Isaiah Berlin

Isaiah Berlin, the only child of Mendel Borisovitch Berlin and Marie Volshonok Berlin, was born in Riga, Latvia, on 6th June 1909. It was a difficult birth and the doctor placed forceps on his left arm and yanked him into the world so violently that the ligaments were permanently damaged. His father was a prosperous timber merchant whose main business was supplying wooden sleepers for the Russian railways.

During the First World War the family moved to Saint Petersburg. He did not attend school and was educated at home. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks nationalised the railways and his father was employed as a state contractor. His biographer, Alan Ryan, has pointed out: "There Berlin saw the brutality of revolution at first hand. He was horrified by the spectacle of a mob hounding a policeman in the street, and dragging him off to his presumed death. In later years he maintained that his hatred of political violence had its origins in that experience, though it was very far from making him a pacifist. Antisemitism was never far below the surface of the Soviet revolution, and it was a constant threat during the subsequent civil war. Nevertheless the Berlins fared no worse and no better than most other middle-class Russians who found their homes requisitioned and their lives threatened by the ubiquitous informers who hoped to advance themselves by denouncing their neighbours."

In 1919 the Cheka ransacked their home. Mendel Berlin now made the decision to leave the capital: "The feeling of being imprisoned, no contact with the outside world, the spying all round, the sudden arrests and the feeling of absolute helplessness against the whim of any hooligan parading as a Bolshevik". The family moved back to Latvia, now an independent republic. At the Latvian-Soviet border, the Jews were taken off the train and were sent to a Russian bath for delousing. Isaiah later recalled: "We were Jews... we were not Russian... we were something else."

Mendel Berlin established himself in the timber trade but it was decided to emigrate to Britain. In February 1921 the family arrived in London. They rented a home in Surbiton and Isaiah attended the Arundel House School. As Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "The loneliness of a child exiled into a foreign tongue is easy to imagine. English schoolboy lore - football teams, cartoon characters, dirty songs and jokes, snobberies and cruelties - was beyond his ken, while all the impressive things he knew seemed worthless or an embarrassment."

Isaiah Berlin was occasionally called a "dirty Jew" but he was impressed by the way the other boys protected him from these outbreaks of prejudices. He was never to forget these acts of kindness that he insisted this was "deeply and uniquely English". He later wrote "that decent respect for others and the toleration of dissent is better than pride and a sense of national mission; that liberty may be incompatible with, and better than, too much efficiency; that pluralism and untidiness are, to those who value freedom, better than the rigorous imposition of all-embracing systems, no matter how rational and disinterested, better than the rule of majorities against which there is no appeal."

Mendel Berlin was successful in the timber trade and in 1922 the family moved into a three-storey terraced house in Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park. However, Isaiah later recalled that his mother was not happy: "She resented being married to him. Felt he was dull, depended on her. She wanted to be loved, she wanted to be lifted, nothing ever happened, so all her love was turned on me." Marie Berlin was more interested in politics than her husband and was chairwoman of the Brondesbury Zionist Society.

Isaiah Berlin attended St Paul's School. In 1927 he sat the examination for Corpus Christi College and won an entrance scholarship in classics. At university he made friends with Stephen Spender, Bernard Spencer, Goronwy Rees, Victor Rothschild, W.H. Auden, Arthur Calder-Marshall, John Langshaw Austin, Stuart Hampshire, Sheila Lynd and Shiela Grant Duff. Another friend, Diana Hubback, said that he "seemed completely adult at a time when his youthful friends were only just emerging from adolescence." In 1930 inherited the editorship of Oxford Outlook , an undergraduate magazine, from Calder-Marshall.

Berlin was impressed by his philosophy tutor, Frank Hardie, who taught him how to think clearly: "Obscurity and pretentiousness and sentences which doubled over themselves he wrung right out of me, from then until this moment." Michael Ignatieff has argued: "Hardy became the single most important intellectual influence upon Berlin's undergraduate life: orienting him towards the British empiricism that became his intellectual morality. It was remarkable that someone so undisciplined and intuitive should have realised how much he needed what the mild, retiring Scotsman had to teach him. But this was to prove a lifetime pattern: seeing in others what he lacked himself, and having the shrewdness and self-confidence to go in search of it."

In 1931 Berlin developed a close friendship with Maurice Bowra, the Dean of Wadham College. During this period Bowra liked to portray himself as the "leader of the immoral front front, all those communists, homosexuals and non-conformists who stood for pleasure, conviction and sincerity against the dull, fastidious mandarins of the Oxford senior common rooms." Berlin later recalled "the words came in short sharp bursts of precisely aimed, concentrated fire as image, pun, metaphor, parody, seemed spontaneously to generate one another in a succession of marvellously imaginative patterns, sometimes rising to high, wildly comical fantasy."

Berlin gained a first-class degree in Greats and the John Locke Prize in philosophy. He considered going into journalism but was not offered a job after being interviewed by C.P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian. As a result he returned to the University of Oxford to read Philosophy, Politics and Economics. During this period he became friends with some interesting figures such as Virginia Woolf, Victor Rothschild, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, W.H. Auden, Douglas Jay, Peggy Garnett and David Astor.

A. J. Ayer described meeting Berlin in his autobiography, Part of My Life (1977): "It was through the Jowett Society that I came to know Isaiah, or as his friends then called him, Shaya Berlin. We already had a slight connection in that his father, who came from Riga, was also in the timber trade and knew both my father and my father's partner Mr Bick, but although we had known of each other through the Bicks, we had never met. Isaiah had gone to school at St Paul's and had come up to Oxford a year ahead of me as a classical scholar at Corpus. Andrew and I called on him in the belief that a meeting of the Jowett Society was being held in his rooms, but either we had been misinformed, or the venue of the meeting had been changed, and we found him alone.... On this occasion, we had hardly begun talking before I said to Andrew, "Let's not go to the meeting. This man is much more interesting." Not caring to be treated as if he had been put on show, Isaiah hustled us away to the meeting, but this was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted for over forty years."

