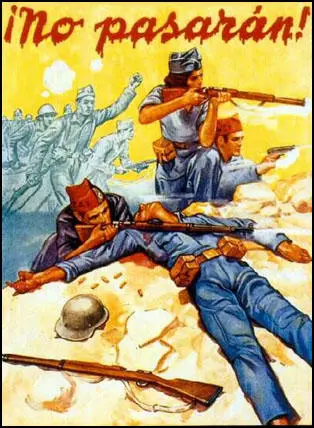

As a result of the government's policies the wealthy took vast sums of capital out of the country. This created an economic crisis and the value of the peseta declined which damaged trade and tourism. With prices rising workers demanded higher wages. This situation led to a series of strikes in Spain. On the 10th May 1936 the conservative Niceto Alcala Zamora was ousted as president and replaced by Manuel Azaña. This disturbed the military as Zamora was "a conservative and catholic republican he could be seen as a counterbalance to anti-clerical liberals or reforming socialists." (19)

President Azaña appointed Diego Martinez Barrio as prime minister on 18th July 1936 and asked him to negotiate with the rebels. He contacted Emilio Mola and offered him the post of Minister of War in his government. He refused and when Azaña realized that the Nationalists were unwilling to compromise, he sacked Martinez Barrio and replaced him with José Giral. To protect the Popular Front government, Giral gave orders for arms to be distributed to left-wing organizations that opposed the military uprising. (20)

Dolores Ibarruri, the wife of a Spanish miner and a member of the Communist Party (PCE). Known by everybody as (La Pasionaria) she became the chief propagandist for the Republicans. In one speech she declared at a meeting for women: "It is better to be the widows of heroes than the wives of cowards!" On 18th July, 1936, she ended a radio speech with the words: "The fascists shall not pass! No Pasaran". This phrase eventually became the battle cry for the Republican Army. (21)

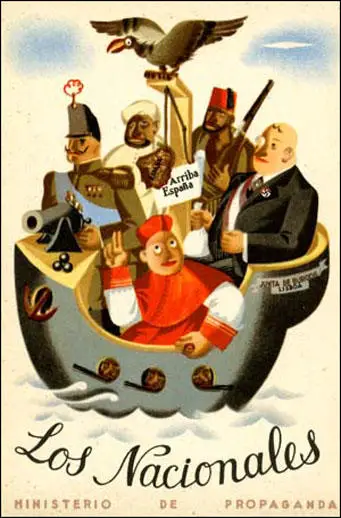

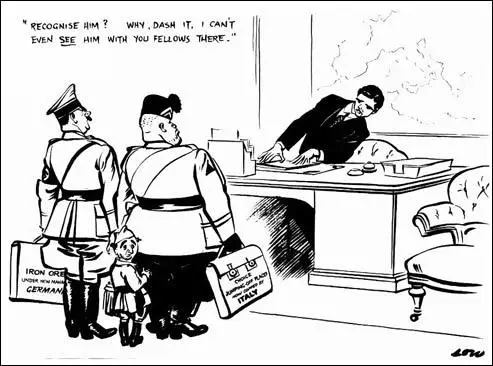

Catholic Church, Italians, Germans and Moors from Morocco. (1936)

General Emilio Mola issued his proclamation of revolt in Navarre on 19th July, 1936. The coup got off to a bad start with José Sanjurjo being killed in an air crash on 20th July. The uprising was a failure in most parts of Spain but Mola's forces were successful in the Canary Islands and Morocco. The rebels also made good progress in the conservative regions of Navarre and Castile in northern Spain and in parts of Andalusia. However, Seville was the only city of importance to fall to them. (22)

General Franco, commander of the Army of Africa, joined the revolt and began to conquer southern Spain. This was followed by mass executions. Antony Beevor, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1982), has pointed out: "The local purge committees, usually composed of prominent right-wing citizens like the most prominent local landowner, the senior civil guard officer, a Falangist and, often, the priest... The committees inevitably inspired in neutrals a great fear of denunciation. All known or suspected liberals, freemasons and left-wingers were hauled in front of them... Their wrists were tied behind their backs with cord or wire before they were taken off for execution." (23)

In Andalusia, the revolution was anarchist in inspiration. The socialist agricultural union, the FNTT, despite their numbers, were pushed aside by the extremists: "We in the socialist party were overwhelmed. What could we do? The people who took over thought only of violence. We were the strongest party here and yet we were helpless. We hardly ever met, to tell the truth. Those who took power had so little political consciousness that they robbed smallholders of the little they had." In many places, private property was abolished, along with the payment of debts to shopkeepers. (24)

Anarchists formed committees that took over from the landlord. In some cases large landowners were murdered where in other villages they were just sent away. In Castro del Rio, near Córdoba, the centre of anarchism, all private exchange of goods were banned. Franz Borkenau commented: "They did not want to get the good living of those whom they had expropriated, but to get rid of their luxuries." (25)

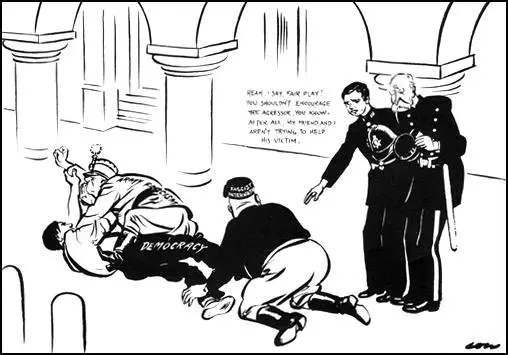

Atrocities were also carried out against supporters of the Popular Front government who were living in areas controlled by the Nationalist Army. This included the famous poet, Federico Garcia Lorca, whose home was in Granada. His brother-in-law Manuel Fernandez-Montesinos, was the socialist mayor of Granada. On 20th July, the rebels took control of the city and both men were arrested and soon after executed, along with 2,000 other supporters of the government. "The exact date of Lorca's death and the location of his remains are still disputed, but the cause is no mystery. In a society that was split down the middle Lorca was what we would call today a 'media personality', loved by one faction and hated by the other." (26)

President Manuel Azaña had no desire to be head of a government that was trying to militarily defeat another group of Spaniards. He attempted to resign but was persuaded to stay on by the Socialist Party and Communist Party who hoped that he was the best person to persuade foreign governments not to support the military uprising. Georgi Dimitrov, the head of Comintern, sent André Marty and Jacques Duclos to advise the government on forming a coalition government. It was his view that the Western powers would not tolerate a workers' government within their sphere of influence. (27)

Non-Intervention Agreement

On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticised by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do. (28)

Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was aware that French armaments were inferior to those that Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action." (29)

