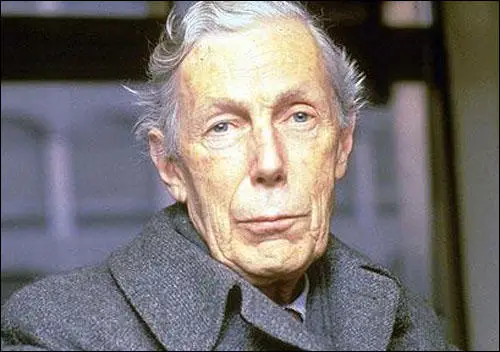

Dick White

Richard Goldsmith White, the youngest of three children of Percy Hall White, an ironmonger and agricultural engineer, was born in Tonbridge on 20th December, 1906. His father was a keen point-to-point rider: "He would dress up for the part, wearing his colours and hard hat and always neatly in trim. True or not, people used to say that my father was possibly one of the finest jockeys in Kent. I like to think that he taught me a good deal, more by example than anything else." (1)

According to his biographer: "White's early childhood was comfortable, but his father was over-ambitious in business and careless with money, and in 1913 the family endured a financial crash. White never forgot the shock of the sudden collapse into near penury. " (2) Percy Hall declined into impoverished and chronic alcoholism.

In 1917 he was sent to Bishop's Stortford College. He was an outstanding sportsman and in his final year he was captain of cricket, rugby and athletics. In 1925, he applied unsuccessfully to join the Royal Navy. White was however accepted to study history at Christ Church. There he came under the influence of John Masterman, a history tutor at the university. Masterman was a great influence on White and he gradually adopted his right-wing political views. In 1926 White took Masterman's advice and worked as a special constable during the General Strike. (3)

Eunan O'Halpin describes him during this period as "tall, slim, fair-haired, and blue-eyed, made his mark on college and university life as a man at once unassuming and accomplished... a good though not outstanding student, congenial rather than gregarious, he won a blue as a middle-distance runner". (4) However, he was deeply upset by Lionel Elvin, his Cambridge University competitor in the half-mile. Masterman claimed that his sporting achievements helped him "attain a position of importance among undergraduates... He is quite exceptionally respected by and popular among his contemporaries."

Dick White applied for a Commonwealth Fund Fellowship to study American history at a university in the United States. He received the award and won a place at the University of Michigan. White objected to the attitude of his fellow students, who he concluded were "immature and unintelligent". In conversation, "they voiced undisguised hostility to Britain's imperialism, especially in India, Palestine and Ireland". He especially disliked their moral rectitude: "Just look at the misdeeds of the American settlers against the indigenous Indians and Mexicans!" (5)

Dick White in America

White made friends with fellow student, Eric Linklater, who had been born in Wales but educated in Scotland. White drove with Linklater from Philadelphia to the Deep South. They then moved on to San Francisco. Linklater complained that White did not seem to be interested in the politics of the Great Depression: "Dick was a young man of hilarious temper... whose intellectual interests in 1929 seemed to be confined to Proust and the more blue-boltered periods in the history of Mexico." (6)

On his return to London Dick White attempted to find work as a journalist. Robert Barrington Ward , an assistant editor of The Times offered him a post in Manchester but he rejected the idea as he had no desire to work in the north. In 1931 Linklater introduced him to Janet Adam Smith, who worked for The Listener, and she arranged for him to review books for the magazine. The following year he found work teaching at the Whitgift School in Croydon: White was hired to teach history, English literature, French and German and to help with sport. The job was a compromise, but there was no alternative." (7) "There, it appeared, White had finally found his niche. He quickly made his mark both in the classroom and on the playing field as a gifted and compassionate teacher and an inspiring coach, and he seemed set fair for a career in education." (8)

MI5 Officer

In July, 1935, Dick White received a letter from Guy Liddell inviting him to lunch. At the meeting he told him that his former history tutor, John Masterman, had suggested that he would make a good member of MI5. White admits that he had never heard of the organization. This was not unusual as at this time MI5 was never mentioned in newspapers, in Parliament and the courts. To preserve officers' anonymity, and since the agency was not a legal entity established by statute, their pay was untaxed. The two men struck up a friendship and as a result White was appointed Liddell's assistant on a salary of £350 per year. On acceptance, White became MI5's thirtieth officer. (9)

