Adam von Trott zu Solz

Adam von Trott zu Solz, the fifth child of the Prussian Culture Minister August von Trott zu Solz, was born in Potsdam, Germany on 9th August 1909. When his father resigned from office in 1917, the family moved to Kassel where von Trott attended the Friedrichsgymnasium. From 1922 he lived in Hann. He obtained his Abitur degree in 1927 and went on to study law at the universities of Munich and Göttingen. In 1931 he went to Mansfield College at Oxford University. (1)

In 1934 he began to practice law in Kassel. In 1937 he was employed by the American Institute of Pacific Relations on a project in China. In October 1938 Trott went to Washington to inform his friends there of the German Resistance. (2)

Trott believed that Neville Chamberlain should make it clear to Adolf Hitler that the appeasement policy was going to end. On 1st June, 1939, he arrived in London to have talks with British officials, including Edward Wood (Lord Halifax) and Philip Henry Kerr (Lord Lothian). According to Peter Hoffmann: At this time Trott was wondering whether he should leave Germany for the duration of the Nazi regime which he loathed, or whether he could fight the regime in some way." (3)

Formation of the Kreisau Circle

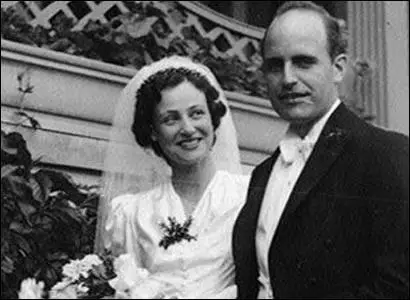

On the outbreak of the Second World War he went to work for the Foreign Office. He joined the Nazi Party as a cover for his resistance activities. Trott married Clarita Tiefenbacher in June 1940. The daughter of a prominent Hamburg lawyer she met him when they were working China. Clarita fully supported his resistance activities. Trott wrote during this period he became a rebel because "the divine destiny of man has been trampled down into the dust" and set his hopes on "the sense of decency of the individual citizen." (4)

In 1940 Trott, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke joined forces to establish the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who were ideologically opposed fascism. Other people who joined included Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Carlo Mierendorff, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Freya von Moltke, Theodor Haubach, Marion Yorck von Wartenburg, Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin, Dietrich Bonhoffer, Harald Poelchau and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (5)

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." (6) Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic." (7)

Members of the group came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the outlawed Social Democratic Party and the Church. "There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler." (8)

The group disagreed about several different issues. Whereas Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke were strongly anti-racist, others such as Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, believed that Jews should be eliminated from public service and evinced unmistakably anti-Semitic prejudice. "As late as 1938 he repeated his call for the removal of Jews from government and the civil service. His biographer, Albert Krebs, attests that he 'was never able to rid himself of feelings of alienation toward the intellectual and material world of Jewry.' He was appalled to learn of the crimes perpetrated against the Jewish population in the occupied Soviet Union, but this was not a major factor in his determination to see Hitler removed." (9)

Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) has argued that one of strengths of the Kreisau Circle was that it had no established leader: "It consisted of of highly independent personalities holding views of their own. They were both able and willing to compromise, for they knew that politics without compromise was impossible. In the discussion phase, however, they clung to their own views." (10) Although the Kreisau Circle did not have a leader, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke were the two most important figures in the group. Joachim Fest, the author of Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) has pointed out the Moltke has been described as the "engine" of the group, Wartenburg was its "heart". (11)

Adam von Trott became a very important member of the group. During the first winter of the war he began to think about the long-time future of Europe. He suggested that a European tariff and currency union, the setting up of a European Supreme Court and single European citizenship, as the basis for a future administrative unification of Europe. Moltke agreed and called for the setting up of a "supreme European legislature", which would be answerable, not to the national self-governing bodies, but to the individual citizens, by whom it would be elected. In other words, an European Parliament. (12)

Helmuth von Moltke agreed with Trott and expressed the expectation that "a great economic community would emerge from the demobilization of armed forces in Europe" and that it would be "managed by an internal European economic bureaucracy". Combined with this he hoped to see Europe divided up into self-governing territories of comparable size, which would break away from the principle of the nation-state. Although their domestic constitutions would be quite different from each other, he hoped that by the encouragement of "small communities" they would assume public duties. His idea was of a European community built up from below. (13)

