Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway, the son of Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a doctor, was was born in Oak Park, Illinois, on 21st July, 1899. His mother, Grace Hall Hemingway, was a music teacher but had always wanted to be an opera singer. According to Carlos Baker, the author of Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story (1969), he began writing stories as a child: "Ernest loved to dramatize everything, continuing his boyhood habit of making up stories in which he was invariably the swashbuckling hero."

After being educated at the local high school, Hemingway rejected his father's idea of going to Oberlin College. Instead he accepted the offer of working for the Kansas City Star at $15 a week. He later recalled: "I covered the short-stop run which included the 15th Street police station, the Union Station, and the General Hospital. At the 15th Street station you covered crime, usually small, but you never knew when you might hit something larger. Union Station was everybody going in and out of town... some shady characters I got to know, and interviews with celebrities going through. The General Hospital was up a long hill from Union Station and there you got accidents and a double check on crimes of violence."

When the United States entered the First World War in 1917 Hemingway attempted to sign up for the army but was rejected because of a defective eye. He therefore joined the Red Cross as an ambulance driver. He later wrote: "One becomes so accustomed to all the dead being men that the sight of a dead woman is quite shocking. I first saw inversion of the usual sex of the dead after the explosion of a munition factory which had been situated in the countryside near Milan. We drove to the scene of the disaster in trucks along poplar-shaded roads. Arriving where the munition plant had been, some of us were put to patrolling about those large stocks of munitions which for some reason had not exploded, while others were put at extinguishing a fire which had gotten into the grass of an adjacent field; which task being concluded, we were ordered to search the immediate vicinity and surrounding fields for bodies. We found and carried to an improvised mortuary a good number of these and I must admit, frankly, the shock it was to find that those dead were women rather than men."

Hemingway was sent to Europe and was badly wounded on the Austro-Italian front: "There was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red. I tried to breathe but my breath would not come. The ground was torn up and in front of my head there was a splintered beam of wood. In the jolt of my head I heard somebody crying. I heard the machine guns and rifles firing across the river. I tried to move but I could not move... The Italian I had with me had bled all over my coat, and my pants looked like somebody had made currant jelly in them and then punched holes to let the pulp out... I told them in Italian that I wanted to see my legs, though I was afraid to look... So we took off my trousers and the old limbs were still there but they were a mess. They couldn't figure out how I had walked 150 yards with a load with both knees shot through and my right shoe punctured in two big places also over 200 flesh wounds."

Hemingway was hospitalized in Milan. There was talk about possible amputation but Hemingway insisted on piece-by-piece extraction of the shrapnel "no matter how long it took or how great the pain." He even pried out some of the smaller fragments as they worked their way to the surface, using the point of a penknife. One of the other patients, Henry Villard, later claimed, "we all took turns conversing with him and encouraging him to forget his wounds." He also pointed out that the nurses "liked to exhibit him to visitors as their prize specimen of a wounded hero".

In a letter to his father Hemingway wrote: "it does give you an awfully satisfactory feeling to be wounded. There are no heroes in this war... All the heroes are dead... Dying is a very simple thing. I've looked at death and really I know. If I should have died, it would have been... quite the easiest thing I ever did... And how much better to die in all the happy period of undisillusioned youth, to go out in a blaze of light, than to have your body worn out and old and illusions shattered."

