International Brigades

In August 1936, Harry Pollitt, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, arranged for Tom Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the CPGB during the Civil War. Wintringham, along with Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, went out to Spain with the first ambulance unit paid for by the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, a Popular Front organisation supported by the Labour Party. According to the Daily Worker, it left Victoria Station to the cheers of 3,000 supporters who had marched from Hyde Park to see them off led by the Labour mayors from East London boroughs. (1)

While in Barcelona he developed the idea of a volunteer international legion to fight on the side of the Republican Army. He commented: "I believed in the idea of an international legion. Militias can do a lot. But a larger-scale example of military knowledge and discipline, and larger-scale results, are needed too. You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in. You need things big enough to be worth putting in the newspapers." (2)

In September 1936, Tom Wintringham wrote to Harry Pollitt that he had arranged for Nat Cohen, a Jewish clothing worker from Stepney, to establish "a Tom Mann centuria which will include 10 or 12 English and can accommodate as many likely lads as you can send out... I propose to join it, provided I can still write for the Daily Worker. I believe that full political value can only be got from it (and that's a lot) if its English contingent becomes stronger. 50 is not too many." (3)

Maurice Thorez, the French Communist Party leader, also had the idea of an international force of volunteers to fight for the Republic. At a meeting of Comintern, in an impassioned speech by Georgi Dimitrov, it was suggested the Communist parties in all countries should establish volunteer battalions. Joseph Stalin agreed and the Comintern began organising the formation of International Brigades. An international recruiting centre was set up in Paris and a training base at Albacete in Spain. (4)

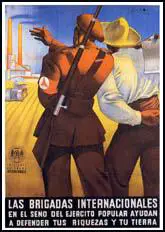

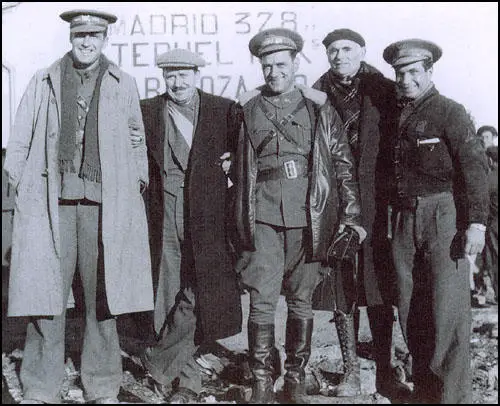

1936. Left to right: Sid Avner, Nat Cohen, Ramona, Tom Winteringham,

George Tioli, Jack Barry and David Marshall.

Joseph Stalin played an important role in the formation of the International Brigades. As Gary Kern has pointed out in A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "To start the ball rolling, he (Stalin) ordered that 500-600 foreign Communists living as refugees in the USSR, personae non grata in their own countries, be rounded up and sent to fight in Spain. This action not only rid him of a long-term irritant, but also laid the foundation for the International Brigades. The Comintern, which officially promulgated the policy of non-intervention, was enlisted to process young men in foreign countries wishing to join the Brigades. The word went out that the various Communist parties would facilitate their transport to Spain; in each CP a Comintern representative directed the program." (5)

Franklin D. Roosevelt was very sympathetic to the Republican cause. So was his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, and several members of his government, including Henry Morgenthau, secretary of the treasury, Henry A. Wallace, secretary for agriculture, Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior and Summer Welles, the assistant secretary of state. However, during the election campaign, Roosevelt made a commitment that he would not allow America to become involved in European conflicts. Cordell Hull, secretary of state, insisted that Roosevelt kept to this policy. (6)

Some people in America felt so strongly about this that they were willing to go to Spain to fight to protect democracy. As a result, the Abraham Lincoln Battalion was formed. An estimated 3,000 men fought in the battalion. Of these, over 1,000 were industrial workers (miners, steel workers, longshoremen). Another 500 were students or teachers. Around 30 per cent were Jewish and 70 per cent were between 21 and 28 years of age. The majority were members of the American Communist Party, whereas others came from the Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party. The first volunteers sailed from New York City on 25th December, 1936. (7)

Bill Bailey wrote to his mother explaining his decision to join the Abraham Lincoln Battalion: "You see Mom, there are things that one must do in this life that are a little more than just living. In Spain there are thousands of mothers like yourself who never had a fair shake in life. They got together and elected a government that really gave meaning to their life. But a bunch of bullies decided to crush this wonderful thing. That's why I went to Spain, Mom, to help these poor people win this battle, then one day it would be easier for you and the mothers of the future. Don't let anyone mislead you by telling you that all this had something to do with Communism. The Hitlers and Mussolinis of this world are killing Spanish people who don't know the difference between Communism and rheumatism. And it's not to set up some Communist government either. The only thing the Communists did here was show the people how to fight and try to win what is rightfully theirs." (8)

A large number of African-Americans joined the battalion. Canute Frankson explained his decision in a letter written to his parents: "I'm sure that by this time you are still waiting for a detailed explanation of what has this international struggle to do with my being here. Since this is a war between whites who for centuries have held us in slavery, and have heaped every kind of insult and abuse upon us, segregated and Jim-Crowed us; why I, a Negro who have fought through these years for the rights of my people, am here in Spain today? Because we are no longer an isolated minority group fighting hopelessly against an immense giant. Because, my dear, we have joined with, and become an active part of, a great progressive force, on whose shoulders rests the responsibility of saving human civilization from the planned destruction of a small group of degenerates gone mad in their lust for power. Because if we crush Fascism here we'll save our people in America, and in other parts of the world from the vicious persecution, wholesale imprisonment, and slaughter which the Jewish people suffered and are suffering under Hitler's Fascist heels." (9)

Americans were forbidden to travel to Spain to fight for the Republicans. The Manchester Guardian reported in April 1937: "Twenty-nine Americans who are alleged to have tried to cross the French frontier into Spain to enlist with the Spanish Government forces were detained last night at Muret between Toulouse and the Spanish frontier. The Americans had landed at Havre maintaining, it is stated, that they were genuine tourists. They have been brought to Toulouse for questioning." (10)

Efforts by the Roman Catholic Church in the United States to enlist support for Franco's Spain was unsuccessful. Despite the anti-clericism of the Republicans, that resulted in the killing of priests and the burning of churches during the first months of the war, a public opinion poll revealed that forty-eight per cent of Roman Catholics in the United States supported the Popular Front government. The American Committee for Spanish Nationalist Relief, sponsored by the Church, folded before it had collected 30,000 dollars - all of which had to be used for administrative expenses. Roosevelt later admitted that America's non-intervention policy "had been a grave mistake" because it "contravened old American principles and invalidated established international law." (11)

Socialists and Communists all over Europe formed International Brigades and went to Spain to protect the Popular Front government. Men who fought with the Republican Army included George Orwell, André Marty, Christopher Caudwell, Jack Jones, Len Crome, Oliver Law, Tom Winteringham, Joe Garber, Lou Kenton, Bill Alexander, David Marshall, Alfred Sherman, William Aalto, Hans Amlie, Bill Bailey, Robert Merriman, Steve Nelson, Walter Grant, Alvah Bessie, Joe Dallet, David Doran, John Gates, Harry Haywood, Oliver Law, Edwin Rolfe, Milton Wolff, Hans Beimler, Frank Ryan, Emilo Kléber, Ludwig Renn, Gustav Regler, Ralph Fox, Sam Wild and John Cornford.