Negotiations with the Allies

Adam von Trott also made several attempts to negotiate with the British government. In May 1942 along with Moltke he arranged for Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a member of the Kreisau Circle, and Hans Schönfeld, a fellow clergyman, to meet Bishop George Bell in Stockholm. Bonhoeffer and Schönfeld asked Bell: "Would the Allies adopt a different stance toward a Germany that had liberated itself from Hitler than they would toward a Germany still under his rule? Bell reported back to the British Foreign Office, but Anthony Eden wrote back only to say he was "satisfied that it is not in the national interest to provide an answer of any kind." A few months later, Bell approached the British Foreign Office again, Eden noted in the margin of his reply, "I see no reason whatsoever to encourage this pestilent priest!" (14)

The following year Helmuth von Moltke went to Stockholm with the latest leaflets being distributed by the White Rose resistance group. Adam von Trott and Eugen Gerstenmaier also went to the city to try and negotiate with representatives of the British government. Trott told them: "We cannot afford to wait any longer. We are so weak that we will only achieve our goal if everything goes our way and we get outside help." However, they received no encouragement. "The Allies did not even trouble themselves to reject the various attempts to contact them; they simply closed their eyes to the German resistance, acting as if it did not exist." (15)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Adam von Trott, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (16)

The July Plot to kill Adolf Hitler

Claus von Stauffenberg decided to carry out the assassination of Adolf Hitler. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany. (17)

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism." (18)

The conspirators eventually agreed who would be members of the government. Head of State: Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chancellor: Carl Goerdeler; Vice Chancellor: Wilhelm Leuschner; State Secretary: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg; State Secretary: Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin; Foreign Minister: Ulrich Hassell; Minister of the Interior: Julius Leber; State Secretary: Lieutenant Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg; Chief of Police: General-Major Henning von Tresckow; Minister of Finance: Johannes Popitz; President of Reich Court: General-Major Hans Oster; Minister of War: Erich Hoepner; State Secretary of War: General Friedrich Olbricht; Minister of Propaganda: Carlo Mierendorff; Commander in Chief of Wehrmacht: Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben; Minister of Justice: Josef Wirmer. (19)

On 22nd July, 1944, Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein met with two members of the underground Central Committee of the German Communist Party (KPD). "The meeting place was the house of a Berlin doctor, Rudolf Schmid... It was agreed that no names would be given and no introductions made; one of the communists who knew Leber, however, exclaimed:'Oh you, Leber.' Two of the visitors were in fact communist party functionaries, Anton Saefkow and Franz Jacob." In fact, a third communist turned up to the meeting. He was Hermann Rambow, who was in fact a Gestapo agent. The following day, Leber, Reichwein, Saefkow and Jacob were arrested. (20)

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (21)

Stauffenberg went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (22)

Stauffenberg observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. He got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let the car go. (23)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (24)

However, General Erich Fellgiebel, Chief of Army Communications, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. (25) Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead." (26) As a result, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, Ludwig Beck, Eugen Gerstenmaier, and Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg arrived at army headquarters in order to become members of the new government. (27)

Trials and Executions

Adolf Hitler had survived the blast. He was seized by a "titanic fury and an unquenchable thirst for revenge" ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (28)

Adam von Trott was arrested and tortured. His trial took place in front of by Roland Freisler on 15th August, 1944. Joseph Goebbels ordered that every minute of the trial should be filmed so that the movie could be shown to the troops and the civilian public as an example of what happened to traitors. (29) He was found guilty but his execution of the death sentence was postponed in order to extract further information: "Since Trott has undoubtedly withheld a great deal, the death sentence pronounced by the People's Court has not been carried out so that Trott may be available for further clarification." Adam von Trott zu Solz was executed at Ploetzwnsee Prison on 25th August, 1944. (30)

