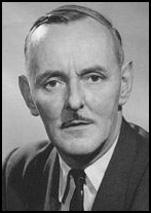

Eric Maschwitz

Eric Maschwitz, the son of a Lithuanian Jew, was born in Edgbaston, Birmingham, on 10th June 1901. He recalled in his autobiography, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957): "Papa was twenty years older than my pretty Australian mother and was already forty-one when I was born. He was... an Olympian figure who kissed us night and morning, and continued to do so until we were quite grown up. Papa was a truly delightful man, a gourmet, a traveller, a prolific reader, a good tennis player, an indifferent golfer and an accomplished host. He had a splendid cellar, smoked Upmann cigars, collected stamps, could chatter in seven languages, and loved every moment of his long; up-and-down existence."

Maschwitz's father was from Lithuania and ran a business supplying toilet fixtures. In 1909 Eric was sent away to Arden House boarding school in Henley-in-Arden. He later recalled: "For the first year at Arden House I cried a good deal under my pillow at night. I was very lonely. In those days parents were not encouraged to visit their offspring at school, even supposing such an extraordinary idea should have happened to enter their heads. They arrived only once a year, on our birthdays, or to watch us high-jumping and throwing cricket balls in the School Sports."

In 1915 Maschwitz went to Repton School: "The Repton to which I came, a small spectacled boy with no prowess at games, though some at scholarship, lay under the shadow of war. The senior boys left to join up, returned as visitors in uniform, and were often not heard of again until their names were read out among the obituary notices in Chapel. There was a great deal of drilling with the O.T.C. and the food became increasingly sparse and monotonous.... Our diet from 1915 onwards included a distressing repetition of vegetable pie and porridge plastered with glucose.... If it had not been for an occasional cake or pork-pie in our parcels from home I think we might well have starved!"

The headmaster was a young clergyman Geoffrey Fisher who had replaced William Temple. "His predecessor had been the Reverend William Temple, also destined for the See of Canterbury... Temple... though kindly and popular, was no disciplinarian so that Fisher had been faced in 1914 with the problem of pulling the school together.... The headmaster, housemasters, prefects, even the heads of studies, were allowed to enforce discipline with the cane. During my first year at the Hall I was beaten by somebody regularly once or twice a week, usually upon the flimsiest of excuses. In spite of this I came through my schooldays without any particular complexes, inhibitions or persecution mania. There is something to be said for corporal punishment; it can be simply and rapidly administered and makes the recipient rather ashamed of himself. I am not, however, recommending an orgy of flagellation such as greeted me upon my arrival at school when the head of our house gave the whole body of eighty boys (prefects excepted) 'four apiece' because nobody would own up to having broken a window!"

Maschwitz was greatly influenced by two of his masters, Victor Gollancz and David Somervell: "Gollancz, who had served in the early years of the war as a subaltern in the Northumberland Fusiliers, came to Repton in 1917 to teach Classics. He and Somervell, both men of great intelligence and liberal ideas, were responsible for the formation of a Civics Class at which they and others lectured on sociology and world affairs and there was much lively discussion. The world was changing; Lenin and Trotsky had swept away the Czar, the break-up of the old European order had began."

In 1919 Maschwitz was awarded a Modern Languages scholarship at Gonville & Caius College. He joined the Cambridge University theatre group and played the role of a woman, Vittoria Corombona, in The White Devil. He was also a member of the Footlights Dramatic Club as well as contributing poems to the various undergraduate magazines. Very keen to become a writer, Maschwitz wrote a novel, "a flagrant pastiche of my literary hero" Compton Mackenzie. This was eventually published under the title, The Passionate Clowns.

After leaving university Maschwitz became an assistant stage-manager at His Majesty's Theatre in London. He was a regular visitor to the Café Royal where he became friends with Frank Harris, Augustus John, Christopher Nevinson, William Orpen, Mark Gertler, Michael Arlen, Ronald Firbank and James Agate. After meeting Michael Joseph he became assistant-editor at a publishing company. Maschwitz obtained a literary agent, Nancy Pearn, and had a novelette entitled The Little Lady , serialised in the Daily Mirror.

Eric Maschwitz became romantically involved with Michael Joseph's wife, the actress, Hermione Gingold. They moved to the Porquerolles, an island off the Côte d'Azur. Over the next three months Maschwitz wrote a novel, A Taste of Honey. The book sold well and was able to rent a flat in Earls Court Road. However, the follow-up, Angry Dust, was a complete failure.

In 1926 Rebecca West introduced Maschwitz to the American journalist, John Gunther. He described Maschwitz as being: "Tall, 25, black hair falling over his forehead, tortoise shell glasses". The two men became close friends and decided to go on holiday together in Paris. Eric's wife, the actress, Hermione Gingold, also joined them on their visit. However, after a week Maschwitz ran out of money and was forced to return to London.

During the General Strike Maschwitz enlisted as a Special Constable. He later recalled "I enlisted more to fill the empty days with a little adventure than with an idea of opposing the workers of the world!" A week after the strike ended Maschwitz met an old friend, Lance Sieveking, who had just started work for the British Broadcasting Company. Sieveking introduced him to his boss who employed him on the yearly salary of £300.

Maschwitz got on well with the Director-General John Reith: "Much as has been said and written in criticism of the BBC's first director-general, now Lord Reith. Six-feet-six in height, his dour handsome face scarred like that of a villain in a melodrama, he was a strange shepherd for such a mixed, bohemian flock... He had our respect (even if we made grudging fun of him in private); he was scrupulously just and, if you were not afraid of him, intensely human under his somewhat frightening exterior. He was always kind to me and I admire him still to the point of hero-worship."