Liddell was MI5's expert on subversive Bolshevik activities in trade unions, politics and the armed services. Liddell recognised that White possessed the essential qualities for an intelligence officer. "Not only natural intelligence, resourcefulness, self-motivation, patience, principle and patriotism, but also the ability to understand that, while service within MI5 was a team effort, much of the work would be solitary, depending upon his own judgment and self-confidence." Liddell wanted White to go to Nazi Germany to make an assessment of Adolf Hitler. "It seemed clear to me that fascism was a monumental threat and that something catastrophic was going to take place... I snapped at the bait. I could hardly resist. I saw the offer as a sort of early call-up for war service... I went to work for them under cover in Germany. In the end, I had no alternative but to stay." (10)

Dick White was sent to Germany in the guise of an advanced student on a nine-month tour of the country. "His task was to observe and to learn rather than to recruit agents or to spy. He perfected his German, and he obtained a valuable insight into the nature of the Nazi regime, while also experiencing the vicissitudes of operating under cover." (11) He was warned against running risks by "getting too close to defence establishments". White attended the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and watched the achievements of Jesse Owens, the American black athlete, who was considered an "inferior human being" by the Nazi regime but won four gold medals. White was horrified by the way the German people worshipped Hitler: "What appalled me most was the way in which decent Germans were falling for Hitler, hook, line and sinker. They had suddenly been brought back from inflation and unemployment. Suddenly everyone had a job. There is no doubt that it was as great a con as any people had ever been subjected to." (12)

On his return to England he worked closely with Maxwell Knight, B Division's expert on counter-subversion. White took an instant dislike to Knight who had been a member of British Fascisti (BF) in the 1920s . A fellow-agent, Joan Miller, pointed out: "The Communist threat was something about which M (Maxwell Knight) felt very deeply indeed; his views on this subject, you might say, amounted almost to an obsession. He was equally adamant in his aversion to Jews and homosexuals, but prepared to suspend these prejudices in certain cases. 'Bloody Jews' was one of his expressions (you have only to read the popular novels of the period - thrillers in particular - to understand just how widespread this particular prejudice was)." (13)

Dick White & German Agents

In 1937 Dick White became the case-officer of Jona von Ustinov, the former press officer at the German Embassy. He became friends with Robert Vansittart, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office. (14) Vansittart introduced Ustinov to Vernon Kell, the head of MI5 and he agreed to work for the secret service. Ustinov identified anti-Nazis in Germany that could be persuaded to become British agents. White described Ustinov as the "best and most ingenious operator I had the honour to work with... here, without question, we had picked a natural winner who wouldn't let us down." Ustinov found it difficult to deal with some members of the intelligence community who he described as being "ridiculously self-confident, irritatingly arrogant, seemingly well-informed and dismissive of anything that contradicted his prejudices". However, Ustinov developed a life-long friendship with White. (15)

Ustinov also recruited Wolfgang zu Putlitz, the First Secretary at the German Embassy, as a spy. According to Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "Vansittart put Kell in touch with Ustinov, doubtless intending the Security Service to use him as its point of contact with Putlitz. Ironically, in view of the fact that Vansittart listed homosexuality (along with Communism and Deutschism) as one of his three pet hates, Putlitz was gay; his partner, Willy Schneider, also acted as his valet." (16) Unknown to White, Putlitz, was also working for the NKVD.

In January 1939 White returned to Nazi Germany posing as an English teacher. Over the next few months he made contact with several opponents of Adolf Hitler including Dietrich Bonhoffer and Adam von Trot. "It was a question of resolution combined with hope, counter-balancing the Nazi enemies whom we all loathed and detested." (17) White attempted to recruit among the anti-Nazis who "looked to Britain as a moral force against fascism". White returned to London with details of Hitler's plans but was upset when the information was ignored by Neville Chamberlain: "Our material was decisive about Hitler's intentions, but Chamberlain ignored it." (18)

Walter Krivitsky

Walter Krivitsky, a former NKVD agent, escaped to the United States. In January 1940 he was brought to London. After meeting Major Stephen Alley he was taken to headquarters to be interviewed by Colonel Valentine Vivian and Brigadier Oswald Harker. The notes for the meeting was taken by Harker: "After a good deal of beating about the bush Krivitsky began to get down to facts and informed us that he was aware of the existence of an organization in the country for obtaining information. He was very anxious to point out that he himself was not responsible for the direction of activities against the UK, but was concerned wholly and solely during 1935, 1936 and 1937 with operations against Germany." (19)

Krivitsky was also interviewed by Dick White and Jane Archer. Krivitsky told them that the Soviet idea was "to grow up agents from the inside". Krivitsky added: "This method had a great disadvantage in that results might not be obtained for a number of years, but it was regularly used by Soviet Intelligence Services abroad. Krivitsky mentioned that the Fourth Department was prepared in some instances to wait for ten or fifteen years for results and in some cases paid the expenses of a university education for promising young men in the hope that they might eventually obtain diplomatic posts or other key positions in the service of the country of which they were nationals." (20)