It is estimated that 4,980 people were arrested by the Gestapo. Heinrich Himmler gave instructions that these men should be tortured. He also ordered that family members should also be punished: "When they (the people's Germanic forbears) put a family under the ban and declared it outlawed or when there was a vendetta in the family, they were totally consistent about it. If the family was outlawed or banned; it will be exterminated. And in a vendetta they exterminated the entire clan down to its last member. The Stauffenberg family will be exterminated down to its last member." (31)

What became known as the Sippenhaft law (criminal liability of the next of kin to a person considered a criminal) was a particularly sophisticated form of torture. When interrogating suspects the Gestapo could, quite legally, threaten to ill-treat their wives, children, parents, brothers and sisters or other relatives. Under this law, Clarita Tiefenbacher was placed in custody in the Moabit prison in Berlin while her two daughters, aged respectively 2 years and nine months, were interned under false names in the SS-run children's home of Bornheim in Bad Sachsa (32)

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997)

Adam von Trott zu Solz studied at Oxford in 1932-33. Posted to China between 1937 and 1938, traveling by way of the United States. Used that trip and numerous others to establish contracts on behalf of the resistance, sometimes with exiled opponents of the regime. Joined the NSDAP in 1940 to provide a cover. Legation counselor in the Foreign Office's information division. Later worked in the India branch. Foreign policy adviser to the Kreisau Circle. Undertook further travels abroad in 1941 and 1943 to explore the Allied attitude toward a new German government but bitterly disappointed by the indifference of the Western Allies.

(2) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998)

The son of a former Prussian minister of education, Adam von Trott zu Solz had an American grandmother who was the granddaughter of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States. After early training at Kurt Hahn's school at Schloss Salem, he went in 1931 to Mansfield College, Oxford, and later entered Balliol as a Rhodes scholar. He returned to Germany in 1934 and began to practice law in Kassel. From the beginning Von Trott zu Solz opposed the Nazi regime. He was a member of the small Kreisau Circle, which hoped to overthrow the Nazis and restore Germany to the social ethic of Christianity.

(3) Anton Gill, An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994)

The name the Gestapo gave it (the Kreisau Circle) is misleading, for it gives the impression of an organised, coherent group, with definite aims. This is not true. The circle, which met formally at Kreisau only three times, was a large, loosely knit group of people who came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the old Social Democratic Party and the Church. Its membership shifted and changed, and for a long time its leaders were averse to taking action of any kind against Hitler, preferring instead to let him run his course - a matter which they considered inevitable - while in the meantime they discussed what sort of Germany they would rebuild after his equally inevitable fall...

There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler.

References

(1) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 354

(2) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 398

(3) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) pages 106-107

(4) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 354

(5) Louis R. Eltscher, Traitors or Patriots: A Story of the German Anti-Nazi Resistance (2014) page 298

(6) A. J. Ryder, Twentieth Century Germany: From Bismarck to Brandt (1973) page 425

(7) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 157

(8) Anton Gill, An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994) page 161

(9) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003) page 260

(10) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) page 192

(11) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 81

(12) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003) page 189

(13) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003) page 188

(14) Patricia Meehan, The Unnecessary War: Whitehall and the German Resistance to Hitler (1992) page 337

(15) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 209

(16) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 164

(17) Elfriede Nebgen, Jakob Kaiser (1967) page 184

(18) Roger Manvell, The July Plot: The Attempt in 1944 on Hitler's Life and the Men Behind It (1964) page 77

(19) Gerhard Ritter, German Resistance: Carl Goerdeler's Struggle Against Tyranny (1984) pages 368-371

(20) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) pages 363-364

(21) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) page 400

(22) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 258

(23) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) page 401

(24) Louis R. Eltscher, Traitors or Patriots: A Story of the German Anti-Nazi Resistance (2014) page 313

(25) Hans Gisevius, interviewed by Peter Hoffmann (8th September, 1972)

(26) Ian Kershaw, Luck of the Devil: The Story of Operation Valkyrie (2009) page 46

(27) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) page 272

(28) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964) page 1272

(29) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 750

(30) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) page 523

(31) Heinrich Himmler, speech (3rd August 1944)

(32) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977) page 520

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)