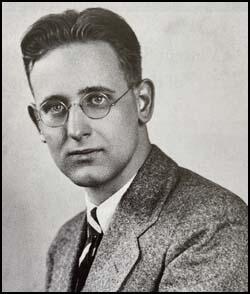

John Gunther

John Gunther, the son of Eugene and Lizette Gunther, was born in Chicago on 30th August, 1901. Both his parents were children of German immigrants. His mother, who came from an academic family was a schoolteacher. His father was an unsuccessful salesman: "Eugene had one disreputable job after another: peddling cigars and fake liquor; fishy dealings in real estate; and, worst of all, managing a garage, home every night with grease-stained trousers." (1)

John and his sister, Jean, both suffered from ill-health as children. John later recalled: "We were lonely children. We both disliked games." John hated sport and spent most of his spare-time reading books. He later recalled: "Always I had dreams of Europe. These must have started (my mother's influence) when I was a child." (2)

While at High School he began reading the poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay and the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens and George Eliot. He also became interested in the work of journalists and critics such as H. L. Mencken, George Seldes, George J. Nathan and Burton Rascoe. (3)

Gunther enrolled at the University of Chicago. At first he studied Chemistry but later changed to History and English. Gunther's student friend, Vincent Sheean, later recalled: "The University of Chicago, one of the largest and richest institutions of learning in the world, was partly inhabited by a couple of thousand young nincompoops whose ambition in life was to get into the right fraternity or club, go to the right parties, and get elected to something or other." (4)

Unlike most of his fellow students, Gunther took his studies seriously. He was especially interested in modern literature and was very impressed with Sinclair Lewis, the author of the highly successful Main Street, which questioned the morality of small town, middle-America. Gunther also liked the work of James Branch Cabell, whose novel, Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice, was suppressed for several years after its publication on grounds of obscenity. (5)

Gunther became a member of staff of The Chicago Maroon, the university newspaper. He specialized in book reviews and in 1921 his work was published by various newspapers. The following year, H. L. Mencken commissioned an article on Higher Learning in America: The University of Chicago, for his magazine, The Smart Set. (6)

Chicago Daily News

Soon afterwards Gunther provided a regular column for the Chicago Daily News, that had a circulation of 375,000. In July 1923 Gunther met Helen Hahn, an older sister of Emily Hahn. Gunther fell for her the moment they met. Ken Cuthbertson, argued in Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992): "When Helen was working or otherwise engaged, John dated her two older sisters, Rose and Dauphine, and occasionally the younger Emily... John was deeply and hopelessly in love with Helen. He was also jealous of her many other suitors. John was determined to marry Helen, and during a year of dogged pursuit he became a familiar figure around the Hahn's North Side home... Helen eventually made it clear to John that she regarded their relationship as mostly platonic. He was insistent that it be something more... She enjoyed his company and spent much time with him, but she did not find him physically attractive; the chemistry just was not there." (7)

He also provided freelance articles for magazines such as American Mercury. However, in April 1926, decided to resign from his $55-per-week job with the Chicago Daily News to seek work in England. His mother wrote to him pointing out: "All the things I have longed to do, you are doing. You are the dearest thing in the world to me... By the way, I wish you'd notice the spelling of receive and leisure!" (8)

On 22nd October, 1924, he left the United States on the RMS Olympic . On his arrival he visited the Chicago Daily News office on Trafalgar Square to meet bureau chief Hal O'Flaherty. After a brief discussion, O'Flaherty offered him a job as his assistant. This involved writing several articles about leading writers such as Hugh Walpole, G. K. Chesterton and Frank Swinnerton. (9)

In February 1925, O'Flaherty was replaced by Paul Scott Mower, who played an important role in the development of his career. "Paul Scott Mower, a keenly sensitive and percipient man, saw presently that I was not much good at spot news. Indeed, I have scarcely ever had a scoop in my life, and it seemed to me abysmally silly, then as now, to break a neck trying to beat the opposition by a few seconds on a story, although I knew why it was necessary. Paul realized that my talents, if any, lay elsewhere. It seems that I had a knack for being readable about situations and people, and I was nimble with feature stories." (10)

During this period Gunther met Raymond Gram Swing, who was working at the London bureau of the Philadelphia Daily Ledger and the New York Post. Despite a fourteen-year-age difference, the two men became close friends. Swing also introduced Gunther to another journalist, Dorothy Thompson, who was soon to be appointed as the Berlin bureau chief. Ken Cuthbertson has pointed out: "Thompson, who was taken with John Gunther, befriended him both as a young man and a pupil. Theirs was an intimate, albeit platonic (as far as is known), relationship which endured through good times and bad." (11)

At a meeting addressed by Emma Goldman, Gunther met Rebecca West. The two soon became lovers. West described Gunther as my "young and massive Adonis with curly blond hair." Gunther, who was nine years younger than West wrote to Helen Hahn saying that he was "a little afraid of her". According to Victoria Glendinning, the author of Rebecca West: A Life (1987): "Rebecca entertained John Gunther, smothered him in maternal affection, and introduced him to writers and loved him dearly in a carefree way." (12)

Gunther also met the young English critic-novelist, J. B. Priestley, who had just published English Comic Characters (1925). Gunther was very impressed and wrote to Helen Hahn: "Please put him (Priestley) down in some book and underline him with red ink. Then, 20 years from now, thank me for first discovering a great critic. I mean this very seriously - Priestley is a comer." Gunther was correct in his assessment and three years later he published the best-selling novel, The Good Companions. (13)

Rebecca West introduced Gunther to Eric Maschwitz, who worked for a publisher but really wanted to write novels. Gunther described Maschwitz as "Tall, 25, black hair falling down over his forehead, tortoise shell glasses." The two men soon became close friends and decided to go on holiday together in France. Eric's wife, the actress, Hermione Gingold, also joined them on their visit. However, after a week Maschwitz ran out of money and was forced to return to London. (14)

Francis Fineman

While in Paris Gunther met Frances Fineman, a pretty, blonde-haired expatriate journalist from New York City. The two soon became lovers. Francis also introduced Gunther to Ford Madox Ford and Ernest Hemingway. Gunther described Ford as "England's most promising young man for about 40 years." He was more impressed with Hemingway and told Helen Hahn: "Put that name down. Ernest Hemingway. He can think straight and he can write English. Heaven knows two such joined accomplishments are rare nowadays." (15)

Gunther was entranced by Frances who he described as "a small corn-colored haired creature". He admitted that "she tantalized him, excited him more than he'd been excited before". His friends started to call her the "fatal Frances" (16) Gunther told Helen Hahn: "This Francis girl is fun. She is small and blond and has just returned from six months alone in Moscow whither she went looking for adventure." (17)

Despite their contrasting personalities, Francis Fineman was attracted towards Gunther: "He was bright, warm, generous, amicable, and seemed bound for a successful career in journalism. What's more, his commanding physical presence promised a physical security she craved. She was irresistibly drawn to him. The irony was that his mannerisms and fair hair reminded her of her hatred stepfather. (18)

In 1926 Martin Secker agreed to publish Gunther's first novel, The Red Pavilion in London and Cass Canfield at Harper & Brothers in New York City. The novel was based on Gunther's relationship with Helen Hahn. The Spectator praised the novel as "one of the best, most cultivated and human of recent American books". The New York Times also liked the novel and commented on Gunther's mastery of the "technique of this genuinely sophisticated novel." However, The Saturday Review dismissed the book as "exceedingly pretentious and at times irritating". The sales of the book improved when it was banned in Boston because it was claimed that the novel was "morally objectionable". (19)

