Nazi-Soviet Pact

In the 1930s Joseph Stalin became increasingly concerned that the Soviet Union would be invaded by Nazi Germany. Stalin believed the best way to of dealing with Germany was to form an anti-fascist alliance with countries in the west. Stalin argued that even Adolf Hitler would not start a war against a united Europe. Adam B. Ulam, the author of Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) has argued: "Soviet diplomacy sought (in a much more realistic way than that of Britain and France) to avoid war. To do Stalin justice, he never made a secret greater than his desire to avoid war, or more precisely to avoid Russia's military involvement in one." (1)

On 18th March, 1939, Maxim Litvinov, Commissar for Foreign Affairs, denounced Hitler's decision to occupy Prague. Later that day, the British Foreign Office, asked Litvinov what would be the Soviet Union's attitude be towards Hitler if he ordered the invasion of countries such as Poland and Rumania. On 17th April, Stalin replied when he proposed an alliance between Britain, France and the Soviet Union, where the three powers would jointly guarantee all the countries between the Baltic and the Black Sea against aggression. (2)

British Foreign Policy & the Soviet Union

Neville Chamberlain did not like the idea. He wrote to a friend: "I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears." (3)

After the successful invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hitler began to make demands on the Polish government. This included a request for the return of the free city of Danzig and the amendment of the Polish corridor. Not surprisingly, Poland called on the British government for help. On 24th April, 1939, Colonel Józef Beck, the Polish foreign minister, arrived in London and proposed a secret understanding involving Britain, France and Poland. Chamberlain welcomed the suggestion as he wanted to pursue a policy of deterrence, without extreme provocation." (4)

The guarantee to Poland, which France joined, was officially announced on 31st March, 1939. David Lloyd George, immediately objected to the agreement. As he pointed out: "If war occurred tomorrow, you could not send a single battalion to Poland." (5) Chamberlain responded that he believed the guarantee would point "not towards war, which wins nothing or settles nothing, cures nothing, ends nothing" but would open the way towards "a more wholesome era, when reason will take place of force." (6)

On 13th April, further Anglo-French guarantees were offered to Rumania, Greece and Turkey. The following week the government introduced conscription for all males aged twenty and twenty-one. It also announced that spending limits on the army, navy and air force were abandoned and a ministry of supply to co-ordinate the supply of war materials was established. Hitler and Mussolini responded by signing a military alliance - the Pact of Steel - which added further to the idea of an inevitable war. (7)

The chiefs of staff supported the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance. On 16th May, Ernle Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, Minister for Coordination of Defence, strongly urged the conclusion of an Anglo-Soviet agreement. He warned that if the Soviet Union stood aside in a European war it might "secure an advantage from the exhaustion of the western powers" and that if negotiations failed, a Nazi-Soviet agreement was a strong possibility. Chamberlain rejected the advice and said he preferred to "extend our guarantees" in eastern Europe rather than sign an Anglo-Soviet alliance. (8)

A debate on the subject took place in the House of Commons on 19th May, 1939. The debate was short and was "practically confined to the leaders of Parties and to prominent ex-Ministers". Chamberlain made it clear that he had severe doubts about Stalin's proposal. David Lloyd George, the former prime minister called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. Clement Attlee had been campaigning for a military alliance with the Soviet Union since September, 1938, during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. (9) Attlee argued in the House of Commons that the government should form a "firm union between Britain, France and the USSR as the nucleus of a World Alliance against aggression". The government was "dilatory and fumbling" and was in danger of letting Stalin slip out of their grasp and into Hitler's hands." (10)

Winston Churchill, made a passionate speech where he urged Chamberlain to accept Stalin's offer: "There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge." (11)

On 24th May, 1939, the Cabinet discussed whether to open negotiations for an Anglo-Soviet alliance. The Cabinet was overwhelmingly in favour of an agreement. This included Lord Halifax who feared that if Britain did not do so the Soviet Union would sign an alliance with Nazi Germany. Chamberlain conceded that "in present circumstances, it was impossible to stand out against the conclusion of an agreement" but he stressed the "question of presentation was of the utmost importance." He therefore insisted that attempts should be made to hide any agreement under the banner of the League of Nations. (12)