In October 1927 Maschwitz married Hermione Gingold. Maschwitz later recalled: "The bride, who carried for her bouquet, a penny bunch of Parma violets, wept bitterly throughout the ceremony. My dear father, who had with impeccable generosity forgiven me my various misdemeanours, behaved most beautifully to us both, though I detected eyebrows raised between my mamma and himself as we accompanied them along the muddy lane that led to our first abode. At the studio we were greeted by Hermione's three cats, each with a cod's head on a tin plate, the rain was dripping through the glass roof and so the wedding breakfast, although a friendly enough affair, was not what might have been termed a riotous success!"

Maschwitz was involved in the BBC radio drama unit. This included writing the script for Carnival, a novel written by Compton Mackenzie. In his autobiography, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957) he admitted: "I received no payment for it, nor indeed for any other of the dozens of scripts, long and short, which I wrote for broadcasting; in those days the BBC staff were expected to writer for nothing!".

Maschwitz's friend, Cedric Belfrage, was the film critic of The Daily Express. When Lord Beaverbrook sent Belfrage to Hollywood, Maschwitz went with him for an extended holiday. "In Hollywood Cedric and I settled into a small apartment at the Roosevelt Hotel. As representative of a leading London newspaper he had the entree to all the studios, then very active in the first flush of the talking picture. He was kind enough to take me with him on his rounds and I found myself, as wide-eyed as any juvenile movie-fan, face to face with the gods and goddesses of the screen. I met most of them and remember few of them - except for Sylvia Sidney with her quick wit and almost Oriental beauty and Douglas Fairbanks Junior, who remains my friend to this day."

Belfrage introduced Maschwitz to Upton Sinclair: "An old friend of Cedric Belfrage's was Upton Sinclair, the novelist at that time still active in the Socialist cause. Sinclair lived then in a wooden house in Pasadena so entangled in jasmine that, when we called to visit him, the perfume was almost stifling. A frail, yet dynamic man in the mid-fifties he talked fascinatingly for hours, communicating at intervals with his wife, who was upstairs in bed with a chill, by means of a police-dog to whose collar he tied notes. When we were about to leave, he said: 'Well, I guess you boys would like a drink'; we accepted and were immediately regaled with two glasses of water! I took away with me an autographed copy of his latest novel The Flivver King which was an expose of the Henry Ford Empire."

In 1933 Maschwitz was placed in charge of radio "variety shows which consisted of dance music, vaudeville, operetta, light concerts and feature programmes". His most important innovation was the new programme, In Town Tonight: "I devised to provide a shop window for any topical feature that might bob up too late to be included in the Radio Times... It was my idea, with In Town Tonight, to collect together a number of such last-minute items at what was then considered to be one of the peak hours of the week, namely 6.30 p.m. on Saturday." Its theme music was the Knightsbridge March by Eric Coates.

Maschwitz was introduced to Jack Strachey, a composer of music. They decided to write songs together. One of their first attempts in 1936 was These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You). It has been claimed that the lyrics by Maschwitz was based on his love affair with the Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong. The song became a standard and writing in 1957 he claimed that he made £40,000 from the song.

Maschwitz also joined forces with George Posford to write the musical play, Balalaika. It opened in London at the Adelphi Theatre on 22nd December 1936. It was a great success and ran for 569 performances, after which it was taken out on a long tour by Tom Arnold. In the spring of 1937, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, offered him £25,000 for the play.

Maschwitz went out to Hollywood to discuss the project. After an agreement was reached he was paid £350 a week to write screen treatments of the musical play, The New Moon, and the novel, The Red Lacquer. He became friends with several stars including, Robert Benchley, Margot Grahame, Sylvia Sidney, Douglas Fairbanks, Greer Garson, George Sanders and Hedy Lamarr.

After six months Maschwitz became disillusioned with the way the system worked: "That I had not been happy in Hollywood was not Hollywood's fault. It had given me six months of luxurious living in an Elysian climate, and the friendship of dear people whom I have never forgotten. And if I were invited to work there again today I would go west with gladness, for with age comes philosophy. In 1937 I had been a small cog in a titanic spendthrift machine, a minnow among the whales (and a few sharks) in the aquarium of the New Writers' Block. I had, I fondly think, no personal vanity, I only wanted to be allowed to work. The waste of money upon my unused services irked the peasant element in my make-up."

On his return to London he attempted to write a follow-up success to Balalaika. "The first night of Paprika, when it came, was a disastrous failure. It was at the time of Munich; from outside the theatre the brass band of a Peace Procession vied audibly with the orchestra within; political fanatics invaded the dressing-rooms flourishing pamphlets, thereby so frightening the child actors in the cast that they burst into tears and had to be pushed, still weeping, onto the stage. Towards the end of the piece an unknown actress, afterwards famous as Carol Lynne, sang a simple Victorian ballad and for the first time the audience broke into loud applause. In the wings that wise old trouper Helen Have took me by the arm. "Hear that, young man?" she said. "If that's all they can find to go mad about, you've got a flop! " And she was right. On the second night of Paprika there were more people (78) on the stage, than in the auditorium (53); after thirteen unhappy performances the play closed."

In 1939 Maschwitz wrote A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, with Manning Sherwin. "The title, stolen from the Michael Arden story, led easily to a pleasantly fantastic lyric. The song had its first performance in a local bistro with Manning and the resident saxophone-player belting out the melody while I, glass in hand, obliged with the words. Nobody seemed to be particularly impressed." The song became a great success when it was sung by Judy Campbell, in the show, New Faces .