Krivitsky told them that the NKVD had recruited a "Scotsman of good family, educated at Eton and Oxford, and an idealist who worked for the Russians without payment". The spy worked in the Foreign Office and "occasionally wore a cape and dabbled in artistic circles". (21) MI5 was later criticised for not identifying Donald Maclean from this description. White, like Archer, was sceptical. "He had never previously debriefed or handled a rival intelligence officer, nor had he any experience of Russia and its espionage organisations... While understanding the simplicities of the impending war between democracy and fascism, he was professionally unindoctrinated with knowledge of the profound ideological struggle between fascism and communism and of the NKVD's resulting ability to recruit non-Russian sympathisers as agents." White pointed out that MI5 was fixated on Britain's immediate predicament: "Our enemy was Germany, not Russia. Our major interest was whether Russia might help the Germans. Krivitsky provided no information about that." (22)

Second World War

The outbreak of the Second World War MI5 decided they would have to deal with Britain's 50,000 enemy aliens as potential fifth columnists, saboteurs and spies. Most were Jewish refugees but others were Germans and Italians opposed to their dictatorial governments. Vernon Kell, head of MI5, urged wholesale internment. White supported his superiors' conclusion: without mass internment, MI5's controls would collapse. (23) For the first two years of the war about 8,000 enemy aliens were temporarily interned in British camps.

During the opening few months of the war, under the supervision of Guy Liddell, MI5 recruited another 570 officers and staff. MI5 moved its headquarters to Wormwood Scrubs, a Victorian prison in London. "Inside the prison, the former cells became cramped offices. Their automatically locking doors with interior handles, small windows and lack of telephones offered a novel interpretation of security." During the Blitz a German bombing raid destroyed important MI5 records and most of the MI5's staff were moved to Blenheim Palace, whereas senior staff were transferred to 58 St James's Street in Mayfair. (24)

In early 1940 White travelled to France where he had meetings with officers working for the French intelligence agency. He was told that in France attempts were being made to persuade captured German agents to feed false information back to Germany. On his arrival back home White had discussions with Vernon Kell and it was agreed to establish a double-cross operation. John Masterman became chairman of the XX (Double-Cross) Committee. it attempted to "influence enemy plans by the answers sent to the enemy (by the double agents)" and to "deceive the enemy about our plans and intentions".

Arthur Owens, an agent working for Abwehr, was arrested and he eventually agreed to become a double-agent. Owen was White's first double-agent. As well as sending false information to Nazi Germany, Owens (codenamed SNOW) also kept White informed about the arrival of German agents in Britain. "Careful management of Snow and of other spies caught in 1939–40 saw the elaboration of the practice whereby captured agents were induced to feed back false and misleading information to Germany and to claim that they had built up networks of sub-agents and informers." (25) Between September and November 1940 a total of 21 German agents were arrested by Special Branch officers.

In May 1940 Winston Churchill became prime minister. Six months later he sacked Vernon Kell, Director-General of MI5, and replaced him with David Petrie. Over the next four years Petrie brought in experts to form sections for dealing with different types of agent. He also established closer links with MI6, the Secret Service with responsibility for counter-espionage outside Britain. Petrie's reforms particularly benefited White and Guy Liddell. As controllers of B division, they now managed MI5's most important operations. (26)

In May 1946 Sir Percy Sillitoe, the former chief constable of Sheffield and Glasgow, replaced David Petrie as head of MI5. Guy Liddell was expected to succeed David Petrie as chief of MI5. However, Ellen Wilkinson, who served under Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary, had heard rumours from Europe that Liddell was suspected of being a double-agent. As a result, Liddell did not get the top job and instead became Deputy-Director-General. (27)

Dick White and Kim Philby

In 1950 Stewart Menzies and John Sinclair discussed the possibility of Kim Philby becoming the next Director General of the MI6. Dick White, chief of MI5 counter-intelligence, was asked to produce a report on Philby. He instructed Arthur Martin and Jane Archer to carry out an investigation into his past. They became concerned about how quickly he changed from a communist sympathizer to a supporter of pro-fascist organizations. They also discovered that the description of the mole provided by Walter Krivitsky and Igor Gouzenko was close to that of Philby's time in Spain as a journalist. It was now decided that Philby could in fact be a double-agent. However, he was not recalled from America.