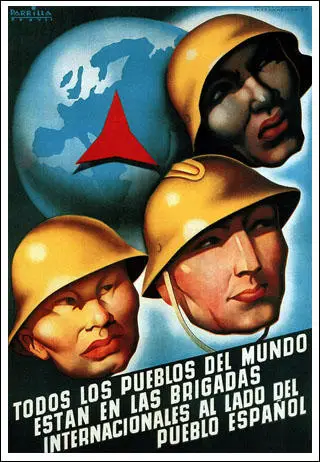

A total of 59,380 volunteers from fifty-five countries served with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. This included the following: French (10,000), German (5,000), Polish (5,000), Italian (3,350), American (2,800), British (2,000), Yugoslavian (1,500), Czech (1,500), Canadian (1,000), Hungarian (1,000) and Scandinavian (1,000). Battalions established included the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, British Battalion, Connolly Column, Dajakovich Battalion, Dimitrov Battalion, Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, George Washington Battalion, Mickiewicz Battalion and Thaelmann Battalion. (12)

Women were active supporters of the International Brigades. A large number of women volunteered to serve in Medical Units in Spain during the war. This included Annie Murray, Thora Silverthorne, Salaria Kea, Mildred Rackley, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Mary Valentine Ackland, Lillian Urmston and Penny Phelps.

After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February, 1937. General José Miaja sent the Dimitrov Battalion and the British Battalion to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. According to one source they were told by the political commissar: "We are prepared to sacrifice our lives, because this sacrifice is not only for the peace and freedom of the Spanish people, but also for the peace and freedom of the French people, the Germans, the English, the Italians, the Czechs, the Croats, and for all the peoples of the world." (13)

The following day, at what became known as Suicide Hill, the Republicans suffered heavy casualties. This included the deaths of Walter Grant, Christopher Caudwell, Clem Beckett and William Briskey. Later that day Tom Wintringham sent Jason Gurney to find out what was happening: "I had only gone about 700 yards when I came across one of the most ghastly sights I have ever seen. I found a group of wounded (British) men who had been carried to a non-existent field dressing station and then forgotten. There were about fifty stretchers, but many men had already died and most of the others would be dead by morning. They had appalling wounds, mostly from artillery. One little Jewish kid of about eighteen lay on his back with his bowels exposed from his navel to his genitals and his intestines lying in a ghastly pinkish brown heap, twitching slightly as the flies searched over them. He was perfectly conscious. Another man had nine bullet holes across his chest. I held his hand until it went limp and he was dead. I went from one to the other but was absolutely powerless. Nobody cried out or screamed except they all called for water and I had none to give. I was filled with such horror at their suffering and my inability to help them that I felt I had suffered some permanent injury to my spirit." (14)

Led by Robert Merriman, the 373 members of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion moved into the trenches on 23rd February. When the were ordered over the top they were backed by a pair of tanks from the Soviet Union. On the first day 20 men were killed and nearly 60 were wounded. Colonel Vladimir Copic, the Yugoslav commander of the Fifteenth Brigade, ordered Merriman and his men to attack the Nationalist forces at Jarama. As soon as he left the trenches Merriman was shot in the shoulder, cracking the bone in five places. Of the 263 men who went into action that day, only 150 survived. One soldier remarked afterwards: "The battalion was named after Abraham Lincoln because he, too, was assassinated." (15)

The Battle of Jarma resulted in a stalemate. The Republicans had lost land to the depth of ten miles along a front of some fifteen miles, but had retained the road to Valencia. Both sides claimed a victory but both had really suffered defeats. The International Brigades had 8,000 casualties (1,000 dead and 7,000 wounded) and the Nationalists about 6,000. The volunteers now realised that there would be no quick victory and with the rebels receiving so much help from Italy and Germany, in the long-term, they faced the possibility of defeat. (16)

Volunteers came from a variety of left-wing groups but the brigades were always led by Communists. This created problems with other Republican groups such as the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) and the Anarchists. One of the NKVD agents in Spain, Walter Krivitsky, claimed: "Stalin's intervention in Spain had one primary aim - and this was common knowledge among us who served him - namely, to include Spain in the sphere of the Kremlin's influence... The world believed that Stalin's actions were in some way connected with world revolution. But this is not true. The problem of world revolution had long before that ceased to be real to Stalin... He was also moved however, by the need of some answer to the foreign friends of the Soviet Union who would be disaffected by the great purge. His failure to defend the Spanish Republic, combined with the shock of the great purge, might have lost him their support." (17)

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of POUM, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." (18)

According to the authors of Deadly Illusions (1993) in March 1937 General Yan Berzin had sent a confidential report to War Commissar Kliment Voroshilov "reporting resentment and protests he had received about the NKVD's repressive operations from high Republican officials. It stated that the NKVD agents were compromising Soviet authority by their excessive interference and espionage in Government quarters. They were treating Spain like a colony. The ranking Red Army General concluded his report with a demand that Orlov be recalled from Spain at once." Abram Slutsky, the head of the Foreign Department of NKVD, told Krivitsky. "Berzin is absolutely right our men were behaving in Spain as if they were in a colony, treating even Spanish leaders as colonists handle natives". (19)

Krivitsky admitted: "Already in December 1936, the terror was sweeping Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia. The OGPU had its own special prisons. Its units carried out assassinations and kidnappings. It filled hidden dungeons and made flying raids. It functioned, of course, independent of the Loyalist government. The Ministry of Justice had no authority over the OGPU, which was an empire within an empire. It was a power before which even some of the highest officers in the Caballero government trembled. The Soviet Union seemed to have a grip on Loyalist Spain, as if it were already a Soviet possession." (20)

Antony Beevor, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1982), has argued: "The persistent trouble in the Brigades also stemmed from the fact that the volunteers, to whom no length of service had ever been mentioned, assumed that they were free to leave after a certain time. Their passports had been taken away on enlistment. Krivitsky claimed that these were sent to Moscow by diplomatic bag for use by NKVD agents abroad. Brigade leaders who became so alarmed by the stories of unrest filtering home imposed increasingly stringent measures of discipline. Letters were censored and anyone who criticized the competence of the Party leadership faced prison camps, or even firing squads. Leave was often cancelled, and some volunteers who, without authorization, took a few of the days owing to them, were shot for desertion when they returned to their unit. The feeling of being trapped by an organization with which they had lost sympathy made a few volunteers even cross the lines to the Nationalists. Others tried such unoriginal devices as putting a bullet through their own foot when cleaning a rifle (10 volunteers were executed for self-inflicted wounds)." (21)