The movie, Balalaika, appeared in 1939. Produced by Lawrence Weingarten and directed by Reinhold Schunzel, it starred Nelson Eddy and Ilona Massey. Maschwitz was disappointed that only the musical's title song At the Balalaika , with altered lyrics, was used in the film. Instead, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had music director Herbert Stothart adapt materials it already owned or were otherwise available, or write original material as needed.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Maschwitz was recruited by Special Operations Executive (SOE): "I was sent away with others, to undergo a course of training in Explosives and Demolition....The course was held at a secret establishment in Hertfordshire. When we arrived there I observed with some misgivings that the Chief Instructor had had part of his jaw blown away, while his Sergeant Major was short of three fingers on one hand! For several days we were initiated into the mysteries of a new explosive known as plastic; it looked like sticks of children's plasticine and had the reputation of being both devastating and slightly undependable."

In 1940 Maschwitz was sent to New York City to work with the British Security Coordination (BSC) run by William Stephenson. He later admitted "I had been provided with a passport that gave my profession as Ministry of Supply. I was to be taken not as an army officer but as a former playwright on national service as a civilian." Other members of the BSC included Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, David Ogilvy, Paul Denn, Isaiah Berlin, Giles Playfair, Cedric Belfrage,Benn Levy, Noël Coward and Gilbert Highet. The CIA historian, Thomas F. Troy has argued: "BSC was not just an extension of SIS, but was in fact a service which integrated SIS, SOE, Censorship, Codes and Ciphers, Security, Communications - in fact nine secret distinct organizations. But in the Western Hemisphere Stephenson ran them all."

Maschwitz was appointed head of Station M, the phony document factory in Toronto. Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has argued that Maschwitz worked closely with Ivar Bryce: "During the summer of 1941, he (Bryce) became eager to awaken the United States to the Nazi threat in South America." It was especially important for the British Security Coordination to undermine the propaganda of the American First Committee. Bryce recalls in his autobiography, You Only Live Once (1975): "Sketching out trial maps of the possible changes, on my blotter, I came up with one showing the probable reallocation of territories that would appeal to Berlin. It was very convincing: the more I studied it the more sense it made... were a genuine German map of this kind to be discovered and publicised among... the American Firsters, what a commotion would be caused."

William Stephenson, who once argued that "nothing deceives like a document", approved the idea and the project was handed over Maschwitz. It took them only 48 hours to produce "a map, slightly travel-stained with use, but on which the Reich's chief map makers... would be prepared to swear was made by them." Stephenson now arranged for the FBI to find the map during a raid on a German safe-house on the south coast of Cuba. J. Edgar Hoover handed the map over to William Donovan. His executive assistant, James R. Murphy, delivered the map to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The historian, Thomas E. Mahl argues that "as a result of this document Congress dismantled the last of the neutrality legislation."

After the British Security Coordination had achieved its objective and the United States entered the war, Maschwitz, promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, returned to London and became one of the British officers in the Psychological Warfare Branch of SHAEF. Here he worked with William Paley and Richard Crossman. "The section to which I was attached specialised in Leaflet Warfare. The young officer who was our liaison with the Flying Fortress squadron which was to drop our paper ammunition upon the enemy, had invented a leaflet bomb a cardboard container which could be disintegrated at any distance from the ground by means of a time-fuse."

One of Maschwitz's most successful propaganda projects was the publication of a German newspaper Nachtrichen fur die Truppe . Maschwitz explained in his autobiography, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957): "It was brilliantly devised and edited by a famous newspaper correspondent who was at the same time managing a bogus Germany Army Radio Station situated outside London. The interrogation of prisoners revealed that a large proportion of the enemy's troops believed that both the newspaper and the radio programme emanated from their own side of the line!"

After the war Maschwitz worked on several musical projects including Starlight Roof with Vic Oliver, Fred Emney, Patricia Kirkwood and Julie Andrews. "As collaborator in the dialogue I had Matt Brooks, a comedy-writer from Broadway with an encyclopaedic knowledge of his business. Matt's most hilarious sketch for Starlight Roof concerned the misfortunes of Vic Oliver, newly wed to a famous striptease dancer (Barbara Perry), who found out on his honeymoon night that his bride could only remove her clothes to music! Not a very refined idea perhaps, but I never heard an audience laugh longer or more loudly. Everybody enjoyed it except Barbara; she was a girl of nice principles and used to blush visibly as she stripped! An 'unknown' in the cast of our show was the phenomenal child soprano, Julie Andrews. Dressed in a gym frock and school hat, she came out of the audience and, accompanied on the piano by Vic Oliver, sang an operatic aria in a coloratura that would not have disgraced Lily Pons."

In 1949 Maschwitz resumed his partnership with Jack Strachey. However, their musical play was not popular with post-war audiences. In 1951 he teamed up with Emile Littler and their first production, Zip Goes a Million!, featured George Formby. It was an immediate success but their follow-up productions, Thirteen for Dinner , Ghost Train and Romance in Candlelight , failed at the box office and the two men decided to break up their partnership.

Maschwitz now joined up with Hyman Kraft to write Summer Song that was eventually produced in 1955. "For the musical score of Summer Song we selected melodies from the music of Dvorak, including of course the New World symphony.... I have never enjoyed lyric writing so much; setting verses to such music was a happy change from writing in syncopation. Not that it was a light task; certain of the Czech folk-dance rhythms were difficult to match with words... The completion of Summer Song took myself and my partners two years in the course of which we produced seven different versions of the script and I wrote lyrics for eight more songs that were eventually used." Unfortunately for Maschwitz the production was not a success.