In May 1951, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean defected to the Soviet Union. Philby was suspected of tipping the two men off. On 12th June, Philby was interviewed by White. Philby later recalled: "He (White) wanted my help, he said, in clearing up this appalling Burgess-Maclean affair. I gave him a lot of information about Burgess's past and impressions of his personality; taking the line that it was almost inconceivable that anyone like Burgess, who courted the limelight instead of avoiding it, and was generally notorious for indiscretion, could have been a secret agent, let alone a Soviet agent from whom strictest security standards would be required. I did not expect this line to be in any way convincing as to the facts of the case; but I hoped it would give the impression that I was implicitly defending myself against the unspoken charge that I, a trained counter-espionage officer, had been completely fooled by Burgess. Of Maclean, I disclaimed all knowledge.... As I had only met him twice, for about half an hour in all and both times on a conspiratorial basis, since 1937, I felt that I could safely indulge in this slight distortion of the truth." (28)

White told Guy Liddell that he did not find Philby "wholly convincing". Liddell also discussed the matter with Philby and described him in his diary as "extremely worried". Liddell had known Guy Burgess for many years and was shocked by the news he was a Soviet spy. He now considered it possible that Philby was also a spy. "While all the points against him are capable of another explanation their cumulative effect is certainly impressive." Liddell also thought about the possibility that another friend, Anthony Blunt, was part of the network: "I dined with Anthony Blunt. I feel certain that Blunt was never a conscious collaborator with Burgess in any activities that he may have conducted on behalf of the Comintern." (29)

Prime Minister Winston Churchill became involved in the case and suggested that Kim Philby was interviewed again about the possibilities of him being a Soviet spy. This time he was cross-examined by Helenus Milmo, MI5's legal adviser and an experienced barrister. Milmo accused Philby of spying for the Soviets since the 1930s, sending hundreds of agents to their deaths, betraying Konstantin Volkov and tipping off Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean. Milmo pointed out that the volume of radio traffic between London and Moscow had jumped dramatically after Volkov's offer to defect, suggesting a tip-off to Moscow Centre, followed by a similar leap in traffic between Moscow and Istanbul.

The interrogation lasted for over four hours. In the next room, a posse of senior intelligence officers, including Dick White, Guy Liddell and Stewart Menzies. Liddell wrote in his diary: "The interrogation of Philby has been completed without admission, although Milmo is firmly of the opinion that he is or has been a Russian agent, and that he was responsible for the leakage about Maclean and Burgess... Philby's attitude throughout was quite extraordinary. He never made any violent protestation of innocence, nor did he make any attempt to prove his case." (30) Milmo reported to White: "I find myself unable to avoid the conclusion that Philby is and has been for many years a Soviet agent... There's no hope of a confession, but he's as guilty as hell." (31)

Director of MI5

Sir Percy Sillitoe eventually retired in 1953 and was replaced by Dick White. His biographer, Eunan O'Halpin, has argued this was a popular appointment: "This was widely welcomed within MI5 on account of his record, his personality, his high standing with the Americans, his good relations with Commonwealth intelligence services, and his understanding of Whitehall. He brought calm where there had been chaos, he secured the service's flank against attack from other departments, he was incisive and persuasive on paper and in person, and he commanded the confidence of ministers. He instituted a radical reorganization of MI5, including the creation of a separate personnel and recruitment division. He also secured Treasury approval for the long-overdue introduction of a proper career structure along civil-service lines. This enabled the service systematically to recruit and to retain good personnel." (32)

His major innovation was the creation of F Branch. This infiltrated every left-wing organization in Britain including the Labour Party, the trade unions, the peace movement and student unions. White appointed Alexander Kellar as the director of F Branch. Keller, a former president of the National Union of Students, suggested that MI5 should recruit British students and trade unionists. These people were then told to express views sympathetic to communism in the hope that they would recruited as Soviet agents. "Like wine, these long-term 'sleepers' would, White hoped, mature and progress up the ranks to work alongside other MI5 sources recruited inside the unions." (33)

David Maxwell-Fyfe, the home secretary, told White to "wage war on the communists and crypto-communists". In 1955 Hugh Winterton of MI5 organized the burglary of a flat occupied by a senior Communist Party official. Peter Wright, who took part in the operation, later recalled: "One of the F4 agent runners learned, from a source inside the Communist Party of Great Britain, that the entire Party secret membership files were stored in the flat of a wealthy Party member in Mayfair. A2 were called in to plan an operation to burgle the flat and copy the files." During the operation MI5 agents were able to photograph files detailing the party's entire 55,000 membership. (34)