In Britain sympathies were divided. Those on "the Left" saw it as "a Holy war, a Jehad in which the Spanish Government stood embattled against the forces of evil". Whereas "others, no less transported by emotion, who longed for the victory of the insurgents with an equal fervour, and saw in its achievement the conquest of anarchy and godlessness, and the triumphant reassertion of the principles of Christian life". It has been claimed that as a result "both parties ignored or excused the barbarities that were inflicted by their own champions." (30)

Eden told the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin that "The international situation is so serious that from day to day there was risk of some dangerous incident arising and even an outbreak of war could not be excluded." He argued that the two main aims of British policy should be "to secure peace" and to "keep this country out of war". This was viewed by the left another example of appeasing Hitler and Mussolini. Some historians have claimed that British ministers virtually blackmailed the French into accepting non-intervention. Frank McDonough believes that the "French were reluctant to become involved, not only out of fear of losing British support in a future European war, but because the Blum coalition was weak and feared active French involvement might precipitate a civil war on the streets of France." (31)

Paul Preston, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1986) has argued that "public opinion in Britain was overwhelmingly on the side of the Spanish Republic" and when defeat was certain, 70 per cent of those polled considered the Republic to be the the legitimate government. "However, among the small proportion of those who supported Franco, never more than 14 per cent, and often lower, were those who would make their crucial decisions. Where the Spanish war was concerned, Conservative decision-makers tended to let their class prejudices prevail over the strategic interests of Great Britain." (32)

Baldwin called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. He also warned the French if they aided the Spanish government and it led to war with Germany, Britain would not help her. The first meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee met in London on 9th September 1936. Eventually 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Portugal, Sweden and Italy signed the Non-Intervention Agreement. Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Non-Intervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship owned by the Nationalists. (33)

The day after Germany signed the Non-Intervention Agreement, Adolf Hitler told his war minister, Field-Marshal Werner von Blomberg, that he wanted to give substantial aid to General Franco. (34) The British government was aware of this but "so long as non-intervention in Spain was imposed without too obvious infringements, so long as Germany remained less committed, politically and militarily, than Italy in the Civil War, some chance of a détente remained." (35)

Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, the Secretary of State for War, admitted that the government was fully aware that its Non-Intervention policy was unsuccessful. "What however it did do was to keep such intervention as there was entirely unofficial, to be denied or at least deprecated by the responsible spokesmen of the nation concerned, so that there was neither need nor occasion for any official action by Governments to support their nationals." (36)

International Brigades

In August 1936, Harry Pollitt, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, arranged for Tom Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the CPGB during the Civil War. Wintringham, along with Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, went out to Spain with the first ambulance unit paid for by the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, a Popular Front organisation supported by the Labour Party. According to the Daily Worker, it left Victoria Station to the cheers of 3,000 supporters who had marched from Hyde Park to see them off led by the Labour mayors from East London boroughs. (37)

While in Barcelona he developed the idea of a volunteer international legion to fight on the side of the Republican Army. He commented: "I believed in the idea of an international legion. Militias can do a lot. But a larger-scale example of military knowledge and discipline, and larger-scale results, are needed too. You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in. You need things big enough to be worth putting in the newspapers." (38)

In September 1936, Tom Wintringham wrote to Harry Pollitt that he had arranged for Nat Cohen, a Jewish clothing worker from Stepney, to establish "a Tom Mann centuria which will include 10 or 12 English and can accommodate as many likely lads as you can send out... I propose to join it, provided I can still write for the Daily Worker. I believe that full political value can only be got from it (and that's a lot) if its English contingent becomes stronger. 50 is not too many." (39)

Maurice Thorez, the French Communist Party leader, also had the idea of an international force of volunteers to fight for the Republic. At a meeting of Comintern, in an impassioned speech by Georgi Dimitrov, it was suggested the Communist parties in all countries should establish volunteer battalions. Joseph Stalin agreed and the Comintern began organising the formation of International Brigades. An international recruiting centre was set up in Paris and a training base at Albacete in Spain. (40)

1936. Left to right: Sid Avner, Nat Cohen, Ramona, Tom Winteringham,

George Tioli, Jack Barry and David Marshall.

Stalin played an important role in the formation of the International Brigades. As Gary Kern has pointed out in A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "To start the ball rolling, he (Stalin) ordered that 500-600 foreign Communists living as refugees in the USSR, personae non grata in their own countries, be rounded up and sent to fight in Spain. This action not only rid him of a long-term irritant, but also laid the foundation for the International Brigades. The Comintern, which officially promulgated the policy of non-intervention, was enlisted to process young men in foreign countries wishing to join the Brigades. The word went out that the various Communist parties would facilitate their transport to Spain; in each CP a Comintern representative directed the program." (41)

Franklin D. Roosevelt was very sympathetic to the Republican cause. So was his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, and several members of his government, including Henry Morgenthau, secretary of the treasury, Henry A. Wallace, secretary for agriculture, Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior and Summer Welles, the assistant secretary of state. However, during the election campaign, Roosevelt made a commitment that he would not allow America to become involved in European conflicts. Cordell Hull, secretary of state, insisted that Roosevelt kept to this policy. (42)

Some people in America felt so strongly about this that they were willing to go to Spain to fight to protect democracy. As a result, the Abraham Lincoln Battalion was formed. An estimated 3,000 men fought in the battalion. Of these, over 1,000 were industrial workers (miners, steel workers, longshoremen). Another 500 were students or teachers. Around 30 per cent were Jewish and 70 per cent were between 21 and 28 years of age. The majority were members of the American Communist Party, whereas others came from the Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party. The first volunteers sailed from New York City on 25th December, 1936. (43)

Bill Bailey wrote to his mother explaining his decision to join the Abraham Lincoln Battalion: "You see Mom, there are things that one must do in this life that are a little more than just living. In Spain there are thousands of mothers like yourself who never had a fair shake in life. They got together and elected a government that really gave meaning to their life. But a bunch of bullies decided to crush this wonderful thing. That's why I went to Spain, Mom, to help these poor people win this battle, then one day it would be easier for you and the mothers of the future. Don't let anyone mislead you by telling you that all this had something to do with Communism. The Hitlers and Mussolinis of this world are killing Spanish people who don't know the difference between Communism and rheumatism. And it's not to set up some Communist government either. The only thing the Communists did here was show the people how to fight and try to win what is rightfully theirs." (44)

A large number of African-Americans joined the battalion. Canute Frankson explained his decision in a letter written to his parents: "I'm sure that by this time you are still waiting for a detailed explanation of what has this international struggle to do with my being here. Since this is a war between whites who for centuries have held us in slavery, and have heaped every kind of insult and abuse upon us, segregated and Jim-Crowed us; why I, a Negro who have fought through these years for the rights of my people, am here in Spain today? Because we are no longer an isolated minority group fighting hopelessly against an immense giant. Because, my dear, we have joined with, and become an active part of, a great progressive force, on whose shoulders rests the responsibility of saving human civilization from the planned destruction of a small group of degenerates gone mad in their lust for power. Because if we crush Fascism here we'll save our people in America, and in other parts of the world from the vicious persecution, wholesale imprisonment, and slaughter which the Jewish people suffered and are suffering under Hitler's Fascist heels." (45)