Walter Krivitsky, confirmed the story about the use of passports: "Several times while I was in Moscow in the spring of 1937, I saw this mail in the offices of the Foreign Division of the OGPU. One day a batch of about a hundred passports arrived, half of them American. They belonged to dead soldiers. That was a great haul, a cause for celebration. The passports of the dead, after some weeks of inquiry into the family histories of their original owners, are easily adapted to their new bearers, the OGPU agents." (22)

As George Orwell had been fighting with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, Orwell, John McNair and Stafford Cottman were able to escape to France on 23rd June. (23)

Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. When he arrived back in England he was determined to expose the crimes of Stalin in Spain. However, his left-wing friends in the media, rejected his articles, as they argued it would split and therefore weaken the resistance to fascism in Europe. He was particularly upset by his old friend, Kingsley Martin, the editor of the country's leading socialist journal, The New Statesman, for refusing to publish details of the killing of the anarchists and socialists by the communists in Spain. Left-wing and liberal newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, as well as the right-wing Daily Mail and The Times, joined in the cover-up. (24)

Orwell did managed to persuade the New English Weekly to publish an article on the reporting of the Spanish Civil War. "I honestly doubt, in spite of all those hecatombs of nuns who have been raped and crucified before the eyes of Daily Mail reporters, whether it is the pro-Fascist newspapers that have done the most harm. It is the left-wing papers, the News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, with their far subtler methods of distortion, that have prevented the British public from grasping the real nature of the struggle." (25)

In another article in the magazine he explained how in "Spain... and to some extent in England, anyone professing revolutionary Socialism (i.e. professing the things the Communist Party professed until a few years ago) is under suspicion of being a Trotskyist in the pay of Franco or Hitler... in England, in spite of the intense interest the Spanish war has aroused, there are very few people who have heard of the enormous struggle that is going on behind the Government lines. Of course, this is no accident. There has been a quite deliberate conspiracy to prevent the Spanish situation from being understood." (26)

George Orwell wrote about his experiences of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia. The book was rejected by Victor Gollancz because of its attacks on Joseph Stalin. During this period Gollancz was accused of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). He later admitted that he had come under pressure from the CPGB not to publish certain books in the Left Book Club: "When I got letter after letter to this effect, I had to sit down and deny that I had withdrawn the book because I had been asked to do so by the CP - I had to concoct a cock and bull story... I hated and loathed doing this: I am made in such a way that this kind of falsehood destroys something inside me." (27)

The book was eventually published by Frederick Warburg, who was known to be both anti-fascist and anti-communist, which put him at loggerheads with many intellectuals of the time. The book was attacked by both the left and right-wing press. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years. As Bernard Crick has pointed out: "Its literary merits were hardly noticed... Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style." (28)

Francisco Largo Caballero came under increasing pressure from the Communist Party (PCE) to promote its members to senior posts in the government. He also refused their demands to suppress the Worker's Party (POUM). In May 1937, the Communists withdrew from the government. In an attempt to maintain a coalition government, President Manuel Azaña sacked Largo Caballero and asked Juan Negrin to form a new cabinet. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history." Negrin now began appointing members of the PCE to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. (29)

Negrin's government set out to limit the revolution and abolish the collectives. It argued that any revolution must be postponed until the war had been won. Revolution was seen as a distraction from the main business of winning the war. "It also threatened to alienate the middle class and peasants. Given the performance of the collectives, the Communists and their supporters had a number of points on their side. But the major reason why they took an anti-revolutionary line was to follow Soviet foreign policy strategy. The USSR wished to forge an alliance with Britain and France in a front against which would alarm and antagonise the western democracies and increase their hostility to the Soviet Union as well as setting them irrevocably against the Republic. The Communists therefore wanted to present the republic as a law-abiding democratic regime which deserved the approval of the western powers." (30)

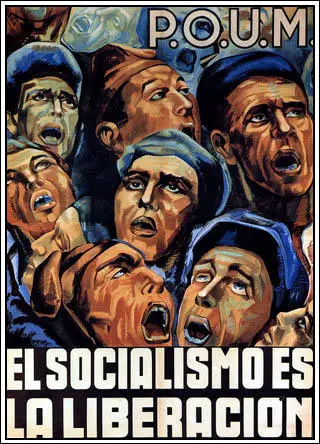

On 16th June, 1937, Negrin ruled that the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) was an illegal organisation. Established by Andres Nin and Joaquin Mauri in 1935, POUM was an revolutionary anti-Stalinist Communist party was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky. The group supported the collectivization of the means of production and agreed with Trotsky's concept of permanent revolution. POUM was very strong in Catalonia. In most areas of Spain it made little impact and in 1935 the organisation was estimated to have only around 8,000 members. (31)

After the Popular Front gained victory POUM supported the government but their radical policies such as nationalization without compensation, were not introduced. During the Spanish Civil War the Workers Party of Marxist Unification grew rapidly and by the end of 1936 it was 30,000 strong with 10,000 in its own militia. Luis Companys attempted to maintain the unity of the coalition of parties in Barcelona. POUM was disliked by the Spanish Communist Party. As Patricia Knight has pointed out: "It did not subscribe to all of Trotsky's views and its best described as a Marxist party which was critical of the Soviet system and particularly of Spain's policies. It was therefore very unpopular with the Communists." (32)

However, after the Soviet consul, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, threatened the suspension of Russian aid, Negrin agreed to sack Andres Nin as minister of justice in December 1936. Nin's followers were also removed from the government. However, as Hugh Thomas has made clear: "The POUM were not Trotskyists, Nin having broken with Trotsky on entering the Catalan government and Trotsky having spoken critically of the POUM. No, what upset the communists was the fact that the POUM were a serious group of revolutionary Spanish Marxists, well-led, and independent of Moscow." (33)

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. On 16th June, Andres Nin and the leaders of POUM were arrested. Also taken into custody were officials of those organisations considered to be under the influence of Trotsky, the National Confederation of Trabajo and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica. (34)

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." Orlov later claimed that "the decision to perform an execution abroad, a rather risky affair, was up to Stalin personally. If he ordered it, a so-called mobile brigade was dispatched to carry it out. It was too dangerous to operate through local agents who might deviate later and start to talk." (35)

Orlov ordered the arrest of Nin. George Orwell explained what happened to Nin in his book, Homage to Catalonia (1938): "On 15 June the police had suddenly arrested Andres Nin in his office, and the same evening had raided the Hotel Falcon and arrested all the people in it, mostly militiamen on leave. The place was converted immediately into a prison, and in a very little while it was filled to the brim with prisoners of all kinds. Next day the P.O.U.M. was declared an illegal organization and all its offices, book-stalls, sanatoria, Red Aid centres and so forth were seized. Meanwhile the police were arresting everyone they could lay hands on who was known to have any connection with the P.O.U.M." (36)