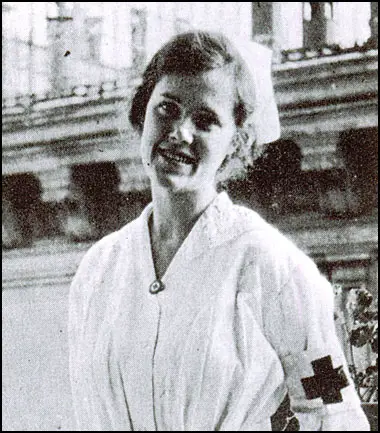

While in hospital Hemingway met and fell in love with a nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky. Hemingway described her as "a bit of heaven" who was "doubly attractive so far from home, cheerful, quick, sympathetic, with an almost mischievous sense of humour - an ideal personality for a nurse". Carlos Baker has argued: "She was beginning to reciprocate, though not to the degree that he would have liked. It was his first adult love affair - there is no trustworthy indication of any before it - and he hurled himself into it with uncommon devotion. She was the night nurse most of the time through August and early September. Although she was far too careful a nurse to neglect her other charges, her duties brought her frequently into his room, and she often returned to see him after the other boys had settled down.... Agnes refused to permit the affair to progress beyond the kissing stage. She took her duties too seriously to think of getting married and settling down, as Ernest wanted to do."

After the war Hemingway returned to the United States and worked as a journalist in Chicago. He then became a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. While in Europe he associated with a group of radical American journalists that included Max Eastman and George Seldes. Eastman, the former editor of the The Masses helped Hemingway get his work published in The Liberator and the New Masses. The American author, Gertrude Stein, who was based in Paris, also promoted Hemingway's work.

One of the world's leading journalists, Lincoln Steffens, was especially impressed with Hemingway's writing. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Among the younger men Steffens saw in Paris, Ernest Hemingway appeared to him to have the surest future, the most buoyant confidence, and the best grounds for it." Steffens told his partner, Ella Winter: "He's fascinated by cablese, sees it as a new way of writing." Winter explained: "Stef loved anything new, original, or experimental, and he especially cherished young people. He was sending Hemingway's stories to American magazines, and they were coming back, but this did not alter his opinion." Steffens told anyone who would listen: "Someone will recognize that boy's genius and then they'll all rush to publish him." Hemingway also encouraged Winter to write: "It's hell. It takes it all out of you; it nearly kills you; but you can do it."

Hemingway also came under the influence of the journalist, William Bolitho . He described him as "a strange-looking man with a white lantern-jawed face... that is supposed to haunt you if seen suddenly in a London fog". They met nearly every evening for dinner. It has been claimed that this "marked the beginning of Heminway's education in international politics." He did the same for Walter Duranty of the New York Times. Duranty later commented that Bolitho taught him "nearly all about the newspaper business that is worth knowing." He added that Bolitho "possessed to a remarkable degree... the gift of making a quick and accurate summary of facts and drawing there from the right, logical and inevitable conclusions."

Hemingway met Hadley Richardson in December, 1920. Hadley was eight years older than Hemingway and hen she expressed misgivings about their age difference, he "protested that it made no difference at all." They married on 3rd September 1921 and a child, John Hemingway, was born in October, 1923. Ella Winter later recalled: "Hadley had straight hair and small teeth, and appeared somewhat bewildered and out of things. She tried hard to be a good wife, to ski, fish, shoot, and attend prize fights with her husband, run a household on very little money, as well as care for their bouncing baby, Bumbie (John). He was large, blond, good-natured, and loved by everyone."

Hemingway's first collection of stories, In Our Time, was published in 1925. His novel, The Torrents of Spring, appeared the following year. However, it was his next book, The Sun Also Rises (1926), a novel about the aftermath of the First World War, that brought him to the attention of the literary critics. The journalist John Gunther met Hemingway in 1926 at the home of Ford Madox Ford. Gunther told his friend, Helen Hahn: "Put that name down. Ernest Hemingway. He can think straight and he can write English. Heaven knows two such joined accomplishments are rare nowadays."

Other books published during this period was a collection of short stories, Men Without Women (1927) and a A Farewell to Arms (1929), a novel based on his love affair with Agnes von Kurowsky and his experiences of working with the Red Cross. He also wrote a study of bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon (1932), a collection of short-stories, Winner Take Nothing (1933) and an account of big-game hunting, The Green Hills of Africa (1935).

Hemingway reported on the Spanish Civil War, where he advocated international support for the Popular Front Government. In February 1937 Hemingway went to Spain and reported on the war in the Madrid area. He spent most of his time with the International Brigades. Hemingway also helped the Dutch film director Joris Ivens make The Spanish Earth.