Americans were forbidden to travel to Spain to fight for the Republicans. The Manchester Guardian reported in April 1937: "Twenty-nine Americans who are alleged to have tried to cross the French frontier into Spain to enlist with the Spanish Government forces were detained last night at Muret between Toulouse and the Spanish frontier. The Americans had landed at Havre maintaining, it is stated, that they were genuine tourists. They have been brought to Toulouse for questioning." (46)

Efforts by the Roman Catholic Church in the United States to enlist support for Franco's Spain was unsuccessful. Despite the anti-clericism of the Republicans, that resulted in the killing of priests and the burning of churches during the first months of the war, a public opinion poll revealed that forty-eight per cent of Roman Catholics in the United States supported the Popular Front government. The American Committee for Spanish Nationalist Relief, sponsored by the Church, folded before it had collected 30,000 dollars - all of which had to be used for administrative expenses. Roosevelt later admitted that America's non-intervention policy "had been a grave mistake" because it "contravened old American principles and invalidated established international law." (47)

Socialists and Communists all over Europe formed International Brigades and went to Spain to protect the Popular Front government. Men who fought with the Republican Army included George Orwell, André Marty, Christopher Caudwell, Jack Jones, Len Crome, Oliver Law, Tom Winteringham, Joe Garber, Lou Kenton, Bill Alexander, David Marshall, Alfred Sherman, William Aalto, Hans Amlie, Bill Bailey, Robert Merriman, Steve Nelson, Walter Grant, Alvah Bessie, Joe Dallet, David Doran, John Gates, Harry Haywood, Oliver Law, Edwin Rolfe, Milton Wolff, Hans Beimler, Frank Ryan, Emilo Kléber, Ludwig Renn, Gustav Regler, Ralph Fox, Sam Wild and John Cornford.

A total of 59,380 volunteers from fifty-five countries served during the Spanish Civil War. This included the following: French (10,000), German (5,000), Polish (5,000), Italian (3,350), American (2,800), British (2,000), Yugoslavian (1,500), Czech (1,500), Canadian (1,000), Hungarian (1,000) and Scandinavian (1,000). Battalions established included the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, British Battalion, Connolly Column, Dajakovich Battalion, Dimitrov Battalion, Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, George Washington Battalion, Mickiewicz Battalion and Thaelmann Battalion. (48)

The Civil War: Stalemate

In July 1936, the Popular Front government only controlled just over 50 per cent of Spain. By the end of the month, Adolf Hitler sent the the Nationalists 26 German fighter aircraft. He also sent 30 Junkers 52s from Berlin and Stuttgart to Morocco. Over the next couple of weeks the aircraft transported over 15,000 troops to Spain. By early September, 1936, General Emilio Mola and his troops gained control of San Sebastián. This was an important victory as it cut the Basque communications with France. (49)

On 4th September, 1936, José Giral resigned and was replaced by Francisco Largo Caballero, who brought into his government two left-wing radicals, Angel Galarza (minister of the interior) and Alvarez del Vayo (minister of foreign affairs). He also included four anarchists, Juan Garcia Oliver (Justice), Juan López Sánchez (Commerce), Federica Montseny (Health) and Juan Peiró (Industry) and two right-wing socialists, Juan Negrin (Finance) and Indalecio Prieto (Navy and Air) in his government. Largo Caballero also gave two ministries to the Communist Party (PCE): Jesus Hernández (Education) and Vicente Uribe (Agriculture). The cabinet also included five liberals and it was argued that it was the first genuine Popular Front government. (50)

Joseph Stalin wrote to Largo Caballero warning him of the dangers of having members of the PCE in the government. "The urban petty and middle bourgeoisie must be attracted to the government side... The leaders of the Republican party should not be repulsed; on the contrary they should be drawn in, persuaded to get down to the job in harness with the government. This is necessary in order to prevent the enemies of Spain from presenting it as a Communist Republic, and thus to avert their open intervention, which represents the greatest danger to Republican Spain." (51)

In September 1936, Lieutenant Colonel Walther Warlimont of the German General Staff arrived as the German commander and military adviser to General Francisco Franco. The following month Warlimont suggested that a German Condor Legion should be formed to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The initial force comprised about a hundred aircraft and was supported by anti-aircraft and anti-tank units and four tank companies. The Condor Legion, under the command of General Hugo Sperrle, was an autonomous unit responsible only to Franco. The legion amounted to some 3,800 men at the beginning, later to 5,000. (52)

The Soviet Union were the main suppliers of military aid to the Republican Army. This included 1,000 aircraft, 900 tanks, 1,500 artillery pieces, 300 armoured cars, 15,000 machine-guns, 30,000 automatic firearms, 30,000 mortars, 500,000 riles and 30,000 tons of ammunition. The Soviets expected the Republicans to pay for these military supplies in gold. On the outbreak of the war Spain had the world's fourth largest reserves of gold. During the war approximately $500 million, or two-thirds of Spain's gold reserves, were shipped to the Soviet Union. (53)

The main weakness of the Republic lay in its armed forces. Two-thirds of army officers supported the rebellion. By the 1st November 1936, 25,000 Nationalist troops under General José Enrique Varela had reached the western and southern suburbs of Madrid. This began the siege of Madrid that was to last for nearly three years. Francisco Largo Caballero and his government decided to leave Madrid on 6th November, 1936. This decision was criticized by the four anarchists in his cabinet who regarded leaving the capital as cowardice. At first they refused to go but were eventually persuaded to move to Valencia with the rest of the government. (54)

After the failure of General Franco's attempt to take Madrid, Hitler decided to increase his military support of the Nationalists. "Hitler's real reasons for helping Franco were strategic. A fascist Spain would present a threat to France's rear as well as the British route to the Suez canal. There was even the tempting possibility of U-boat bases on the Atlantic coast. The civil war also served to divert attention away from his central European strategy, while offering an opportunity to train men and to test equipment and tactics." (55)

The Popular Front government controlled most of the major cities and all the main industrial areas including Catalonia, the Basque country and the Asturias. It therefore possessed the heavy industry vital for the production of armaments, although it would be difficult to fully utilise these resources without imports of raw materials. The government held the gold reserves and could in theory purchase arms from abroad. However, many countries under the terms of the Non-Intervention Agreement, refused to sell them weapons. The Nationalists also had the advantage of acquiring most of the food producing areas. (56)