Nin who was tortured for several days. Jesus Hernández, a member of the Communist Party, and Minister of Education in the Popular Front government, later admitted: "Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the dry method. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin resisted the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days his face was a shapeless mass of flesh." Nin was executed on 20th June 1937. (37)

Cecil D. Eby claims that Nin was murdered by "a German hit squad from the International Brigades". The Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party of the United States, reported that "individuals and cells of the enemy had been eliminated like infestations of termites." Eby goes on to argue that the "nearly maniacal purge of putative Trotskyists in the late spring of 1937" displaced the "war against Fascism". (38)

It is believed that Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov originally intended a trial in Spain on the model of the Moscow trials, based on the confessions of people like Nin. This idea was abandoned and instead several anti-Stalinists in Spain died in mysterious circumstances. This included Robert Smillie, the English journalist who was a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Erwin Wolf, ex-secretary of Trotsky, the Austrian socialist Kurt Landau, the journalist, Marc Rhein, the son of Rafael Abramovich, a former leader of the Mensheviks, and José Robles, a Spanish academic who held independent socialist views. (39)

On 1st May, 1938, Juan Negrin proposed a thirteen-point peace plan. When this was rejected he ordered an attack across the fast-flowing River Ebro in an attempt to relieve pressure on Valencia. General Juan Modesto, a member of the Communist Party (PCE), was placed in charge of the offensive. Over 80,000 Republican troops, including the 15th International Brigade and the British Battalion, began crossing the river in boats on 25th July. (40)

Tom Murray, from Scotland, was one of the men who took part in the battle. "The crossing of the Ebro at night was a remarkable performance. The pontoons consisted of narrow buoyant sections tied together and men would sit straddled across the junctions of these sections to hold them firm, because the Ebro was a very fast-flowing river. And then others went across in boats. The mules were swum across. We went across the pontoons carrying our weapons, our machine guns. We had light machine guns as well as the heavy ones. We had five machine gun groups in our Company. No two people had to be on one section at the same time. We got across all right, lined up and marched up to the top of the hill." (41)

The men then moved forward towards Corbera and Gandesa. On 26th July the Republican Army attempted to capture Hill 481, a key position at Gandesa. Hill 481 was well protected with barbed wire, trenches and bunkers. The Republicans suffered heavy casualties and after six days was forced to retreat to Hill 666 on the Sierra Pandols. It successfully defended the hill from a Nationalist offensive on 23rd September but once again large numbers were killed, many as a result of air attacks. Bill Feeley later recalled: "I used to watch them (fascist aircraft) bomb, and you could see the bombs come out. They used to drop bombs when they were very high up. We didn't have any real anti-aircraft equipment, only machine guns mostly, because of this Non-Intervention Agreement." (42)

Over a period of 113 days, nearly 250,000 men took part in the battle at Ebro. It is estimated that a total of 13,250 soldiers were killed: Republicans (7,150) and Nationalists (6,100). About another 110,000 suffered wounds or mutilation. These were the worst casualties of the war and it finally destroyed the Republican Army as a fighting force. "Effectively, the Republic was defeated, yet it simply refused to accept the fact. Madrid and Barcelona were swelled with refugees and their populations on the verge of starvation. Negrin again began to search for a possible formula to allow a compromise peace." (43)

On 21st September 1938, Juan Negrin announced at the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. This was not a great sacrifice as there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery. (44)

The International Brigades left Barcelona on 29th October 1938. Dolores Ibárruri, made a farewell speech. "Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of state, the good of that same cause for which you offered your blood with limitless generosity, send some of you back to your countries and some to forced exile. You can go with pride. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of the solidarity and the universality of democracy. We will not forget you; and, when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic's victory, come back! Come back to us and here you will find a homeland." (45)

John Gates later wrote: "For the last time in full uniform, the International Brigades marched through the streets of Barcelona. Despite the danger of air raids, the entire city turned out. Whatever airforce belonged to the Loyalists, was used to protect Barcelona that day. Happily, the fascists did not show up. It was our day. We paraded ankle-deep in flowers. Women rushed into our lines to kiss us. Men shook our hands and embraced us. Children rode on our shoulders. The people of the city poured out their hearts. Our blood had been shed with theirs. Our dead slept with their dead. We had proved again that all men are brothers." (46)

It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. (47)

Primary Sources

(1) Jack Jones went to fight in the Spanish Civil War in 1937. He wrote about his experiences in the International Brigade in his autobiography, Union Man (1986)

The focal point for the mobilization of the International Brigades was in Paris; understandably so, because underground activities against Fascism had been concentrated there for some years. I led a group of volunteers to the headquarters there, proceeding with the greatest caution because of the laws against recruitment in foreign armies and the non-intervention policies of both Britain and France. From London onwards it was a clandestine operation until we arrived on Spanish soil.

While in Paris we were housed in workers' homes in one of the poorest quarters of the city. But it wasn't long before we were on our way, by train, to a town near the Pyrenees. From there we travelled by coach to a rambling old farmhouse in the foothills of the Pyrenees. After a rough country meal in a barn we met our guide who led us through the mountain passes into Spain.

In the light of the morning we could see Spanish territory. After five hours or so, stumbling down the mountainside (I found it almost as hard going down as climbing up), we came to an outpost and from there were taken by truck to a fortress at Figueras. This was a reception centre for the volunteers. The atmosphere of old Spain was very apparent in the ancient castle. For the first day or so we felt exhausted after the long climb. The food was pretty awful. We ate it because we were hungry but without relish.

For some the first lessons about the use of a rifle were given before we moved off to the base. I at least could dismantle and assemble a rifle bolt and knew something about firing and the care of a weapon. But my first shock came when I was told of the shortage of weapons and the fact that the rifles (let alone other weapons) were in many cases antiquated and inaccurate.

Training at the base was quick, elementary but effective. For me life was hectic, meeting good companions and experiencing a genuine international atmosphere. There were no conscripts or paid mercenaries. I got to know a German Jew who had escaped the clutches of Hitler's hordes and was then a captain in the XII Brigade. He had hopes of going on ultimately to Palestine and striving for a free state of Israel. He was not only a good soldier but a brave one too. That was also true of a smart young Mexican whom I met. He had been an officer in the Mexican Army and was a member of the National Revolutionary Party of his country.

(2) Julius Toab, a member of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, diary entry (15th January 1937)

We received a royal welcome. Men began to arrive that night. Stories of escaping from fascist Germany by swimming rivers, climbing mountains, hiking for hundreds of miles. From all parts of the world they came. Always coming. Anti-fascists. The International Brigades.