In 1957 Maschwitz published his autobiography, No Chip on My Shoulder. It concluded with a brief analysis of himself: "A man aged 55, height 6 feet 2 inches, weight 173 lbs, hair still plentiful but inclined increasingly to grey, eyes brown and now rather short-sighted, teeth woefully incomplete... A man who has lately lived too much indoors, smoked far too many cigarettes, drunk perhaps a little too much whisky, yet who still has a voracious appetite, particularly for bread, reacts suitably to the contiguity of an attractive woman, can sleep his eight hours, without stirring the bed-clothes, like an an exhausted child.... What of his intellectual capacity? This is no blazing intellect; its owner thinks too quickly and words come to him too easily for that. He has read enormously and learned too little from books; felt too much and thought too little; his reactions are quick and too often superficial. He cannot fathom the game of chess. Has no technical understanding of Music, never scored more than 12 per cent of marks in a paper on Mathematics. And yet he is not without a certain practical sense, has spent a dozen years of his life as a business executive responsible for the control of a large staff and the spending of a great deal of other people's money."

Eric Maschwitz died on 27th October 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

I was born on Monday, 10th June, 1901, into a world filled with aunts and butterflies. Birth control being what it is to-day, no child of the future is likely to have as many aunts nor, thanks to modern methods of crop-spraying, will he ever see as many butterflies. The aunts crowded round my little cradle while beyond the windows, in the garden of my father's house in Edgbaston, that highly respectable suburb of Birmingham, Red Admirals and Tortoiseshells, Peacocks and Cabbage Whites performed a series of divertissements among the calceolarias in honour of my birth.

(2) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

Papa was twenty years older than my pretty Australian mother and was already forty-one when I was born. He was more than a little shy with us; we children had none of the free-and-easy "Christian names" relationship with him that youngsters enjoy today; he was an Olympian figure who kissed us night and morning, and continued to do so until we were quite grown up. Papa was a truly delightful man, a gourmet, a traveller, a prolific reader, a good tennis player, an indifferent golfer and an accomplished host. He had a splendid cellar, smoked Upmann cigars, collected stamps, could chatter in seven languages, and loved every moment of his long; up-and-down existence. He had a positive passion for tidiness and precision and could not bear to see anything "out of the straight" (as a young man he had been arrested in the Louvre for leaning over a barrier and attempting to straighten a crookedly hung Tintoretto!). He read aloud beautifully and had an endless string of reminiscences of the days when he was young and had spent much of his time abroad. He had travelled in Japan in the 1880s when there was still no railway there and it was the custom for a visiting foreigner to engage a "wife" to sustain him on the long slow journies by rickshaw. At the Opera in Madrid he had narrowly escaped assassination at the hands of a jealous caballera at whose wife he had gazed too admiringly during the performance!

We never realised as children that the family business was largely concerned with the supply of what used to be called "sanitary pottery" (and is now known as "toilet fixtures"), though I recall the excitement when Papa built a new bathroom and installed in it the first bidet ever seen in Birmingham....

I inherited my happy disposition, along with a fairly rugged constitution, from dear Papa. Mine was a golden childhood, although we were brought up with almost Victorian simplicity; "children should be seen and not heard" was the order of the day. We never took a meal with our parents until we were eight, bedtime was early, our diet Spartan. We invented our own games and went around with troops of other children, supervised by nannies and governesses. We were really children, not little men and women. I do not think those first lessons in self-discipline and self-denial did us any harm, any more than did the rough treatment we afterwards met with at school. This was in the happy time before Child Psychology had been heard of; if you were naughty, you were punished, if you were good you went unrewarded; you were taught never to steal or sulk or be idle; nobody was interested in your "ego" or your "immortal soul". It was not difficult then to grow up happy!

We had servants and they were our good friends. How they can have been so happy, on £25 a year, and every second Wednesday afternoon off, still perplexes me, but happy they were; the big basement kitchen, where the tea-pot was never absent from the top of the massive range, echoed with their chatter and laughter as Cook interpreted from her tuppenny dream-book the significance of Emily's dream about pineapples.

(3) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

The Repton to which I came, a small spectacled boy with no prowess at games, though some at scholarship, lay under the shadow of war. The senior boys left to join up, returned as visitors in uniform, and were often not heard of again until their names were read out among the obituary notices in Chapel. There was a great deal of drilling with the O.T.C. and the food became increasingly sparse and monotonous. In the Second World War special measures were taken for the feeding of the young (many of them had never eaten better in their lives), but our diet from 1915 onwards included a distressing repetition of vegetable pie and porridge plastered with glucose. As time went on the "grubber", as the school tuck-shop was called, ran out of chocolate bars and we learned to make sweets of our own by mixing chocolate powder with cocoa-butter. If it had not been for an occasional cake or pork-pie in our parcels from home I think we might well have starved !

Our Headmaster was a young clergyman by name Geoffrey Fisher. He had several opprobrious nicknames among the boys, but I will spare the present Archbishop of Canterbury a disclosure of them! His predecessor had been the Reverend William Temple, also destined for the See of Canterbury. "Billy", though kindly and popular, was no disciplinarian so that Fisher had been faced in 1914 with the problem of pulling the school together. "Writing lines" was the penalty for bad behaviour in class, beating for misdemeanours outside. The headmaster, housemasters, prefects, even the heads of studies, were allowed to enforce discipline with the cane. During my first year at the Hall I was beaten by somebody regularly once or twice a week, usually upon the flimsiest of excuses. In spite of this I came through my schooldays without any particular complexes, inhibitions or persecution mania. There is something to be said for corporal punishment; it can be simply and rapidly administered and makes the recipient rather ashamed of himself. I am not, however, recommending an orgy of flagellation such as greeted me upon my arrival at school when the head of our house gave the whole body of eighty boys (prefects excepted) "four apiece" because nobody would own up to having broken a window!