The most important change brought about in Republican held areas was the establishment of collectives in industry and agriculture, owned and controlled by the workforce. This social experiment derived mainly from anarchist ideas. In all, about 2,000 factories and retail businesses were collectivised and about 2,500 agricultural collectives were established. In the first few months of the war, 70 per cent of all enterprises in Barcelona had been collectivised including transport and public utilities, such as electricity. (57)

After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February, 1937. General José Miaja sent the Dimitrov Battalion and the British Battalion to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. According to one source they were told by the political commissar: "We are prepared to sacrifice our lives, because this sacrifice is not only for the peace and freedom of the Spanish people, but also for the peace and freedom of the French people, the Germans, the English, the Italians, the Czechs, the Croats, and for all the peoples of the world." (58)

The following day, at what became known as Suicide Hill, the Republicans suffered heavy casualties. This included the deaths of Walter Grant, Christopher Caudwell, Clem Beckett and William Briskey. Later that day Tom Wintringham sent Jason Gurney to find out what was happening: "I had only gone about 700 yards when I came across one of the most ghastly sights I have ever seen. I found a group of wounded (British) men who had been carried to a non-existent field dressing station and then forgotten. There were about fifty stretchers, but many men had already died and most of the others would be dead by morning. They had appalling wounds, mostly from artillery. One little Jewish kid of about eighteen lay on his back with his bowels exposed from his navel to his genitals and his intestines lying in a ghastly pinkish brown heap, twitching slightly as the flies searched over them. He was perfectly conscious. Another man had nine bullet holes across his chest. I held his hand until it went limp and he was dead. I went from one to the other but was absolutely powerless. Nobody cried out or screamed except they all called for water and I had none to give. I was filled with such horror at their suffering and my inability to help them that I felt I had suffered some permanent injury to my spirit." (59)

Led by Robert Merriman, the 373 members of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion moved into the trenches on 23rd February. When the were ordered over the top they were backed by a pair of tanks from the Soviet Union. On the first day 20 men were killed and nearly 60 were wounded. Colonel Vladimir Copic, the Yugoslav commander of the Fifteenth Brigade, ordered Merriman and his men to attack the Nationalist forces at Jarama. As soon as he left the trenches Merriman was shot in the shoulder, cracking the bone in five places. Of the 263 men who went into action that day, only 150 survived. One soldier remarked afterwards: "The battalion was named after Abraham Lincoln because he, too, was assassinated." (60)

The Battle of Jarma resulted in a stalemate. The Republicans had lost land to the depth of ten miles along a front of some fifteen miles, but had retained the road to Valencia. Both sides claimed a victory but both had really suffered defeats. The International Brigades had 8,000 casualties (1,000 dead and 7,000 wounded) and the Nationalists about 6,000. The volunteers now realised that there would be no quick victory and with the rebels receiving so much help from Italy and Germany, in the long-term, they faced the possibility of defeat. (61)

George Orwell

In 1933 George Orwell published Down and Out in Paris and London. This was followed by three novels, Burmese Days (1934), A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) and Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). The books did not sell well and Orwell was unable to make enough money to become a full-time writer and had to work as a teacher and as an assistant in a bookshop. A committed socialist he also wrote for a variety of left-wing journals.

Orwell had been shocked and dismayed by the persecution of socialists in Nazi Germany. Like most socialists, he had been impressed by the way that the Soviet Union had been unaffected by the Great Depression and did not suffer the unemployment that was being endured by the workers under capitalism. However, Orwell was a great believer in democracy and rejected the type of government imposed by Joseph Stalin.

Orwell decided that he would now concentrate on politics. As he recalled several years later: "In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer... Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows." (62)

Soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he decided, despite only being married for a month, to go and support the Popular Front government against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. He contacted John Strachey who took him to see Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Orwell later recalled: "Pollitt after questioning me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me. He also tried to frighten me out of going by talking a lot about Anarchist terrorism." (63)

Orwell visited the headquarters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and obtained letters of recommendation from Fenner Brockway and Henry Noel Brailsford. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, to run the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an anti-Stalinist organisation formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. As a result of an ILP fundraising campaign in England, the POUM had received almost £10,000, as well as an ambulance and a planeload of medical supplies. (64)

It has been pointed out by D. J. Taylor, that McNair was "initially wary of the tall ex-public school boy with the drawling upper-class accent". (65) McNair later recalled: "At first his accent repelled my Tyneside prejudices... He handed me his two letters, one from Fenner Brockway, the other from H.N. Brailsford, both personal friends of mine. I realised that my visitor was none other than George Orwell, two of whose books I had read and greatly admired." Orwell told McNair: "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism". Orwell told him that he was also interested in writing about the "situation and endeavour to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France." (66) Orwell also talked about producing a couple of articles for The New Statesman. (67)

McNair went to see Orwell at the Lenin Barracks a few days later: "Gone was the drawling ex-Etonian, in his place was an ardent young man of action in complete control of the situation... George was forcing about fifty young, enthusiastic but undisciplined Catalonians to learn the rudiments of military drill. He made them run and jump, taught them to form threes, showed them how to use the only rifle available, an old Mauser, by taking it to pieces and explaining it." (68)

In January 1937 George Orwell, given the rank of corporal, was sent to join the offensive at Aragón. The following month he was moved to Huesca. Orwell wrote to Victor Gollancz about life in Spain. "Owing partly to an accident I joined the POUM militia instead of the International Brigade which was a pity in one way because it meant that I have never seen the Madrid front; on the other hand it has brought me into contact with Spaniards rather than Englishmen and especially with genuine revolutionaries. I hope I shall get a chance to write the truth about what I have seen." (69)

A report appeared in a British newspaper of Orwell leading soldiers into battle: "A Spanish comrade rose and rushed forward. Charge! shouted Blair (Orwell)... In front of the parapet was Eric Blair's tall figure coolly strolling forward through the storm of fire. He leapt at the parapet, then stumbled. Hell, had they got him? No, he was over, closely followed by Gross of Hammersmith, Frankfort of Hackney and Bob Smillie, with the others right after them. The trench had been hastily evacuated... In a corner of a trench was one dead man; in a dugout was another body." (70)

On 10th May, 1937, Orwell was wounded by a Fascist sniper. He told Cyril Connolly "a bullet through the throat which of course ought to have killed me but has merely given me nervous pains in the right arm and robbed me of most of my voice." He added that while in Spain "I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before." (71)

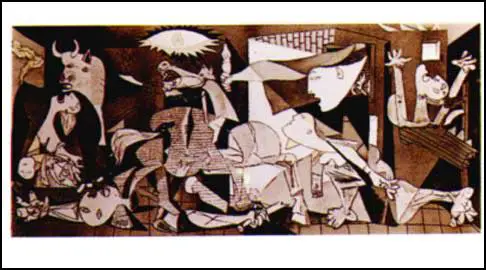

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of POUM, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." (72)

