Britain and the Spanish Civil War

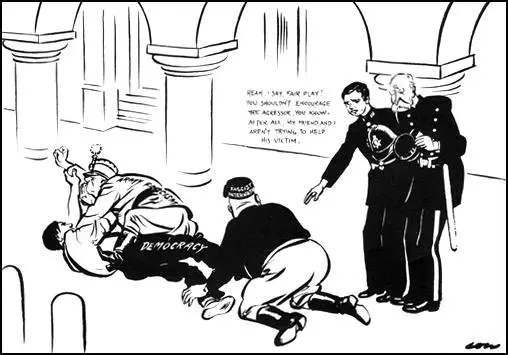

In 1936 the Conservative government feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government.

Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Stanley Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Clement Attlee, Philip Noel-Baker and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be."

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, an organization that had been set-up by the Socialist Medical Association and other progressive groups, was formed. Members included Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Harry Pollitt, Hugh O'Donnell, Mary Redfern Davies and Isobel Brown. Soon afterwards Loutit was appointed Administrator of the Field Unit that was to be sent to Spain. According to Tom Buchanan, the author of Britain and the Spanish Civil War (1997), "he disregarded a threat of disinheritance from his father to volunteer."

Stanley Baldwin and Leon Blum now called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. In September 1936 a Non-Intervention Agreement was drawn-up and signed by 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and Italy.

Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Nonintervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship in the Nationalists' fleet.

On 28th November the Italian government signed a secret treaty with the Spanish Nationalists. In return for military aid, the Nationalist agreed to allow Italy to establish bases in Spain in the case of a conflict with France. Over the next three months Mussolini sent to Spain 130 aircraft, 2,500 tons of bombs, 500 cannons, 700 mortars, 12,000 machine-guns, 50 whippet tanks and 3,800 motor vehicles.

Adolf Hitler also continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces but attempted to disguise this by sending the men, planes, tanks, and munitions via Portugal. He also gave permission for the formation of the Condor Legion. The initial force consisted a Bomber Group of three squadrons of Ju-52 bombers; a Fighter Group with three squadrons of He-51 fighters; a Reconnaissance Group with two squadrons of He-99 and He-70 reconnaissance bombers; and a Seaplane Squadron of He-59 and He-60 floatplanes.

The Condor Legion, under the command of General Hugo Sperrle, was an autonomous unit responsible only to Franco. The legion would eventually total nearly 12,000 men. Sperrle demanded higher performance aircraft from Germany and he eventually received the Heinkel He111, Junkers Stuka and the Messerschmitt Bf109. It participated in all the major engagements including Brunete, Teruel, Aragon and Ebro.

The Labour Party originally supported the government's non-intervention policy. However, when it became clear that Hitler and Mussolini were determined to help the Nationalists win the war, Labour leaders began to call for Britain to supply the Popular Front with military aid. Some members of the party joined the International Brigades and fought for the Republicans in Spain.

A. J. Ayer pointed out in his autobiography, Part of My Life (1977): "What awakened me to politics was not the menace of Hitler or the plight of the unemployed in England, for all that I sympathized with the hunger marchers, but the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. This was an issue which I saw entirely in black and white. Franco was a military adventurer employing Moorish, Italian and German troops to massacre his own countrymen in the interest of rapacious landlords allied with a bigoted and reactionary church. The Republican Government against which he was in rebellion was the legitimate government of Spain: its supporters were fighting not only for their freedom but for a new and better social order. The I fact that the anarchists, initially much more numerous than the i communists, played such a conspicuous part in the Spanish working class movement increased my sympathy for it."

The first British volunteer to be killed was Felicia Browne who died in Aragón on 25th August 1936, during an attempt to blow up a rebel munition train. Of the 2,000 British citizens who served with the Republican Army, the majority were members of the Communist Party. Although some notable literary figures volunteered (W. H. Auden, George Orwell, John Cornford, Stephen Spender, Christopher Caudwell), most of the men who went to Spain were from the working-class, including a large number of unemployed miners.