Ayer added: "One of the things that first brought us together was our common interest in philosophy. This is an interest that we no longer share, since Isaiah was persuaded by the American logician H. M. Sheffer, in the early nineteen-forties, that the subject had developed to a point where it required a mastery of mathematical logic which was not within his grasp: thereafter he chose to cultivate the lusher field of political theory. His approach to philosophy had indeed always been more eclectic than mine and more critical than constructive. In our frequent discussions, his part was usually to find unanswerable objections to the extravagant theories that I advanced. He once described me to a common friend as having a mind like a diamond, and I think it is true that within its narrower range my intellect is the more incisive. On the other hand, he has always had the readier wit, the more fertile imagination and the greater breadth of learning. The difference in the working of our minds is matched by a difference in temperament, which has sometimes put a strain upon our friendship. I am more resilient, more reckless and more intolerant; he is more mature, more expansive and more responsible. At times he has found me too theatrical and been shocked by my sensual self-indulgence. I have sometimes wished that he were more revolutionary in spirit. I credit us both with a strong moral sense, but it expresses itself in rather different ways."

In October 1932 Berlin was given a post as tutor in philosophy in New College. He later recalled: "I knew I wasn't first rate, but I was good enough. I was quite respected. I wasn't despised." One of his students was Richard Crossman. The two men did not get on. Berlin later argued that: "Crossman was a left-wing Nazi. He was anti-capitalist, hated the civil service, respectability, conventional values, of a decent honest dreary kind. What he wanted was young men singing songs, students linking arms, torchlit parades. There was a strong fascist streak in him. He wanted power, hated liberalism, mildness, kindness, amiability."

Berlin's first book, Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, was published in 1939. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has argued: "Berlin never mastered Marx's economic theory in Das Kapital. Yet he took pride in getting inside the head of an antipathetic figure, and in a larger sense, the sojourn with Marx had a profound influence on his later thought. It gave him a lifelong target, for he genuinely loathed Marxian ideas of historical determinism and was to argue that they served as the chief ideological excuse for Stalin's crimes. At the same time, he was influenced by the Marxian sense that ideas and values were historical, and that the values of social groups in class struggle were incompatible." Alan Ryan has pointed out: "The book was both a publishing success and a double landmark in Berlin's life. In the first place, it was one of the first works in English that treated Marx absolutely objectively - neither belittling the real intellectual power of his work, nor descending into hagiography. Second, it revealed Berlin's unusual talent as a historian of ideas - or more exactly as a biographer of ideas. Berlin was no admirer of Marx, and wholly deplored the political consequences of his ideas, but he entered into the intellectual world of Marx and his fellow revolutionaries as few biographers have known how to do."

Berlin had broken off contact with Guy Burgess when he had joined Britannia Youth, a neo-fascist group that sent British schoolboys to Nazi Party rallies in Germany. However, in June 1940, Burgess arrived in Berlin's rooms at New College to apologize for his behaviour: "I'm terribly unstable, it just came over me. Everything in England was so dreary. I thought at least the Nazis knew where they were going. Anyway I don't expect you to forgive me." Burgess then revealed that Harold Nicolson had recruited him to undertake a mission to the Soviet Union on behalf of MI5.

Berlin agreed to the proposal but when they got to Quebec Burgess was recalled to London. Berlin now went to New York City where he visited his friends, Felix Frankfurter and Reinhold Niebuhr. He also contacted Richard Stafford Cripps and volunteered his services to the war effort. Cripps recommended he returned to England to receive further orders. After a meeting in the Ministry of Information, Berlin received instructions to join the British Security Coordination (BSC).

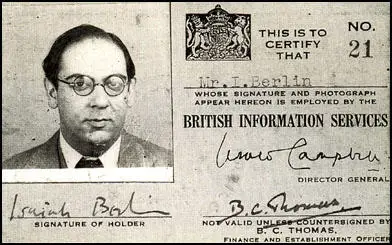

Berlin arrived in New York City in January 1941. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "Isaiah Berlin's job was to get America into the war. He was to be a propagandist, working with trade unions, black organizations and Jewish groups. He lived in mid-town Manhattan hotels and went to work every morning at the British Information Services on the forty-fourth floor of a building in the Rockefeller Center. There he went through piles of American press clippings ranged in shoe-boxes. From these he put together a weekly report for the Ministry of Information on the state of American public opinion. In the early months of 1941 the isolations were in the ascendant and the prospects of getting America into the war seemed remote."

Daphne Straight, who worked in the same office as Berlin described him as a "voluble, slightly mad professor - pockets overflowing with sweets, handkerchiefs, press cuttings, lapels dusted with cigarette ash". He visited editors and tried to persuade them to publish articles that provided a positive image of Britain. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Berlin also worked closely with supporters of American intervention in the Second World War. This included Rabbi Stephen Wise and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandelis. Other contacts included Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky, the leaders of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA).

Berlin was also instructed to work on Arthur Hays Sulzberger who was being criticised by the British government for not supporting the cause as well as the New York Herald Tribune. One of Berlin's colleagues, Valentine Williams had a meeting with Sulzberger and on 15th September, 1941. That night he reported to Hugh Dalton, Minister of Economic Warfare: "I had an hour with Arthur Sulzberger, proprietor of the New York Times, last week. He told me that for the first time in his life he regretted being a Jew because, with the tide of anti-semitism rising, he was unable to champion the anti-Hitler policy of the administration as vigorously and as universally as he would like as his sponsorship would be attributed to Jewish influence by isolationists and thus lose something of its force." He also suggested to Berlin, who lobbied Sulzberger to be more outspoken about the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany: "Mr Berlin, don't you believe that if the word Jew was banned from the public press for fifty years, it would have a strongly positive influence."