As George Orwell had been fighting with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, George Orwell, John McNair and Stafford Cottman were able to escape to France on 23rd June. (73)

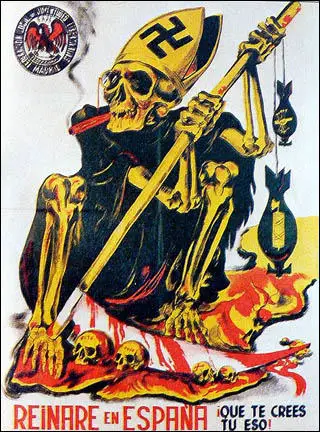

Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. When he arrived back in England he was determined to expose the crimes of Stalin in Spain. However, his left-wing friends in the media, rejected his articles, as they argued it would split and therefore weaken the resistance to fascism in Europe. He was particularly upset by his old friend, Kingsley Martin, the editor of the country's leading socialist journal, The New Statesman, for refusing to publish details of the killing of the anarchists and socialists by the communists in Spain. Left-wing and liberal newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, as well as the right-wing Daily Mail and The Times, joined in the cover-up. (74)

Orwell did managed to persuade the New English Weekly to publish an article on the reporting of the Spanish Civil War. "I honestly doubt, in spite of all those hecatombs of nuns who have been raped and crucified before the eyes of Daily Mail reporters, whether it is the pro-Fascist newspapers that have done the most harm. It is the left-wing papers, the News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, with their far subtler methods of distortion, that have prevented the British public from grasping the real nature of the struggle." (75)

In another article in the magazine he explained how in "Spain... and to some extent in England, anyone professing revolutionary Socialism (i.e. professing the things the Communist Party professed until a few years ago) is under suspicion of being a Trotskyist in the pay of Franco or Hitler... in England, in spite of the intense interest the Spanish war has aroused, there are very few people who have heard of the enormous struggle that is going on behind the Government lines. Of course, this is no accident. There has been a quite deliberate conspiracy to prevent the Spanish situation from being understood." (76)

George Orwell wrote about his experiences of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia. The book was rejected by Victor Gollancz because of its attacks on Joseph Stalin. During this period Gollancz was accused of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). He later admitted that he had come under pressure from the CPGB not to publish certain books in the Left Book Club: "When I got letter after letter to this effect, I had to sit down and deny that I had withdrawn the book because I had been asked to do so by the CP - I had to concoct a cock and bull story... I hated and loathed doing this: I am made in such a way that this kind of falsehood destroys something inside me." (77)

The book was eventually published by Frederick Warburg, who was known to be both anti-fascist and anti-communist, which put him at loggerheads with many intellectuals of the time. The book was attacked by both the left and right-wing press. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years. As Bernard Crick has pointed out: "Its literary merits were hardly noticed... Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style." (78)

Victory for Fascism

General Francisco Franco came under pressure from Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to obtain a quick victory by taking Madrid. He eventually decided to use 30,000 Italians and 20,000 legionnaires to attack Guadalajara, forty miles northeast of the capital. On 8th March the Italian Corps took Guadalajara and began moving rapidly towards Madrid. Four days later the Republican Army with Soviet tanks counter-attacked. The Italians suffered heavy losses and those left alive were forced to retreat on 17th March, 1937. The Republicans also captured documents which proved that the Italians were regular soldiers and not volunteers. However, the Non-Intervention Committee refused to accept the evidence and the Italian government boldly announced that no Italian soldiers would be withdrawn until the Nationalist Army was victorious. (79)

On 19th April 1937, Franco forced the unification of the Falange Española and the Carlists with other small right-wing parties to form the Falange Española Tradicionalista. Franco then had himself appointed as leader of the new organisation. Imitating the tactics of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, giant posters of Franco and José Antonio Primo de Rivera, who had been executed on 20th November, 1936, were displayed along with the slogan, "One State! One Country! One Chief! Franco! Franco! Franco!" all over Spain. (80)

The town of Guernica is situated 30 kilometers east of Bilbao, in the Basque province of Vizcaya. Guernica was considered to be the spiritual capital of the Basque people and had a population of about 7,000 people. On 26th April 1937, Guernica was bombed by the German Condor Legion. As it was a market day the town was crowded. The town was first struck by explosive bombs and then by incendiaries. As people fled from their homes they were machine-gunned by fighter planes. The three hour raid completely destroyed the town. It is estimated that 1,685 people were killed and 900 injured in the attack. (81)

General Francisco Franco denied that he had nothing to do with the raid and claimed that the town had been dynamited and then burnt by Anarchist Brigades. Franco issued a statement after the bombing: "We wish to tell the world, loudly and clearly, a little about the burning of Guernica. It was destroyed by fire and gasoline. The red hordes in the criminal service of Aguirre burnt it to ruins. The fire took place yesterday and Aguirre, since he is a common criminal, has uttered the infamous lie of attributing this atrocity to our noble and heroic air force." (82)

The Spanish church backed this story and its professor of theology in Rome went so far as to declare that "the truth is there is not a single German in Spain. Franco only needs Spanish soldiers which are second to none in the world." After the war a telegram sent from Franco's headquarters was discovered and revealed that he had asked the German Condor Legion to carry out the attack on Guernica. It is believed that the attack was an attempt to demoralize the Basque people. Germany had agreed as they wanted to carry out "a major experiment in the effects of aerial terrorism." (83)

Francisco Largo Caballero came under increasing pressure from the Communist Party (PCE) to promote its members to senior posts in the government. He also refused their demands to suppress the Worker's Party (POUM). In May 1937, the Communists withdrew from the government. In an attempt to maintain a coalition government, President Manuel Azaña sacked Largo Caballero and asked Juan Negrin to form a new cabinet. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history." Negrin now began appointing members of the PCE to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. (84)

Negrin's government set out to limit the revolution and abolish the collectives. It argued that any revolution must be postponed until the war had been won. Revolution was seen as a distraction from the main business of winning the war. "It also threatened to alienate the middle class and peasants. Given the performance of the collectives, the Communists and their supporters had a number of points on their side. But the major reason why they took an anti-revolutionary line was to follow Soviet foreign policy strategy. The USSR wished to forge an alliance with Britain and France in a front against which would alarm and antagonise the western democracies and increase their hostility to the Soviet Union as well as setting them irrevocably against the Republic. The Communists therefore wanted to present the republic as a law-abiding democratic regime which deserved the approval of the western powers." (85)