To stop volunteers fighting for the Republicans, the British government announced on 9th January, 1937, that it intended to invoke the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1870. It also passed the Merchant Shipping (Carriage of Munitions to Spain) Act.

When Neville Chamberlain replaced Stanley Baldwin as prime minister he continued the policy of nonintervention At the end of 1937 he took the controversial decision to send Sir Robert Hodgson to Burgos to be the British government's link with the Nationalist government.

On 18th January 1938, a letter was sent to The Manchester Guardian that was signed by Duchess of Atholl, John Haldane, George Strauss, Elizabeth Wilkinson, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Eileen Power, Richard Acland, Vernon Bartlett, Richard Stafford Cripps, Josiah Wedgwood, Victor Gollancz, Kingsley Martin, Violet Bonham Carter andR. H. Tawney. They argued: "It has now become clear that the Republicans are facing an overwhelming weight of arms, troops, and munitions accumulated by Italy and Germany in flagrant and open violation of their undertakings under the Non-Intervention Agreement...The embargoes must be lifted and the frontiers opened by Britain and France forthwith."

On 13th March 1938 Leon Blum returned to office in France. When he began to argue for an end to the country's nonintervention policy, Chamberlain and the Foreign Office joined with the right-wing press in France and political figures such as Henri-Philippe Petain and Maurice Gamelin to bring him down. On 10th April 1938, Blum was replaced by Edouard Daladier, a politician who agreed not only with Chamberlain's Spanish strategy but his appeasement policy.

It has been claimed that the British secret service was involved in the military rebellion in Madrid by Segismundo Casado. Soon afterwards, on 27th February 1939, the British government recognized General Francisco Franco as the new ruler of Spain.

Primary Sources

(1) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

When the Spanish Republican Government was formed in 1936 the news was received enthusiastically by Socialists in Britain. Many of the new Government members were well known in the international Socialist movement. The emergence of a democratic regime in Spain was a bright light in a gloomy period when war had raped Abyssinia, and Germany had repudiated the Locarno Treaty. On the sudden outbreak of civil war in July, 1936, Socialist movements in all those European countries where they were allowed to exist immediately took steps to consider whether intervention should be demanded.

The Fascist attack was regarded as aggression by the majority of thinking people. Leon Blum, at the time Prime Minister of France, was greatly concerned in this matter. As political head of a nation which was bordered by Spain he had to consider the danger of some of the belligerents being forced over the border; as a Socialist he had a duty to go to the help of his comrades, members of a legally elected Government, who had been attacked by men organized and financed from outside Spanish home territory.

In Britain, although the Government was against intervention, the Labour Party had to face the strong demands from the rank-and-file for concrete action. The three executives met at Transport House to consider the next move, and I was present as a member of the Parliamentary Executive. We were largely influenced by Blum's policy. He had decided that he could not risk committing his country to intervention. Germany and Italy were supplying arms, aircraft, and men to the Spanish Fascists, and Blum considered that any action on the Franco-Spanish border on behalf of the Republican Government would bring imminent danger of retaliatory moves by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany on France's eastern flank. As a result of this French attitude Herbert Morrison's appeal in favour of intervention received little support. Although, like him, I was inclined towards action I pointed out that if France failed to intervene it would be a futile gesture to advise that Britain should do so. We had the recent farce of sanctions against Italy as a warning.

(2) A. J. Ayer, Part of My Life (1977)