Berlin also had regular meetings with journalists such as Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Philip Graham, Joseph Alsop, Arthur Krock and Marquis Childs, in an effort to publish information favourable to the British. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Despite his efforts, by the end of 1941, 80% of the American public was still opposed to the sending of American troops to Europe.

In 1942 Berlin was transferred from New York City to Washington, and for the remainder of the war drafted reports on behalf of Lord Halifax, who had succeeded Lord Lothian as British ambassador. Berlin had a good relationship with Halifax although he was "not of this century" and was like "a creature from another planet". These reports were read by Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden. His biographer, Alan Ryan has commented that "Berlin walked with some skill the fine line between exact reporting and colouring the news to enhance the prospects of a desired policy. It was a skill he especially needed to preserve relations with Chaim Weizmann and other Zionist friends. He was happy to do what he could to keep doors in both the American and British governments open for his friends, but he was also acutely aware of Foreign Office doubts about Zionist aspirations. He took care neither to betray his friends nor to destroy his own usefulness by becoming an object of suspicion to his employers, although in 1943 he was instrumental in obstructing a joint British-American declaration against the establishment of a post-war Jewish state." During this period he spent a lot of time at the home of Chip Bohlen on Dunbarton Avenue. George Kennan was also a regular visitor and one observer described the three men as "a homogeneous, congenial trio."

In February 1944, an article appeared in New York Post by Edgar Ansel Mowrer, that claimed that the Allies were "passively permitting the extermination of the European Jews when they could be saving a large number of them". Berlin was involved in drafting a reply to these charges: "The British and American governments are doing everything in their power, by warnings to Hitler and by negotiations with the neutrals, to put a stop to this massacre and to assist in the escape of its victims. For obvious reasons the full extent of their activity cannot be made public."

On 8th September 1945, Berlin, taken advantage of the fact that the Soviet Union was now an ally of Britain, flew to Moscow in order to visit relatives he had not seen since leaving the country 25 years earlier. He was told by his cousins that anti-Semitism, in abeyance during the war, was now making a return. Berlin also had meetings with Sergi Eisenstein, who had been dismissed from the Kamerny Theatre by Joseph Stalin.

Berlin had a meeting with the novelist, Boris Pasternak. He told him the story how Stalin phoned him in 1934 and asked him about the poem that Osip Mandelstam had read at a small private gathering in Moscow. Pasternak claimed that he was unable to remember if the poem was an attack on Stalin. Unconvinced by his answer, Stalin interjected, "If I were Mandelstam's friend I should have known better how to defend him." Mandelstam was sent to a labour camp and died in December 1938.

Berlin also arranged to visit Mikhail Zoshchenko, the successful author of Tales (1923), Esteemed Citizens (1926), What the Nightingale Sang (1927) and Nervous People (1927). Zoshchenko satires were popular with the Russian people and he was one of the country's most widely read writers in the 1920s. Although Zoshchenko never directly attacked the Soviet system, he was not afraid to highlight the problems of bureaucracy, corruption, poor housing and food shortages. In the 1930s Zoshchenko came under increasing pressure to conform to the idea of socialist realism.

During the Second World War Mikhail Zoshchenko was expelled to Tashkent with the poet, Anna Akhmatova. However, his exile had made him very ill and Berlin, who described him as "yellow of complexion, withdrawn, incoherent, pale, weak and emaciated", shook his hand but did not have the heart to engage him in conversation. However, he did spend a long time with Akhmatova and it was the beginning of a long-term friendship.

Berlin returned to his post as tutor in philosophy in New College. The author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) points out that he had an unusual style of teaching: "He was an eccentric teacher, often taking tutorials in pyjamas and dressing-gown, or actually in bed... He didn't bore his students, but they often bored him." In 1946 he wrote that his students were "dull and polite and spiritless with too much army life in them, scores and scores of them cluttering up every available chink of time and space, morning and afternoon and evening."

Berlin moved to the right in the 1940s and fell out with several friends who still remained on the left. He was invited to the United States to give lectures on the Cold War. In one lecture, Democracy, Communism and the Individual , Berlin argued that the terms "liberty, equality and fraternity" were "beautiful but incompatible". Despite this the New York Times published an article falsely claiming that he was urging American universities to take up Marxist studies. This resulted in the FBI making inquiries about his political past.

In 1949 Berlin gave a talk on BBC radio where he argued that Britain must recognise that its ultimate interests lay neither with the British Empire nor with Europe but with the United States. The speech was attacked by those on the right like Lord Beaverbrook, who wrote in the Evening Standard about his defeatism about the empire and his subservience towards the Americans. He was also criticised by those on the left like Harold Laski and G.D.H. Cole, who disliked his commitment to American capitalism. Berlin, who had always voted for the Labour Party, changed to the Liberal Party in the 1950 General Election. He considered supporting Winston Churchill but "he was too coarse, too brutal, and I didn't want him back in."

Although he was a fervent anti-communist, Berlin disapproved of McCarthyism. He wrote to a friend: "I am indeed anti-communist, but perhaps when heretics are being burnt right and left it is not the bravest thing in the world to declare one's loyalty to the burners, particularly when one disapproves of the Inquisition." When his friend, Robert Oppenheimer, was denied a security clearance because of his alleged communist sympathies, Berlin joined others in writing letters of protest.