Death of Buster Crabb

In April 1956, the Soviet leaders, Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin paid a visit on the battleship Ordzhonikidz, docking at Portsmouth. The visit was designed to improve Anglo-Soviet relations. Sir Anthony Eden, the prime minister, who had high hopes of establishing better relations and moderating the Cold War issued a precise directive to all services banning any intelligence operation of any kind against the Soviet leaders and the ship. (35)

The MI6 London station - run by Nicholas Elliott - decided that the visit was too good an opportunity to miss and ten days beforehand put up a list of six operations to MI6's Foreign Office adviser. "The Admiralty had been particularly keen to understand the underwater-noise characteristics of the Soviet vessels. The placing of a Foreign Office adviser inside MI6 was part of a drive to put the service on a somewhat tighter leash, but when an MI6 officer ambled into his office for a ten-minute chat about the plans, the adviser came away thinking they would then be cleared at a higher level (as some sensitive operations were) while Elliott and his colleagues assumed that the quick conversation constituted clearance." (36) When Eden heard about it he told MI6: "I am sorry, but we cannot do anything of this kind on this occasion." Elliott would later insist that the "operation was mounted after receiving a written assurance of the Navy's interest and in the firm belief that government clearance had been given". (37) Elliott also argued: "We don't have a chain of command. We work like a club." (38)

On 16th April 1956, the day before the cruiser was due to arrive, Buster Crabb and Bernard Smith, his MI6 minder, arrived in Portsmouth and registered with a local hotel. Against the rules of the SIS both men signed in their real names. Contrary to the fundamental rules of diving, that evening Crabb drank at least five double whiskys. By daybreak, the toxicity in his blood remained fatally high. (39)

The following morning Crabb dived into Portsmouth Harbour. "The main task was to swim underneath the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, explore and photograph her keel, propellers and rudder, and then return. It would be a long, cold swim, alone, in extremely cold and dirty water, with almost zero visibility at a depth of about thirty feet. The job might have daunted a much younger and healthier man. For a forty seven-year-old, unfit, chain-smoking depressive, who had been extremely drunk a few hours earlier, it was close to suicidal." (40) However, Elliott insisted that "Crabb was still the most experienced frogman in England, and totally trustworthy ... He begged to do the job for patriotic as well as personal motives." (41) Peter Wright, who worked for MI5 said that it was a typical piece of MI6 adventurism, ill-conceived and badly executed." (42)

Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011) has pointed out: "Where Bond battled the bad guys in the crystal-clear Caribbean, the diminutive Crabb plunged into the cold, muddy tide of Portsmouth Harbour just before seven in the morning. He had about ninety minutes of air and by 9.15 it was clear something had gone wrong. For a while, it looked like the whole affair might be hushed up. The MI6 officer went back to the hotel to rip out the registration page. The hotel owner went to the press, who sniffed a good story. The disappearance of a well-known hero could not be covered up." (43)

That night, James Thomas, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was dining with some of the Soviet visitors, one of whom asked, "What was that frogman doing off our bows this morning". According to the Russian, Crabb had been seen swimming at the surface at 7.30 a.m. by a Soviet sailor. (44) The commander-in-chief Portsmouth, denying knowledge of any frogman, assured the Russian there would be an Inquiry and hoped that all discussion had been terminated. With the help of the intelligence services, the Admiralty attempted to cover up the attempt to spy on the Russian ship. On 29th April the Admiralty announced that Crabb went missing after taking part in trials of underwater apparatus in Stokes Bay (a place five kilometres from Portsmouth).

The Soviet government now issued a statement announcing that a frogman was seen near the cruiser Ordzhonikidze on 19th April. This resulted in newspapers publishing stories claiming that Crabb had been captured and taken to the Soviet Union. Time Magazine reported: "... soon after anchoring, the Ordzhonikidze had taken the precaution of putting a crew of its own frogmen over the side. Had the Russian frogmen met their British counterpart in the quiet deep? Had Buster Crabb been killed then and there, or kidnapped and carried off to Russia? At week's end, the mystery of Frogman Crabb's fate remained as deep and impenetrable as the waters that surrounded so much of his life." (45) Nicholas Elliott claimed that he knew how Crabb died: "He almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or conceivably because some fault had developed in his equipment." (46)

Sir Anthony Eden, the British prime minister was furious when he discovered about the MI6 operation that had taken place without his permission. Eden pointed out in the House of Commons: "I think it is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." (47) Ten days later, Eden made another statement making it clear that his explicit instructions had been disobeyed. (48)