(3) Milton Wolff, interviewed by John Dolland about getting to the International Brigades training camp at Albacete (June 1942)

Most of the guys were like me, just city slickers. We were dressed in fancy shoes, in fancy clothes, and looked like anything but a mountain-climbing expedition. It was very, very grueling, going up and up, and always thinking we were reaching the top and never getting there. When we arrived, weary as we were we cheered and yelled at the top of our lungs."

(4) Claude Cockburn, The Daily Worker (21st November, 1936)

From the main streets you could already hear quite clearly the machine-gun and rifle fire at the front.

Already shells began to drop within the city itself. Already you could see that Madrid was after all going to be the first of the dozen or so big European capitals to learn that "the menace of Fascism and war" is not a phrase or a far-off threat, but a peril so near that you turn the corner of your own street and see the gaping bodies of a dozen innocent women lying among scattered milk cans and bits of Fascist bombs, turning the familiar pavement red with their gushing blood.

There were others besides the defenders of Madrid who realised that, too.

Men in Warsaw, in London, in Brussels, Belgrade, Berne, Paris, Lyons, Budapest, Bucharest, Amsterdam, Copenhagen. All over Europe men who understood that "the house next door is already on fire" were already on the way to put their experience of war, their enthusiasm and their understandings at the disposal of the Spanish people who themselves in the months and years before the Fascist attack had so often thrown all their energies into the cause of international solidarity on behalf of the oppressed and the prisoners of the Fascist dictatorships in Germany, Hungary and Yugoslavia.

It was no mere "gesture of solidarity" that these men - the future members of the International Brigade - were being called upon to carry out.

The position of the armies on the Madrid fronts was such that it was obvious that the hopes of victory must to a large extent depend first on the amount of material that could be got to the front before the German and Italian war machines smashed their way through, and secondly, on the speed with which the defending force of the People's Army could be raised to the level of a modern infantry force, capable of fighting in the modern manner.

(5) Bill Alexander, Memorials of the Spanish Civil War (1996)

Around 2,400 volunteered from the British Isles and the then British Empire. There can be no exact figure because the Conservative Government, in its support for the Nonintervention Agreement, threatened to use the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1875 which they declared made volunteering illegal. Keeping records and lists of names was dangerous and difficult. However, no-passport weekend trips to Paris provided a way round for all who left these shores en route for Spain. In France active support from French people opened the paths over the Pyrenees.

The British volunteers came from all walks of life, all parts of the British Isles and the then British Empire. The great majority were from the industrial areas, especially those of heavy industry They were accustomed to the discipline associated with working in factories and pits. They learnt from the organization, democracy and solidarity of trade unionism.

Intellectuals, academics, writers and poets were an important force in the early groups of volunteers. They had the means to get to Spain and were accustomed to travelling, whereas very few workers had left British shores. They went because of their growing alienation from a society that had failed miserably to meet the needs of so many people and because of their deep repugnance at the burning of books in Nazi Germany, the persecution of individuals, the glorification of war and the whole philosophy of fascism.

The International Brigades and the British volunteers were, numerically, only a small part of the Republican forces, but nearly all had accepted the need for organization and order in civilian life. Many already knew how to lead in the trade unions, demonstrations and people's organizations, the need to set an example and lead from the front if necessary They were united in their aims and prepared to fight for them. The International Brigades provided a shock force while the Republic trained and organized an army from an assemblage of individuals. The Spanish people knew they were not fighting alone.

(6) Annie Murray, Voices From the Spanish Civil War (1986)

I was very interested in the Spanish situation even before the Civil War, and I volunteered in 1936 through the British Medical Aid Association to go out to Spain to help the Spanish people. I went to Spain because I believed in the cause of the Spanish Republican Government. I didn't believe in Fascism and I had heard many stories of what happened to people who were under Fascist rule.

The British Medical Aid Committee was composed mostly of London doctors or British doctors, and Labour MPs, left wing MPs mostly, people like that. It had been set up specially for Spanish war aid.

I arrived at a small Spanish hospital at Huete, more or less on the Barcelona front. Huete was a little village north-east of Barcelona. From the hospital in Barcelona we used to go out in the hospital trains all round the area, behind offensives, and when there was more work to do outside of the hospital than inside. In the hospital train it was pretty gruelling, you know. On one occasion we went under a bridge to operate when bombs were falling.

Hours of duty at the hospital depended on the work, because we had many casualties at one time and not so many at other times. We just worked when we had to even if you had to get out of bed in the middle of the night, you know.

We had a lot of casualties even in the little hospital at Huete, very serious ones, terribly serious ones. Young, young men calling for their mothers. It was very sad, terrifically sad. Many of the wounds were very serious - open holes, stomachs opened up, legs off, arms off, oh, terrible, terrible. I never saw anybody shell-shocked. It was a different kind of war from the First World War. We didn't have any cases of shell-shock in the hospital. We had lots of cases of frozen feet, and that was a terrible thing because when their feet were coming round to get their blood flowing again it was a terrible painful thing. We had an awful job with that, and of course we hadn't really got the equipment to treat that sort of thing very easily. So there was a terrible lot of suffering from frozen feet. It was terribly cold in the winter, very cold up in the hills in the winter where we were, extremely cold.

Most of the casualties in our hospital of course were our own. At least eighty per cent I should think were Spaniards, the remaining were Internationals from all the countries. I met masses of Internationals. Lots of Americans, Germans, Italians, Russians and, oh, every country you could think about that sent volunteers - French, Yugoslavs. I think every country almost you could mention there were volunteers from to the anti-Fascist side.

(7) Peter Kemp, a graduate of Cambridge University, joined the Carlists during the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his experiences in his book, Mine Were of Trouble (1957)

I was ordered to report to Cancela. I found him talking with some legionaries who had brought in a deserter from the International Brigades - an Irishman from Belfast; he had given himself up to one of our patrols down by the river. Cancela wanted me to interrogate him. The man explained that he had been a seaman on a British ship trading to Valencia, where he had got very drunk one night, missed his ship and been picked up by the police. The next thing he knew, he was in Albacete, impressed into the International Brigades. He knew that if he tried to escape in Republican Spain he would certainly be retaken and shot; and so he had bided his time until he reached the front, when he had taken the first opportunity to desert. He had been wandering around for two days before he found our patrol.

I was not absolutely sure that he was telling the truth; but I knew that if I seemed to doubt his story he would be shot, and I was resolved to do everything in my power to save his life. Translating his account to Cancela, I urged that this was indeed a special case; the man was a deserter, not a prisoner, and we should be unwise as well as unjust to shoot him. Moved either by my arguments, or by consideration for my feelings. Cancela agreed to spare him, subject to de Mora's consent; I had better go and see de Mora at once while Cancela would see that the deserter had something to eat.