In June, 1939, a public opinion poll showed that 84 per cent of the British public favoured an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. Negotiations progressed very slowly and it has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998), that "Chamberlain did not seem to care less whether an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed at all, kept placing obstructions in the way of concluding an agreement swiftly." (13) Chamberlain admitted: "I am so sceptical of the value of Russian help that I should not feel that our position was greatly worsened if we had to do without them." (14)

Russian and German Cooperation (1939)

Stalin's own interpretation of Britain's rejection of his plan for an anti-fascist alliance, was that they were involved in a plot with Germany against the Soviet Union. This belief was reinforced when Chamberlain met with Adolf Hitler at Munich and gave into his demands for the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Stalin now believed that the main objective of British foreign policy was to encourage Germany to head east rather than west. Stalin now decided to develop a new foreign policy. Stalin realized that war with Germany was inevitable. However, to have any chance of victory he needed time to build up his armed forces. The only way he could obtain time was to do a deal with Hitler. Stalin was convinced that Hitler would not be foolish enough to fight a war on two fronts. If he could persuade Hitler to sign a peace treaty with the Soviet Union, Germany was likely to invade Western Europe instead. (15)

Nazi-Soviet Pact

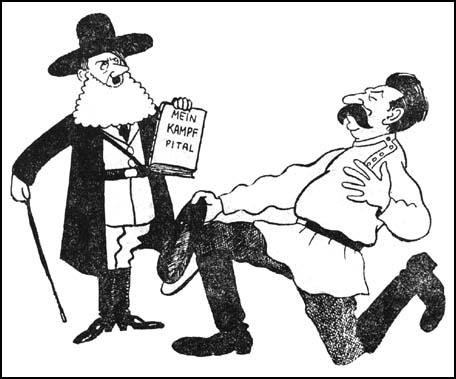

Stalin was frustrated by the British approach and dismissed Maxim Litvinov, his Jewish Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Litvinov had been closely associated with the Soviet Union's policy of an anti-fascist alliance. Time Magazine reported that there were several possible reasons for the replacement of Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov. "Most ominous - and least likely - explanation of the change: Comrade Stalin had decided to ally himself with Führer Hitler. Obviously Comrade Litvinov, born of Jewish parents in a Polish town (then Russian), could not be expected to complete such an alliance with rabidly Aryan Nazis. More likely: the Soviet Union was going to follow an isolationist policy (almost as bad for the British and French). By turning isolationist it would let Herr Hitler know that as long as he keeps away from Russia's vast stretches he need not fear the Red Army. Russia might even supply the Nazis with needed raw materials for conquests. Comrade Stalin still hankered after an alliance with Great Britain and France and by dismissing his experienced, alliance-seeking Foreign Commissar was simply trying to scare the British and French into signing up. But the most likely explanation was that in the bluff and counter-bluff of present European diplomacy, Dictator Stalin was simply clearing the decks to be ready at a moment's notice to jump either way." (16)

Walter Krivitsky, a former NKVD agent, who had fled to America in the early months of 1939 was asked by a journalist what he thought were the reasons for Stalin's sacking of Litvinov. He replied, "Stalin has been driven to the parting of roads in his foreign policy and had to choose between the Rome-Berlin axis and the Paris-London axis... Litvinov personified the policy which brought the Soviet government into the League of Nations which raised the slogan of collective security, which raised the slogan of collective security, which claimed to seek collaboration with democratic powers. That policy has collapsed." (17)

However, despite the fact that Krivitsky knew Stalin very well, his warnings were ignored. (18) Negotiations continued between Britain and the Soviet Union. The main stumbling-block concerned the rights of the Soviets to "rescue any Baltic state from Hitler, even if it did not want to be rescued". Britain insisted that they would only cooperate with Soviet Russia if Poland were attacked and agreed to accept Soviet assistance. This deadlock could not be broken and Molotov suggested that they concentrated on military talks. However, the British representatives in the talks were instructed to "go very slowly". The negotiations finally ended in failure on 21st August. (19)

Molotov now began secret negotiations with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. He later claimed: "To seek a settlement with Russia was my very own idea which I urged on Hitler because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict. After a short ceremonial welcome the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and myself.... Stalin spoke - briefly, precisely, without many words; but what he said was clear and unambiguous and showed that he, too, wished to reach a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin used the significant phrase that although we had 'poured buckets of filth' over each other for years there was no reason why we should not make up our quarrel." (20)