Eden forced the Diretor-General of MI6, Major-General John Sinclair, to take early retirement. He was replaced by Dick White, the head of MI5. As MI5 was considered by MI6 to be an inferior intelligence service, this was the severest punishment that could be inflicted on the organization. George Kennedy Young, a senior figure in MI6 defended the actions of Elliott. He argued that in "a world of increasing lawlessness, cruelty and corruption... it is the spy who has been called upon to remedy the situation created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests.. these days the spy finds himself the main guardian of intellectual integrity." (49)

Anthony Blunt

On 4th June 1963, Michael Straight was offered the post of the chairmanship of the Advisory Council on the Arts by President John F. Kennedy. Aware that he would be vetted - and his background investigated - he approached Arthur Schlesinger, one of Kennedy's advisers, and told him that Anthony Blunt had recruited him as a spy while an undergraduate at Trinity College. Schlesinger suggested that he told his story to the FBI. He spent the next couple of days being interviewed by William Sullivan. (50)

Straight's information was passed on to MI5 and Arthur Martin, the intelligence agency's principal molehunter, went to America to interview him. Michael Straight confirmed the story, and agreed to testify in a British court if necessary. Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) has argued that Straight's information was "the decisive breakthrough in MI5's investigation of Anthony Blunt". (51)

Peter Wright, who took part in the meetings about Anthony Blunt, argues in his book, Spycatcher (1987) that Roger Hollis decided to give Blunt immunity from prosecution because of his hostility towards the Labour Party and the damage it would do to the Conservative Party: "Hollis and many of his senior staff were acutely aware of the damage any public revelation of Blunt's activities might do themselves, to MI5, and to the incumbent Conservative Government. Harold Macmillan had finally resigned after a succession of security scandals, culminating in the Profumo affair. Hollis made little secret of his hostility to the Labour Party, then riding high in public opinion, and realized only too well that a scandal on the scale that would be provoked by Blunt's prosecution would surely bring the tottering Government down." (52)

Anthony Blunt was interviewed by Arthur Martin at the Courtauld Institute on 23rd April 1964. Martin later wrote that when he mentioned Straight's name he "noticed that by this time Blunt's right cheek was twitching a good deal". Martin offered Blunt "an absolute assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told the truth". Martin recalled: "He went out of the room, got himself a drink, came back and stood at the tall window looking out on Portman Square. I gave him several minutes of silence and then appealed to him to get it off his chest. He came back to his chair and confessed." He admitted being a Soviet agent and named twelve other associates as spies including Michael Straight, John Cairncross, Bernard Floud, Jenifer Hart, Phoebe Pool, Leo Long and Peter Ashby. (53) They were also given immunity from prosecution.

Arthur Martin was disappointed about the way Roger Hollis and the British government had decided not to put Anthony Blunt on trial. Martin once again began to argue that there was still a Soviet spy working at the centre of MI5 and that pressure should be put on Blunt to make a full confession. Hollis thought Martin's suggestion was highly damaging to the organization and ordered Martin to be suspended from duty for a fortnight. Martin offered to carry on with the questioning of Blunt from his home, but Hollis forbade it. As a result, Blunt was left alone for two weeks, and nobody knows what he did... Soon afterward, Hollis picked another quarrel with Martin, and though he was very senior, summarily sacked him. Martin believes that Hollis sacked him because he feared him, but his action did Hollis little good, whatever his motive." (54)

Peter Wright now took over the questioning of Blunt. He later recalled: "although Blunt... under pressure, expanded his information, it always pointed at those who were either dead, long since retired, or else comfortably out of secret access and danger". Wright asked him about Alister Watson, who he was convinced was a spy. Watson was still engaged in secret scientific work for the Admiralty. Blunt told Wright he could never be a Whittaker Chambers. "It's so McCarthyite, naming names, informing witch-hunts." Wright told him that his acceptance of the immunity deal obligated him to "play the role of Chambers". (55)

Wright arranged a joint meeting with Blunt. Wright tried to persuade Blunt to name Watson as a spy. He refused to do that, but when Wright suggested that he would be given immunity if he confessed, Watson turned to Blunt and said: "You've been such a success, Anthony, and yet it was I who was the great hope at Cambridge. Cambridge was my whole life, but I had to go into secret work, and now it has ruined my life."

Wright claims in his book, Spycatcher (1987): "No one who listened to the interrogation or studied the transcripts was in any doubt that Watson had been a spy, probably since 1938. Given his access to antisubmarine-detection research, he was, in my view, in particular, clinched the case. Watson told a long story about Kondrashev. He had met him, but did not care for him. He described Kondrashev in great detail. He was too bourgeois, claimed Watson. He wore flannel trousers and a blue blazer, and walked a poodle. They had a row and they stopped meeting."