What awakened me to politics was not the menace of Hitler or the plight of the unemployed in England, for all that I sympathized with the hunger marchers, but the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. This was an issue which I saw entirely in black and white. Franco was a military adventurer employing Moorish, Italian and German troops to massacre his own countrymen in the interest of rapacious landlords allied with a bigoted and reactionary church. The Republican Government against which he was in rebellion was the legitimate government of Spain: its supporters were fighting not only for their freedom but for a new and better social order. The I fact that the anarchists, initially much more numerous than the i communists, played such a conspicuous part in the Spanish working class movement increased my sympathy for it. Of course I now know that the facts were not quite so simple. The government had been weak; the anarchists had fomented disorder; there was terrorism on both sides; when the dependence of the Republican cause on the supply of arms from Russia and the help of the International Brigades brought the communists to power, they exercised it ruthlessly. Nevertheless, it remains true that Franco's rule was tyrannical, that he could not have won without foreign help, that the assistance which he received from the Italians and the Germans in men and material came earlier and remained far greater than that which the Government received from Russia, and that the timid and hypocritical policy of non-intervention pursued by the French and British Governments, denying the Spanish Government their right to purchase arms, told heavily in Franco's favour. The hatred which I then felt for Neville Chamberlain and his acolytes, mainly on account of their appeasement of Hitler and Mussolini but also because of their strictly business-like attitude to domestic problems, has never left me, and I still find it difficult to view the Conservative party in any other light.

(3) Bill Alexander, Memorials of the Spanish Civil War (1996)

Around 2,400 volunteered from the British Isles and the then British Empire. There can be no exact figure because the Conservative Government, in its support for the Nonintervention Agreement, threatened to use the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1875 which they declared made volunteering illegal. Keeping records and lists of names was dangerous and difficult. However, no-passport weekend trips to Paris provided a way round for all who left these shores en route for Spain. In France active support from French people opened the paths over the Pyrenees.

The British volunteers came from all walks of life, all parts of the British Isles and the then British Empire. The great majority were from the industrial areas, especially those of heavy industry They were accustomed to the discipline associated with working in factories and pits. They learnt from the organization, democracy and solidarity of trade unionism.

Intellectuals, academics, writers and poets were an important force in the early groups of volunteers. They had the means to get to Spain and were accustomed to travelling, whereas very few workers had left British shores. They went because of their growing alienation from a society that had failed miserably to meet the needs of so many people and because of their deep repugnance at the burning of books in Nazi Germany, the persecution of individuals, the glorification of war and the whole philosophy of fascism.

The International Brigades and the British volunteers were, numerically, only a small part of the Republican forces, but nearly all had accepted the need for organization and order in civilian life. Many already knew how to lead in the trade unions, demonstrations and people's organizations, the need to set an example and lead from the front if necessary They were united in their aims and prepared to fight for them. The International Brigades provided a shock force while the Republic trained and organized an army from an assemblage of individuals. The Spanish people knew they were not fighting alone.

(4) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Those who ensured that defeat were not even in Spain, nor indeed in Germany nor Italy. The responsibility was in France and in Britain, where the maintenance of unilateral non-intervention ushered in Franco, Petain and the war, with all its millions of deaths. My personal background did not place me in the left-wing avant-garde, nor was it ever the habit in our family to be apologetic about our actions. Therefore during my brief London stopover I stayed in the Junior Constitutional Club, which then faced Green Park half way down Piccadilly. The Conservative Party was the dominant political influence amongst its members but, though everyone knew I was in Spain, no one tried to make me in any way uncomfortable. Indeed it was clear that a considerable current of sympathy existed in that Club for the Spanish Government and, without my asking, I was given several substantial cheques for Spanish Medical Aid. I remember noting that this interest came more typically from ex-service and country members. I continued my membership of the Club until the Munich. Agreement when I resigned in disgust at Chamberlain's conduct.

That opinion in our country was becoming more and more favourable towards the Spanish Government was strikingly evident during that short London stay at the end of November 1936. By 1938 the Gallup poll showed that 57% of the British were pro-Republic and only 7% positively pro-Franco. In January 1939, it had become 72% for the Republic.

(5) Bernard Knox, Premature Anti-Fascist (1998)

In September I received a letter from my friend John Cornford, the leader of the Communist movement in Cambridge, who had just returned from Spain, where he had fought for a few weeks on the Aragon front, in a column organized by the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, the POUM, a party that was later to be suppressed as too revolutionary. He had returned to England to recruit a small British unit that would set an example of training and discipline (and shaving) to the anarchistic militias operating out of Barcelona. He asked me to join and I did so without a second thought.