Gunther continued to work for Chicago Daily News and became close friends with other American foreign correspondents including Dorothy Thompson, Hubert Knickerbocker, Vincent Sheean, George Seldes, Raymond Gram Swing, Walter Duranty and William L. Shirer. He was especially close to Shirer and Sheean. Shirer recalled: "We were, the three of us, Chicago kids, and we all had a lot of luck. Jimmy was the best writer of the three of us and a deeper thinker than John or me, I think." (20)

Gunther married Frances Fineman in Rome on 16th March, 1927. According to Ken Cuthbertson Frances had come from a troubled background: "In 1911 her mother ran off with a well-to-do Texan named Morris Brown, whom she eventually married. She then took her daughter with her when she went to live at her new husband's home in Galveston... Frances had been deeply attached to her natural father. Her feelings of betrayal at the breakup of her parents' marriage turned to hatred for a stepfather who sexually abused her. The depth of Frances' emotional trauma manifested itself in later life in the form of a self-destructive ambivalence towards men. She was filled with a seething mistrust and resentment of males, yet she craved the paternal affection that had been denied her." (21)

Although he was officially a journalist Gunther wanted to become a successful novelist. However, according to Deborah Cohen "his characters were stilted, his dialogue contrived and not enough happened in his plots. (22) Gunther spent his spare time writing his second novel, Eden for One: An Amusement. "The story is about Peter Lancelot, a small boy with a penchant for dreaming. When a magician named Mr. Dominy causes Peter's every desire to come true, the boy promptly wishes himself into an idyllic new world for which, Mr. Dominy conjures up an island, a garden, a castle, a friend, and a lover. But in a moralistic twist, life in this paradise inevitably goes sour." When it was published by Harper & Brothers in New York City in the autumn of 1927 it received poor reviews. (23)

John Gunther's friend, Louis Fischer, pointed out: "Big and made bigger by baggy suits, jovial, friendly, he was good company. He was writing a novel in those days, and he did not yet realize the public would prefer books psychoanalyzing continents to novels psychoanalyzing individuals in love." (24)

Walter Duranty and Moscow

In August 1928 Gunther travelled to the Soviet Union and spent time with Walter Duranty who had been the New York Times correspondent in the Soviet Union since the Russian Revolution. Gunther was dazzled by the architecture he saw there, particularly the towering St Basil's a beautiful sixteenth century church on Red Square. He described it as "surely the most fantastic church in the world; Ivan the Terrible blinded the architect so that another church never could be made like it. It had eleven spires and domes in green, red, yellow and gold, scaled pineapple, obliquely burred, convoluted, transversely stripped. To the right, the red wall of the Kremlin stretches between lofty towers." (25)

Gunther was fascinated by the Moscow's street life. "He described in vivid detail the colourful scenes at the small, free-enterprise markets and on the street corners, where buskers, hawkers, and a myriad of itinerant sidewalk tradesmen gathered nightly to sell their wares". (26) As he wrote in the Chicago Daily News: "Perhaps the first impression is the almost total absence of automobiles. The few that we do see are relics of an almost neolithic past, strange monsters with distorted body lines, paintless fenders, grotesquely fanciful hoods." (27)

Gunther later admitted that in his articles he had relied too heavily on information provided by Walter Duranty. It has been argued by James William Crowl, the author of Angels in Stalin's Paradise (1982) that Duranty had been corrupted by the Soviet government. He had been given a rent free building in central Moscow. In his new home he entered visitors like Gunther, Sinclair Lewis and George Bernard Shaw. (28) One foreign visitor later recalled Duranty was a brilliant and captivating raconteur and "had a kind of magic... an evening with him was like an evening with no one else." (29)

Harrison Salisbury has argued that during the years Duranty reported from Moscow, he was one of the highest-paid correspondents in the world. It is believed that he was paid $10,000 a year, plus expenses. Duranty admitted in his autobiography, I Write As I Please (1935) admitted that he was a regular at the Savoy's poker games, a bridge partner for the Greek ambassador, and a sought-after guest at many embassy parties and was often in the city's finest night-spot, the Grand Hotel. Here in a brilliantly chandeliered room complete with musicians, Duranty enjoyed caviar, Caucasian wines and Armenian brandy. (30)

Other journalists, such as William Henry Chamberlin, believe he was in the pay of the Soviet government. Eugene Lyons, who by this time held extreme right-wing views argued that Duranty was under the control of the KGB while living in Moscow. Lyons was told by the wife of Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet Foreign Commissar, "that she walked in on a scene at the Paris Embassy when Duranty was receiving some cash." (31) Malcom Muggeridge claimed that one of his contacts "believed that he had somehow got himself into some kind of financial scandal which put him at the mercy of the authorities." (32)

Frances Fineman believed that John Gunther was easily fooled because of his inability to analyse. Her criticisms began with her husband's lack of interest in politics. "What about those interviews of yours? You ask a man what he ate for breakfast and you write about the contours of his waxed moustache, but why? Does any of it matter? If you're going to understand anything, she insisted, you can't glide along the surface." (33)

Chicago

John and Frances returned to live in Chicago. Judith Gunther was born on 25th September, 1928. Unfortunately she died four months later. An autopsy revealed that she was a victim of an undiagnosed thymus ailment known as status thymicolymphaticus. Ken Cuthbertson has pointed out: "Tortured by feelings of guilt at having aborted several unwanted pregnancies, she now became obsessed with the notion that Judy's death was a cruel form of divine retribution for her past indiscretions." (34)

"It's Judy's day," Frances would write on the baby's birthday in the years that followed. "Whenever you do anything grand, I always want to tell her," she told John. "I'd have been so much happier if my sweet little daughter hadn't died, she said of herself later. They buried Judy in Chicago. Then they went to Carmel for a holiday. It was there, in a cottage by the sea, that their second child, Johnny, was conceived. (35)

Gunther made his radio broadcasting debut on Chicago station WMAQ. The Chicago Daily News reported: "The first few words were fuzzy, while engineers had fumbled with equipment, but then Gunther's voice was heard with remarkable clarity." One critic claimed that Gunther had a clear radio voice that reminded him of movie actor James Stewart. Gunther considered radio easy work and easy money but dismissed broadcasting as not being "serious journalism". The American public felt otherwise and from the beginning, overseas radio news reports were a novelty, and were among the most widely listened to programs. (36)

Gunther also wrote freelance articles and in October, 1929, Harper's Magazine published a much acclaimed article on Al Capone and other gangsters in Chicago. Entitled, "The High Cost of Hoodlums", Gunther argued that 600 hoodlums had succeeded in terrorizing Chicago's three million citizens. He pointed out that gangsters could have an enemy "bumped off" for as little as $50. However, the going-rate for a newspaper man, like himself, was $1,000. (37)

In June 1930, Gunther became the Chicago Daily News journalist based in Vienna. He soon became close friends with Marcel Fodor, who worked for the Manchester Guardian. Another friend working in the city was William L. Shirer. The two men played tennis together. They also explored the city together and Gunther later recalled that it was "the friendliest city in Europe". Shirer argued that Gunther was an excellent journalist: "John Gunther would go to a country and he'd immediately want to know who had the power, who made the decisions, who had the money, those sorts of things. Wherever he went, he'd always want to interview the king, or the president, or the prime minister." (38)

John Gunther "The later recalled: "1930's were the bubbling, blazing days of American foreign correspondents in Europe... This was before journalism became institutionalized. We correspondents were strictly on our own. We avoided official handouts. We were scavengers, buzzards, out to get the news, no matter whose wings got clipped... I was ravenously interested in human beings. I never really got a big scoop in my life, and the little ones got were just plain accidents. I wasn't one of those reporters who managed to be on the scene when things happened. I was generally somewhere else. Matter of fact, I never really gave a damn about spot news. The idea of beating The Associated Press by six minutes bored me silly." (39)

Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis in Vienna in 1930.