When his friend, Guy Burgess, fled to the Soviet Union in June 1951, Berlin was a willing informer on his left wing associates. Peter Wright of MI5 wrote that "Isaiah Berlin and Arthur Marshall, were wonderfully helpful, and met me regularly to discuss their contemporaries at Oxford and Cambridge... Berlin had a keen eye for Burgess' social circle, particularly those whose views appeared to have changed over the years. He also gave me sound advice on how to proceed with my inquiries." Berlin also told Wright to investigate Anthony Blunt: "Anthony's trouble is that he wants to hunt with society's hounds and run with the Communist hares!" However, another friend from university, Goronwy Rees, gave an interview to The People newspaper suggesting that Berlin might have been working for Burgess in the 1930s.

Berlin wrote several articles about the danger of communism for Foreign Affairs, that obtained praise from Henry Luce. He also wrote for Encounter Magazine that was covertly funded by the CIA. He later recalled: "I was (and am) pro-American and anti-Soviet, and if the source had been declared I would not have minded in the least... What I and others like me minded very much was that a periodical which claimed to be independent, over and over again, turned out to be in the pay of American secret Intelligence."

His biographer, Alan Ryan, has argued: "Berlin enjoyed the company of women, but thought himself sexually unattractive, and believed until his late thirties that he was destined to remain a bachelor. All Souls was a luxurious bachelor society, and Berlin's affection for his mother was sufficient to suggest that he would neither be driven into marriage by the discomforts of single life nor lured into it by the need for stronger emotional attachments than the unmarried life provided. It was therefore somewhat to the surprise of his numerous friends that on 7th February 1956 he married Aline Elisabeth Yvonne Halban, the daughter of the banker Baron Pierre de Gunzbourg, of Paris. He thereby acquired three stepsons as well as a beautiful and well-connected wife whose accomplishments had included the women's golf championship of her native France. They established themselves in Aline's substantial and elegant house on the outskirts of Oxford (Headington House, nicknamed Government House by Berlin's more left-wing friends), and there they lived and entertained - or, as the same friends had it, held court - for the next forty years. Although he had embarked on marriage rather late, Berlin never ceased to recommend the married condition, and his happiness was a persuasive advertisement for what he preached."

On 31st October 1958, Berlin gave a lecture at the University of Oxford entitled Two Concepts of Liberty : "Everything is what it is: liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience. If the liberty of myself or my class or nation depends on the misery of a number of other human beings, the system which promotes this is unjust and immoral. But if I curtail or lose my freedom, in order to lessen the shame of such inequality, and do not thereby materially increase the individual liberty of others, an absolute loss of liberty occurs. This may be compensated for by a gain in justice or in happiness or peace, but the loss remains, and it is a confusion of values to say that although my 'liberal' individual freedom may go by the board, some other kind of freedom - social or economic - is increased."

Conservatives such as Leo Strauss and Alan Bloom welcomed Berlin's critique of the totalitarian temptation. However, he was attacked by the Canadian philosopher, Charles Taylor who argued that self-realisation did not necessarily lead to totalitarian tyranny and that individuals could use their freedom to transform themselves through knowledge and self-understanding. Taylor added that Berlin's defence of liberty was little more than a mere apologia for free-market capitalism.

Berlin had seen an early draft of Dr. Zhivago. He told Boris Pasternak that he should not publish the book, with the words that "martyrdom was a moral temptation like any other and should be resisted". Pasternak disagreed and the book was published in Italy in 1958. The Soviet regime was furious and began the harassment that Berlin believed contributed to his early death in 1960.

Berlin upset his left-wing friends by refusing to join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In May 1961, when President John F. Kennedy administration sponsored the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, Berlin refused to sign a statement condemning the operation. He argued that Fidel Castro "may not be a Communist but I think he cares as little for civil liberties as Lenin or Trotsky." Perry Anderson of the New Left Review attacked him as being one of the "European immigrants to Britain who had done most to serve up to the English a self-congratulatory picture of their own supposedly liberal virtues."

In 1961 E. H. Carr, made an attack on Berlin's idea that historians should be chiefly concerned not with explanation but with moral evaluation. Surely, Carr argued, no one seriously supposed that a historian's task was to bother with the question of whether Oliver Cromwell or Adolf Hitler were "bad fellows". Their task was rather to understand the factors that he enabled them to come to power and the forces which their rule unleashed. Berlin replied that Marxist theory put an almost exclusive emphasis on abstract socio-economic causation and neglected the importance of the ideas, beliefs and intentions of individuals.

Berlin was invited to attend a small private dinner in honour of Charles Bohlen in October 1962. Other people invited included President John F. Kennedy, Philip Graham, Joseph Alsop and Arthur Schlesinger. During the dinner Kennedy asked Berlin about what the Soviets do when "backed into a corner". Berlin later recalled: "I've never known a man who listened to every single word that one uttered more attentively. His eyes protruded slightly, he leant forward towards one, and one was made to feel nervous and responsible by the fact that every word registered."

After the Cuban Missile Crisis Kennedy told Berlin that the incident would never expunge the stain of Cuba No. 1 (Bay of Pigs). He asked Berlin to conduct a seminar on communism. This took place on 12th December, 1962. The seminar was attended by McGeorge Bundy, Robert McNamara, Arthur Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and Walt Rostow. Berlin attempted to explain how communism imported into Europe as a "secular, theoretical, abstract doctrine" was transformed by its contact with the earnest Russian intelligentsia into Leninism, as a "fiery, sectarian, quasi-religious faith".

In 1963, the Marxist academic, Isaac Deutscher, was being considered for a professorship in political studies at Sussex University. Berlin, who served on the university's academic advisory board, was asked by the Vice-Chancellor for his opinion on Deutscher. His comment, that Deutscher was "the only man whose presence in the same academic community as myself I should find morally intolerable" meant that he was not offered the post. Berlin was embarrassed when this letter was published in Black Dwarf in 1969 and he was denounced as an anti-communist witch-hunter.