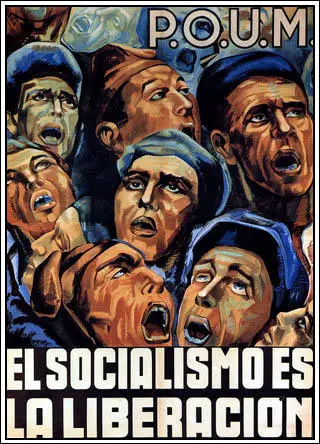

On 16th June, 1937, Negrin ruled that the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) was an illegal organisation. Established by Andres Nin and Joaquin Mauri in 1935, POUM was an revolutionary anti-Stalinist Communist party was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky. The group supported the collectivization of the means of production and agreed with Trotsky's concept of permanent revolution. POUM was very strong in Catalonia. In most areas of Spain it made little impact and in 1935 the organisation was estimated to have only around 8,000 members. (86)

After the Popular Front gained victory POUM supported the government but their radical policies such as nationalization without compensation, were not introduced. During the Spanish Civil War the Workers Party of Marxist Unification grew rapidly and by the end of 1936 it was 30,000 strong with 10,000 in its own militia. Luis Companys attempted to maintain the unity of the coalition of parties in Barcelona. POUM was disliked by the Spanish Communist Party. As Patricia Knight has pointed out: "It did not subscribe to all of Trotsky's views and its best described as a Marxist party which was critical of the Soviet system and particularly of Spain's policies. It was therefore very unpopular with the Communists." (87)

However, after the Soviet consul, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, threatened the suspension of Russian aid, Negrin agreed to sack Andres Nin as minister of justice in December 1936. Nin's followers were also removed from the government. However, as Hugh Thomas has made clear: "The POUM were not Trotskyists, Nin having broken with Trotsky on entering the Catalan government and Trotsky having spoken critically of the POUM. No, what upset the communists was the fact that the POUM were a serious group of revolutionary Spanish Marxists, well-led, and independent of Moscow." (88)

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. On 16th June, Andres Nin and the leaders of POUM were arrested. Also taken into custody were officials of those organisations considered to be under the influence of Trotsky, the National Confederation of Trabajo and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica. (89)

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." Orlov later claimed that "the decision to perform an execution abroad, a rather risky affair, was up to Stalin personally. If he ordered it, a so-called mobile brigade was dispatched to carry it out. It was too dangerous to operate through local agents who might deviate later and start to talk." (90)

Orlov ordered the arrest of Nin. George Orwell explained what happened to Nin in his book, Homage to Catalonia (1938): "On 15 June the police had suddenly arrested Andres Nin in his office, and the same evening had raided the Hotel Falcon and arrested all the people in it, mostly militiamen on leave. The place was converted immediately into a prison, and in a very little while it was filled to the brim with prisoners of all kinds. Next day the P.O.U.M. was declared an illegal organization and all its offices, book-stalls, sanatoria, Red Aid centres and so forth were seized. Meanwhile the police were arresting everyone they could lay hands on who was known to have any connection with the P.O.U.M." (91)

Nin who was tortured for several days. Jesus Hernández, a member of the Communist Party, and Minister of Education in the Popular Front government, later admitted: "Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the dry method. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin resisted the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days his face was a shapeless mass of flesh." Nin was executed on 20th June 1937. (92)

Cecil D. Eby claims that Nin was murdered by "a German hit squad from the International Brigades". The Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party of the United States, reported that "individuals and cells of the enemy had been eliminated like infestations of termites." Eby goes on to argue that the "nearly maniacal purge of putative Trotskyists in the late spring of 1937" displaced the "war against Fascism". (93)

It is believed that Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov originally intended a trial in Spain on the model of the Moscow trials, based on the confessions of people like Nin. This idea was abandoned and instead several anti-Stalinists in Spain died in mysterious circumstances. This included Robert Smillie, the English journalist who was a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Erwin Wolf, ex-secretary of Trotsky, the Austrian socialist Kurt Landau, the journalist, Marc Rhein, the son of Rafael Abramovich, a former leader of the Mensheviks, and José Robles, a Spanish academic who held independent socialist views. (94)

In the Asturias campaign in September 1937, Adolf Galland of the Condor Legion experimented with new bombing tactics. This became known as carpet bombing (dropping all bombs on the enemy from every aircraft at one time for maximum damage). The German airforce was also able to practise the techniques of coordinated ground and air attacks and dive-bombing that became so important during the Second World War. (95)

By the beginning of 1938 the Nationalist Army numbered 600,000, a third larger than the Republican Army. In April General Francisco Franco and his forces reached the sea at Vinaroz, separating Catalonia from Valencia, thereby cutting the remaining Republican zone in two. Juan Negrin believed that the only way the Republic would be saved was if war broke out between Germany and Britain. Franco also feared this and decided to move against Valencia instead of the easier target, Catalonia, for fear of French intervention should the fighting approach their frontier. (96)

On 1st May, 1938, Juan Negrin proposed a thirteen-point peace plan. When this was rejected he ordered an attack across the fast-flowing River Ebro in an attempt to relieve pressure on Valencia. General Juan Modesto, a member of the Communist Party (PCE), was placed in charge of the offensive. Over 80,000 Republican troops, including the 15th International Brigade and the British Battalion, began crossing the river in boats on 25th July. (97)

Tom Murray, from Scotland, was one of the men who took part in the battle. "The crossing of the Ebro at night was a remarkable performance. The pontoons consisted of narrow buoyant sections tied together and men would sit straddled across the junctions of these sections to hold them firm, because the Ebro was a very fast-flowing river. And then others went across in boats. The mules were swum across. We went across the pontoons carrying our weapons, our machine guns. We had light machine guns as well as the heavy ones. We had five machine gun groups in our Company. No two people had to be on one section at the same time. We got across all right, lined up and marched up to the top of the hill." (98)

The men then moved forward towards Corbera and Gandesa. On 26th July the Republican Army attempted to capture Hill 481, a key position at Gandesa. Hill 481 was well protected with barbed wire, trenches and bunkers. The Republicans suffered heavy casualties and after six days was forced to retreat to Hill 666 on the Sierra Pandols. It successfully defended the hill from a Nationalist offensive on 23rd September but once again large numbers were killed, many as a result of air attacks. Bill Feeley later recalled: "I used to watch them (fascist aircraft) bomb, and you could see the bombs come out. They used to drop bombs when they were very high up. We didn't have any real anti-aircraft equipment, only machine guns mostly, because of this Non-Intervention Agreement." (99)

Over a period of 113 days, nearly 250,000 men took part in the battle at Ebro. It is estimated that a total of 13,250 soldiers were killed: Republicans (7,150) and Nationalists (6,100). About another 110,000 suffered wounds or mutilation. These were the worst casualties of the war and it finally destroyed the Republican Army as a fighting force. "Effectively, the Republic was defeated, yet it simply refused to accept the fact. Madrid and Barcelona were swelled with refugees and their populations on the verge of starvation. Negrin again began to search for a possible formula to allow a compromise peace." (100)