Dorothy Thompson, Hubert Knickerbocker, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Marcel Fodor and George Seldes were other newspaper friends who also spent a lot of time in the city during this period. They used to meet at the Café Louvre. A student, J. William Fulbright, on a visit to the city, later recalled: "You could find a group of journalists there most evenings. I remember hearing Fodor hold forth, and he and I became friends. Fodor was a short, stocky man with a mustache, and it was obvious that he was very intelligent; he spoke with great authority on an astounding range of subjects... He had an insatiable curiosity about everything and was a natural teacher." (40)

Richard Rovere described Gunther in the 1930s as being "tall and blond, with a bulldozer frame, blue eyes, a ruddy complexion, and incongruously delicate features." When he met the film actress, Tallulah Bankhead for the first time, she said: "I'm in a helluva fix, because I think you're a writer, yet you look like a football player." Gunther asked why this mattered and she replied: "Because I don't know whether to be witty or sexy". (41)

Gunther's biographer, Ken Cuthbertson, pointed out in Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) that: "John Gunther was a larger-than-life figure who embraced life with passion... Gunther was an amiable, fair-haired bear of a man. His abiding passions in life were not political, but rather good company, gourmet food and drink, fine clothing, and beautiful women. As someone once noted, he had no friends, only best friends. John Gunther was a larger-than-life figure who embraced life with passion." (42)

Gunther became infatuated with the young actress, Luise Rainer. Although she was only twenty years old she had already appeared in a couple of German-language films and was clearly a future big star. Gunther's friend, William L. Shirer, pointed out that this caused problems for his relationship with his wife, Frances Fineman Gunther: "He fell for her to an extent that I don't think Frances was pleased. John had a roving eye and liked to flirt." (43) Rainer later recalled: "He was tall, husky, and blond. He was, of course, very bright and had a great sense of humor. I thought he was a terribly nice fellow... However, I must say something simply and brusquely: I was never in love with him, or anything of that kind." (44)

In 1932 John Gunther was elected president of the correspondents' association in Vienna. One of his duties was to arrange informal weekly luncheons for local and visiting celebrities and dignitaries. People that Gunther invited to these luncheons included Oswald Garrison Villard, Margot Asquith, H. G. Wells, Rebecca West and Engelbert Dollfuss. (45)

In the summer of 1934 Gunther and Marcel Fodor visited the birthplace of Adolf Hitler. In the Austrian town of Braunau, they sought out and interviewed Hitler's surviving relatives, including a disabled first cousin, an aged and poverty-stricken aunt, and his godfather. This was the first time foreign journalists had delved into Hitler's background. Gunther wrote in the Chicago Daily News: "There are many extraordinary things about Adolf Hitler, but surely the most amazing is that his mother was a servant girl in the household of his father's preceding wife." (46)

The Gunther-Fodor expose appeared in several European newspapers and magazines. Hitler was furious and instructed the Gestapo that the two men were to be hanged if they were caught. On 25th July, 1934, a group of 144 well-armed Austrian Nazis mounted a putsch aimed at toppling the government of Engelbert Dollfuss by storming the chancellery. Gunther was one of the first journalists on the scene: "The tawny oak doors were shut and a few policemen were outside, but otherwise nothing seemed wrong." However, the right-wing fanatics were inside the building. Faced with the prospect of surrendering or fighting to the death, the rebels laid down their arms in return for a promise of safe passage out of the building. Gunther raced upstairs to find that Dollfuss had been shot in the throat at point blank range and had bled to death. Gunther wrote: "His murder marked the entrance of gangsterism into European politics on an international basis... Dollfus died to keep anarchy out of Central Europe; and this is his best memorial." (47)

Inside Europe

In 1934 Cass Canfield of Harper & Brothers approached Hubert Knickerbocker, who had recently won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting, and suggested that he wrote a serious and comprehensive book about Europe. Knickerbocker was in the middle of another project and replied: "Try John Gunther. He's the only one with the brains, the brass, and the gusto to write the book you want." (48)

Gunther also said he was too busy. In his book, A Fragment of Autobiography (1962) Gunther wrote: "I continued to say no. In those days I was more interested in fiction than in journalism and my dreams were tied up in a long novel about Vienna that I hoped to write... I persisted in saying no to the project, and finally Miss Baumgarten asked me what, if any, financial advance would induce me to change my mind. To cut the whole matter off, I named the largest sum I had ever heard of - $5,000." (49)

Canfield said yes and in his autobiography, Up, Down and Around (1972) argued: "I had the strong feeling that the book would not only sell but blaze a new trail." (50) Gunther later recalled how he did his research for the book in the Atlantic Magazine: "I should equip myself to be able to give information, since it's always easier to ask for something if you offer something in exchange. Journalism is really a process of barter between two people who each know something and find it to their advantage to exchange or pool their knowledge." (51)

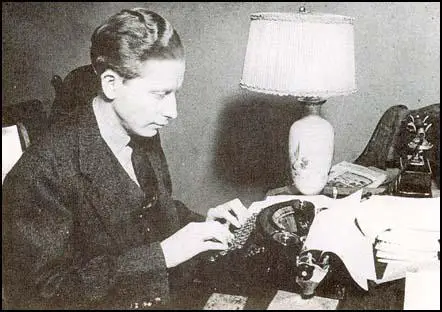

Gunther's wife, Frances Fineman Gunther, helped him with the research and in 1935 he visited London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, Warsaw and Moscow. Gunther also met Hubert Knickerbocker who was based in Nazi Germany at the time. Knickerbocker shared his vast store of firsthand inside information on Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini. (52)

Gunther finished his 190,000-word manuscript in just seven months. He typed the last words in the early hours on 2nd December, 1935. He celebrated by drinking "about a dozen beers" and dancing in the streets. It was typeset but Gunther continued to send updates until just before it was printed. This included the news that Anthony Eden had replaced Samuel Hoare in the British government. (53)

Cass Canfield published the book in its entirety in the United States but decided to hire three British lawyers to look at the manuscript before it was published in London. Several passages were removed including a reference to Joseph Goebbels "Goebbels never kicks a man until he's down". Another passage that was not published in Britain was the comment that Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, was the "head of a dwindling movement". The British government made it clear that they wanted nothing published if it damaged Anglo-German relations. It was the same concern that kept Winston Churchill from being allowed to appear on British Broadcasting Corporation radio programs. (54)

The 510-page Inside Europe was published in January 1936. Harold Nicholson, reviewed the book for The Daily Telegraph and argued: "I regard this book as a serious contribution to contemporary knowledge... Fair, intelligent, balanced and well-informed... It will provide the intelligent reader with exactly that sort of information on current affairs which he desires to possess and which he can acquire from no other equally readable source... This is one of the most educative as well as one of the most exciting books which I have read for years." (55)

A fellow journalist, Martha Gellhorn was also very impressed with the book. In a private letter she told him that she had read and reread the book and could not work out how he had done it. "How did you uncover all that dirt?" It's as if "you had at least slept with all the crowned heads of Europe". Gellhorn added that he had managed to make the dictators familiar - "to transform them from the remote, mythical personages of the newsreels to individuals as peculiar and vivid as one's own relations." (56)

Others were less complimentary. John Chamberlain said in The New York Times stated that Inside Europe was "amusing" but hardly authoritative, of literary not "scientific" value. Surely Hitler's rise wasn't an "accident of personality" but a reflection of Germany's postwar ills. Leaders, after all, required followers. (57) Clifton Fadiman, in the The New Yorker suggested if you want your history with a "chocolate coating of personalities, you can't do better than read Mr. Gunther." (58)

In an interview Gunther said: "I suppose that I write, basically, for myself, to satisfy my own sometimes peculiar curiosities. In a way, my work has been an exercise in self-education at the expense of the public. But I think I'm a pretty average person, and I have worked from the assumption that if something interests me it will probably interest the casual reader too. I have tried not to underestimate the reader's intelligence nor, at the same time, overestimate what he knows." (59)

In the opening paragraph in the book John Gunther points out: "This book is written from a definite point of view. It is that the accidents of personality play a great role in history. As Bertrand Russell says, the Russian revolution might not have occurred without Lenin, and modern European development would have been very difficult if Bismarck had died as a child. The personality of Karl Marx himself has powerfully influenced the economic interpretation of history. Important political, religious, demographic, nationalist, as well as economic factors are not, I believe, neglected in this book. But its main trend is personal." (60)

It included a 4,000-word profile of Adolf Hitler. Gunter starts his analysis with the following passage: "Adolf Hitler, irrational, contradictory, complex, is an unpredictable character; therein lies his power and his menace. To millions of honest Germans he is sublime, a figure of adoration; he fills them with love, fear, and nationalist ecstasy. To many other Germans he is meager and ridiculous - a charlatan, a lucky hysteric, and a lying demagogue. What are the reasons for this paradox? What are the sources of his extraordinary power?" (61)

As the author of Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) has pointed out: "The profile revealed in a matter-of-fact way the bizarre character of a man who eschewed friends, money, sex, religion, and physical activity in his Machiavellian quest for unbridled power; Hitler emerged as a dangerous, unpredictable ascetic, a peasant with insatiable drives and an oedipus complex as big as a house." Hitler was outraged and banned Inside Europe in Nazi Germany. (62)

The publisher, Cass Canfield, later admitted: "We figured that Inside Europe ought to sell just about 5,000 copies. That way, we'd have paid off our part of the advance and made a fairly decent profit." The first print run of 5,000 was sold out within days. (63) The main reason for this was that the book received very good reviews. Lewis Gannett of the New York Herald Tribune argued that Inside Europe was the "liveliest, best-informed picture of Europe's chaotic politics that has come my way in years." Raymond Gram Swing, writing in The Nation, pointed out that Inside Europe filled a real need at a time when America was reawakening from its self-imposed isolationism. "The vigor and almost impudent candor of this book mark it as distinctly American. I cannot imagine a man of any other nationality writing it." (64)

Eventually total sales reached 500,000 in the United States and Britain. Foreign sales amounted to at least 100,000. George Seldes later pointed out: "Everybody was envious of Gunther's success. We all asked ourselves why we hadn't thought of writing the same kind of book. I guess maybe many of us had, and that's why some people felt they could have done a better job than Gunther did. But the fact was that you really had to hand it to him - he did an excellent job." (65)

The publication of Inside Europe turned John Gunther into a well-known figure. The journalist, Richard Rovere, claimed in The New Yorker that in the late 1930s Gunther occupied an exalted position alongside Franklin D. Roosevelt and Charles Lindbergh as "one of a half-dozen or so authentic international celebrities" of the era. It is estimated that his syndicated reports, which were carried by more than 100 newspapers across North America and had a major influence on public opinion. (66)

Spanish Civil War

On 15th January 1936, by Manuel Azaña that helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left to fight the national elections due to take place the following month. This included the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party ( PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. Popular Front parties won 47.3% (285 seats) and the National Front 46.4% (131 seats) with the centre parties winning 57 seats. Socialists (99 seats), Republican Left (87 seats), Republican Unionists (37 seats), Republican Left Catalonia (21 seats) and Communist (17 seats). Paul Preston has claimed: "The left had won despite the expenditure of vast sums of money - in terms of the amounts spent on propaganda, a vote for the right cost more than five times one for the left." (67)

The government transferred right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy. In February 1936 Franco joined other Spanish Army officers, such as Emilio Mola, Juan Yague, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano and José Sanjurjo, in talking about what they should do about the Popular Front government. (68)

On 28th February 1936, magazine publisher, Margaret Haig Thomas, invited John Gunther and Aldous Huxley to lunch. She asked Gunther how he would deal with the military leaders who were threatening the Spanish government. Gunther replied that fascism called for extraordinary measures. He wouldn't permit free speech for those who would use it to destroy a democratically elected government. He added he would outlaw fascist uniforms and if necessary, after a fair trial, shoot a few plotters. Although both Thomas and Huxley were committed anti-fascists, they were both shocked by Gunther's strong views. (69)

General Emilio Mola issued his proclamation of revolt in Navarre on 19th July, 1936. General Franco, commander of the Army of Africa, joined the revolt and began to conquer southern Spain. This was followed by mass executions. Antony Beevor, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1982), has pointed out: "The local purge committees, usually composed of prominent right-wing citizens like the most prominent local landowner, the senior civil guard officer, a Falangist and, often, the priest... The committees inevitably inspired in neutrals a great fear of denunciation. All known or suspected liberals, freemasons and left-wingers were hauled in front of them... Their wrists were tied behind their backs with cord or wire before they were taken off for execution." (70)

John Gunther had been warning about the growth of fascism in Europe and the threat that posed to democracy, of course sympathized with the anti-fascist Popular Front government. As he said in Inside Europe: "On Saturday, July 18, 1936, civil war broke out in Spain. A clique of predatory and 'nationalist' minded military chieftains rose against the legally and democratically elected government of Spain, and turned the peninsula into a shambles. What began as a military coup d'etat developed into a conflict of ideologies. The Germans and Italians helped the Spanish Fascists; the Russians - later and much less intensively - helped the democratic loyalists." (71)

The Spanish Civil War brought John Gunther into conflict with his old friend, Hubert Knickerbocker. According to Paul Preston Knickerbocker's "articles in the Hearst press chain during the early months of the war, had done much for the Francoist cause". (72) Gunther thought these articles were "awful" as he believed that the Republican Army was fighting for democracy. He had heard first-hand reports of Franco's massacre of thousands of Republicans in the town of Badajoz and he considered Knickerbocker's stories of atrocities was "straight out of Hearst's playbook." (73)

John Gunther believed that the United States should become involved in the Spanish Civil War. He agreed with Archibald MacLeish that the war was a "political battlefield between democracy and reaction". In June 1938 he and Frances Fineman Gunther attended the League of American Writers' Congress at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Speakers included Donald Ogden Stewart, Earl Browder, Ernest Hemingway and Joris Ivens. Hemingway ended his seven-minute talk with an eloquent reminder about the writer's duty to "write truly" about war. (74)

Second World War

Cass Canfield was so pleased with the sales of Inside Europe that he commissioned Inside Asia. After a long tour of the region the manuscript was delivered to Canfield in April 1939. It was published two months later. The New York Times reviewer claimed that the book provided a "vivid panorama". (75) The New Yorker praised the book as "a corker" and added that it was "the plain duty of all anti-parish-pump citizens to ship east of Suez at once with John Gunther as their dragoman". (76) Time Magazine was more restrained in its review describing the book as "lively, gossipy, not too profound but interesting encyclopedia of present-day Asia." (77) The book received a hostile reception in Britain with several reviewers complaining about his "anti-British Empire sentiments". (78)

On the outbreak of the Second World War Gunther was interviewed by Walter Winchell, who at the time was arguing in favour of United States intervention against Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. Gunther told a reporter from the Miami Herald: "I would be the greatest isolationist in the country, if isolation were possible, but it isn't. We have to negotiate with these dictators, and to do that we have to have some shoulders and muscles to show that we have to be listened to." (79)

As Gunther was one of the leading figures arguing for intervention, was invited to London and on 13th September 1939, Winston Churchill, who had recently entered the government as First Lord of the Admiralty, agreed to an interview. Gunther later recalled: "Churchill... looked like an extraordinary kewpie doll made of iron and shiny pink leather. I noticed that his powerful body rose atop thin legs." Churchill told Gunther that American aid would be vital since the war promised to be long and bloody. (80)

Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin, Herbert Morrison, Leo Amery, Neville Chamberlain,

Arthur Greenwood, Lord Halifax, Duff Cooper and Anthony Eden.

In the autumn of 1941 he moved to London where he resumed his affair with Lee Miller, who had been photographing the Blitz for Vogue Magazine. He interviewed Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, Ernest Bevin, Charles de Gaulle and Juan Negrin, He also met up with old friends, Aneurin Bevan, Harold Nicholson, Rebecca West and Edward Murrow. They all asked Gunther the same question, "Were the Americans going to be in - or out?" (81)

John Gunther found living in London exciting. He wrote in his diary the sense of collective purpose was infectious. In the cinemas, British audiences cheered the Red Army louder than they did their own, and to his surprise, Joseph Stalin got more applause than Churchill. In British factories, workers were producing at top speed, they told him, for the defence of their Russian comrades. (82)

Divorce and Marriage

Gunther was now living apart from his wife Frances Fineman Gunther, He also had long relationships with actress Miriam Hopkins and journalist Clare Boothe Luce, unhappily married to Henry Luce, the owner of Time and Life magazines. He was also a regular at Polly Adler's midtown brothel. According to Deborah Cohen: "John kept lists of girls and sexual ventures the way he'd once enumerated the varieties of battleships or epochal moments in history... Eleven orgasms in the last eight days, he wrote down." (83)

John and Frances Gunther were divorced in March 1944. The New York Times reported that "John Gunther, author and foreign correspondent, obtained a divorce today from Frances Gunther. He charged that she deserted him in 1941. Judge George E. Marshall awarded to Mrs. Gunther custody of their child, John Jr. 15, together with $200 a month for his support and $600 monthly allowance." (84)

In the early months of 1946 Johnny Gunther became seriously ill. At first they thought he was suffering from polio. Later it was discovered that he had a tumor pressing on Johnny's right optic nerve. On 29th April, 16 year-old Johnny went into the operating room for six hours of exploratory surgery. The doctor found a tumor the size of an orange growing in the right occipital parietal lobe but was only able to remove half of it. (85)

The doctor left the boy's skull open, covering the incision in the bone with a bandaged flap of scalp. The technique was intended to give the tumor room to bulge outwards without exerting killing pressure on the rest of Johnny's brain. John Gunther wrote: "All that goes into a brain - the goodness, the wit, the sum total of enchantment in a personality, the very will, indeed the ego itself - was being killed inexorably, remorselessly, by an evil growth." (86)

On 30th June, 1947, Johnny suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. The tumor had eroded a blood vessel inside his head. "John and Frances were alone in the room with Johnny when he died that night. The doctors and nurses were all tending to an emergency elsewhere when Johnny suddenly began to fight for breath. He gasped, and trembled. Then he was still. Johnny's suffering had ended." (87)

A few years previously, John Gunther became romantically involved with Jane Perry, the first wife of explorer, author, and broadcaster John Vandercook. After her divorce she became an editor at Duell, Sloan & Pearce, publishers. They were married in Chicago on 5th March, 1948. Jane traveled with him extensively and contributed to and helped edit his many books. (88)

Inside USA

Under pressure from his publisher, Cass Canfield, John Gunter agreed to write a book about the United States. Gunter told Canfield it was going to be about democracy. He argued that of the three great ideological systems that had battled it out in the 1920s and 1930s, only two were still standing: democracy and communism. If it was indeed going to be an "American Century", as the publisher Henry Luce had urged, what sort of democracy were Americans living in? What kind did they want? (89)

Gunther interviewed most of the most influential figures including President Harry S. Truman. However, J. Edgar Hoover refused to be interviewed. Hoover wrote on the telegram sent by Gunther: "I am not keen about it as Gunther is far, far left of center." (90) The FBI had been keeping a close watch on Gunther since 1937 when it was reported that he was a supporter of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, the American volunteers who had gone to Spain to fight the fascists. (91)

Gunther raised an important question in the book: "On the one hand, there was the indisputable fact that America had, in a matter of months, produced the world's most formidable war machine. On the other hand, there was the manifest failure of national planning, evident in shortages of basics such as housing and food. Any pronouncement one wanted to make about the finest public education in the world? What about the 37 per cent of children in Kentucky who didn't even finish elementary school?" (92)

Harper & Brothers printed half a million copies of Inside USA (1947). It was the largest print run in the history of American publishing. (93) Robert Gottlieb argued that "John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, Inside U.S.A. - more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish." (94) The book got good reviews from the American historians, such as Arthur Schlesinger in the Atlantic Magazine (95) and Henry Steele Commager in the The New York Times (96). He also received a lot of hostile comments from local newspapers because of Gunther often critical comments about different parts of America. (97)

John Gunther died on 29th May, 1970. Albin Krebs, in his obituary in the New York Times commented: "John Gunther brought a breathless curiosity, sharp ears and eyes for the offbeat fact, a consuming vitality, a gregarious charm and a crusader's zeal to tell his readers what he thought they might not know about other people and other places." (98)

Primary Sources

(1) John Gunther, Inside Europe (1936)

This book is written from a definite point of view. It is that the accidents of personality play a great role in history. As Bertrand Russell says, the Russian revolution might not have occurred without Lenin, and modern European development would have been very difficult if Bismarck had died as a child. The personality of Karl Marx himself has powerfully influenced the economic interpretation of history. Important political, religious, demographic, nationalist, as well as economic factors are not, I believe, neglected in this book. But its main trend is personal.

The fact may be an outrage to reason, but it cannot be denied: unresolved personal conflicts in the lives of various European politicians may contribute to the collapse of our civilisation. This is the age of great dictatorial leaders; millions depend for life or death on the will of Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin. Never have politics been so vital and dynamic as today, and so pervasively obtrusive in non-political affairs. The politicians usurp other fields. What fictional drama can compare with the dramatic reality of Mussolini's career? What literary craftsman ever wrote history as Trotsky both wrote and made it? What books in the realm of art have had the sale or influence of Hitler's Mein Kampf?

(2) John Gunther, Inside Europe (1936)

Adolf Hitler, irrational, contradictory, complex, is an unpredictable character; therein lies his power and his menace. To millions of honest Germans he is sublime, a figure of adoration; he fills them with love, fear, and nationalist ecstasy. To many other Germans he is meager and ridiculous - a charlatan, a lucky hysteric, and a lying demagogue. What are the reasons for this paradox? What are the sources of his extraordinary power?

This paunchy, Charlie Chaplin mustached man, given to insomnia and emotionalism, who is head of the Nazi Party, commander-in-chief of the German army and navy, leader of the German nation, creator, president, and chancellor of the Third Reich, was born in Austria in 1889. He was not a German by birth. This was a highly important point inflaming his early nationalism. He developed the implacable patriotism of the frontiersman, the exile. Only an Austrian could take Germanism so seriously.

(3) Eugene J. Young, New York Times (16th February, 1936)

In the heart of every American newspaper correspondent in Europe is a great longing. It is to tell frankly all he knows. But suppressions and censorships stand in his way. He may be sure of certain things but he cannot send the full facts because they will be denied and he has no way of proving he was right. Or. in sending explosive facts, he might bring down on himself the wrath of the rulers, even bring expulsion, and so end the possibility of getting to Americans the portion of the truth he is in position to stand by. Now and then one of these correspondents finds he can break the inhibitions and speak right out. That is what Mr. Gunther has done. He has been all around Europe, using a keen newspaper brain to make his own observations and dig out facts, and has supplemented this process with the confidences of fellow craftsmen and other observers in the know. Much of what he tells might be called gossip, because he could not give proofs, but it is the gossip of hard-headed craftsmen- - including himself-who make it their business to find out what is what.

Mr. Gunther, who had been on the European staff of The Chicago Daily News for eleven years, serving in many countries. and at length becoming its correspondent in the freer atmosphere of London, prepared himself for the book by a journey of more than 5,000 miles last year. He looked into the problems of Germany. France, Spain, Central Europe. Russia and Britain, as well as those of the League of Nations. He deals broadly with politics, but most interesting are the sharp portraits he draws of some of those who are most in the public eye at present. There is Hitler: "Irrational, contradictory. complex, an unpredictable character," a "paunchy man given to insomnia and emotionalism." He "cares nothing for books, nothing for clothes, nothing for friends and nothing for food or drink. He is totally uninterested in women from a personal sexual view. He dislikes Berlin. He leaves the capital at any opportunity. "He dams profession of emotion to the bursting point, then is apt to break out in crying fits. A torrent of feminine tears compensates for the months of uneasy struggle not to give himself away. He does not enjoy too great exposure of this weakness and he tends to keep all subordinates at a distance."

There are also portraits of striking figures in "a fantastic congeries of sub-Hitlers. Hitler "deliberately chose to surround himself with bold and blustering spirits who often disagreed among themselves. He has, in fact, made a definite policy of playing one sub-leader against another." And "the rivalries between these men is formidable. That between Goering and Goebbels is the best known. That between Goebbels and Rosenberg is no less vicious. Goebbels and Schacht are far from being friends; Goering and Papen; Goebbels and Himmler: and every one dislikes Rosenberg." Goering, man of many titles and many uniforms and decorations, is picked by him to succeed Hitler. and that is called "a terrible possibility." For "his ambition as well as his vanity is enormous. He is brusque, impulsive, cruel. His ruthlessness is unthinking, spasmodic, hot-blooded." He is fat, but it is "fat atop of an immensity of muscle. He moves with the vigor of a man 100 pounds lighter. His energy is terrific."

Three dictators are compared. "Mussolini is built like a steel spring. (Stalin is a rock of sleepy granite by comparison and Hitler a blob of ectoplasm.) Mussolini's ascetic frugalism is that of a strong man who scorns indulgence because he has tasted it often and knows that it may weaken him; Hitler's that of a weak man fearful of temptation. Stalin, on the other hand, is as normal in appetite as a buffalo." Il Duce has no social life. He cares little for money. He listens to people, but seldom takes advice. "When he wishes he can make himself as inaccessible as a Tibetan Lama." And "for all his bombast and braggadocio, his intelligence is cold, analytical, deductive and intensely realistic."

Stalin the author holds to be "the most powerful single human being in the world; and one of the greatest." His qualities are summarized in: Guts. Durability. Physique. Patience. Tenacity. Concentration. Shrewdness. Cunning. Craft. Ruthlessness." He is "about as emotional as a slab of basalt. If he has nerves, they are veins in rock. Associates worship Hitler, fear Mussolini and respect Stalin; this seems to be the gist of it."

Finally there is Stanley Baldwin, "the most powerful of contemporary European democrats." He "is certainly not an 'intellectual'; neither is he strikingly clever nor energetic. He is the personification of John Bull: solid, sober, ponderous, the embodiment of substance. No one has ever seen him excited. Nothing has ever flustered him; he speaks only when speech is necessary; he is unshakable in his mild convictions. The chief personal influence on him is undoubtedly his wife, Lucy." He is criticized as lazy, as too supine, too passive. "His meekness at times has been astounding." But other critics say he is "extraordinarily sly." "When aroused he can make mincemeat of his opponents. It takes a great deal of unpleasantness to stir him to protect himself; when he does so he is irresistible."

In addition there is a shrewd assessment of the situation in France which is troubling many minds. There is a picture of the Fascist Casimir de la Rocque, chief of the Croix de Feu, who has so often threatened to follow in the footsteps of Hitler and Mussolini in the seizure of governmental power. "Three times he has had a chance to seize power; each time he muffed it." He "seems a rather pallid Fascist. He announces no concrete program. He waits. Perhaps he has waited overmuch." The most dangerous man in France is named as "little white-gloved Jean Chiappe," the Corsican who came to be commander of the Paris police but was deposed after the riots early in 1935. He is Rightist. On the Left is a rising figure in Gaston Bergery, "an exciting combination of idealist and practical politician." He is being called the "Lenin of France" because he has helped to organize the anti-capitalist movement. But: "What the Left in France needs is a Leader. Bergery is not quite the man. As an intellectual he is too limited, too vulnerable. Daladier is almost impossible and also Blum," the Socialist leader. "Thorez and Cachin, the Communist leaders, won't go down with anybody except Communists. In France the usual situation of a man looking for a job is reversed. There is a job looking for a Man."

Mr. Gunther's politics are not always sound. When he picks Goering as the successor to Hitler, if Hitler should pass out of the scene, he forgets he has already recorded that Hitler has put all power in Germany into the hands of the army. When he dismisses King Victor Emmanuel of Italy as "a decent little fellow" who "provides assurance of some sort of continuity." he passes lightly over the fact that this quiet king has held to his prerogatives, even so far as to put in command in Ethiopia Marshal Badoglio, who defeated the plot to make Mussolini emperor. But these hasty observations in no way detract from an interesting book that tells a lot of the inside truths of Europe.

(4) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

Gunther's next book was Inside Asia. When we discussed this volume in its initial stages, I ventured the observation that, while he'd spent several years in Europe, he'd never been farther east than Beirut, where lie had stayed only a few days. He replied that he thought lie could bone up on Asia - which he did. As was his habit, lie read intensively before starting to write, and talked to academic experts as well as to people in Washington before going on his trip. At one point I introduced him to Nathaniel Peffer, a Columbia professor and an authority on the Far East, and, after a long lunch during which Gunther scribbled like mad on a big yellow pad, I suggested that lie cancel his trip to Japan because it couldn't possibly provide him with more information than he had obtained from Peffer.

Gunther was one of the most vivid characters I have ever known, and one of the most indefatigable workers. He was helped enormously by his beautiful and intelligent wife Jane, an acute observer with a gift for factual accuracy.

I remember sitting at a cafe in the Piazza San Marco in Venice and noticing a lovely young woman striding toward me, followed by a tired, droopy man; they were the Gunthers. John complained bitterly at having been dragged through the Academia picture gallery lie was done in... A fortnight passed and the scene was repeated, in reverse. This time a bright-looking fellow walked briskly toward us, followed by a tired lady dragging her feet; the Gunthers again. During those two weeks they had been traveling in Yugoslavia, where John had interviewed scores of people. The explanation of the reversal in their roles was that the endless working sessions in Yugoslavia had acted on John like a shot of adrenalin, while Jane had found the experience utterly exhausting.

One of Gunther's remarkable qualities was his timing. Again and again it looked as if one of his Inside books would be hopelessly out-of-date by the time it was published, but there was a little alarm clock tucked away somewhere in the back of John's head which never seemed to fail him. He started Inside Europe just as Hitler was emerging as a dominant figure; he began Inside Africa when the nations of that continent were in the process of breaking away from colonization. An amazing man.

(5) Albin Krebs, New York Times (May 30, 1970)

John Gunther, journalist and author of the bestselling "Inside" books, died yesterday at the Harkness Pavilion of the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center after a brief illness. He was 68 years old and lived at 1 East End Avenue.

To the task of writing "Inside Europe," "Inside Russia," "Inside Africa" and all the other "Inside" books that brought him considerable fame and respectable fortune, John Gunther brought a breathless curiosity, sharp ears and eyes for the offbeat fact, a consuming vitality, a gregarious charm and a crusader's zeal to tell his readers what he thought they might not know about other people and other places.

For more than 30 years, Mr. Gunther was looked to by stay-at-home public for his lively, informed descriptions of the world at large. He traveled more miles, crossed more borders, interviewed more states men, wrote more books and sold more copies than any other single journalist of his time. At least 15 of his books were translated into more than 90 languages.

Although his books were enormously popular - by 1969 more than 3.5 million copies had been sold - Mr. Gunther's critics sometimes dubbed him "the master of the once-over-lightly," "the Book-of-the-Month Club's Marco Polo" and "a Jonah among journalists." To the critics' charges that his books were too slick and superficial, Mr. Gunther could reply with candor, "They're fun to write, and people like them, but they indeed are superficial."

In an interview for this article in 1969, Mr. Gunther said: "I suppose that I write, basically, for myself, to satisfy my own sometimes peculiar curiosities. In a way, my work has been an exercise in self-education at the expense of the public. But I think I'm a pretty average person, and I have worked from the assumption that if something interests me it will probably interest the casual reader too. I have tried not to underestimate the reader's intelligence nor, at the same time, overestimate what he knows."

Mr. Gunther's admirers were grateful for his grasp of sheer scope, the enthusiasm apparent in his reporting and his gift for popularizing remote places by describing them bluntly and with feeling. By noting a seemingly small detail, he could bring a place, a people, into sharp focus for his readers....

The making of the "Inside" books was phenomenally hard work, and Mr. Gunther did almost all of it himself. For "Inside U.S.A.," Mr. Gunther spent 13 months crisscrossing the nation and 14 actually writing the book. Visiting more than 300 towns and cities, he interviewed 2 to 20 people a day, and in all took more than a million words of notes.

The logistics for "Inside Russia Today" were equally impressive: six months of reading books, digests of Soviet newspapers and thousands of newspaper clippings; two weeks of briefings in Washington by Soviet watchers in the State Department and two more weeks of the same in London; 50 days (all the Russians would allow him) in the Soviet Union, where he interviewed dozens of officials, visited mental institutions and collective farms and coal mines, and covered remote Russian Asia by plane and steamer. The actual writing of the book took 14 months. Careful as he was, Mr. Gunther couldn't get everywhere and learn everything, and inevitably he made errors in fact (such as a reference in "Inside Russia Today" to a non-existent 25 kopek piece) and judgment (his verdict, in "Inside U.S.A.," that Earl Warren, then Governor of California, "will never set the world on fire or even make it smoke").

Although Mr. Gunther earned millions of dollars over the years, he was constantly strapped. This was partly due to the fact that he paid up to half of his own expenses on his globe-girdling jaunts, but per haps more important, he told an interviewer, "I've eaten every book by the time it's published."

Mr. Gunther and his first wife, the former Frances Fineman, had a daughter, Judy, who died in 1929 at the age of four months. In April, 1946, they were told that their son, Johnny, had a malignant brain tumor. Although they had been divorced two years earlier, John and Frances Gunther fought side by side to save their son's life. Fifteen months later, however, Johnny, an unusually bright and brave boy, died at the age of 17.

As an emotional catharsis, Mr. Gunther wrote a moving private memoir of the battle the Gunthers - father, mother and son - fought against death. The tender, terrifying account of the ordeal so impressed friends that they urged it be published for the inspiration of families facing similar tragedy. The vignette, "Death Be Not Proud," the profits from which went to children's cancer research, was probably Mr. Gunther's most vividly memorable work.

Mr. Gunther was in ill health during the last few years, but he continued his grueling grind of travel and writing. On his trips he was accompanied by his second wife, the former Jane Perry Vandercook (they adopted a son, Nicholas). In 1969, "Twelve Cities," based on recent trips to 12 capitals, was briefly on the bestseller lists.

(6) Robert Gottlieb, New York Times (June 26, 2021)

Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, Inside U.S.A. - more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies - the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers - plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman's Peace of Mind and the Information Please Almanac. It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther's first great success, Inside Europe, published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; Inside Asia and Inside Latin America followed, with comparable success - all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be Inside Africa and Inside Russia Today, yet to come. His Roosevelt in Retrospect (1950) is one of the best political biographies I've ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like Inside U.S.A., it is out of print - please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear.

Gunther was born in Chicago in 1901, went to the University of Chicago and then on to The Chicago Daily News, where in 1924 he scored with an eyewitness report on the Teapot Dome - not the tremendous scandal but the actual place (in Wyoming), to which no previous journalist had bothered to go. ("Teapot Dome has no resemblance whatever to a teapot or a dome.") By the next year he was in London for The Daily News, and soon was darting around Europe on missions to Berlin, Moscow, Rome, Paris, Poland, Spain, the Balkans and Scandinavia, before being given the Vienna bureau. It was as if he had been in training for "Inside Europe."