De Mora was sympathetic. "You seem to have a good case," he said. "Unfortunately my orders from Colonel Penaredonda are to shoot all foreigners. If you can get his consent I'll be delighted to let the man off. You'll find the Colonel over there, on the highest of those hills. Take the prisoner with you, in case there are any questions, and your two runners as escort.'

It was an exhausting walk of nearly a mile with the midday sun blazing on our backs. "Does it get any hotter in this country?" the deserter asked as we panted up the steep sides of a ravine, the sweat pouring down our faces and backs.

"You haven't seen the half of it yet. Wait another three months," I answered, wondering grimly whether I should be able to win him even another three hours of life.

I found Colonel Penaredonda sitting cross-legged with a plate of fried eggs on his knee. He greeted me amiably enough as I stepped forward and saluted; I had taken care to leave the prisoner well out of earshot. I repeated his story, adding my own plea at the end, as I had with Cancela and de Mora. "I have the fellow here, sir," I concluded, "in case you wish to ask him any questions." The Colonel did not look up from his plate: "No, Peter," he said casually, his mouth full of egg, "I don't want to ask him anything. Just take him away and shoot him.'

I was so astonished that my mouth dropped open; my heart seemed to stop beating. Penaredonda looked up, his eyes full of hatred:

"Get out!" he snarled. "You heard what I said." As I withdrew he shouted after me: "I warn you, I intend to see that this order is carried out."

Motioning the prisoner and escort to follow, I started down the hill; I would not walk with them, for I knew that he would question me and I could not bring myself to speak. I decided not to tell him until the last possible moment, so that at least he might be spared the agony of waiting. I even thought of telling him to try to make a break for it while I distracted the escorts' attention; then I remembered Penaredonda's parting words and, looking back, saw a pair of legionaries following us at a distance. I was so numb with misery and anger that I didn't notice where I was going until I found myself in front of de Mora once more. When I told him the news he bit his lip:

"Then I'm afraid there's nothing we can do," he said gently. "You had better carry out the execution yourself. Someone has got to do it, and it will be easier for him to have a fellow-countryman around. After all, he knows that you have tried to save him. Try to get it over quickly."

It was almost more than I could bear to face the prisoner, where he stood between my two runners. As I approached they dropped back a few paces, leaving us alone; they were good men and understood what I was feeling. I forced myself to look at him. I am sure he knew what I was going to say.

"I've got to shoot you." A barely audible "Oh my God!" escaped him.

Briefly I told him how I had tried to save him. I asked him if he wanted a priest, or a few minutes by himself, and if there were any messages he wanted me to deliver.

"Nothing," he whispered, "please make it quick."

"That I can promise you. Turn round and start walking straight ahead."

He held out his hand and looked me in the eyes, saying only "Thank you."

"God bless you!" I murmured.

As he turned his back and walked away I said to my two runners:

"I beg you to aim true. He must not feel anything." They nodded, and raised their rifles. I looked away. The two shots exploded simultaneously.

"On our honour, sir," the senior of the two said to me, "he could not have felt a thing."

(8) Franz Borkenau, Spanish Cockpit: An Eyewitness Account of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Spanish Civil War (1937)

It must be explained, in order to make intelligible the attitude of the communist police, that Trotskyism is an obsession with the communists in Spain. As to real Trotskyism, as embodied in one section of the POUM, it definitely does not deserve the attention it gets, being quite a minor element of Spanish political life. Were it only for the real forces of the Trotskyists, the best thing for the communists to do would certainly be not to talk about them, as nobody else would pay any attention to this small and congenitally sectarian group. But the communists have to take account not only of the Spanish situation but of what is the official view about Trotskyism in Russia. Still, this is only one of the aspects of Trotskyism in Spain which has been artificially worked up by the communists. The peculiar atmosphere which today exists about Trotskyism in Spain is created, not by the importance of the Trotskyists themselves, nor even by the reflex of Russian events upon Spain; it derives from the fact that the communists have got into the habit of denouncing as a Trotskyist everybody who disagrees with them about anything. For in communist mentality, every disagreement in political matters is a major crime, and every political criminal is a Trotskyist. A Trotskyist, in communist vocabulary, is synonymous with a man who deserves to be killed. But as usually happens in such cases, people get caught themselves by their own demagogic propaganda. The communists, in Spain at least, are getting into the habit of believing that people whom they decided to call Trotskyists, for the sake of insulting them, are Trotskyists in the sense of co-operating with the Trotskyist political party. In this respect the Spanish communists do not differ in any way from the German Nazis. The Nazis call everybody who dislikes their political regime a 'communist' and finish by actually believing that all their adversaries are communists; the same happens with the communist propaganda against the Trotskyists. It is an atmosphere of suspicion and denunciation, whose unpleasantness it is difficult to convey to those who have not lived through it. Thus, in my case, I have no doubt that all the communists who took care to make things unpleasant for me in Spain were genuinely convinced that I actually was a Trotskyist.

(9) Will Paynter, letter to Arthur Horner (26th May 1937)

To read the newspapers in England, one gets the mental picture of uniformed soldiers, the rattle of machine gun fire, the hum of aeroplanes and the crash of bombs. Such is a very incomplete picture. The real picture is seen more in the drab scenes, in the less inspiring and less terrifying aspects. To see twenty or thirty little children in a small peaceful railway station, fatherless and motherless, awaiting transportation to a centre where they can be better cared for, is to get a picture of misery. To see middle aged and old women with their worldly belongings tied within the four corners of a blanket, seeking refuge from a town or village that has been bombed, is to get a picture of the havoc and desolation. To see long queues of women and children outside the shops patiently waiting to get perhaps a half a bar of soap or a bit of butter, is to get a picture of the privation and suffering entailed.

Yet, even this is not complete, because despite this, and as a result of it, you see the quiet courage and determination of the people as a whole. It is a common sight to see the peasant farmer working in the olive grove, or the plough field within the range of rifle or machine gun fire; to see gangs of men right behind the lines who are tirelessly working to build new roads, etc.; to see men and women who remain in villages under Fascist artillery fire in order to care for the wounded. Everywhere you see a people who by courage, self sacrifice and ceaseless labour, are welded together by the common aim of maintaining their freedom and liberty from Fascist barbarism.

Havoc and ruin caused by Franco and the combined Fascist powers, but over and above it, the unconquerable loyalty and devotion of the Spanish people to the cause of democracy. This is crystallized vividly in the events in Spain today. There is a section who would promote disloyalty and disunity, but they are substantially uninfluential and futile. The vast support for the new Government is proof of this. This section will be crushed, not merely in the forma] sense by the Government, but by the invincible loyalty of the whole people.