On 28th August, 1939, the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed in Moscow. It was reported: "Late Sunday night - not the usual time for such announcements - the Soviet Government revealed a pact, not with Great Britain, not with France, but with Germany. Germany would give the Soviet Union seven-year 5% credits amounting to 200,000,000 marks ($80.000,000) for German machinery and armaments, would buy from the Soviet Union 180,000.000 marks' worth ($72,000,000) of wheat, timber, iron ore, petroleum in the next two years". (21) Apparently, the day after the agreement was signed, Stalin told Lavrenti Beria: "Of course, it's all a game to see who can fool whom. I know what Hitler's up to. He thinks he's outsmarted me, but actually it's I who have tricked him." (22)

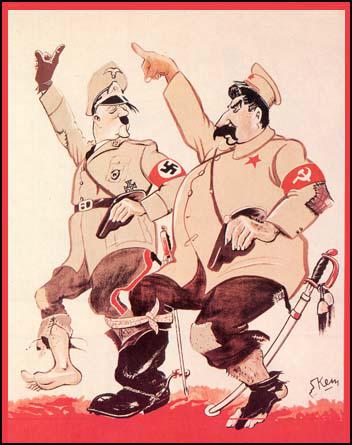

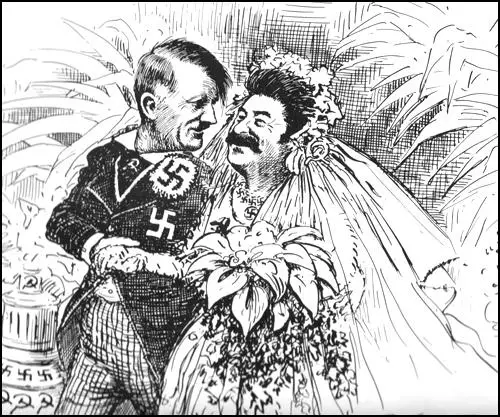

Under the terms of the agreement, both countries promised to remain neutral if either country became involved in a war. The cartoonist, David Low, who had long campaigned for an alliance with the Soviet Union, wrote: "Britain and France were dragged to war under such uninspiring and disadvantageous circumstances that it seemed hardly possible for them to win. What a situation! In gloomy wrath at missed opportunity and human stupidity I drew the bitterest cartoon of my life, Rendezvous, the meeting of the 'Enemy of the People' with the 'Scum of the Earth' in the smoking ruins of Poland." (23)

Walter Krivitsky, whose predictions had proved correct, argued in The New Leader: "Not only are the American people shocked, but far more the unhappy masses of Germany and Russia who have paid and will continue to pay for this triumph with their blood. Such master strokes are eloquent proof of the return by the totalitarian states to the darkest phases of secret diplomacy such as characterized the epoch of Absolutism... For the democratic world the importance of the pact lies in that it has finally ripped the mask from Stalin's face. I believe that in those countries where the free word still exists, the master stroke of diplomacy is the death stroke of Stalinism as an active force. I believe this because after nearly 20 years of service for the Soviet government, I am convinced that democracy; despite its present perilous position, is the sole path for progressive humanity." (24)

Nikita Khrushchev was involved in the negotiations with Joachim von Ribbentrop. He later explained why Stalin was willing to reach an agreement with Hitler. "I believe the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of 1939 was historically inevitable, given the circumstances of the time, and that in the final analysis it was profitable for the Soviet Union. It was like a gambit in chess: if we hadn't made that move, the war would have started earlier, much to our disadvantage. It was very hard for us - as Communists, as anti-fascists - to accept the idea of joining forces with Germany. It was difficult enough for us to accept the paradox ourselves." (25)

Decline in Party Membership

The signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact had a disastrous impact on members of communist parties throughout the world. John Gates, a senior figure in the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), wrote: "The announcement on August 23, 1939, that the Soviet Union and Germany had signed a non-aggression pact came like a thunderclap, not least of all to the communist movement. Leaders and rank-and-file members were thrown into utter confusion. The impossible had happened. We looked hopefully for an escape clause in the treaty, but the official text provided none... Statements now began to come from Moscow - both from the Soviet press and the Communist International - which made clear a big change in policy was under way. When the Nazis now invaded Poland and Britain and France declared war against Germany, the Soviet position was that British and French imperialists were responsible for the war, that this was an imperialist war and that neither side should be supported." (26)