I knew no more about Spanish politics and history than most of my fellow-countrymen, that is to say, not much. I had read (in translation) much (but not all) of Don Quixote, and seen reproductions of the great paintings of Velázquez and Goya. I knew that Philip II had married an English reigning Queen - Mary - and on her death claimed the throne of England, but had been defeated when in 1588 he sent the great Armada to invade England and enforce his claim. I knew that the Duke of Wellington had fought a long, hard campaign against Napoleonic armies in Portugal and Spain and that guerrilla (which was to become my military specialty in World War II) was a Spanish word. But I had no real understanding of the complicated situation that had produced the military revolt of July 1936. What I did know was that Franco had the full support of Hitler and Mussolini. In fact, that support had been decisive at the beginning of the war. The military coup had failed in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain's principal cities. Franco's best troops, the Foreign Legion and the Regulares, the Moorish mercenaries recruited to fight against their own people, were cooped up in Morocco, since the Spanish Navy had declared for the Republic. Planes and pilots from the Luftwaffe and the Italian Air Force, in the first military airlift in history, had flown some 8,000 troops across to Sevilla, Franco's base for the advance on Madrid.

And this was all I needed to make up my mind. I left a few days later for Paris, with a group of a dozen or so volunteers that John had assembled. There were three Cambridge graduates and one from Oxford (a statistic I have always been proud of), as well as one from London University. There was a German refugee artist who had been living in London, two veterans of the British Army and one of the Navy, an actor, a proletarian novelist and two unemployed workmen. Before we left, I had gone with John to visit his father in Cambridge; he was the distinguished Greek scholar Francis MacDonald Cornford, author of brilliant books on Attic comedy, Thucydides and Greek philosophy, and Plato. He had served as an officer in the Great War and still had the pistol he had had to buy when he equipped himself for France. He gave it to John, and I had to smuggle it through French Customs at Dieppe, for John's passport showed entry and exit stamps from Port-Bou and his bags were likely to be given a thorough going-over.

(6) Tom Buchanan, The Spanish Civil War and the British Labour Movement (1991)

When this information was discussed by the British Labour Movement Conference on the same afternoon there was general support for the continuation of Non-Intervention so long as it could be made more effective. This was the attitude of Attlee, Grenfell and Noel-Baker, another leading critic at Edinburgh, who argued that Non-Intervention was "the right policy provided it was equally applied". Citrine said that there was no alternative to Non-Intervention that could "really materialise for the benefit of the Spanish people". He perceived the question of `volunteers' as one area where Non-Intervention had not been applied and had worked, at least in numerical terms, against the Spanish government. Finally, he believed that they should not create the false impression at the conference that they had the potential to supply British arms to Spain - under no circumstances could they "get the people of this country to go to war about Spain". Therefore, all of their efforts should concentrate on making Non-Intervention "as complete and strong as possible". Bevin continued in this vein, arguing that they had to tell the Spanish "the truth about our position here and (tell them) their only salvation was to get absolute unity to face Franco in Spain". He also suggested that the Labour Party should concentrate its future attacks on the German threat to British financial interests in the Rio Tinto mines. He concluded with a four-point programme which was duly accepted as British policy for the conference.

(7) William Gallacher, The Chosen Few (1940).

Around Easter, 1937, I paid a visit to Spain to see the lads of the British Battalion of the International Brigade. Going up the hillside towards the trenches with Fred Copeman, we could occasionally hear the dull boom of a trench mortar, but more often the eerie whistle of a rifle bullet overhead. Always I felt inclined to get my head down in my shoulders. "I don't like that sound," I said by way of an apology.

"It's all right, Willie, as long as you can hear them,"

I was told. "It's the ones you can't hear that do the damage."

We got into the trenches and I passed along chatting to the boys in the line. From the British we passed into the Spanish trenches and gave the lads there the peoples' front salute. Then, after visiting the American section, we came back to our own lads. All of them came outside and formed a semicircle, and there, with as my background the graves of the boys who had fallen, I made a short speech. It was good to speak under such circumstances, but it was the hardest task I have ever undertaken. When I finished we sang the Internationale with a spirit that all the murderous savagery of fascism can never kill.