For his first few years at Repton Geoffrey Fisher was unpopular, then little by little we came to realise that he had a sense of humour as well as of justice. When his first son was on the way the House ran a penny sweepstake on the date of his birth (7s. 6d. was a small fortune in those days!). To celebrate the boy's arrival we were given a special supper (with poached eggs); when the headmaster said goodnight to us he added with a twinkling smile "And I believe I have to congratulate the lucky winner?". This sly remark did more to make him popular than any of his achievements in office!

The Repton masters were mostly kindly and competent. Several achieved fame outside the little world of school-Hooton for his writings on chemistry, D. C. Somervell as a historian, Victor Gollancz as a writer and publisher of books.

Gollancz, who had served in the early years of the war as a subaltern in the Northumberland Fusiliers, came to Repton in 1917 to teach Classics. He and Somervell, both men of great intelligence and liberal ideas, were responsible for the formation of a Civics Class at which they and others lectured on sociology and world affairs and there was much lively discussion. The world was changing; Lenin and Trotsky had swept away the Czar, the break-up of the old European order had began. From the Civics Class stemmed a remarkable publication, a literary and political review entitled "A Public School looks at the World" with the style and format of "The New Statesman"; contributions came from both boys and masters (including a poem by my own youthful self). The tone of this review was mildly "left wing" (although to-day it would have had an almost reactionary flavour). Conservative parents upon reading it became convinced that Repton was "going Red"; reports to the effect that Communism was rampant in the one-time capital of Mercia reached M.LS, and the purge was on! The War Office sent a stuffy Major-General to investigate the tone of the school; after sitting through a number of classes with an air of severe bewilderment he paraded the O.T.C. and addressed us on the subject of Patriotism, the Empire and the necessity of young fellers concentrating upon the job of killing the Boche! Gollancz and Somervell vanished from the scene, as many copies as could be found of "A Public School looks at the World" were destroyed, and a public school was left looking at itself with a rather shame-faced giggle. The whole episode was in its way extraordinary.

As long as I was at Repton the younger boys wore a uniform of Eton jackets, their elders tail coats, topped with white straw hats, except in the case of school prefects and the Sixth who wore speckled straws. It did not add to my personal popularity that I got into the Sixth while I was still only fifteen and was, therefore, no longer required to "fag" for anyone. "Fagging" was not a particularly arduous duty, being mainly confined to shining one's master's shoes and making toast and cocoa-plus, of course, putting up with a certain amount of chastisement if one was slow or cheeky. Between the ranks of "study-holder" and "fag" stood the "seconds" who occupied the second-best corner of a study and were neither masters nor servants. At various times my own "fags" were the Viscount Ikerrin, Dudley Joel, Everard Gates, now a Member of Parliament, and Ashley Clarke our present Ambassador in Rome!

Christopher Isherwood turned up at the Hall shortly before I left; Benn Levy, the playwright, was at the Orchard House, and at Brook House a pious-seeming choirboy named Edward Cooper who, many years later, became the accompanist-partner of Douglas Byng and came to a tragic end through falling down the stairs of a night club! Of my contemporaries I recall few others with any clarity.

(4) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

On a rainy day in the late winter "Hermione Ferdinanda" was joined in holy matrimony with "Albert Eric" at the Register Office in Marylebone; the bride, who carried for her bouquet, a penny bunch of Parma violets, wept bitterly throughout the ceremony. My dear father, who had with impeccable generosity forgiven me my various misdemeanours, behaved most beautifully to us both, though I detected eyebrows raised between my mamma and himself as we accompanied them along the muddy lane that led to our first abode. At the studio we were greeted by Hermione's three cats, each with a cod's head on a tin plate, the rain was dripping through the glass roof and so the wedding breakfast, although a friendly enough affair, was not what might have been termed a riotous success!

(5) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

No one who only knows the BBC as it is today, with its huge staff, many buildings, and air of grandmotherly efficiency, can imagine the little "village broadcasting company" into which I had been whisked by Lance Sieveking in 1926.

The British Broadcasting Company had been started in 1922 with capital provided by the leading wireless manufacturers; if their receivers were to be sold, then there must be programmes to be picked up by them. Through advertisements in the Press the Company had recruited a Director-General (Mr. J. C. W. Reith, a Glasgow engineer of formidable appearance and ambition), a Programme Director (Mr. Cecil A. Lewis, a former fighter-pilot turned playwright) and a Chief Engineer (Captain Peter Eckersley who combined with brilliant technical gifts an unquenchable enthusiasm for entertainment). Its first home had been Marconi House in Aldwych, where the studio was so small that, if we are to believe Stanton Jefferies, the Company's first Director of Music, it was necessary to broadcast with the door open in case the 'cellist should fracture his elbow!

By the time I joined the BBC the organisation had moved to Savoy Hill and the staff increased to service not only London but half a dozen provincial stations as well. No. 2, Savoy Hill, had, at one time, been a slightly risque block of flats where I had attended my first theatrical party in 1917. Though it had been cleverly adapted as a radio headquarters, it was a fairly ramshackle building nevertheless. I remember killing a rat in one of the corridors - by the simple method of flattening it with a volume of Who's Who! Office accommodation was very limited, most of us working four or five in a room...

Much as has been said and written in criticism of the BBC's first director-general, now Lord Reith. Six-feet-six in height, his dour handsome face scarred like that of a villain in a melodrama, he was a strange shepherd for such a mixed, bohemian flock. By upbringing intensely religious in the Noncomformist faith, he had under his aegis a bevy of ex-soldiers, ex-actors, ex-adventurers which a Carton de Wiart, a C. B. Cochran, even a Dartmoor prison governor might have found difficulty in controlling. But he had our respect (even if we made grudging fun of him in private); he was scrupulously just and, if you were not afraid of him, intensely human under his somewhat frightening exterior. He was always kind to me and I admire him still to the point of hero-worship. For British Broadcasting he ordained the "shape of things to come"; as, cap in hand, I wait today in the foyer of Broadcasting House, I am still moved by the sight of his name in the Latin inscription above the elevators.