Whittaker Chambers, was another senior figure in the CPUSA who was very upset by the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. He was also employed as a spy by the Soviet Union. He later pointed out: "Two days after Hitler and Stalin signed their pact - I went to Washington and reported to the authorities what I knew about the infiltration of the United States Government by Communists. For years, international Communism, of which the United States Communist Party is an integral part, had been in a state of undeclared war with this Republic. With the Hitler-Stalin pact that war reached a new stage. I regarded my action in going to the Government as a simple act of war, like the shooting of an armed enemy in combat." (27)

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was in a similar position. It had been demanding that Britain should join an alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. However, as Francis Beckett, the author of Enemy Within: The Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995) has pointed out, with the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, "Stalin had made it (CPGB) look and feel both foolish and dishonest". (28)

Outbreak of War

Lord Halifax argued that the Nazi-Soviet Pact did not make any difference as British policy had "always discounted Russia, so materially the position is not really changed." (29) On 22nd August, 1939, Chamberlain told the Cabinet, "It is unthinkable that we would not carry out our obligations to Poland." (30) Despite these comments he sent Hitler and unequivocal letter, approved by the Cabinet, which stated that Britain intended to stand by Poland. On 24th August, Chamberlain gained parliamentary agreement to pass the Emergency Powers Act. The following day, a formal Anglo-Polish military alliance was signed, to reinforce the British resolve not to abandon Poland. (31)

On 25th August, 1939, Hitler sent a letter to Chamberlain in which he demanded the Danzig and Polish corridor questions be settled immediately. In return for a settlement, Hitler offered a non-aggression pact to Britain and promised to guarantee the British Empire and to sign a treaty of disarmament. (32) Some appeasers such as Nevile Henderson, Richard Austen Butler and Horace Wilson, wanted to do a deal with Hitler. They were accused by Oliver Harvey of "working like beavers for a Polish Munich". (33)

The reply to Hitler went through several drafts, until it was finally agreed by the whole Cabinet on 28th August. In the letter, Chamberlain suggested direct Polish-German talks to settle the issue peacefully, but would not "acquiesce in a settlement which put in jeopardy the independence of the state to whom they had given their guarantee." (34) In response, Hitler demanded a Polish emissary "with full powers" go to Berlin on 30th August 1939, but the Polish government refused. (35)

On 31st August, 1939, Adolf Hitler gave the order to attack Poland. The following day fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility". (36)

At a meeting of the Cabinet on 2nd September, the Cabinet wanted the prime minister to declare war on Germany. Chamberlain refused and argued it was still possible to avoid conflict. That night he announced in the House of Commons that he was offering Hitler a conference to discuss the subject of Poland if the "Germans agreed to withdraw their forces (which was not the same as actually withdrawing them), the British government would forget everything that had happened, and diplomacy could start again." (37)

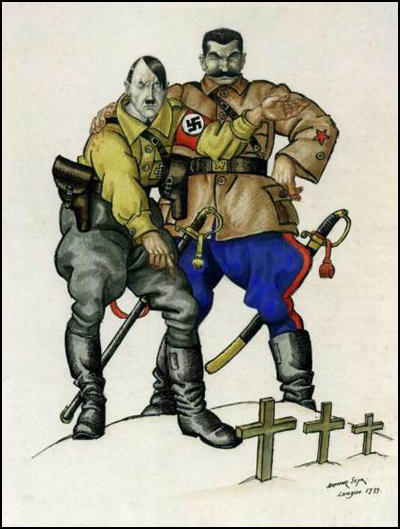

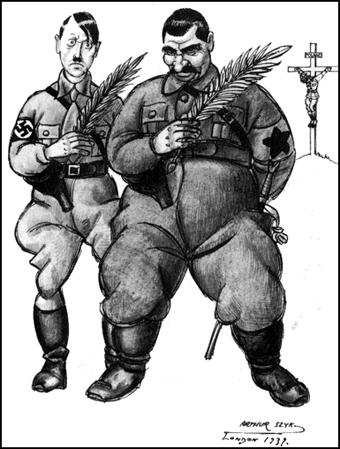

On hearing the news of the invasion, the Polish cartoonist, Arthur Szyk, now living in the United States, produced a series of cartoons including Peace Be With You. It has been claimed by Joseph Darracott, the author of A Cartoon War (1989), has pointed out: "Arthur Szyk's bitter comment on the Russo-German Pact is an admirable example of his meticulous draughtsmanship... Hitler and Stalin are shown holding palms of peace: behind them a soldier hangs on a cross inscribed Poland." (38)

At a meeting of the Central Committee of the CPGB on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." William Gallacher disagreed: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades."

Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the CPGB, made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten.... I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership." However, when the vote was taken, Pollitt was defeated and was forced to resign as General Secretary. (39)

On 17th September, the Soviet Red Army invaded Eastern Poland, the territory that fell into the Soviet "sphere of influence" according to the secret protocol of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. On 6th October, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. Joseph Stalin now demanded not only Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, as part of the Soviet sphere. He aimed both to recover the land of the Russian Empire and to secure a compact area of defence for the Soviet Union. Hitler, unwilling to fight a war on two fronts, immediately accepted these terms. (40)

Primary Sources

(1) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Ida Chamberlain (26th March, 1939)

I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears. Moreover, she is both hated and suspected by many of the smaller States, notably by Poland, Rumania and Finland.

(2) On 16th April, 1939, the Soviet Union suggested a three-power military alliance with Great Britain and France. In a speech on 4th May, Winston Churchill urged the government to accept the offer.)

Ten or twelve days have already passed since the Russian offer was made. The British people, who have now, at the sacrifice of honoured, ingrained custom, accepted the principle of compulsory military service, have a right, in conjunction with the French Republic, to call upon Poland not to place obstacles in the way of a common cause. Not only must the full co-operation of Russia be accepted, but the three Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, must also be brought into association. To these three countries of warlike peoples, possessing together armies totalling perhaps twenty divisions of virile troops, a friendly Russia supplying munitions and other aid is essential.

There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge.

(3) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (19th May, 1939)

Undoubtedly, the proposals put forward by the Russian Government contemplate a triple alliance against aggression between England, France and Russia, which alliance may extend its benefits to other countries of and when those benefits are desired. The alliance is solely for the purpose of resisting further acts of aggression and of protecting the victims of aggression. I cannot see what is wrong with that. What is wrong with this simple proposal? It is said: "Can you trust the Russian Soviet Government?" I suppose in Moscow they say: "Can we trust Chamberlain?" I hope we may say that the answer to both questions is in the affirmative. I earnestly hope so.

Clearly Russia is not going to enter into agreements unless she is treated as an equal, and not only is treated as an equal, but has confidence that the methods employed by the Allies - by the peace front - are such as would be likely to lead to success. No one wants to associate themselves with indeterminate leadership and uncertain policies. The Government must realise that none of these States in Eastern Europe can maintain themselves for, say, a year's war unless they have behind them the massive, solid backing of a friendly Russia, joined to the combination of the Western Powers. In the main, I agree with Mr. Lloyd George that if there is to be an effective eastern front - an eastern peace front, or a war front as it might become - it can be set up only with the effective support of a friendly Soviet Russia lying behind all those countries.

(4) Time Magazine (15th May, 1939)

Officials may come and go with alarming frequency in most Government offices of the U.S.S.R., but not in the Soviet Foreign Commissariat. Amid all the shifts, purges and disappearances of Soviet officials, the Foreign Commissariat's topmost personnel has remained so constant that in 21 years since the proletarian revolution Soviet Russia has had only two Foreign Commissars: Georgy Vasilievich Chicherin, from 1918 to 1930 and Maxim Maximovich Litvinov, his successor.

Last week Comrade Litvinov's term abruptly ended, and with his displacement came Europe's sensation of the week. Moscow's radio laconically announced shortly before midnight one night that Comrade Litvinov had been relieved of his job at "his own request." The Commissar, it was explained later, was ill, had been suffering from heart disease. His job would henceforth be taken by Viacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov, President of the Council of People's Commissars, a member of the all-powerful Political Bureau of the Communist Party, right-hand man to Dictator Joseph Stalin for some 15 years.

Those who knew that Commissar Litvinov actually does take rest cures at Continental watering places for heart trouble might have accepted the Soviet "request" theory at its face value had it been made at any other time. But only 36 hours later Foreign Minister Josef Beck of Poland was to make an important reply to Adolf Hitler before the Polish Parliament. The British and French press were beginning to talk about "appeasing" the Germans again, at a time when the "Peace Front" was considering involved negotiations with the Soviet Union with a view to stopping Hitler.