The following morning I went into the breakfast room of the Hotel in Madrid to see Herbert Gline, an American working in the Madrid radio station, about a broadcast to America from the Lincoln Battalion. When I got in who should be sitting there but Ellen Wilkinson, Eleanor Rathbone and the Duchess of Atholl. We had a very friendly chat, and I was fortunate in getting their company part of the way home. But whether in Madrid while the shells were falling or in face of the many difficulties that were inseparable from travelling in a country racked with invasion and war, those three women gave an example of courage and endurance that was beyond all praise.

(8) Resolution passed by the British Battalion on 27th March 1937.

We the members of the British working class in the British Battalion of the International Brigade now fighting in Spain in defence of democracy, protest against statements appearing in certain British papers to the effect that there is little or no interference in the civil war in Spain by foreign Fascist Powers.

We have seen with our own eyes frightful slaughter of men, women, and children in Spain. We have witnessed the destruction of many of its towns and villages. We have seen whole areas which have been devastated. And we know beyond a shadow of doubt that these frightful deeds have been done mainly by German and Italian nationals, using German and Italian aeroplanes, tanks, bombs, shells, and guns.

We ourselves have been in action repeatedly against thousands of German and Italian troops, and have lost many splendid and heroic comrades in these battles.

We protest against this disgraceful and unjustifiable invasion of Spain by Fascist Germany and Italy; an invasion in our opinion only made possible by the pro-Franco policy of the Baldwin Government in Britain. We believe that all lovers of freedom and democracy in Britain should now unite in a sustained effort to put an end to this invasion of Spain and to force the Baldwin Government to give to the people of Spain and their legal Government the right to buy arms in Britain to defend their freedom and democracy against Fascist barbarianism. We therefore call upon the General Council of the T.U.C. and the National Executive Committee of the Labour party to organise a great united campaign in Britain for the achievement of the above objects.

We denounce the attempts being made in Britain by the Fascist elements to make people believe that we British and other volunteers fighting on behalf of Spanish democracy are no different from the scores of thousands of conscript troops sent into Spain by Hitler and Mussolini. There can be no comparison between free volunteers and these conscript armies of Germany and Italy in Spain.

Finally, we desire it to be known in Britain that we came here of our own free will after full consideration of all that this step involved. We came to Spain not for money, but solely to assist the heroic Spanish people to defend their country's freedom and democracy. We were not gulled into coming to Spain by promises of big money. We never even asked for money when we volunteered. We are perfectly satisfied with our treatment by the Spanish Government; and we still are proud to be fighting for the cause of freedom in Spain. Any statements to the contrary are foul lies.

(9) The British government was involved in the attempt to being down the government led by B. In April 1938, Sir Orme Sargent, assistant undersecretary of state, wrote to the British Ambassador, Sir Eric Phipps, about this matter.

You may very well properly be shocked at the suggestion that we, or rather you, should do anything which might embarrass or weaken a French Government, even if it be in the hopes that it will, as a result, be replaced by a government more adequate to the critical situation with which we are faced.

(10) Emanuel Shinwell initially argued that the British government should give support to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his visit to Spain in his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

While the war was at its height several of us were invited to visit Spain to see how things were going with the Republican Army. The fiery little Ellen Wilkinson met us in Paris, and was full of excitement and assurance that the Government would win. Included in the party were Jack Lawson, George Strauss, Aneurin Bevan, Sydney Silverman, and Hannen Swaffer. We went by train to the border at Perpignan, and thence by car to Barcelona where Bevan left for another part of the front.

We travelled to Madrid - a distance of three hundred miles over the sierras - by night for security reasons as the road passed through hostile or doubtful territory. It was winter-time and snowing hard. Although our car had skid chains we had many anxious moments before we arrived in the capital just after dawn. The capital was suffering badly from war wounds. The University City had been almost destroyed by shell fire during the earlier and most bitter fighting of the war.