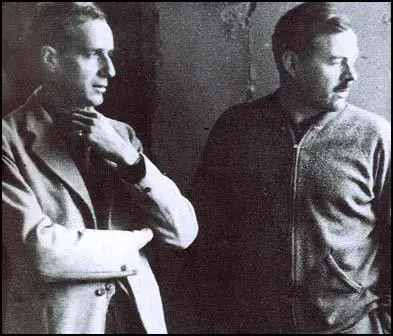

Hemingway spent a lot of time with Herbert Matthews in Spain. Alvah Bessie met them at Ebro: "One was tall, thin, dressed in brown corduroy, wearing horn-shelled glasses. He had a long, ascetic face, firm lips, a gloomy look about him. The other was taller, heavy, red-faced, one of the largest men you will ever see; he wore steel-rimmed glasses and a bushy mustache. These were Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and Ernest Hemingway, and they were just as relieved to see us as we were to see them."

Hemingway returned briefly to the United States where he met President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss the war. He also made speeches in an attempt to raise money for the Republican Army. In March 1938 Hemingway returned to Spain and toured the areas still under the control of the Popular Front Government. He also wrote the play The Fifth Column, which promoted the Republican cause.

After the war Hemingway wrote the novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). The book, which deals with the Republican partisans in the Sierra de Guadarrama, sold over 270,000 copies in its first year. A former member of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, the writer Alvah Bessie, later complained about the book: "His (Hemingway) dedication to the cause of the Spanish Republic was never questioned, even though the VALB men attacked his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, as a piece of romantic nonsense when it was not slanderous of many Spanish leaders we all revered, and scarcely representative of what the war was all about."

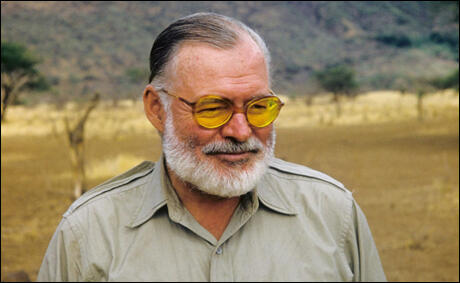

Hemingway, who married Martha Gellhorn in 1940, worked as a war correspondent during the Second World War. After the war Hemingway moved to Cuba where he wrote The Old Man and the Sea (1952), a novel that won the Pulitzer Prize. Two years later Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature.

Ernest Hemingway, depressed by failing artistic and physical powers, committed suicide on 2nd July, 1961. According to his friend, Alvah Bessie: "Ernest Hemingway committed suicide on 2 July 1961. He had apparently felt that he was through - both as a writer and a man." A Moveable Feast, a memoir of his years in Paris after the First World War, and two novels, Islands in the Stream and The Garden of Eden, were published after his death.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernest Hemingway later wrote about his experiences working with the Red Cross during the First World War.

One becomes so accustomed to all the dead being men that the sight of a dead woman is quite shocking. I first saw inversion of the usual sex of the dead after the explosion of a munition factory which had been situated in the countryside near Milan. We drove to the scene of the disaster in trucks along poplar-shaded roads. Arriving where the munition plant had been, some of us were put to patrolling about those large stocks of munitions which for some reason had not exploded, while others were put at extinguishing a fire which had gotten into the grass of an adjacent field; which task being concluded, we were ordered to search the immediate vicinity and surrounding fields for bodies. We found and carried to an improvised mortuary a good number of these and I must admit, frankly, the shock it was to find that those dead were women rather than men.

(2) Ernest Hemingway was badly wounded while on the front-line in Italy in July, 1918.

There was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red. I tried to breathe but my breath would not come. The ground was torn up and in front of my head there was a splintered beam of wood. In the jolt of my head I heard somebody crying. I heard the machine guns and rifles firing across the river. I tried to move but I could not move.

(3) Ernest Hemingway was interviewed by a representative of the Spanish Press Agency on 11th May 1937.