(6) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

At that time my sweet Hermione was sadly disappointed in me. Who could have blamed her? What kind of husband was this, twelve hours away at the office, then down to a desk at home scribbling at radio programmes until dawn (without payment!). Since our fortunes had begun to improve we had moved from the leaky studio, first to a maisonette in Edwardes Square, thence to a house in Chelsea, finally to a flat in Adam Street off the Strand. Certainly life was more comfortable for her, but I realise now that it wasn't that sort of comfort she needed; she was having to spend far too much time alone with the fact that, although she knew in her pretty bones that there was a place for her in the theatre, nobody seemed to want to employ her. I could perhaps have done more to encourage her, given her more of my time and companionship instead of allowing myself to become a slave to broadcasting. Inevitably we had begun to drift away from each other, finally settling into separate flats in the same street. The separation distressed me, but I had not the time or the good sense to see what to do about it. It was in a mood of depression that I decided to pay a first visit to the United States.

The expedition was suggested by Cedric Belfrage to whom I had been introduced some years earlier by Walter Fuller. Cedric was then the film critic of one of the Express newspapers, and when Lord Beaverbrook ordered him to Hollywood, Cedric proposed that I should go with him.

We sailed from Southampton in the old Majestic. Among other celebrities on board we met Otto Harbach, author of The Desert Song and other famous musical plays, and Max Dreyfus, the doyen of American music publishers. There was much talk of the theatre and New York and I was as excited as any latter-day Pilgrim Father by my first glimpse of that fabulous sky-line with the towers of the down-town skyscrapers rising out of the mists of an early morning in Spring. I found New York, as I still find it, immensely stimulating.

Cedric had business to do for his newspaper so that I was left with plenty of time in which to explore Manhattan on my own. Those were still the days of the Gangster and the Speak-easy. On my first afternoon in Times Square I watched two stalwart thugs shoot their way out of a jewellery store, and paid my first visit to a speak-easy. The "speak" (to which I had been recommended by a shipboard acquaintance) was a furtive establishment in a basement below a fruit-shop. When I knocked tremulously at the green door, a small grid slid open and an appropriately sinister voice asked me what I wanted. After mentioning the name of my sponsor, I was admitted to a low dingily-lit bar-room crowded with drinkers of both sexes....

Cedric and I eventually left for California by air. I had never flown before, and the first sight of the machine did little to reassure me; metal aeroplanes were only just coming into fashion and ours was a contraption of canvas that seemed to me quite inadequate for the long flight. It required a lengthy pull at my hip-flask to get me aboard.

The flight then took two days, with an overnight "stop off" at Kansas City. On the second day we flew into a snow-storm over Texas and were forced down in the desert. After a long, cold interval we were picked up by motor-cars and driven to spend the night in the town of Amarillo.

In Hollywood Cedric and I settled into a small apartment at the Roosevelt Hotel. As representative of a leading London newspaper he had the entree to all the studios, then very active in the first flush of the talking picture. He was kind enough to take me with him on his rounds and I found myself, as wide-eyed as any juvenile movie-fan, face to face with the gods and goddesses of the screen. I met most of them and remember few of them - except for Sylvia Sidney with her quick wit and almost Oriental beauty and Douglas Fairbanks Junior, who remains my friend to this day.

(7) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

An old friend of Cedric Belfrage's was Upton Sinclair, the novelist at that time still active in the Socialist cause. Sinclair lived then in a wooden house in Pasadena so entangled in jasmine that, when we called to visit him, the perfume was almost stifling. A frail, yet dynamic man in the mid-fifties he talked fascinatingly for hours, communicating at intervals with his wife, who was upstairs in bed with a chill, by means of a police-dog to whose collar he tied notes. When we were about to leave, he said: "Well, I guess you boys would like a drink"; we accepted and were immediately regaled with two glasses of water! I took away with me an autographed copy of his latest novel The Flivver King which was an expose of the Henry Ford Empire.

(8) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

My little house was cool and comfortable, the big play-room ideal for parties. And parties seemed to be the order of the day; apparently no one could bear to stay at home in the evening, doing anything so restfully mundane as sewing or reading a book. I had discovered many old friends from London. There was Greer Garson, newly arrived and just as bored with Metro as myself; George Sanders, already a star, though three years ago he had entertained me to a half-pint with his last shilling; Reggie Gardiner, who had made a big name with his imitations of wallpaper; beautiful Margot Graham with a heart as large as the Hollywood Bowl; Andre Charlot, Charles Bennett, Guy Middleton, Bill Lipscombe, Phyllis Clare... so many English exiles that one felt that the Ivy and the Savoy Grill must have been quite deserted!

In Beverley Hills nobody walked; the pavements were always empty and, if occasionally I were to stroll home late at night from somebody's house, a prowl-car would draw up alongside me and a puzzled cop ask if anything was wrong. It became imperative for me to learn to drive the car, especially as the studios, if I was ever to visit them, were situated eight miles away. I had never been an enthusiast for the internal combustion engine; motor cars make me nervous, although I am content to ride as passenger with drivers who know all about them and their nasty little ways. With my good Korean as instructor, I cruised around the side-streets, obediently stopping, starting and changing gear...