We walked along the miles of trenches which surrounded the city. At the end of the communicating trenches came the actual defence lines, dug within a few feet of the enemy's trenches. We could hear the conversation of the Fascist troops crouching down in their trench across the narrow street. Desultory firing continued everywhere, with snipers on both sides trying to pick off the enemy as he crossed exposed areas. We had little need to obey the orders to duck when we had to traverse the same areas. At night the Fascist artillery would open up, and what with the physical effects of the food and the expectation of a shell exploding in the bedroom I did not find my nights in Madrid particularly pleasant.

It is sad and tragic to realize that most of the splendid men and women, fighting so obstinately in a hopeless battle, whom we met have since been executed, killed in action - or still linger in prison and in exile. The reason for the defeat of the Spanish Government was not in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people. They had a few brief weeks of democracy with a glimpse of all that it might mean for the country they loved. The disaster came because the Great Powers of the West preferred to see in Spain a dictatorial Government of the right rather than a legally elected body chosen by the people. The Spanish War encouraged the Nazis both politically and as a proof of the efficiency of their newly devised methods of waging war. In the blitzkrieg of Guernica and the victory by the well-armed Fascists over the helpless People's Army were sown the seeds for a still greater Nazi experiment which began when German armies swooped into Poland on 1st September, 1939.

It has been said that the Spanish Civil War was in any event an experimental battle between Communist Russia and Nazi Germany. My own careful observations suggest that the Soviet Union gave no help of any real value to the Republicans. They had observers there and were eager enough to study the Nazi methods. But they had no intention of helping a Government which, was controlled by Socialists and Liberals. If Hitler and Mussolini fought in the arena of Spain as a try-out for world war Stalin remained in the audience. The former were brutal; the latter was callous. Unfortunately the latter charge must also be laid at the feet of the capitalist countries as well.

(11) Luis Bolin, Spain, the Vital Years (1967)

In 1936-9 Great Britain and other European and American countries were beginning to think in terms of the coming world conflict. The fact that Hitler and Mussolini helped the Spanish Nationalists was a cause of great and perhaps natural prejudice in those countries, though it should be noted that those who criticized us for accepting Hitler's help saw nothing strange in the acceptance of Stalin, who had invaded Poland with Hitler, as their ally in World War II. When men are fighting for all that is dear to them they accept help from wherever it comes. But the loose habit of referring to all authoritarian regimes other than the Communist as 'Fascist' made it hard for people to appreciate the vast differences that separate the Spanish Falange from Nazism.

(12) Clement Attlee, statement in the House of Commons on the British government's decision to recognize General Franco's government (27th February, 1939)

We see in the action a gross betrayal of democracy, the consummation of two and a half years of the hypocritical pretence of nonintervention and a connivance all the time at aggression. And this is only one step further in the downward march of His Majesty's government in which at every stage they do not sell, but give away, the permanent interest of this country. They do not do anything to build up peace or stop war, but merely announce to the whole world that anyone who is out to use force can always be sure that he will have a friend in the British Prime Minister.

(13) Letter to the The Manchester Guardian signed by Duchess of Atholl, John Haldane, George Strauss, Elizabeth Wilkinson, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Eileen Power, Richard Acland, Vernon Bartlett, Richard Stafford Cripps, Josiah Wedgwood, Victor Gollancz, Kingsley Martin, Violet Bonham Carter and R. H. Tawney (18th January 1938)

The Spanish struggle has entered a critical phase, the democratic Government of Spain has mobilised every man and woman to stem the last desperate offensive of the enemy against Catalonia. The determination of the Spanish people to resist is as great as ever, and its troops are successfully counter-attacking in the south.

It has now become clear that the Republicans are facing an overwhelming weight of arms, troops, and munitions accumulated by Italy and Germany in flagrant and open violation of their undertakings under the Non-Intervention Agreement. At least five Italian divisions with complete war material form the spearhead of the rebel advance in Catalonia, in Rome not only is this fact openly declared but the official 'Diplomatic Bulletin' announces that this aid will be increased as much as necessary.