On 21st September 1938, Juan Negrin announced at the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. This was not a great sacrifice as there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery. (101)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt produced a plan to end the war. Neville Chamberlain rejected the idea as he did not want to interfere with his negotiations with Adolf Hitler. On 26th January, 1939, Barcelona fell to the Nationalist Army. Members of the Popular Front government now moved to Perelada, close to the French border. With the nationalist forces still advancing, President Manuel Azaña and his colleagues crossed into France. On 27th February, 1939, Chamberlain recognized the Nationalist government headed by General Francisco Franco. Later that day Azaña resigned from office, declaring that the war was lost and that he did not want Spaniards to make anymore useless sacrifices. (102)

Available information suggests that there were about 500,000 deaths from all causes during the Spanish Civil War. An estimated 200,000 died from combat-related causes. Of these, 110,000 fought for the Republicans and 90,000 for the Nationalists. This implies that 10 per cent of all soldiers who fought in the war were killed. It has been calculated that the Nationalist Army executed 75,000 people in the war whereas the Republican Army accounted for 55,000. These deaths takes into account the murders of members of rival political groups. (103)

It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. (104)

The economic blockade of Republican controlled areas caused malnutrition in the civilian population. It is believed that this caused the deaths of around 25,000 people. All told, about 3.3 per cent of the Spanish population died during the war with another 7.5 per cent being injured. After the war it is believed that the government of General Franco arranged the executions of 100,000 Republican prisoners. It is estimated that another 35,000 Republicans died in concentration camps in the years that followed the war. (105)

Primary Sources

(1) Salvador de Madariaga, a member of the Republican Union Party, commented on the clash between Francisco Largo Caballero and Indalecio Prieto.

What made the Spanish Civil War inevitable was the civil war within the Socialist party. No wonder Fascism grew. Let no one argue that it was fascist violence that developed socialist violence. It was not at the Fascists that Largo Caballero's gunmen shot but at their brother socialists. It was (Largo Caballero's) avowed, nay, his proclaimed policy to rush Spain on to the dictatorship of the proletariat. Thus pushed on the road to violence, the nation, always prone to it, became more violent than ever. This suited the fascists admirably, for they are nothing if not lovers and adepts of violence.

(2) Claude Cockburn, Reporter in Spain (1936)

On 12th July 1936 gunmen in a touring car nosed slowly through sparse traffic under the arc lamps of a Madrid street, opened fire with a sub-machine-gun at the defenceless back of a man standing chatting on his doorstep, and roared off among the tram-lines, leaving him dying in a puddle of his young blood on the pavement.

That in a manner of speaking was the Sarajevo of the Spanish war. The young man they killed was Jose Castillo, Lieutenant of Assault Guards. I never saw Castillo, but afterwards I heard all sorts of people speak of him with a kind of urgency and heartbreak, as though it were impossible that you too should not have known, and therefore loved, so fine a young man.

In a corps which in the five years of its existence had already acquired a high military reputation, Castillo was already distinguished, and already loved, by men who are not very easy pleased nor easy fooled.

In the working-class districts of Madrid he was equally well known and liked. He was declared a gallant and patriotic young officer, as dauntless a defender of the Republic as you could wish to see, and a man - as a Madrid workman said to me afterwards - "who made the culture and the progress we were after seem more real to us".

(3) Francisco Franco, speech (17th July 1936)

Spaniards! The nation calls to her defense all those of you who hear the holy name of Spain, those in the ranks of the Army and Navy who have made a profession of faith in the service of the Motherland, all those who swore to defend her to the death against her enemies. The situation in Spain grows more critical every day; anarchy reigns in most of the countryside and towns; government-appointed authorities encourage revolts, when they do not actually lead them; murderers use pistols and machine guns to settle their differences and to treacherously assassinate innocent people, while the public authorities fail to impose law and order. Revolutionary strikes of all kinds paralyze the life of the nation, destroying its sources of wealth and creating hunger, forcing working men to the point of desperation. The most savage attacks are made upon national monuments and artistic treasures by revolutionary hordes who obey the orders of foreign governments, with the complicity and negligence of local authorities. The most serious crimes are committed in the cities and countryside, while the forces that should defend public order remain in their barracks, bound by blind obedience to those governing authorities that are intent on dishonoring them. The Army, Navy, and other armed forces are the target of the most obscene and slanderous attacks, which are carried out by the very people who should be protecting their prestige. Meanwhile, martial law is imposed to gag the nation, to hide what is happening in its towns and cities, and to imprison alleged political opponents.

(4) Mikhail Koltzov, the Soviet journalist, recorded the evacuation of Madrid by the Popular Front government on 6th November 1936.

I made my way to the War Ministry, to the Commissariat of War. Hardly anyone was there. I went to the offices of the Prime Minister. The building was locked. I went to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was deserted. In the Foreign Press Censorship an official told me that the government, two hours earlier, had recognized that the situation of Madrid was hopeless and had already left. Largo Caballero had forbidden the publication of any news about the evacuation "in order to avoid panic". I went to the Ministry of the Interior. The building was nearly empty. I went to the central committee of the Communist Party. A plenary meeting of the Politburo was being held. They told me that this very day Largo Caballero had suddenly decided to evacuate. His decision had been approved by the majority of the cabinet. The Communist ministers wanted to remain, but it was made clear to them that such a step would discredit the government and that they were obliged to leave like all the others. Not even the most prominent leaders of the various organizations, nor the departments and agencies of the state, had been informed of the government's departure. Only at the last moment had the Minister told the Chief of the Central General Staff that the government was leaving. The Minister of the Interior, Galarza, and his aide, the Director of Security Munoz, had left the capital before anyone else. The staff of General Pozas, the commander of the central front, had scurried off. Once again I went to the War Ministry. I climbed the stairs to the lobby. Not a soul! On the landing two old employees are seated like wax figures wearing livery and neatly shaven waiting to be called by the Minister at the sound of his bell! It would be just the same if the Minister were the previous one or a new one. Rows of offices! All the doors are wide open. I enter the War Minister's office. Not a soul! Further down, a row of offices - the Central General Staff, with its sections; the General Staff with its sections; the General Staff of the Central Front, with its sections; the Quartermaster Corps with its sections; the Personnel Department, with its sections. All the doors are wide open. The ceiling lamps shine brightly. On the desks there are abandoned maps, documents communiqués, pencils, pads filled with notes. Not a soul!

(5) Jack Jones went to fight in the Spanish Civil War in 1937. He wrote about his experiences in the International Brigade in his autobiography, Union Man (1986)

The focal point for the mobilization of the International Brigades was in Paris; understandably so, because underground activities against Fascism had been concentrated there for some years. I led a group of volunteers to the headquarters there, proceeding with the greatest caution because of the laws against recruitment in foreign armies and the non-intervention policies of both Britain and France. From London onwards it was a clandestine operation until we arrived on Spanish soil.