That I had not been happy in Hollywood was not Hollywood's fault. It had given me six months of luxurious living in an Elysian climate, and the friendship of dear people whom I have never forgotten. And if I were invited to work there again today I would go west with gladness, for with age comes philosophy. In 1937 I had been a small cog in a titanic spendthrift machine, a minnow among the whales (and a few sharks) in the aquarium of the New Writers' Block. I had, I fondly think, no personal vanity, I only wanted to be allowed to work. The waste of money upon my unused services irked the peasant element in my make-up. And yet, when I say that I was "unhappy" in Hollywood, I am perhaps not using quite the right word: I was happy, as I usually have been in any circumstances, but felt at the same time thwarted and out of place.

(9) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

The first night of Paprika, when it came, was a disastrous failure. It was at the time of Munich; from outside the theatre the brass band of a Peace Procession vied audibly with the orchestra within; political fanatics invaded the dressing-rooms flourishing pamphlets, thereby so frightening the child actors in the cast that they burst into tears and had to be pushed, still weeping, onto the stage.

Towards the end of the piece an unknown actress, afterwards famous as Carol Lynne, sang a simple Victorian ballad and for the first time the audience broke into loud applause. In the wings that wise old trouper Helen Have took me by the arm. "Hear that, young man?" she said. "If that's all they can find to go mad about, you've got a flop! " And she was right. On the second night of Paprika there were more people (78) on the stage, than in the auditorium (53); after thirteen unhappy performances the play closed.

(10) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

After the German break-through into France the activities of "D-Section" on the Continent were severely curtailed and so I was sent away with others, to undergo a course of training in Explosives and Demolition. This was a severe test for somebody who had never cared particularly for "bangs"!

The course was held at a secret establishment in Hertfordshire. When we arrived there I observed with some misgivings that the Chief Instructor had had part of his jaw blown away, while his Sergeant Major was short of three fingers on one hand! For several days we were initiated into the mysteries of a new explosive known as plastic; it looked like sticks of children's plasticine and had the reputation of being both devastating and slightly undependable. With grave rnisgivir.gs we learned how to "crimp" a length of fuse to a detonator with our teeth, being warned at the same time that if we were to bite the "live" end of the latter we would as like as not blow our heads off !

As a final exercise each of us had to creep in the dead of night through a copse in which had been laid a length of railway-track. Our job after locating the track was to demolish it. After tamping a hefty charge under the rail, I inserted my Bickford fuse into the open end of the detonator, bit cautiously, expecting the damned thing to go off in my face, then touched off the fuse with a fusee-match, and ran for dear life. As I crashed into a tree and broke my spectacles, there was a deafening explosion and a considerable chunk of iron whizzed past my ear. The drinks we had in the mess that night to celebrate our graduation were very much appreciated by at least one member of the party!

(11) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

With the turn of the year I was transferred, with a number of other British officers, to the Psychological Warfare Branch of S.H.A.E.F. Our offices were in Inveresk House off the Strand, whither many years before I had been used to deliver the weekly column that I contributed to the Bystander. We were an "integrated" unit, under an American one-star General, whose principal aides were Richard Crossman, now a Socialist M.P., and William Paley, today the millionaire President of the Columbia Broadcasting System. The section to which I was attached specialised in Leaflet Warfare. The young officer who was our liaison with the Flying Fortress squadron which was to drop our paper ammunition upon the enemy, had invented a leaflet bomb a cardboard container which could be disintegrated at any distance from the ground by means of a time-fuse.

Nobody connected with the invasion, even in as remote a degree as myself, can ever forget the dramatic tension of the Spring. One April evening I stood in the garden of Philip Jordan's thatched cottage in Sussex watching the fanning searchlights and blaze of anti-aircraft fire that told of an enemy raid upon one of the seaside towns. Beside me in the dusk was a very pretty woman with auburn hair and kind brown eyes. Her name was Phyllis Gordon and for ten years past she had been an important part of my life, advising me, helping me, often, I am sure, weeping over my foolishness. That same morning Hermione and I had for the first time discussed the question of divorce, and so I was in a position to ask Phyllis if she would marry me when I became free. My proposal was accepted, and Philip, who heartily approved of the match, insisted upon opening his last bottle of Clicquot in celebration. Enchanting Phyllis, you took upon yourself that evening a responsibility that I am afraid was not to bring you unalloyed happiness !

In London we had already drafted our leaflets to be dropped over France on D-Day, appeals to the population, warnings to the German Army. These had been set up in type by a special secret department but could not for reasons of security be printed before D-1. The eventual postponement of the operation owing to bad weather meant that a number of elderly men had to be kept locked up in our printing works for 24 hours. Some of them, notably those whose wives had supper waiting for them on the hob, were very angry indeed!

My own job, once the Normandy landing had taken place, was to act as Intelligence liaison officer between headquarters in France and our squadron of Flying Fortresses in Hertfordshire. Early each morning, via a "scrambled" telephone conversation with the other side of the channel I learned the location of enemy units likely to respond to leaflet treatment.

Our library of leaflets, increasing every day, contained many with specialised appeal, angled, for example, towards Russian and Polish soldiers in certain of the enemy formations. A small masterpiece of its kind was the leaflet that contributed largely towards the surrender of Cherbourg. For general purposes we dropped twice a week a miniature German newspaper Nachtrichen fur die Truppe,

brilliantly devised and edited by a famous newspaper correspondent who was at the same time managing a bogus "Germany Army Radio Station" situated outside London. The interrogation of prisoners revealed that a large proportion of the enemy's troops believed that both the newspaper and the radio programme emanated from their own side of the line!