Commissar Litvinov has never been much of a power inside the Soviet Union. He was not even a member of the Political Bureau and had been a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee for only five years. He probably did not even formulate Soviet Foreign policy; he was a brilliant diplomatic technician. But in the world's eyes he was identified with that era of Soviet policy when the U.S.S.R. backed up strongly every move to curb the aggressors, pushed forward the principles of collective security, allied itself with democracies, put its face squarely against dictatorships. Was that era to end? Last week all Europe guessed. Some of the guesses:

Most ominous - and least likely - explanation of the change: Comrade Stalin had decided to ally himself with Führer Hitler. Obviously Comrade Litvinov, born of Jewish parents in a Polish town (then Russian), could not be expected to complete such an alliance with rabidly Aryan Nazis.

More likely: the Soviet Union was going to follow an isolationist policy (almost as bad for the British and French). By turning isolationist it would let Herr Hitler know that as long as he keeps away from Russia's vast stretches he need not fear the Red Army. Russia might even supply the Nazis with needed raw materials for conquests.

Comrade Stalin still hankered after an alliance with Great Britain and France and by dismissing his experienced, alliance-seeking Foreign Commissar was simply trying to scare the British and French into signing up.

But the most likely explanation was that in the bluff and counter-bluff of present European diplomacy, Dictator Stalin was simply clearing the decks to be ready at a moment's notice to jump either way. Foreign Commissar Molotov, inexperienced in diplomacy, represents no fixed foreign policy. Chief claim to U. S. fame was his denunciation of Col. Charles A. Lindbergh as a "paid liar" for alleged slurs on Soviet aviation. Speaking German and French, he will still be able to talk turkey with the British-French "Peace Front." If these talks fail (as they were on the point of doing last week) he can turn to negotiations with the Dictators' front.

Whatever Comrade Litvinov's retirement meant, Britain and France thought it was bad news. It was accepted as good news in a Germany which had not failed to notice that, in his last two or three big speeches, Führer Hitler had dropped his usual tirade against the Bolsheviks. Whether it meant nothing or everything. Comrade Stalin had removed one of the smoothest, most accomplished actors from the world's diplomatic stage.

(5) Joachim von Ribbentrop Memoirs (1953)

To seek a settlement with Russia was my very own idea which I urged on Hitler because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict.

After a short ceremonial welcome the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and myself. Others present were our interpreter, Hilger, a great expert on Russian affairs, and a young fair-haired Russian interpreter, Pavlov, who seemed to enjoy Stalin's special trust.

Stalin spoke - briefly, precisely, without many words; but what he said was clear and unambiguous and showed that he, too, wished to reach a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin used the significant phrase that although we had 'poured buckets of filth' over each other for years there was no reason why we should not make up our quarrel.

(6) Sigrid Schultz, Chicago Tribune (13th July, 1939)

Communism, Soviet Russia and Dictator Stalin were called the arch enemies of civilization when Hitler was advancing toward supreme power. Hatred of communism and the faith of the bourgeois that he would save from communism helped him become master of Germany.

Today England is being proclaimed as World Enemy No.1. She is accused of usurping the rights of small nations, of opposing Germany's "right to be the first power in the world."

Hatred of England is simmering or blazing in Japan, India, Arabia, Africa, Ireland, Russia, and England's ally, France. It is being fanned systematically by Nazi agents throughout the world.

Hitler, it is said, hopes to use this hatred to establish Germany as the most powerful nation in the world, the same as he used the German citizen's hatred of communism to establish his rule in Germany.

Friendship with Soviet Russia, or at least an understanding with her, can prove a powerful weapon in Germany's campaign "to force England to her knees," diplomatic sources declare.

The Germans figure that the English are so terrified of the possible formation of a Soviet-German bloc that Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax will again go to Germany and offer all the concessions the Germans want. If the British fail to respond to the threat, the Germans argue that they can still get enough raw materials and money out of Russia to make the deal worth while.

(7) Time Magazine (28th August, 1939)

Late Sunday night - not the usual time for such announcements - the Soviet Government revealed a pact, not with Great Britain, not with France, but with Germany. Germany would give the Soviet Union seven-year 5% credits amounting to 200,000,000 marks ($80.000,000) for German machinery and armaments, would buy from the Soviet Union 180,000.000 marks' worth ($72,000,000) of wheat, timber, iron ore, petroleum in the next two years. And at Monday midnight the official German news agency announced from Berlin:

"The Government of the Reich and the Soviet Government have decided to conclude a non-aggression pact with each other. The Reichsminister of Foreign Affairs, von Ribbentrop, will arrive in Moscow on Wednesday to conclude the negotiations."