All civil wars are naturally long. It takes months, sometimes years, to create a war organisation of the front and the rear and to turn thousands of ardent civilians into soldiers. And this transformation can only take place by their going through the living experience of battle. If you neglect this fundamental rule you risk getting a false idea of the character of the Spanish civil war.

A great number of American newspapers, admittedly in good faith, not very long ago were giving their readers the impression that the Government was losing the war owing to its military inferiority at the outbreak of the conflict. The error of these American newspapers was to mistake the character of the civil war, and not to deduce from it the logical conclusions of the history of the American Civil War.

The Spanish military situation, following the encouraging days of March, has consistently improved. A new regular army is taking shape which is a model of discipline and courage and which is secretly developing new cadres in the military academy and schools. I sincerely believe that this new army, born of the struggle, will shortly be the admiration of all Europe, despite the fact that hardly two years ago the Spanish army was considered an agglomeration of individuals resembling actors in a comic opera.

As a war correspondent I must say that in few countries does a journalist find his task facilitated to such a degree as in Republican Spain, where a journalist can really tell the truth and where the censorship helps him in his work, rather than impeding him. While the authorities in the rebel zone do not permit journalists to enter conquered cities until days after, in Republican Spain journalists are asked to be eye-witnesses of events.

(4) Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle (1939)

At Ebro... the country was so mountainous it looked as though a few machine-guns could have held off a million men. We came back down, went up side roads, crossroads, through small towns, and on a hillside near Rasquera we found three of our men: George Watt and John Gates (then adjutant Brigade Commissar), Joe Hecht. They were lying on the ground wrapped in blankets; under the blankets they were naked. They told us they had swum the Ebro early that morning; that other men had swum and drowned; that they did not know anything of Merriman or Doran, thought they had been captured. They had been to Gandesa, had been cut off there, had fought their way out, travelled at night, been sniped at by artillery. You could see they were reluctant to talk, and so we just sat down with them. Joe looked dead.

Below us there were hundreds of men from the British, the Canadian Battalions; a food truck had come up, and they were being fed. A new Matford roadster drove around the hill and stopped near us, and two men got out we recognized. One was tall, thin, dressed in brown corduroy, wearing horn-shelled glasses. He had a long, ascetic face, firm lips, a gloomy look about him. The other was taller, heavy, red-faced, one of the largest men you will ever see; he wore steel-rimmed glasses and a bushy mustache. These were Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and Ernest Hemingway, and they were just as relieved to see us as we were to see them. We introducd ourselves and they asked questions. They had cigarettes; they gave us Lucky Strikes and Chesterfields. Matthews seemed to be bitter; permanently so.

Hemingway was eager as a child, and I smiled remembering the first time I had seen him, at a Writers' Congress in New York. He was making his maiden public speech, and when it didn't read right, he got mad at it, repeating the sentences he had fumbled, with exceptional vehemence. Now he was like a big kid, and you liked him. He asked questions like a kid: "What then? What happened then? And what did you do? And what did he say? And then what did you do?" Matthews said nothing, but he took notes on a folded sheet of paper. "What's your name?" said Hemingway; I told him. "Oh," he said, "I'm awful glad to see you; I've read your stuff." I knew he was glad to see me; it made me feel good, and I felt sorry about the times I had lambasted him in print; I hoped he had forgotten them, or never read them. "Here," he said, reaching in his pocket. "I've got more." He handed me a full pack of Lucky Strikes.

(5) Ernest Hemingway, speech at a meeting of the Writers' Congress (4th July, 1937)

A writer's problem does not change. He himself changes, but his problem remains the same. It is always how to write truly and having found what is true, to project it in such a way that it becomes part of the experience of the person who reads it. Really good writers are always rewarded under almost any existing system of government that they can tolerate. There is only one form of government that cannot produce good writers, and that system is fascism. For fascism is a lie told by bullies. A writer who will not lie cannot live and work under fascism.

(6) Mary Rolfe was in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She wrote a letter to Leo Hurwitz about her experiences on 25th November, 1938.