Wright claims that this fits in with what the Soviet defector, Anatoli Golitsin, had told MI5. "He (Golitsin) said Kondrashev was sent to Britain to run two very important spies - one in the Navy and one in MI6. The MI6 spy was definitely George Blake... Golitsin said Kondrashev fell out with the Naval spy. The spy objected to his bourgeois habits, and refused to meet him. Golitsin recalled that as a result Korovin, the former London KGB resident, was forced to return to London to replace Kondrashev as the Naval spy's controller. It was obviously Watson." (56)

As John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), has pointed out: "The immunity deal was a convenient but flawed solution for all concerned. It was predicated on the assumption by MI5 that Blunt would live up to his side of the bargain. That he would provide the full and detailed confession that they needed. Once Blunt had been given the guarantee against prosecution, it would be impossible to bring him or any of those he implicated to justice. The price of uncovering the Cambridge network was that none of its members could ever be called to account." (57)

Dick White, the head of MI6, agreed with Martin that suspicions remained about the loyalty of Hollis and Mitchell. In November, 1964, White recruited him and immediately nominated Martin as his representative on the Fluency Committee, that was investigating the possibility of Soviet spies in British intelligence. The committee initially examined some 270 claims of Soviet penetration, which were later whittled down to twenty. It was claimed that these cases supported the claims made by Konstantin Volkov and Igor Gouzenko that there was a high-level agent in MI5. (58)

The people who Anthony Blunt named were interviewed by MI5. Jenifer Hart admitted being a member of the Communist underground but denied being a Soviet spy. Bernard Floud was interviewed by Peter Wright. After being interrogated he returned home and committed suicide on 10th October, 1967. Phoebe Pool, threw herself under a subway train, after being interviewed by Wright. Martin Furnival Jones, the director-general of MI5, was concerned that the suicides would "ruin our image" and brought and end to the investigation of Soviet spies named by Blunt. (59)

Dick White retired from the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in 1968. Maurice Oldfield was expected to be appointed but instead the appointment went to Sir John Rennie. White was appointed to the newly created post of co-ordinator of intelligence in the Cabinet Office. His biographer, Eunan O'Halpin, has argued: "The appointment of White to this novel position was not without its critics, and it is fair to say that only a man of his standing, tact, and judgement could have made a success of it without provoking monumental rows. White eschewed any temptation to turn the post into an overlordship of the various intelligence agencies or otherwise to throw his weight around, and instead concentrated on giving advice when asked. Some argue that this approach was tantamount to doing nothing at all, but there is no doubt that White's personal contribution was valued in the Cabinet Office." (60) He held this post to 1972.

Dick White died after a long illness at his home, The Leat, Burpham, near Arundel, on 21st February 1993.

Primary Sources

(1) Dick White, interviewed by Andrew Boyle for his book The Climate of Treason (1979)

I wasn't really cut out to be an intelligence officer at all. I partly stumbled into it for second-hand patriotic reasons and that suited the needs of my immediate superiors. At the start it only looked on as an experiment. That was why I went to work for them under cover in Germany. In the end, I had no alternative but to stay.

(2) Kim Philby, My Secret War (1968)

I could not claim White as a close friend but our personal and official relations had always been excellent, and he had undoubtedly been pleased when I superseded Cowgill. He was bad at dissembling but did his best to put our talk on a friendly footing. He wanted my help, he said, in clearing up this appalling Burgess-Maclean affair.

He (Dick White) was a nice and modest character, who would have been the first to admit that he lacked outstanding qualities. His most obvious fault was a tendency to agree with the last person he spoke to.

(3) When Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean fled to the Soviet Union in 1951 Kim Philby was interviewed by Dick White. Philby wrote about the interview in his book, My Secret War (1968)

Taking the line that it was almost inconceivable that anyone like Burgess, who courted the limelight instead of avoiding it, and was generally notorious for indiscretion, could have been a secret agent, let alone a Soviet agent from whom strictest security standards would be required. I did not expect this line to be in any way convincing as to the facts of the case; but I hoped it would give the impression that I was implicitly defending myself against the unspoken charge that I, a trained counter-espionage officer, had been completely fooled by Burgess. Of Maclean, I disclaimed all knowledge.... As I had only met him twice, for about half an hour in all and both times on a conspiratorial basis, since 1937, I felt that I could safely indulge in this slight distortion of the truth.