In 1966 Berlin became president of Wolfson College. Under the name Iffley College, this had been a new and under-financed graduate college. It was renamed Wolfson College in acknowledgement of the generosity of Sir Isaac Wolfson's Foundation, which paid the cost of the new building. It also received funding from the Ford Foundation. He held the post for the next nine years.

In 1967 Berlin was asked to contribute to Authors Take Sides on Vietnam, a collection of statements about the Vietnam War. Berlin upset both right and left when he argued that the Americans should not have intervened but, having sent in troops, they should not withdraw precipitously, lest the South Vietnamese be massacred by communist forces. He also suggested that he supported the idea of the domino theory and that if South Vietnam was lost the other pro-Western regimes in the region would also fall.

Berlin argued: "Happy are those who live under a discipline which they accept without question, who freely obey the orders of leaders, spiritual or temporal, whose word is fully accepted as unbreakable law; or those who have, by their own methods, arrived at clear and unshakeable convictions about what to do and what to be that brook no possible doubt. I can only say that those who rest on such comfortable beds of dogma are victims of forms of self-induced myopia, blinkers that may make for contentment, but not for understanding of what it is to be human."

At the age of seventy Berlin relinquished all his public positions except his seat on the Covent Garden Board and his place as a trustee of the National Gallery. With the help of Henry Hardy, Berlin published a series of books made up of old and new articles. This included Vico and Herder: Two Studies in the History of Ideas (1976), Russian Thinkers (1978), Concepts and Categories: Philosophical Essays (1978), Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (1979), Personal Impressions (1980), The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas (1990), The Sense of Reality: Studies in Ideas and their History (1996) and The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays (1997).

Isaiah Berlin died at the Acland Nursing Home, 25 Banbury Road, Oxford, on 5 November 1997.

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Ignatieff, A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998)

The loneliness of a child exiled into a foreign tongue is easy to imagine. English schoolboy lore - football teams, cartoon characters, dirty songs and jokes, snobberies and cruelties - was beyond his ken, while all the impressive things he knew seemed worthless or an embarrassment.

(2) A. J. Ayer, Part of My Life (1977)

It was through the Jowett Society that I came to know Isaiah, or as his friends then called him, Shaya Berlin. We already had a slight connection in that his father, who came from Riga, was also in the timber trade and knew both my father and my father's partner Mr Bick, but although we had known of each other through the Bicks, we had never met. Isaiah had gone to school at St Paul's and had come up to Oxford a year ahead of me as a classical scholar at Corpus. Andrew and I called on him in the belief that a meeting of the Jowett Society was being held in his rooms, but either we had been misinformed, or the venue of the meeting had been changed, and we found him alone. Having introduced ourselves, we entered into conversation. It can be said of Isaiah as Dr Johnson said of Burke that he is "such a man, that if you met him for the first time in the street where you were stopped by a drove of oxen, and you and he stepped aside to take shelter but for five minutes, he'd talk to you in such a manner that when you parted you would say, this is an extraordinary man." On this occasion, we had hardly begun talking before I said to Andrew, "Let's not go to the meeting. This man is much more interesting." Not caring to be treated as if he had been put on show, Isaiah hustled us away to the meeting, but this was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted for over forty years.

One of the things that first brought us together was our common interest in philosophy. This is an interest that we no longer share, since Isaiah was persuaded by the American logician H. M. Sheffer, in the early nineteen-forties, that the subject had developed to a point where it required a mastery of mathematical logic which was not within his grasp: thereafter he chose to cultivate the lusher field of political theory. His approach to philosophy had indeed always been more eclectic than mine and more critical than constructive. In our frequent discussions, his part was usually to find unanswerable objections to the extravagant theories that I advanced. He once described me to a common friend as having a mind like a diamond, and I think it is true that within its narrower range my intellect is the more incisive. On the other hand, he has always had the readier wit, the more fertile imagination and the greater breadth of learning. The difference in the working of our minds is matched by a difference in temperament, which has sometimes put a strain upon our friendship. I am more resilient, more reckless and more intolerant; he is more mature, more expansive and more responsible. At times he has found me too theatrical and been shocked by my sensual self-indulgence. I have sometimes wished that he were more revolutionary in spirit. I credit us both with a strong moral sense, but it expresses itself in rather different ways.

(3) Isaiah Berlin, lecture at the University of Oxford (31st October 1958)

Everything is what it is: liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience. If the liberty of myself or my class or nation depends on the misery of a number of other human beings, the system which promotes this is unjust and immoral. But if I curtail or lose my freedom, in order to lessen the shame of such inequality, and do not thereby materially increase the individual liberty of others, an absolute loss of liberty occurs. This may be compensated for by a gain in justice or in happiness or peace, but the loss remains, and it is a confusion of values to say that although my 'liberal' individual freedom may go by the board, some other kind of freedom - social or economic - is increased.

(4) Michael Ignatieff, A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998)

Berlin was probably the first Westerner to hear the story of the ominous telephone conversation of 1934 between Pasternak and Stalin about the poet Osip Mandelstam, then under suspicion for having recited a savage poem attacking 'the Kremlin Mountaineer' at a small private gathering in Moscow. Pasternak at first thought the call was a practical joke and hung up. Stalin then called again, and Pasternak, realising that he was talking directly to the Leader, said, in his most ecstatic mode, that he had always known this would happen and hoped they would meet immediately and talk about ultimate matters of life and death, and the future of Russia. Stalin brushed all this aside and asked roughly whether Pasternak had been present when Mandelstam had read the poem. Pasternak equivocated; Stalin pressed him. Was Mandelstam a great poet, a master? Pasternak replied that this was not the issue - meaning that poets should be treated decently whatever the quality of their work. At which point Stalin famously interjected, "If I were Mendelstam's friend I should have known better how to defend him.".

(5) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

Isaiah Berlin and Arthur Marshall, were wonderfully helpful, and met me regularly to discuss their contemporaries at Oxford and Cambridge... Berlin had a keen eye for Burgess' social circle, particularly those whose views appeared to have changed over the years. He also gave me sound advice on how to proceed with my inquiries.

(6) Isaiah Berlin, The Pursuit of the Ideal (1988)

Happy are those who live under a discipline which they accept without question, who freely obey the orders of leaders, spiritual or temporal, whose word is fully accepted as unbreakable law; or those who have, by their own methods, arrived at clear and unshakeable convictions about what to do and what to be that brook no possible doubt. I can only say that those who rest on such comfortable beds of dogma are victims of forms of self-induced myopia, blinkers that may make for contentment, but not for understanding of what it is to be human.

(7) Michael Ignatieff, A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998)

As they talked together in Pasternak's Moscow flat, the poet revealed some of his torment at having collaborated with the regime, and his anguish at being Jewish. The two were deeply connected. He longed to be considered an authentic Russian patriot and to have his work accepted as the true voice of the Russian people: yet, as a Jew, he was never allowed to feel authentically Russian. Lacking this sense of authenticity, he had accommodated himself and deformed his talent in order to survive. This twin shame was a source of genuine self-torture. Isaiah had noticed how insistent Pasternak had been to point out that Peredelkino had once been part of the estate of the Russian patriot and Slavophile, Yuri Samarin. Pasternak wanted to identify, not with the liberal (and sometimes Jewish) intelligentsia, but with the more authentically Russian Slavophiles. `This passionate, almost obsessive desire to be thought a Russian writer' led him to be sharply negative about his Jewish origins. He gave the impression, Isaiah tartly observed, of wishing that he had been born a flaxen-haired, blue-eyed peasant's son. Pasternak insisted that Jews should assimilate and said that he considered himself a believing, if idiosyncratic, Christian. The whole subject, Isaiah noticed, caused him `visible distress'." Ten years later, when Isaiah returned to Peredelkino, Pasternak handed him a manuscript and said he would publish in the West whatever the consequences. Berlin went away, read the chapters and immediately knew that Pasternak's crisis of identity had been resolved. He had put all his equivocations behind him in a single act of defiance and genius: the writing of Dr Zhivago.

(8) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

The most insistent propaganda in those days declared that humanitarianism and liberalism and democratic forces were played out, and that the choice now lay between two bleak extremes, Communism and Fascism - the red or the black. To those who were not carried away by this patter the only light that was left in the darkness was the administration of Roosevelt and the New Deal in the United States. At a time of weakness and mounting despair in the democratic world Roosevelt radiated confidence and strength. He was the leader of the democratic world, and upon him alone, of all the statesmen of the 1930s, no cloud rested - neither on him nor on the New Deal, which to European eyes still looks a bright chapter in the history of mankind. It is true that his great social experiment was conducted with an isolationist disregard of the outside world, but then it was psychologically intelligible that America, which had come into being in the reaction against the follies and evils of a Europe perpetually distraught by religious or national struggles, should try to seek salvation undisturbed by the currents of European life, particularly at a moment when Europe seemed about to collapse into a totalitarian nightmare. Roosevelt was therefore forgiven, by those who found the European situation tragic, for pursuing no particular foreign policy, indeed for trying to do, if not without any foreign policy at all, at any rate with a minimum of relationship with the outside world, which was indeed to some degree part of the American political tradition.

His internal policy was plainly animated by a humanitarian purpose. After the unbridled individualism of the 1920s, which had led to economic collapse and widespread misery, he was seeking to establish new rules of social justice. He was trying to do this without forcing his country into some doctrinaire strait-jacket, whether of socialism or State capitalism, or the kind of new social organisation which the Fascist regimes flaunted as the New Order.Social discontent was high in the United States, faith in businessmen as saviours of society had evaporated overnight after the famous Wall Street Crash, and Roosevelt was providing a vast safety-valve for pent-up bitterness and indignation, and trying to prevent revolution and construct a regime which should provide for greater economic equality and social justice - ideals which were the best part of the tradition of American life - without altering the basis of freedom and democracy in his country...

But Roosevelt's greatest service to mankind (after ensuring the victory against the enemies of freedom) consists in the fact that he showed that it is possible to be politically effective and yet benevolent and human: that the fierce left- and right-wing propaganda of the 1930s, according to which the conquest and retention of political power is not compatible with human qualities, but necessarily demands from those who pursue it seriously the sacrifice of their lives upon the altar of some ruthless ideology, or the practice of despotism - this propaganda, which filled the art and talk of the day, was simply untrue. Roosevelt's example strengthened democracy everywhere, that is to say the view that the promotion of social Justice and individual liberty does not necessarily mean the end of all efficient government; that power and order are not identical with a strait-jacket of doctrine, whether economic or political; that it is possible to reconcile individual liberty - a loose texture of society - with the indispensable minimum of organising and authority.

(9) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

Oxford in the 1920s and early 1930s was stiffer, more class-conscious, hierarchical and self-centred than it is now (it may, of course, be only because I was young that I think so - but there is, I believe, a good deal of objective evidence for this too), and Felix Frankfurter had an uncommon capacity for melting reserve, breaking through inhibitions, and generally emancipating those with whom he came into contact. Only the genuinely self-important and pompous resented this, and they did so most deeply...

He talked copiously, with an overflowing gaiety and spontaneity which conveyed the impression of great natural sweetness; his manner contrasted almost too sharply with the reserve, solemnity and, in places, vanity and self-importance of some of the highly placed persons who seated themselves round him and engaged his attention. He spoke easily, made his points sharply, stuck to all his guns, large and small, and showed no tendency to retreat from views and political verdicts some of which were plainly too radical for the more conservative of the public personages present; they were hailed with the greatest approval by the majority of our generation of fellows - then very young - who formed the outer circle of Frankfurter's audience, and were divided from most of their elders by irreconcilable differences of view on most of the political and social issues of that day - Manchuria, the Bankers' Ramp, Fascism, Hitler, unemployment, slumps, collective security.

(10) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

When I met Aldous Huxley in 1935 or 1936, in the house of a mutual friend, Lord Rothschild, in Cambridge, I expected to be overawed and perhaps sharply snubbed. But he was very courteous and very kind to everyone present. The company played intellectual games, so it seemed to me, after nearly every meal; it took pleasure in displaying its wit and knowledge; Huxley plainly adored such exercises, but remained uncompetitive, benevolent and remote. When the games were over at last, he talked, without altering his low, monotonous tone, about persons and ideas, describing them as if viewed from a great distance, as queer but interesting specimens, odd, but no odder than many others in the world on which he seemed to look as a kind of museum or encyclopaedia. He spoke with serenity and disarming sincerity, very simply. There was no malice and very little conscious irony in his conversation, only the mildest and gentlest mockery of the most innocent kind. He enjoyed describing prophets and mystagogucs, but even such figures as Count Kevserling, Ouspensky and Gurdjieff, whom he did not much like, were given their due and indeed more than their due; even Middleton Murry was treated more mercifully and seriously than in the portrait in Point Counter Point. Huxley talked very well: he needed an attentive audience and silence, but he was not self-absorbed or domineering, and presently everyone in the room would fall under his peaceful spell; brightness and glitter Went out of the air, everyone became calm, serious, interested and contented. The picture I have attempted to draw may convey the notion that Huxley, for all his noble qualities, may (like some very good men and gifted writers) have been something of a bore or a preacher. But this was not so at all, on the only occasions on which I met him. He had great moral charm and integrity, and it was these rare qualities (as with the otherwise very dissimilar G. E. Moore), and not brilliance or originality, that compensated and more than compensated for any lack-lustre quality, and for a certain thinness in the even, steady flow of words to which we all listened so willingly and respectfully.

The social world about which Huxley wrote was all but destroyed by the Second World War, and the centre of his interests appeared to shift from the external world to the inner life of men. His approach to all this remained scrupulously empirical, directly related to the facts of the experience of individuals of which there is record in speech or in writing....

(11) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

The political consequences of the devastation of war and civil war, of the famine, the systematic destruction of lives and institutions by the dictatorship, ended the conditions in which poets and artists could create freely. After a relatively relaxed period during the years of the New Economic Policy, Marxist orthodoxy grew strong enough to challenge and, in the late 1920s' crush all this unorganised revolutionary activity. A Collectivist proletarian art was called for; the critic Averbakh led a faction of Marxist zealots against what was described as unbridled individualistic literary licence - or as formalism, decadent aestheticism, kowtowing to the West, opposition to socialist collectivism.

Persecution and purges began; but since it was not always possible to predict which side would win, this alone, for a time, gave a certain grim excitement to literary life. In the end, in the early 1930s, Stalin decided to put an end to all these politico-literacy squabbles, which he plainly regarded as a sheer waste of time and energy. The leftist zealots were liquidated; no more was heard of proletarian culture or collective creation and criticism, nor yet of the non-conformist opposition to it. In 1934 the Party (through the newly created Union of Writers) was put in direct charge of literary activity. A dead level of State-controlled orthodoxy followed: no more argument; no more disturbance of men's minds; the goals were economic, technological, educational - to catch up With the material achievements of the enemy - the capitalist world - and overtake it. If the dark mass of illiterate peasants and workers was to be welded into a militarily and technically invincible modern society, there was no time to be lost; the new revolutionary order was surrounded by a hostile world bent on its destruction.

(12) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

It was a warm, sunlit afternoon in early autumn. Pasternak, his wife and his son Leonid were seated round a rough wooden table in the tiny garden at the back of the dacha. The poet greeted us warmly. He was once described by his friend the poetess Marina Tsvetaeva as looking like an Arab and his horse: he had a dark, melancholy, expressive, very race face, now familiar from many photographs and his father's paintings; he spoke slowly, in a low tenor monotone, with a continuous, even sound, something between a humming and a drone, which those who met him almost always remarked; each vowel was elongated as if in some plaintive, lyrical aria in an opera by Tchaikovsky, but with more concentrated force and tension...

He spoke in magnificent, slow-moving periods, with occasional intense rushes of words; his talk often overflowed the banks of grammatical structure - lucid passages were succeeded by wild but always marvelously vivid and concrete images - and these might be followed by dark words when it was difficult to follow him - and then he would suddenly come into the clear again; his speech was at all times that of a poet, as were his writings. Someone once said that there are poets who are poets when they write poetry and prose-writers when they write prose; others are poets in everything that they write. Pasternak was a poet of genius in all that he did and was; his ordinary conversation displayed it as his writings do...

Here, in recounting the episode to me, Pasternak again embarked oil one of his great metaphysical flights about cosmic turning-points in the world's history, which he wished to discuss with Stalin - it was of supreme importance that he should do so - I can easily imagine that he spoke in this vein to Stalin too. At any rate, Stalin asked him again whether he was or was not present when Mandel'shtam read the lampoon. Pasternak answered again that what mattered most was his indispensable meeting with Stalin, that it must happen Soon, that everything depended on it, that they must speak about ultimate issues, about life and death. "If I were Mandel'shtam's friend I should have known better how to defend him," said Stalin, and put down the receiver. Pasternak tried to ring back but, not surprisingly, failed to get through to the leader. The episode evidently preyed deeply upon him: he repeated to me the version I have just recounted on at least two later occasions, and told the story to other visitors, although, apparently, in somewhat different forms. His efforts to rescue Mandel'shtam, in particular his appeal to Bukharin, probably helped to preserve him at least for a time - Mandel'shtam was finally destroyed some years later - but Pasternak clearly felt, perhaps without good reason, but as anyone not blinded by self-satisfaction or stupidity might feel, that perhaps another response might have done more for the condemned poet.

He followed this story with accounts of other victims: Pil'nyak, who anxiously waited ("was constantly looking out of the window") for an emissary to ask him to sign a denunciation of one of the men accused of treason in 1936, and because none came, realised that he too was doomed. He spoke of the circumstances of Tsvetaeva's suicide in 1941, which he thought might have been prevented if the literary bureaucrats had not behaved with such appalling heartlessness to her. He told the story of a man who asked him to sign an open letter condemning Marshal Tukhachevsky; when Pasternak refused and explained the reasons for his refusal, the man burst into tears, said that the poet was the noblest and most saintly human being that he had ever met, embraced him fervently, and then went straight to the secret police and denounced him.

(13) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

Pasternak was acutely sensitive to the charge of accommodating himself to the demands of the Party or the State - he seemed afraid that his mere survival might be attributed to some unworthy effort to placate the authorities, some squalid compromise of his integrity to escape persecution. He kept returning to this point, and went to absurd lengths to deny that he was capable of conduct of which no one who knew him could begin to conceive him to be guilty. One day he asked me whether I had read his wartime volume of poems On Early Trains; had I heard anyone speak of it as a gesture of conformity with the prevailing orthodoxy? I said truthfully that I had never heard this, that it seemed to me a ludicrous suggestion.

Anna Akhmatova, who was bound to him by the deepest friendship and admiration, told me that when she was returning to Leningrad from Tashkent, where in 1941 she had been evacuated from Leningrad, she stopped in Moscow and visited Pcredelkino. Within a few hours of arriving she received a message from Pasternak that he could not see her - he had a fever - he was in bed - it was impossible. On the next day the message was repeated. Oil the third day he appeared before her looking unusually well, with no trace of any ailment. The first thing he did was to ask her whether she had read his latest book of poems: he put the question with so painful an expression on his face that she tactfully said that she had not read them yet; at which his face cleared, he looked vastly relieved and they talked happily. He evidently felt needlessly ashamed of these poems, which, in fact, were not well received by the official critics. It evidently seemed to him a kind of half-hearted effort to write civic poetry - there was nothing he disliked more intensely than this genre.

(14) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

Anna Andrecvna Akhmatova was immensely dignified, with unhurried gestures, a noble head, beautiful, somewhat severe features, and an expression of immense sadness. I bowed - it seemed appropriate, for she looked and moved like a tragic queen - thanked her for receiving me, and said that people in the West would be glad to know that she was in good health, for nothing had been heard of her for many years. "Oh, but an article on me has appeared in the Dublin Review," she said, "and a thesis is being written about my work, I am told, in Bologna." She had a friend with her, an academic lady of some sort, and there was polite conversation for some minutes. Then Akhmatova asked me about the ordeal of London during the bombing: I answered as best I could, feeling acutely shy and constricted by her distant, somewhat regal manner.

(15) Isaiah Berlin, Personal Impressions (1980)

When we met in Oxford in 1965, Akhmatova described the details of the attack upon her by the authorities. She told me that Stalin was personally enraged by the fact that she, an apolitical, little-published writer, who owed her security largely to having contrived to live comparatively unnoticed during the early years of the Revolution, before the cultural battles which often ended in prison camps or execution, had committed the sin of seeing a foreigner without formal authorisation, and not just a foreigner, but an employee of a capitalist government. "So our nun now receives visits from foreign spies," he remarked (so it is alleged), and followed this with obscenities which she could not at first bring herself to repeat to me. The fact that I had never worked in any intelligence organisation was irrelevant: all members of foreign embassies or missions were spies to Stalin. "Of course," she went on, "the old man was by then out of his mind. People who were there during this furious outbreak against me, one of whom told me of it, had no doubt that they were speaking to a man in the grip of pathological, unbridled persecution mania." On the day after I left Leningrad, on 6 January 1946, uniformed men had been placed outside the entrance to her staircase, and a microphone was screwed into the ceiling of her room, plainly not for intelligence purposes but to frighten her. She knew that she was doomed - and although official disgrace followed only some months later, after the formal anathema pronounced over her and Zoshchenko by Zhdanov, she attributed her misfortunes to Stalin's personal paranoia. When she told me this in Oxford, she added that in her view we - that is, she and I - inadvertently, by the mere fact of our meeting, had started the Cold War and thereby changed the history of mankind. She meant this quite literally; and, as Amanda Haight testifies in her book, was totally convinced of it, and saw herself and me as world-historical personages chosen by destiny to begin a cosmic conflict (this is indeed directly reflected in one of her poems). I could not protest that she had perhaps, even if the reality of Stalin's violent fit of anger and of its possible consequences were allowed for, somewhat overestimated the effect of our meeting on the destinies of the world, since she would have felt this as an insult...

She knew, she said, that she had not long to live: the doctors had made it plain that her heart was weak, and therefore she was patiently waiting for the end; she detested the thought that she might be pitied; she had faced horrors and knew the most terrible depths of grief, and had exacted from her friends the promise that they would not allow the faintest gleam of pity to show itself, to suppress it instantly if it did; some had given way to this feeling, and with them she had been obliged to part; hatred, insults, contempt, misunderstanding, persecution, she could bear, but not sympathy if it was mingled with compassion - would I give her my word of honour? I did, and have kept it. Her pride and dignity were very great.