He managed to find time to marry Frances Fineman, also a journalist, with whom he shared a very long and very tortured marriage, not helped by either her obsessive attachment to Jawaharlal Nehru or John's wandering eye. (One woman on whom his eye had rested was Rebecca West, who referred to him in a letter to a friend as that "young and massive Adonis with curly blond hair.") But his most important, if platonic, relationship with a woman was with the famous journalist Dorothy Thompson - hers was the other clarion voice alerting America to the perils to democracy, to civilization, from Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin. The close bond between these two "competitors" never slackened until Thompson's death, in 1961.

The worst thing that happened to John Gunther was the death, at the age of 17, of his beloved son, Johnny - about which, in 1949, he wrote Death Be Not Proud, which still sells thousands of copies every year. The best thing that ever happened to him, apart from his deeply fulfilling career, was his second marriage. Jane Perry - young, pretty, highly educated - became an essential partner in his work until his death, in 1970. (She outlived him by 50 years, dying in 2020 at the age of 103.)

What was Gunther like? It's a fair question to ask about him, since what people were like was always at the heart of his reporting. ("I had little basic interest in politics," he wrote in A Fragment of Autobiography, "a fault which besets me to this day, but I was ravenously interested in human beings.") Obviously he was a fanatical worker - his notes for Inside U.S.A. approached a million words - although he chose to believe that he was lazy at heart. ("I am not efficient at all, and anybody close to me knows how physically lazy and self-indulgent I am. I waste a preposterous amount of time sitting inert like a blob of protoplasm.") He loved to laugh. He loved good wine, good food, good nightclubs. He had countless friends - from kings to bartenders, as he liked to say. He was never pompous, never self-promoting, never stuck-up. He made huge amounts of money and spent it all - often before it was actually in hand. And he was unfailingly generous. No wonder everybody liked him.

As for his writing, he would have been embarrassed at the notion that he had a "style." What he did have was a voice - fluent, personal, casual, snappy. His opinions came across - he was a pro-New Deal liberal - though not through editorializing. He was a reporter - probably the best America ever had. He came, he saw, he wrote. When recently I mentioned to Bob Caro that I was writing about Inside U.S.A., he lit up. "What a book! When I was writing ‘Master of the Senate' I had it on my desk next to my typewriter, and whenever I needed to check on someone or something, all I had to do was open it up. And the sense it conveys about America in the postwar 1940s! There's just nothing like it!"

One of the things that makes it so alive is Gunther's curiosity about his own country; he knew Latin America, he knew Europe, he knew Asia, but he didn't know America. "The United States, like a cobra, lay before me, seductive, terrifying and immense," he wrote. Inside U.S.A. was the hardest task I ever undertook." He was yet again an outsider, looking in. "Not only was I trying to write for the man from Mars; I was one."

Gunther begins his discovery of America in California - "the most spectacular and most diversified American state, California so ripe, golden, yeasty, churning in flux.… at once demented and very sane, adolescent and mature" - and he proceeds around the country, state by state, until he arrives in Arizona, next door to where he began. Sometimes he devotes an entire chapter to a single person - the perpetual presidential candidate-to-be Harold Stassen; the great industrialist Henry Kaiser; New York's colorful (to say the least) Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who is probably best remembered for having, during a strike of newspaper deliverers, read "the funnies" aloud on the radio so as not to disappoint the city's kids.

The La Guardia chapter is not, however, about the mayor's adorableness; it's an extraordinary tour de force in which Gunther shadows his subject for more than 10 hours, mostly spent perched near the corner of his desk recording the mayor's activities almost minute-by-minute and revealing a staggering degree of vigor, administrative genius and robust thinking. "Meeting of the Mayor's Committee on Race and Religion … points discussed: pushcart peddlers and a new Harlem market; problems involving pickles in fancy glasses; Coney Island; what's the best municipal library in this country; housing problems for families who live on less than $2,500 a year; savings bank mortgages and their relation to housing projects; discrimination against Negroes in employment; the numbers racket; origin of Irish and Italian gangs; how to build a proper community spirit." One highlight: "10:28. … I asked him about the big trough of files. ‘I'll tell you a little story. Files are the curse of modern civilization. I had a young secretary once. Just out of school. I told her, "If you can keep these files straight, I'll marry you." She did, and so I married her.'"

And then there's an inspiring chapter about the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority: the fierce battle between the private sellers of electricity and the determination of President Roosevelt, in his very first months in office, to tame the Tennessee River for the benefit of the citizens of seven states � possibly Roosevelt's greatest domestic achievement. "A final common denominator about T.V.A. is the simple tablet that each of its units wears: BUILT FOR THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES."

In counterpoint to these extended essays and profiles are hundreds and hundreds of short takes, seemingly chosen at random, culled by Gunther's eagle eye as he scoured the country. Here are mundane conversations overheard; meetings with governors and senators; quotes from lunatic right-wing newspapers; the uninhibited talk of millionaires and sharecroppers. Here, we come to believe, is America: "Los Angeles is Iowa with palms." "Everything goes in Los Angeles, so it may be thought; but here are some things forbidden by city ordinance, as itemized by H. L. Mencken in ‘Americana': Shooting rabbits from streetcars. Throwing snuff or giving it to a child under 16. Bathing two babies in a single bathtub at one time. Making pickles in any downtown district. Selling snakes on the streets."

"The Pacific Coast is the end of the line in the westward trek across the continent. The hills around Ventura, let us say, are the last stop; California is stuck with so many crackpots if only because they can't go any further." xxx Example of the prose style of Hiram Johnson, then running (successfully) for governor of California, attacking Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of The Los Angeles Times: "He sits there in senile dementia with a gangrene heart and rotting brain, grimacing at every reform, chattering impotently at all things that are decent, frothing, fuming, violently gibbering, going down to his grave in snarling infamy … disgraceful, depraved … and putrescent."

The "ghost town" Virginia City, in Nevada, is a "fragrant tomb." "Never have I seen such deadness. Not a cat walks. The shops are mostly boarded up, the windows black and cracked, the frame buildings are scalloped, bulging, splintered; C Street droops like a cripple, and the sidewalks are still wooden planks; the telephone exchange, located in a stationery shop, is operated by a blind lady who had read my books in Braille."

"Few people, unless they read the Congressional Record carefully, realize what a good congresswoman Mrs. [Clare Boothe] Luce was; she was at a disadvantage most of the time in that she became a victim of her own reputation, versatility and beauty; her long hours of conscientious work never got in the papers; the wisecracks did."

How to explain Thomas Dewey's unpopularity? "Most Americans like courage in politics; they admire occasional magnificent recklessness. Dewey seldom goes out on a limb by taking a personal position which may be unpopular on an issue not yet joined; every step is carefully calculated and prepared; … he will never try to steal second base unless the pitcher breaks a leg."

And then there is America's future to ponder. "There is no valid reason why the American people cannot work out an evolution in which freedom and security are combined," Gunther concludes. "In a curious way it is earlier, not later, than we think. The fact that a third of the nation is ill-housed and ill-fed is, in simple fact, not so much a dishonor as a challenge."

What Americans have to do is enlarge the dimensions of the democratic process. This country is, I once heard it put, absolutely ‘lousy with greatness' � with not only the greatest responsibilities but with the greatest opportunities ever known to man." Finally, Inside U.S.A . is an unintentional account of a man falling in love with his crazy and wonderful country.