While in Paris we were housed in workers' homes in one of the poorest quarters of the city. But it wasn't long before we were on our way, by train, to a town near the Pyrenees. From there we travelled by coach to a rambling old farmhouse in the foothills of the Pyrenees. After a rough country meal in a barn we met our guide who led us through the mountain passes into Spain.

In the light of the morning we could see Spanish territory. After five hours or so, stumbling down the mountainside (I found it almost as hard going down as climbing up), we came to an outpost and from there were taken by truck to a fortress at Figueras. This was a reception centre for the volunteers. The atmosphere of old Spain was very apparent in the ancient castle. For the first day or so we felt exhausted after the long climb. The food was pretty awful. We ate it because we were hungry but without relish.

For some the first lessons about the use of a rifle were given before we moved off to the base. I at least could dismantle and assemble a rifle bolt and knew something about firing and the care of a weapon. But my first shock came when I was told of the shortage of weapons and the fact that the rifles (let alone other weapons) were in many cases antiquated and inaccurate.

Training at the base was quick, elementary but effective. For me life was hectic, meeting good companions and experiencing a genuine international atmosphere. There were no conscripts or paid mercenaries. I got to know a German Jew who had escaped the clutches of Hitler's hordes and was then a captain in the XII Brigade. He had hopes of going on ultimately to Palestine and striving for a free state of Israel. He was not only a good soldier but a brave one too. That was also true of a smart young Mexican whom I met. He had been an officer in the Mexican Army and was a member of the National Revolutionary Party of his country.

(6) Bill Bailey wrote to his mother explaining why he was fighting in the Spanish Civil War (1937)

You see Mom, there are things that one must do in this life that are a little more than just living. In Spain there are thousands of mothers like yourself who never had a fair shake in life. They got together and elected a government that really gave meaning to their life. But a bunch of bullies decided to crush this wonderful thing. That's why I went to Spain, Mom, to help these poor people win this battle, then one day it would be easier for you and the mothers of the future. Don't let anyone mislead you by telling you that all this had something to do with Communism. The Hitlers and Mussolinis of this world are killing Spanish people who don't know the difference between Communism and rheumatism. And it's not to set up some Communist government either. The only thing the Communists did here was show the people how to fight and try to win what is rightfully theirs.

(7) Bill Alexander, Memorials of the Spanish Civil War (1996)

Around 2,400 volunteered from the British Isles and the then British Empire. There can be no exact figure because the Conservative Government, in its support for the Nonintervention Agreement, threatened to use the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1875 which they declared made volunteering illegal. Keeping records and lists of names was dangerous and difficult. However, no-passport weekend trips to Paris provided a way round for all who left these shores en route for Spain. In France active support from French people opened the paths over the Pyrenees.

The British volunteers came from all walks of life, all parts of the British Isles and the then British Empire. The great majority were from the industrial areas, especially those of heavy industry They were accustomed to the discipline associated with working in factories and pits. They learnt from the organization, democracy and solidarity of trade unionism.

Intellectuals, academics, writers and poets were an important force in the early groups of volunteers. They had the means to get to Spain and were accustomed to travelling, whereas very few workers had left British shores. They went because of their growing alienation from a society that had failed miserably to meet the needs of so many people and because of their deep repugnance at the burning of books in Nazi Germany, the persecution of individuals, the glorification of war and the whole philosophy of fascism.

The International Brigades and the British volunteers were, numerically, only a small part of the Republican forces, but nearly all had accepted the need for organization and order in civilian life. Many already knew how to lead in the trade unions, demonstrations and people's organizations, the need to set an example and lead from the front if necessary They were united in their aims and prepared to fight for them. The International Brigades provided a shock force while the Republic trained and organized an army from an assemblage of individuals. The Spanish people knew they were not fighting alone.

(8) Peter Kemp, a graduate of Cambridge University, joined the Carlists during the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his experiences in his book, Mine Were of Trouble (1957)

I was ordered to report to Cancela. I found him talking with some legionaries who had brought in a deserter from the International Brigades - an Irishman from Belfast; he had given himself up to one of our patrols down by the river. Cancela wanted me to interrogate him. The man explained that he had been a seaman on a British ship trading to Valencia, where he had got very drunk one night, missed his ship and been picked up by the police. The next thing he knew, he was in Albacete, impressed into the International Brigades. He knew that if he tried to escape in Republican Spain he would certainly be retaken and shot; and so he had bided his time until he reached the front, when he had taken the first opportunity to desert. He had been wandering around for two days before he found our patrol.

I was not absolutely sure that he was telling the truth; but I knew that if I seemed to doubt his story he would be shot, and I was resolved to do everything in my power to save his life. Translating his account to Cancela, I urged that this was indeed a special case; the man was a deserter, not a prisoner, and we should be unwise as well as unjust to shoot him. Moved either by my arguments, or by consideration for my feelings. Cancela agreed to spare him, subject to de Mora's consent; I had better go and see de Mora at once while Cancela would see that the deserter had something to eat.

De Mora was sympathetic. "You seem to have a good case," he said. "Unfortunately my orders from Colonel Penaredonda are to shoot all foreigners. If you can get his consent I'll be delighted to let the man off. You'll find the Colonel over there, on the highest of those hills. Take the prisoner with you, in case there are any questions, and your two runners as escort.'

It was an exhausting walk of nearly a mile with the midday sun blazing on our backs. "Does it get any hotter in this country?" the deserter asked as we panted up the steep sides of a ravine, the sweat pouring down our faces and backs.

"You haven't seen the half of it yet. Wait another three months," I answered, wondering grimly whether I should be able to win him even another three hours of life.

I found Colonel Penaredonda sitting cross-legged with a plate of fried eggs on his knee. He greeted me amiably enough as I stepped forward and saluted; I had taken care to leave the prisoner well out of earshot. I repeated his story, adding my own plea at the end, as I had with Cancela and de Mora. "I have the fellow here, sir," I concluded, "in case you wish to ask him any questions." The Colonel did not look up from his plate: "No, Peter," he said casually, his mouth full of egg, "I don't want to ask him anything. Just take him away and shoot him.'

I was so astonished that my mouth dropped open; my heart seemed to stop beating. Penaredonda looked up, his eyes full of hatred:

"Get out!" he snarled. "You heard what I said." As I withdrew he shouted after me: "I warn you, I intend to see that this order is carried out."

Motioning the prisoner and escort to follow, I started down the hill; I would not walk with them, for I knew that he would question me and I could not bring myself to speak. I decided not to tell him until the last possible moment, so that at least he might be spared the agony of waiting. I even thought of telling him to try to make a break for it while I distracted the escorts' attention; then I remembered Penaredonda's parting words and, looking back, saw a pair of legionaries following us at a distance. I was so numb with misery and anger that I didn't notice where I was going until I found myself in front of de Mora once more. When I told him the news he bit his lip: