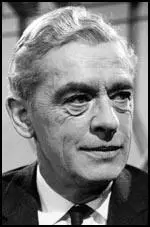

Goronwy Rees

Goronwy Rees, the younger son and youngest of four children of the Revd Richard Jenkyn Rees (1868–1963) and his wife, Apphia Mary James was born in Aberystwyth on 29th November, 1909. According to Kenneth O. Morgan: "The family was Welsh-speaking and its tone sombre. In 1921, when Rees was only eleven, his father was unexpectedly caught up in a massive political controversy, when he clashed with his chapel congregation following his support of a Lloyd George Liberal in opposition to an Asquithian in the Cardiganshire by-election. The family had to leave Aberystwyth in 1923 and moved to Roath in Cardiff."

Rees was educated at Cardiff High School for Boys (1923–8) and then gained a scholarship to New College. One of his friends at university was A. J. Ayer. In his autobiography, Part of My Life (1977) Ayer commented: "Goronwy Rees, to whom Martin Cooper introduced me. As Martin reported it to me, Goronwy's first reaction was one of surprise that Martin should make friends with anyone so ugly, but either my looks improved or he became reconciled to them, since he has remained the closest to me of any of the Oxford friends of my youth. He himself had the romantic good looks that one associates with Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, and was full of vitality and charm. He had been brought up at Aberystwyth, where his father, a distinguished theologian, was much in demand as a preacher, and though he had a great affection and respect for his father, he was in moral and intellectual revolt against his Calvinist principles. He had been to school in Cardiff, where he had been conspicuous as an athlete as well as a scholar and had played in a trial as scrum-half for the Welsh schoolboys."

Kenneth O. Morgan has argued: "Goronwy Rees was a strikingly handsome, charming, intellectually gifted man. He had a graceful literary style and a remarkable command of languages. In Oxford in the thirties he was an attractive figure - amusing, unconventional, with a beguiling air of being the Celtic outsider, and yet later the charm could seem a professional artifice...He won many admirers, male and female, but made as many enemies."

Rees took first-class honours in philosophy, politics, and economics in 1931 and was then elected to a prize fellowship at All Souls, the first Welshman so nominated. In that year he published his first novel, The Summer Flood, based on life in South Wales. A. J. Ayer later commented: "He (Rees) had literary ambitions and his first novel, a love-story with some philosophical overtones, was written while he was still an undergraduate. His critical standards were high and I remember that when I published my affected and ill-written essay about bull-fighting, he advised me quite sharply to stick to philosophy."

Rees then spent time in Berlin before becoming a leader writer on the Manchester Guardian (1932–5) and then assistant editor of The Spectator. His second novel, A Bridge to Divide, appeared in 1937. During this period he had relationships with Shiela Grant Duff, Elizabeth Bowen and Rosamond Lehmann. In 1934 he became friends with Guy Burgess. The two men were both Marxist and in 1937 Burgess confessed to Rees that he was a Soviet agent. Rees became disillusioned with communism after the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Rees took an officer's course at Sandhurst Military Academy was commissioned in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. On 20th December 1940 he married Margaret Ewing (1921–1976). They were to have five children, two girls and three boys. Rees took part in the raid on Dieppe and later was on the staff of General Bernard Montgomery. He was also colonel in the Allied Control Commission in Germany at the end of the war.

Rees continued to write novels and in 1950 he published his most successful novel, Where No Wounds Were. In 1951 Guy Burgess defected to the Soviet Union with Donald Maclean. Suspicions fell on Rees and he was interviewed by Dick White. Rees admitted that Burgess had told him he was a Soviet spy in 1937. However, he insisted that he had refused to be recruited by Burgess. Ress also claimed that Guy Liddell and Anthony Blunt were Soviet spies. White suspected that Rees had been spying for the Soviets but was unable to persuade him to confess.

Peter Wright, who worked for MI5, claimed in his book, Spycatcher (1987): "Rees... told White, then the head of Counterespionage.... that he knew Burgess to have been a longtime Soviet agent. Burgess, he claimed, had tried to recruit him before the war, but Rees, disillusioned after the Molotov-von Rippentrop pact, refused to continue any clandestine relationship. Rees also claimed that Blunt, Guy Liddell, a former MI6 officer named Robert Zaehner, and Stuart Hampshire, a brilliant RSS officer, were all fellow accomplices. But whereas Blunt was undoubtedly a Soviet spy, the accusations against the other three individuals were later proved groundless... Dick White disliked Rees intensely, and thought he was making malicious accusations in order to court attention."

Kenneth O. Morgan has pointed out: "He (Rees) returned to All Souls in 1951 and served successfully as the bursar of its considerable estates. Then in 1953, at the invitation of its president, Thomas Jones, Rees returned unexpectedly to Aberystwyth to become principal of the University College of Wales. This proved to be a catastrophe. Rees made a strong impression initially and a memorable principal's inaugural lecture recalled Mark Pattison in insisting that universities should mould character and culture... However, his unconventional social behaviour offended local sensibilities, while his English wife was never happy in so small and Welsh a town." Revelations about his relationship with Guy Burgess forced him to resign from this post in 1957.

In January 1964, MI5 officer, Arthur Martin, interviewed Michael Straight, a suspected spy. He confessed and claimed that he had been recruited by Anthony Blunt. Martin, now armed with Straight's story, went to see Blunt. This time he made a confession. He admitted being a Soviet agent and named John Cairncross, Peter Ashby, Brian Symon and Leo Long as spies he had recruited.

As Rees had named Blunt in 1951, he was now re-interviewed.Peter Wright later revealed that Rees insisted that Guy Liddell, Deputy-Director-General of MI5 had been a Soviet spy. Wright argued: "The accusation against Guy Liddell was palpably absurd. Everyone who knew him, or of him, inside MI5 was convinced that Liddell was completely loyal." On further investigation, Wright also dismissed the claims made by Rees about Robert Zaehner and Stuart Hampshire.

Rees, who had developed strong anti-communist views, wrote a monthly column for Encounter. He also wrote two highly praised volumes of autobiography, A Bundle of Sensations (1960) and A Chapter of Accidents (1972). Later, both volumes were published together as Sketches in Autobiography. Other books by Rees included The Multi-Millionaires: Six Studies in Wealth (1961), The Rhine (1967), St Michael, a History of Marks and Spencer (1969) and The Great Slump: Capitalism in Crisis (1970). Rees also appeared in the BBC television series The Brains Trust.

Goronwy Rees died of cancer in Charing Cross Hospital in London, on 12 December 1979. It has been claimed that Rees, gave a deathbed confession that he had indeed been a Soviet spy. He also admitted that Guy Liddell was also a traitor and had been part of the Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and Anthony Blunt spy ring.

In 1999 KGB defector Vasili Mitrokhin claimed that Rees had been a Soviet agent. According to Sally Davies: "His daughter Jenny Rees said he was just passing on tittle tattle because he was part of the Oxbridge set and knew the famous five who were unmasked... She said he was a minor player and not actually a spy because she always maintained that if he were a spy they would have a KGB file on him, well there now appears that there was."

Primary Sources

(1) Goronwy Rees met Anthony Blunt on 28th May, 1951. Rees disagreed with Blunt when he used E. M. Forster's view that betraying one's friend was worse than betraying one's country. He wrote about this meeting in his autobiography A Chapter of Accidents (1972)

He (Anthony Blunt) was greatly distressed and said he would like to see me. On Monday May 28th he came to my house in the country, and on an almost ideally beautiful English summer day we sat by the river and I gave him my reasons for thinking that Guy had gone to the Soviet Union: his violent anti-Americanism, his certainty that America would involve us all in a Third World War, most of all the fact that he had been and perhaps still was a Soviet agent. He pointed out, very convincingly as it seemed to me, that these were really not very good reasons for denouncing Guy to MI;. His anti-Americanism was an attitude which was shared by many liberal-minded people and if this alone were sufficient reason to drive him to the Soviet Union, Moscow at that moment would be besieged by defectors seeking asylum. On the other hand, my belief that he might be a Soviet agent rested simply on one single remark made by him years ago and apparently never repeated to anyone else; in any case Guy's public professions of anti-Americanism were hardly what one would expect from a professional Soviet agent. Most of all he pointed out that Guy was after all one of my, as of his, oldest friends and to make the kind of allegations I apparently proposed to make about him was not, to say the least of it, the act of a friend. He was the Cambridge liberal conscience at its very best, reasonable, sensible, and firm in the faith that personal relations are the highest of all human values.

I said Forster's antithesis was a false one. One's country was not some abstract conception which it might be relatively easy to sacrifice for the sake of an individual; it was itself made up of a dense network of individual and social relationships in which loyalty to one particular person formed only a single strand. In that case, he said, I was being rather irrational because after all Guy had told me he was a spy a very long time ago and I had not thought it necessary to tell anyone. I said that perhaps I was a very irrational person; but until then I had not really been convinced that Guy had been telling the truth.

(2) BBC Wales (16th September, 1999)

The Welsh author and academic Goronwy Rees has been named as a spy by the KGB defector Vasili Mitrokhin. Until now there had been nothing more than suspicion that Rees was a Soviet agent.

BBC Wales's Sally Davies: "No evidence that he passed anything of note" But he has been unmasked in the KGB archives smuggled out of Moscow by Mitrokhin, which also revealed Melita Norwood and John Symonds were spies.

Sally Davies, who has been looking into the claims, said the Mitrokhin Archives revealed that Rees had two code names - Fleet and Gross. He was regarded as a key element in Guy Burgess's recruitment strategy at Oxford University in the late 1930s.

"His daughter Jenny Rees said he was just passing on tittle tattle because he was part of the Oxbridge set and knew the famous five who were unmasked," she said.

"She said he was a minor player and not actually a spy because she always maintained that if he were a spy they would have a KGB file on him, well there now appears that there was."

The KGB regarded Rees as a useful contact because of his position as a fellow of All Souls Oxford where he would come into contact with top politicians.

But most commentaries suggest his communist sympathies were ideological rather than political.

He was recruited after writing an essay on mass unemployment in the South Wales Valleys.

But the archives confirm that Rees passed no information of any great importance to the Soviet regime - and that he ended his contact after three years because he was so sickened by the Nazi-Soviet pact.

However according to Mitrokhin, Guy Burgess wanted Rees assassinated because he was afraid of what he knew.