To the bewilderment of almost everybody else in the world, and the consternation of the non-totalitarian four-fifths of it, the announcement was confirmed in Moscow next morning. Russia had got into a peace pact, but not with the nations she had been doing the public dickering with.

A nightmare which the European democracies and their satellites only whispered about was the alliance of great Communist Russia with great Fascist Germany, a mighty cordon of non-democracy stretching one-third around the world from the Atlantic to the Pacific. There was no comfort in the hind seen reasons which made this Red & Black team if not inevitable, at least understandable:

1) Russia wanted as much peace as she could get, even at the expense of pulling her punches in Spain from 1938 on. If she joined the Allies, it might work out that she had merely balanced the European war scales; joining Germany tipped them, she could hope, to an imbalance the lighter side would not dare to challenge.

2) Russia, while suspicious of Germany, was suspicious of the democracies. Joseph Stalin having served notice in March that he did not propose to be pitted against Germany by the Allies, only so that both countries might be knocked out after each had knocked the other groggy.

3) Russia's rulers still smarted at being uninvited to Munich, where, according to high diplomatic humor, the democracies looked the totalitarians knowingly in the eye and nodded in the direction of the Ukraine.

4) Russia, and her raw materials, and Germany, and her industries, make an economic combination.

At any rate, if either Joseph Stalin or Adolf Hitler - who have led their countrymen to believe that the other is the devil unchained (but not so deliberately recently) - needed any sales points to make the deal palatable at home, they were available. General belief was that they would scarcely take the trouble. They did not even bother to reveal who had undertaken the preliminaries to the greatest and quietest diplomatic about-face in modern European history.

(8) Willy Brandt, Det Zoda Arhundre (January, 1940)

The attitude of the socialist movement towards the Soviet Union today must be considered against this background. Relations have changed almost beyond recognition. It is hardly a novel situation to find the leaders of the Soviet Union in a state of outright war against the socialist movement. It has happened before. But today the whole movement is obliged to stand up and fight, and draw a clear dividing line between itself and the Soviet Union. It is not the socialist movement but the Soviet Union which has changed. It is not the socialist movement but the Soviet Union which has entered a pact of friendship with Nazism. It is the Soviet Union which stabbed Poland in the back and initiated the war against Finland.

(9) William Joyce, Germany Calling (23rd June, 1941)

When in August, 1939, Hitler made a pact of friendship with Stalin, some of you may have wondered if Hitler had betrayed western civilisation. Yesterday in his proclamation, the Führer was able to speak openly for the first time. He said that it was with a heavy heart that he sent his Foreign Minister to Moscow. England left him no other choice. She had worked hard throughout the summer of 1939 to build up a coalition against Germany. Hitler was compelled in self-defence to conclude a pact of friendship with Russia in which the signatories agreed not to attack each other and defined spheres of interest.

(10) Nikita Khrushchev was the secretary of the Moscow Regional Committee in 1939. Khrushchev who was with Stalin when the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed, wrote about these events in his autobiography, Khrushchev Remembers (1971)

I believe the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of 1939 was historically inevitable, given the circumstances of the time, and that in the final analysis it was profitable for the Soviet Union. It was like a gambit in chess: if we hadn't made that move, the war would have started earlier, much to our disadvantage. It was very hard for us - as Communists, as anti-fascists - to accept the idea of joining forces with Germany. It was difficult enough for us to accept the paradox ourselves.

For their part, the Germans too were using the treaty as a maneuver to win time. Their idea was to divide and conquer the nations which had united against Germany in World War I and which might united against Germany again. Hitler wanted to deal with his adversaries one at a time. He was convinced that Germany had been defeated in World war I because he tried to fight on two fronts at once. The treaty he signed with us was his way of trying to limit the coming war to one front.

(11) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949)

In the course of two meetings in the Kremlin, on the evening of 23 August and late the same night, the partners thrashed out the main issues of "common interest" and signed a pact of non-aggression and a "secret additional protocol". Stalin could not have had the slightest doubt that the pact at once relieved Hitler of the nightmare of a war on two fronts, and that to that extent it unleashed the Second World War. Yet he, Stalin, had no qualms. To his mind the war was inevitable anyhow; if he had made no deal with Hitler, war wound still have broken out either now or somewhat later, under conditions incomparably less favourable to his country. His purpose now was to win time, time, and once again time, to get on with his economic plans, to build up Russia's might and then throw that might into the scales when the other belligerents were on their last legs.