It is when you see all this that you realise what the war is, and what it is all about. It is here that you can feel the terrible menace to France and the people of Britain if the Fascists are not crushed at this point. It is here that you really feel that the people of all countries have an obligation in rendering the maximum of assistance to the Spanish people. It is here that you really feel that the International Brigade is a necessary part of that assistance. It is here that you realise that a battle is in progress not merely to defend a people from a savage aggressor, but to destroy something that, if allowed to advance, will eventually crush the people of all democratic countries.

In other words your own senses compel you to realise that for the anti-Fascist everywhere this is a fight of self preservation. More so, it is a fight of self preservation for all those in democratic countries who would continue the small rights and liberties they are at present afforded. For those who would have the greater freedom and life under Socialism it is certainly their battleground and testing place. Because if defeat is recorded in this partial fight, then the prospects of victory for the whole is indeed pushed further into the background of abandoned hopes.

This I suppose has all been said or written before, but here it is symbolised in the most commonplace event and in the most ordinary place. It is for that reason that it becomes outstanding in one's consciousness and has to be repeated.

From it all emerges one thing at least, and that is that the International Brigade, and the British Battalion as part of it, is not some noble and gallant band of crusaders come to succour an helpless people from an injustice, it is just the logical expression of the conscious urge of democratic peoples for self preservation. No one will deny but that the Brigade has had a tremendous and inspiring effect upon the morale and fighting capacity of the Spanish people. Yet no one would claim that it was done out of pity, or as a chivalrous gesture of an advanced democratic peoples. The Brigades is the historic answer of the democratic peoples of the world to protect their democracy, and the urgency of the need for that protection would warrant an even greater response. The people who have organised and built the Brigade are those who have clearly seen the need, and who strive to direct the progress of history to the advantage of the common people.

The people of Britain should be proud of the British Battalion. It is their weapon of self preservation. Those who donate their pennies and pounds, those who give their gifts of food, those who have given their sons, brothers and husbands, to build and maintain the Battalion, are the real defenders of democracy and progress. Their sacrifice and devotion is only surpassed by that of the men who make up the Battalion and by those who have already spilled their blood.

(10) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

When we arrived in Albacete, we really got down to business. Outfitted with uniforms (French) and with rifles (Russian) still packed in cosmoline, we were assigned to units. My outfit was an experiment, an international battalion composed of four companies, an English-speaking one, a French-Belgian, a Slav and a German-Austrian. The battalion commander was Italian and the commissar French. This was an independent battalion not assigned to any of the International Brigades.

The International Brigades were five in number, each with its dominant language: French, German, Italian, Slav and English, although numerous nationalities were scattered among them. The International Brigades had their own base but for training purposes only. Actually, the brigades were part of the Spanish Re¬publican Army, subordinate to its command and discipline.

(11) Edwin Greening, letter to Dai Mark Jones about the death of his brother Tom Howell Jones (August 1938)

I regret having to write this, but Tom Howell was killed a few days ago (at 2.30 p.m., August 25 to be exact). We were together in an advanced position with the boys on some mountains called Sierra de Pandols, which overlook the town of Gandesa. I was in our company observation post, which was situated only 5 yards from where Tom was posted.

Every night Tom and I would have a little chat about home and other things, and that morning I had given him an Aberdare Leader the one in which Pen Davies' pilgrimage to the Aberdare Cemetery was reported, and he was very happy to receive it.

From early morning things had been very quiet on our sector. Then suddenly the enemy sent over some trench mortars; one of the shells made a direct hit on a machine gun post, nearly killing three men, a Spaniard and two Englishmen. I shouted to Tommy "All right there Tom?" and he shouted back, "O.K. Edwin."

Then this trench mortar landed near us. I called out again and receiving no answer, crawled to Tom's post, where I found him very badly wounded about the neck, chest and head. He was already unconscious and was passing away. I ran for the first aid man and we were there in two minutes, but Tom was, from the moment he was hit, beyond human aid and all we could do was raise him up a little and in two or three minutes, with his head resting on my knee, Tom passed away without regaining consciousness.

You can imagine how I felt because Tom and I had been very close to one another here. But I could do nothing.

That night Alun Williams of Rhondda, son of Huw Menai, and Lance Rogers of Merthyr, one of Tom's pals, carried his corpse to the little valley below, where he was to rest forever.

And there on that great mountain range, in a little grove of almond trees, we laid Tom Howell to rest. I said a few words of farewell but Tom is not alone there, all around him lie the graves of many Spanish and English boys.

Tom always made me promise to write you if anything like this happened. You will have already heard about Tom a week or two before you receive this letter.

His thoughts were to the last and always of his mother and the people at home. He lived and died a good fellow. If fifty years pass I shall not forget.

(12) André Malraux, speech in the United States (November, 1938)

The ivory tower is no place for writers who have in democracy a cause to fight for. If you live, your writing will be better for the experience gained in battle. If you die, you will make more living documents than anything you could write in ivory towers.

(13) In 1938 the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy in New York published Salaria Kea: A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain.

The hospital beds were soon filled with soldiers of every degree of injury and ailment, of almost every known race and tongue and from every corner of the earth. Czechs from Prague, and from Bohemian villages, Hungarians, French, Finns. Peoples from democratic countries who recognized Italy and Germany's invasion in Spain as a threat to the peace and security of all small countries. Germans and Italians, exiled or escaped from concentration camps and fighting for their freedom here on Spain's battle line. Ethiopians from Djibouti, seeking to recoup Ethiopia's freedom by strangling Mussolini's forces here in Spain. Cubans, Mexicans, Russians, Japanese, unsympathetic with Japan's invasion of China and the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo axis. There were poor whites and Negroes from the Southern States of the United States. These divisions of race and creed and religion and nationality lost significance when they met in Spain in a united effort to make Spain the tomb of fascism. The outcome of the struggle in Spain implies the death or the realization of the hopes of the minorities of the world.

Salaria saw that her fate, the fate of the Negro Race, was inseparably tied up with their fate; that the Negro's efforts must be allied with those of other minorities as the only insurance against an uncertain future. And in Spain she worked with freedom. Her services were recognized. For the first time she worked free of racial discrimination or limitations.

There were not too many skilled hands to make the wounded comfortable. Everybody's services were conscripted. Nurses taught carpenters to make hospital supplies - shock blocks, back rests, Balkan frames for fractured arms, Fire and fuel they needed desperately.

(14) Tom Murray, Voices From the Spanish Civil War (1986)

The International Brigade, I would say, had no tanks. We had nothing in the way of motorised equipment worth speaking about. Nearly everything was carried - boxes of ammunition and so forth were carried on our backs. For example, light machine guns had to be carried. We dismantled the heavy machine guns, and one person would carry a wheel, another would carry the carriage part of it. And up these mountains we had to climb carrying these bits and pieces and ammunition. Of course it was heavy ammunition, too, great boxes of ammunition, and so on.

(15) Eslanda Goode diary entries while in Spain visiting the International Brigades in January 1938.