Hemingway was here for a few days - but once you meet him you're not likely to forget him. The day he came I had been slightly sickish, but Ed came up and got me up out of bed to meet him. When I came into the room where he was he was seated at a table and I wasn't prepared for the towering giant he is. I almost got on my toes to reach his outstretched hand - I didn't need to, but that was my first reaction. He's terrific - not only tall but big - in head, body, hands. "Hello", he said - looked at me and then at Ed and said "You're sure you two aren't brother and sister?" which meant - "what a pair of light-haired, pale, skinny kids!" He told us another time when we were driving back to the hotel from somewhere of his correspondence with Freddy Keller - how he told Freddy he's got good stuff, but he must study - must educate himself and above all study Marx. That was what he had done all winter in Key West, he told us - otherwise, he said, you're a sucker - you don't know a thing until you study Marx. All of this said in short jerky sentences - with no attempt at punctuation. Before he left he gave us the remainder of his provisions - not in a gesture, just gave them to us because he knew we needed them and because he wanted to give them to us. I'm still a little awed by the size of him - he's really an awfully big guy!

(7) After the Spanish Civil War Ernest Hemingway wrote about the role of the International Brigades.

The dead sleep cold in Spain tonight. Snow blows through the olive groves, sifting against the tree roots. Snow drifts over the mounds with small headboards. For our dead are a part of the earth of Spain now and the earth of Spain can never die. Each winter it will seem to die and each spring it will come alive again. Our dead will live with it forever.

Over 40,000 volunteers from 52 countries flocked to Spain between 1936 and 1939 to take part in the historic struggle between democracy and fascism known as the Spanish Civil War.

Five brigades of international volunteers fought on behalf of the democratically elected Republican (or Loyalist) government. Most of the North American volunteers served in the unit known as the 15th brigade, which included the Abraham Lincoln battalion, the George Washington battalion and the (largely Canadian) Mackenzie-Papineau battalion. All told, about 2,800 Americans, 1,250 Canadians and 800 Cubans served in the International Brigades. Over 80 of the U.S. volunteers were African-American. In fact, the Lincoln Battalion was headed by Oliver Law, an African-American from Chicago, until he died in battle.

(8) Ernest Hemingway, Under the Ridge (1938)

It was a bright April day and the wind was blowing wildly so that each mule that came up the gap raised a cloud of dust, and the two men at the ends of a stretcher each raised a cloud of dust that blew together and made one, and below, across the flat, long streams of dust moved out from the ambulances and blew away in the wind.

I felt quite sure I was not going to be killed on that day now, since we had done our work well in the morning, and twice during the early part of the attack we should have been killed and were not; and this had given me confidence. The first time had been when we had gone up with the tanks and picked a place from which to film the attack. Later I had a sudden distrust for the place and we had moved the cameras about two hundred yards to the left. Just before leaving, I had marked the place in quite the oldest way there is of marking a place, and within ten minutes a six-inch shell had lit on the exact place where I had been and there was no trace of any human being ever having been there. Instead, there was a large and clearly blasted hole in the earth.

Then, two hours later, a Polish officer, recently detached from the battalion and attached to the staff, had offered to show us the positions the Poles had just captured and, coming from under the lee of a fold of hill, we had walked into machine-gun fire that we had to crawl out from under with our chins tight to the ground and dust in our noses, and at the same time made the sad discovery that the Poles had captured no positions at all that day but were a little further back than the place they had started from. And now, lying in the shelter of the trench, I was wet with sweat, hungry and thirsty and hollow inside from the now-finished danger of the attack.

(9) Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle (1939)

Ernest Hemingway committed suicide on 2 July 1961. He had apparently felt that he was through - both as a writer and a man. His dedication to the cause of the Spanish Republic was never questioned, even though the VALB men attacked his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, as a piece of romantic nonsense when it was not slanderous of many Spanish leaders we all revered, and scarcely representative of what the war was all about.

© John Simkin, April 2013