(4) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

Dick White, for all the elegance of his delivery, was essentially an orthodox man. He believed in the fashionable idea of "containing" the Soviet Union, and that MI5 had a vital role to play in neutralizing Soviet assets in the UK. He talked a good deal about what motivated a Communist, and referred to documents found in the ARCOS raid which showed the seriousness with which the Russian Intelligence Service approached the overthrow of the British Government. He set great store on the new vetting initiatives currently under way in Whitehall as the best means of defeating Russian Intelligence Service penetration of government.

(5) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995)

He (Dick White) was the anonymous director of an organisation governed by a three-page charter but without any status in law. This absence of legal status was an anomaly, setting MI5 apart from the security services of every other country in the world, whether democracy or dictatorship, but it was justified and even envied as a source of strength. Denied any legal powers, White was nevertheless authorised, in the interests of the nation's security, to pry into the affairs of every individual in the land. The limitations of his authority depended upon his own self-discipline, the animus of his political masters and his taking care to avoid public exposure. "I could only advise ministers on risks to security. The decision to take action was the politicians." Under his control were experts in - lock-picking, burglary, telephone-tapping, placing bugs, opening sealed letters, organising surveillance, photographing targets in compromising circumstances and blackmailers.

Improperly used, his signature - even his nod of approval - could disturb relationships, careers and lives without any redress for those afflicted. Although in theory his officers required signed authorisation to break into homes, eavesdrop and breach confidentialities, in practice he knew that there was a higher law: thou shall not get caught. Unaccountable to the public, MI5 understood that those in Whitehall whose job was to safeguard the national interest approved of MI5's surreptitious activities.

(6) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

Dick White never enjoyed good relations with Edward Heath. Their styles were so dissimilar. Dick worshipped Harold Macmillan, and the grand old man had a very high regard for his chief of Intelligence. Similarly, he got on well with Harold Wilson. They shared a suppleness of mind, and Wilson appreciated Dick's reassuring and comforting manner on vexed issues such as Rhodesia. But Heath was a thrusting, hectoring man, quite alien to anything Dick had encountered before, and he found himself increasingly unable to stamp his personality on the Prime Minister.

(7) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014)

To strengthen Elliott's hand, Dick White told him that new evidence had been obtained from the defector, Anatoly Golitsyn, although exactly what he revealed remains a matter of conjecture, and some mystery. Golitsyn had not specifically identified Philby as "Agent Stanley", but White gave Elliott the impression that he had. Was this intentional sleight of hand by White, allowing Elliott to believe that the evidence against Philby was stronger than it really was? Or did Elliott interpret as hard fact soiuething that had only been implied?

References

(1) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) pages 1-2

(2) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(3) John Masterman, On the Chariot Wheel (1975) pages 183-84

(4) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(5) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) pages 11-12

(6) Eric Linklater, Juan in America (1931) page 120

(7) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 17

(8) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(9) Nigel West, MI5: British Security Service Operations 1909-1945 (1983) page 51

(10) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) pages 23-24

(11) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(12) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) pages 27-28

(13) Joan Miller, One Girl's War (1970) page 66

(14) Christopher Andrew, Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985) page 541

(15) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 30

(16) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) page 196

(17) Francis H. Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979) page 7

(18) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 32

(19) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) pages 263-265

(20) Gary Kern, A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004) pages 247-256

(21) Andrew Boyle, The Climate of Treason (1979) page 200

(22) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 34

(23) Francis H. Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979) pages 30-32

(24) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 40

(25) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) pages 37-38

(26) Nigel West, MI5: British Security Service Operations 1909-1945 (1983) pages 191-192

(27) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(28) Kim Philby, My Secret War (1968) page 182

(29) Guy Liddell, diary (TNA KV 4/473)

(30) Guy Liddell, diary (TNA KV 4/473)

(31) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) page 427

(32) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(33) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 145

(34) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 54

(35) Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) page 65

(36) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 76

(37) Don Hale, The Final Dive (2007) page 172

(38) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 160

(39) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 73

(40) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 160

(41) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014) page 195

(42) Nicholas Elliott, With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994) page 25

(43) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 73

(44) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 76

(45) Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) page 65

(46) Time Magazine (14th May, 1956)

(47) Nicholas Elliott, With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994) page 25

(48) Anthony Eden, House of Commons (4th May, 1956)

(49) Anthony Eden, Full Circle (1960) page 365

(50) Roland Perry, Last of the Cold War Spies (2005) page 291

(51) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) page 436

(52) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 214

(53) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) page 437

(54) John Costello, Mask of Treachery (1988) page 590-594

(55) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 257 (47)

(56) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) pages 251-259

(57) John Costello, Mask of Treachery (1988) page 590

(58) Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) page 34

(59) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 266

(60) Eunan O'Halpin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)