Wednesday 26th January 1938: Back at Albacete in our so-called Grand Hotel. Off to Tarazona, the training camp for the International Brigade. Arrived about twelve, had a good lunch with the men.

Saw lots of Negro comrades, Andrew Mitchell of Oklahoma, Oliver Ross of Baltimore, Frank Warfield ofSt Louis. All were thrilled to see us and talked at length with Paul. All the white Americans, Canadians and English troops were also thrilled to see Paul.

A Major Johnson - a West Pointer - had charge of training. The officers arranged a meeting in the church and all the Brigade gathered there at 2:30 sharp, simply packing the church. But before they filed in, they passed in review in the square for us, saluting us with Salud! as they passed.

Major Johnson told the men that they are to go up to the front line tomorrow. The men applauded uproariously at that news.

Then Paul sang, the men shouting for the songs they wanted: 'Water Boy', 'Old Man River', 'Lonesome Road', 'Fatherland'. They stomped and applauded each song and continued to shout requests. It was altogether a huge success. Paul loved doing it. Afterwards we had twenty minutes with the men and took messages for their families.

Monday 31st January: We had a good talk over lunch and afterwards over coffee in the lounge, and then we went off to the border. Fernando, in civilian dress, accompanied us, and Lt. K., armed in full uniform, was our official escort.

As we drove along, Lt. K. got talking and told us the story of Oliver Law. It seems he was a Negro - about 33 - who was a former army man from Chicago. He had risen to be a corporal in the US Army. Quiet, dark brown, dignified, strongly built. All the men liked him. He began here as a corporal, soon rose to sergeant, lieutenant, captain and finally was commander of the Battalion - the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. K. said warmly that many officers and men here in Spain considered him the best battalion commander in Spain. The men all liked him, trusted him, respected him and served him with confidence and willingly.

Lt. K. tells of an incident when the battalion was visited by an old Colonel, Southern, of the US Army. He said to Law - 'Er, I see you are in a Captain's uniform?' Law replied with dignity, 'Yes, I am, because I am a Captain. In America, in your army, I could only rise as high as corporal, but here people feel differently about race and I can rise according to my worth, not according to my color!' Whereupon the Colonel hemmed and hawed and finally came out with: 'I'm sure your people must be proud of you, my boy.' 'Yes,' said Law. 'I'm sure they are!'

Lt. K. says that Law rose from rank to rank on sheer merit. He kept up the morale of his men. He always had a big smile when they won their objectives and an encouraging smile when they lost. He never said very much.

Law led his men in charge after charge at Brunete, and was finally wounded seriously by a sniper. Lt. K. brought him in from the field and loaded him onto a stretcher when he found how seriously wounded he was. K. and another soldier were carrying him up the hill to the first aid camp.

On the way up the hill another sniper shot Law, on the stretcher; the sniper's bullet landed in his groin and he began to lose blood rapidly. They did what they could to stop the blood, hurriedly putting down the stretcher. But in a few minutes the loss of blood was so great that Law died.

(16) After the war Ernest Hemingway wrote about the role of the International Brigades.

The dead sleep cold in Spain tonight. Snow blows through the olive groves, sifting against the tree roots. Snow drifts over the mounds with small headboards. For our dead are a part of the earth of Spain now and the earth of Spain can never die. Each winter it will seem to die and each spring it will come alive again. Our dead will live with it forever.

Over 40,000 volunteers from 52 countries flocked to Spain between 1936 and 1939 to take part in the historic struggle between democracy and fascism known as the Spanish Civil War.

Five brigades of international volunteers fought on behalf of the democratically elected Republican (or Loyalist) government. Most of the North American volunteers served in the unit known as the 15th brigade, which included the Abraham Lincoln battalion, the George Washington battalion and the (largely Canadian) Mackenzie-Papineau battalion. All told, about 2,800 Americans, 1,250 Canadians and 800 Cubans served in the International Brigades. Over 80 of the U.S. volunteers were African-American. In fact, the Lincoln Battalion was headed by Oliver Law, an African-American from Chicago, until he died in battle.

(17) Dolores Ibárruri, speech in Barcelona on 29th October 1938.

Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of state, the good of that same cause for which you offered your blood with limitless generosity, send some of you back to your countries and some to forced exile. You can go with pride. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of the solidarity and the universality of democracy. We will not forget you; and, when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic's victory, come back! Come back to us and here you will find a homeland.

(18) Per Eriksson was born in Kragenäs, Bohuslän (Swedish west coast - north of Gothenburg) 1907. He worked as a seaman when the Spanish Civil War broke out. In January 1937 he left Sweden for Spain. He joined other Scandinavians in the Thaelmann Battalion. The interview originally appeared in Swedes in the Spanish Civil War (1972)

Most of Barcelona's population were gathered around the big street Diagonal. I think there were a million people there. The city had been bombed every single hour for months. But this time the Republican airplanes were up in the air, patrolling. There was a troop-parade. There were "carabineros" in their green uniforms, Guardia Nacional and different fractions from the army, tank-troops… while the Air Force was roaring by above. Then the International troops came, straight from the front, in their shabby army-pants and shirts, not at all as well groomed as the others from the frontline. But then the crowd went wild. People were cheering and shouting. The women brought their children and handed them over to the soldiers in the International Brigade. They wanted to give them the best thing they had. It was a fantastic sight.

(19) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

It took two more months to leave Spain. Transportation had to be arranged for the long voyage back; we had to be outfitted with civilian clothes; the League of Nations had to count us; it was almost more difficult to leave Spain than it had been to get in. Meanwhile, the Spanish people wanted to give us a proper farewell. Fetes and banquets were held everywhere as people showed their gratitude to the 25,000 men from all over the world who had come to help Spain in her hour of need.

The main farewell took place in Barcelona on Oct. 29. For the last time in full uniform, the International Brigades marched through the streets of Barcelona. Despite the danger of air raids, the entire city turned out. Whatever airforce belonged to the Loyalists, was used to protect Barcelona that day. Happily, the fascists did not show up. It was our day. We paraded ankle-deep in flowers. Women rushed into our lines to kiss us. Men shook our hands and embraced us. Children rode on our shoulders. The people of the city poured out their hearts. Our blood had been shed with theirs. Our dead slept with their dead. We had proved again that all men are brothers. Matthews wrote about this final day, remarking that we did not march with much precision. "They learned to fight before they had time to learn to march."

Finally, on a day in December 1938, we boarded a train near the French frontier and left Spanish soil. The French government sealed our train and we were not permitted to get off until we reached Le Havre and the ship that was waiting to take us home. The Italian and German members of the Brigades were interned in French concentration camps; there they led a miserable existence until World War II freed them and they were able to use the experience of their Spanish days in the various Allied armies which they joined.

Three months after we crossed the Spanish border, and two years and eight months after Franco had begun his revolt, the Republic of Spain fell to the fascists. It was a bleak day for mankind.