The Prime Minister in Rome apparently accepted this position. The 'agreement to differ', according to the diplomatic correspondents, is that 'Britain will adhere to non-intervention while Italy adheres to intervention'. In other words, while the Republican Government is to continue to be deprived of its right to trade and purchase arms and has loyally fulfilled its undertakings by withdrawing every one of its foreign volunteers, under supervision of the League of Nations Commission, the right has been recognised of the Italian Government to pursue military intervention in defiance of its repeated pledges.

British policy has been declared again and again to be "to enable the Spanish people to settle their own affairs', yet now non-intervention has become a weapon by which Mussolini is to be allowed to impose his will on the Spanish people while Britain and France tie their hands.

Since, as seems implied by the results of the Rome visit, Mr. Chamberlain now admits that nothing further can be done to get the Italian divisions out of Spain or to prevent further Italian intervention in the degree Mussolini considers necessary, there is no possible basis in law or justice for preventing the restoration to the Republican Government of its right to purchase the means for its defence. The embargoes must be lifted and the frontiers opened by Britain and France forthwith.

(14) In 1938 Jessica Mitford continued to be involved in the campaign to raise money for the International Brigades fighting in Spain.

Although mass meetings and fund-raising parties for the Loyalist cause attracted as much support as ever, the atmosphere had changed. The victorious feeling of the early days of the war had seeped away for ever. Even the magnificent Ebro offensive of that July, into which the Loyalists threw all their resources, did not basically change the desperate situation. Franco remained in control of three-fourths of the country.

As the offensive simmered down into a series of indecisive battles it was clear that slowly, day by day, the war was being lost, and that slowly, one by one. Loyalist supporters in England were beginning to give up hope.

In the draughty meeting-halls from Bermondsey to Hampstead Heath where they gathered to raise money for Spanish relief, the mood of the huge, grave audiences seemed out of step with the ever more strained optimism of platform speakers.

At the same time, the Spanish war was driven off the front pages by events in central Europe, where lines were being drawn for the last, bitter battle for collective security against the Axis. A million Germans were massed along the Czechoslovak frontier. Newspapers quoted Goering as saying he had definite information that if the German Army marched into Czechoslovakia the British would not lift a finger.

(15) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

Baldwin's retirement in May, 1937, had accentuated the appeasement policy with the arrival of Neville Chamberlain as Premier. My own view was that the chances of avoiding war were nearly over but there was still time with a definite policy of standing up to the Fascists over Spain. I opposed non-intervention in Spain and was speaking for a minority within the Labour Party. As much as feeling that it was in the interests of peace to do so I felt that this was a question of principle. It was the elementary duty of all socialists to back up the legally elected Republican Government of Spain.

In conversations with French socialists during this period, which I sought in the hopes of developing an entente about support for the Spanish Republicans which would influence the appeasers, I was disturbed to find that the French Popular Front was afraid for its life. France was so riddled with schisms that Blum dared not officially approve intervention. The French government had to resort to the pathetic policy of supplying arms to a friendly nation secretly in case it annoyed the insurgents and their Axis allies.

(16) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (28th February, 1939)

Franco and the Socialists had their last snarl today. Attlee opened the Debate, which took the form of a Vote of Censure, and he renewed his pusillanimous attack on the Prime Minister, though in so doing he lost the respect of the House, for he said little about the subject. Then, the PM rose, and never have I so admired him, though at first, I feared he would retaliate, as he looked annoyed. Instead, with sublime restraint he coolly remarked that he would resist the temptation to castigate the Leader of the Opposition, and he then proceeded to state the Government's case for the recognition of the Spanish Nationalists as the Legitimate Government of Spain. He was devastatingly clear, and made an iron-clad case which our opponents found difficult, indeed impossible, to answer. Their only reply was rage and abuse. The hours passed and it became increasingly clear that the House was Sick Unto Death of Spain, and that it recognised the necessity, indeed the urgency of establishing friendly relations with Franco, and the sooner the better.