(12) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

The revue for which Val Parnell had commissioned my services was entitled Starlight Roof. In a night club setting under a starry sky, Vic Oliver conducted a small symphony orchestra, in the intervals of playing in sketches and acting as master of ceremonies. With him as stars he had that merry man-mountain Fred Emney, pretty Patricia Kirkwood and two American ballerinas, Marion Hightower and Barbara Perry. The composer of the music was George Melachrino who some years earlier had been my R.S.M. at the War Office.

Writing songs with George was an unusual experience. Being no sort of pianist, he would play the melodies to me on either a saxophone or a violin. With one of our songs, So Little Time, Pat Kirkwood used to bring down the house. As collaborator in the dialogue I had Matt Brooks, a comedy-writer from Broadway with an encyclopaedic knowledge of his business. Matt's most hilarious sketch for Starlight Roof concerned the misfortunes of Vic Oliver, newly wed to a famous striptease dancer (Barbara Perry), who found out on his honeymoon night that his bride could only remove her clothes to music! Not a very refined idea perhaps, but I never heard an audience laugh longer or more loudly. Everybody enjoyed it except Barbara; she was a girl of nice principles and used to blush visibly as she stripped!

An "unknown" in the cast of our show was the phenomenal child soprano, Julie Andrews. Dressed in a gym frock and school hat, she came out of the audience and, accompanied on the piano by Vic Oliver, sang an operatic aria in a coloratura that would not have disgraced Lily Pons. At the public dress rehearsal Julie's uncanny performance brought the house down. This had Bob Nesbitt really worried; he called it a "circus act", thought it out of keeping with his elegant revue.

(13) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

At the dress rehearsal of Love from Judy our composer, Hugh Martin, had introduced me to an American playwright by the name of Hy Kraft. It so happened that at the time Bernard Grun and I had in mind a musical play with an American background; it was to be based upon an episode in the life of Anton Dvorak, the Czech composer who after some years of teaching and conducting in the United States found in Illinois the inspiration for his famous symphony From the New World. This play (which we eventually entitled Summer Song) seemed to call for an American collaborator; we therefore enlisted Hy Kraft to help us with the story.

For the musical score of Summer Song we selected melodies from the music of Dvorak, including of course the New World symphony. There are people who maintain that this "borrowing" from the classics, as was done for Lilac Time (Schubert), Song of Norway (Grieg), and Kismet (Borodin) is both inartistic and distasteful, ethers who hold that, if done with delicacy, it may bring great melodies to listeners who might otherwise never have come to love them. Certainly Bernard's treatment of Dvorak cannot have been without taste, for the BBC, always sticklers in this respect, immediately passed the score of Summer Song for general broadcasting.

I have never enjoyed lyric writing so much; setting verses to such music was a happy change from writing "in syncopation". Not that it was a light task; certain of the Czech folk-dance rhythms were difficult to match with words. I have never found lyric-writing easy; as Oscar Hammerstein has put it: "A term like 'inspiration' annoys a professional author because it implies in its common conception that ideas and words are born in his brain as gifts from heaven and without effort".

The completion of Summer Song took myself and my partners two years in the course of which we produced seven different versions of the script and I wrote lyrics for eight more songs that were eventually used. During this long period I worked at nothing else, except for two versions of old plays for my good friends and customers "the amateurs".

Is is not to say that I was idle. I had been recently elected to the Council of the Performing Rights Society, the remarkable organisation which collects performing fees for authors and composers from all over the world. This was a great honour in my profession and one which I took with appropriate seriousness. I had also become Chairman of the Songwriters Guild of Great Britain, a professional body founded in 1947 by Ivor Novello, Sir Alan Herbert, Eric Coates, Haydn Wood, Richard Addinsell and others for the encouragement and protection of British popular music.

Since the war our lighter composers have increasingly needed the sort of help that the Songwriters' Guild can give. The market has been flooded with music from America exploited and publicised by means of technicolor films, stage plays, and gramophone records made by fashionable stars. Each year 15,000 songs are published in the USA, of which fewer than 1,000 ever achieve the "Hit Parade" and still fewer have any more than a passing vogue. The songs which are imported into Britain from America arrive with the status of proven "hits"; against these the British song, starting, so to speak, from scratch, has to battle for a hearing from the British listener. The odds are formidable indeed; the best that the Guild can do is to encourage help from the BBC and the recording companies and to see to it that no unfair pressure is brought to bear by vested interests from across the Atlantic.

(14) Eric Maschwitz, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957)

A man aged 55, height 6 feet 2 inches, weight 173 lbs, hair still plentiful but inclined increasingly to grey, eyes brown and now rather short-sighted, teeth woefully incomplete, his only "distinguishing mark" (as the passports have it) a mole the size of a sixpence upon his left thigh. A man who has lately lived too much indoors, smoked far too many cigarettes, drunk perhaps a little too much whisky, yet who still has a voracious appetite, particularly for bread, reacts suitably to the contiguity of an attractive woman, can sleep his eight hours, without stirring the bed-clothes, like an an exhausted child. The circulation of his blood is not, alas, as nimble as it used to be so that recently, to his distress, he has suffered for the first time from a chilblain! He still loves to play cricket, is a fair hand at snooker and not entirely useless with a 12-bore gun. He has a sneaking love of luxury, but is at the same time comparatively impervious to discomfort.

What of his intellectual capacity? This is no blazing intellect; its owner thinks too quickly and words come to him too easily for that. He has read enormously and learned too little from books; felt too much and thought too little; his reactions are quick and too often superficial. He cannot fathom the game of chess. Has no technical understanding of Music, never scored more than 12 per cent of marks in a paper on Mathematics. And yet he is not without a certain practical sense, has spent a dozen years of his life as a business executive responsible for the control of a large staff and the spending of a great deal of other people's money.