(12) Time Magazine (4th September, 1939)

What Poland had to watch calmly last week (with not nearly enough gas masks to go around, due to the Government's all-for-the-Army emergency economy) was a succession of border intrusions, in which many observers saw true Nazi rhythm. From Germany, from East Prussia, even by air from Free Danzig, came Nazi "gangs" to provoke the alert Polish guards into brief scuffles from which four deaths resulted - extreme casualties of the war of nerves. At week's end the Polish radio, protesting that "the limit of Polish patience is very near," turned from straightforward reporting of developments to a satiric debunking of the provocative propaganda its people were hearing from over the border. One German radio report had it that a certain retired Polish Army captain had been leading forays against Germans in Poland. Polish officials investigated, found that the captain had been dead for two years. Commented the radio: "Such incidents could only, therefore, have been perpetrated by a ghost, for which the Polish authorities can hardly be held responsible."

(13) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

The announcement on August 23, 1939, that the Soviet Union and Germany had signed a non-aggression pact came like a thunderclap, not least of all to the communist movement. Leaders and rank-and-file members were thrown into utter confusion. The impossible had happened. We looked hopefully for an escape clause in the treaty, but the official text provided none. For several days there was no clarification from Moscow and we American Communists were left painfully on our own. It would have been better if we had remained on our own.

A national conference of the Communist Party had previously been scheduled for that weekend and it took place amid pathetic consternation. Eugene Dennis, then the party's legislative secretary and a member of the Political Bureau, the highest party committee, seemed to make the most sense, calling for a fight on two fronts: against the fascist enemy and against the appeasing democratic governments which could not be relied on to fight fascism. This attitude, a reasonable continuity with our former position, did not last long. Statements now began to come from Moscow - both from the Soviet press and the Communist International - which made clear a big change in policy was under way. When the Nazis now invaded Poland and Britain and France declared war against Germany, the Soviet position was that British and French imperialists were responsible for the war, that this was an imperialist war and that neither side should be supported.

The world communist movement followed in the wake of these statements. Until that moment the communist parties had been demanding that their governments fight against fascism; now that the West had at last declared war on the Axis, we denounced them and opposed all measures to prosecute the war. We demanded that the war be ended; how this could be done without the military defeat of Hitler was left unclear. Some communist leaders in the west, like Harry Pollitt, then general secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, projected a policy of working to establish governments that would energetically fight the fascists, but these leaders were removed. Now in disgrace, Pollitt went back to work as a boilermaker. Dennis did not persist in his original position, which had been similar to Pollitt's.

Actually, a good case could be made for the Soviet Union's non-aggression pact with Germany. For years Moscow had tried to reach an agreement with the West against fascism. Instead, the West had come to an agreement with fascism at Munich and behind the back of the Soviet Union. After Munich, the Soviet Union had every reason to believe that the West was not negotiating in good faith but was maneuvering to push Hitler into an attack upon the USSR. Convinced that Hitler was bent on war, unable to conclude a defensive alliance with the West, the Soviet Union decided to protect itself through a non-aggression pact. The West had only itself to blame for what happened. Churchill had warned the British government against such an eventuality. The Soviet Union undoubtedly gained temporary safety and additional time to prepare for the inevitable onslaught.

(14) Raymond Gram Swing, Good Evening (1964)

The British were busy all through early 1939 trying to negotiate an agreement with the Soviet Union. Even up to the stunning surprise of the Von Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, a success in the British negotiations was awaited. The Poles were against it; they wanted no truck with Moscow. But I thought the British-Soviet negotiations would succeed in spite of the Poles, and said so.

Now that this is all in the past, one sees that Stalin signed the pact with Hitler for two reasons, one being to partition a hostile Poland and annex a part of it, the other being to buy time to prepare for an attack Hitler might launch against the Soviet Union. This makes the perfidy of the Von Ribbentrop-Molotov pact no less venal, but perhaps a little less stupid than at first appeared. It would have served mankind far better for Stalin to have joined in deterring Hitler, instead of giving him the green light to make war. But when it comes to attributing blame for Hitler's war, France and Britain bear part of it for selling out Czechoslovakia at Munich.

Student Activities

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)