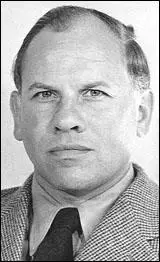

Eugen Gerstenmaier

Eugen Gerstenmaier was born in Kirchheim unter Teck on 25th August, 1906. He studied philosophy at Tübingen University. He continued his education in Rostock University, earning a doctorate in theology, and he was invited to remain as a lecturer. However, this offer was rescinded after an Nazi Party declared him as politically unreliable. (1)

In 1933, Martin Niemöller, complained about the decision by Adolf Hitler to appoint Ludwig Muller, as the country's Reich Bishop of the Protestant Church. With the support of Karl Barth, a professor of theology at Bonn University, in May, 1934, a group of rebel pastors, including Dietrich Bonhoffer, formed what became known as the Confessional Church. (2)

Gerstenmaier joined the Confessional Church but Hitler attempted to bring and end to this movement and in 1934 he was arrested by the authorities. He was released following an amnesty declared by President Paul von Hindenburg. (3) Gerstenmaier was released but many of its senior figures were sent to concentration camps, whereas others such as Karl Barth were deported. (4)

In 1935, he was appointed as assistant to Theodor Heckel the head of the field office of the German Evangelical Church. He then worked for the Information Section of the Foreign Office. He was in close contact with the Ecumenical Council in Geneva and the World Council of Churches, and its president, W. A. Visser't Hooft, who became an important figure in the resistance to Hitler. (5) He was also in contact with Richard Stafford Cripps, a leading Labour Party politician in Britain. (6)

In 1940 Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke joined forces to establish the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who opposed the Nazi Party. Eugen Gerstenmaier was introduced to the group by Adam von Trott. (7) Other members included Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Alfred Delp, Dietrich Bonhoffer and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (8)

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." (9) Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic." (10)

Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) has argued that one of strengths of the Kreisau Circle was that it had no established leader: "It consisted of of highly independent personalities holding views of their own. They were both able and willing to compromise, for they knew that politics without compromise was impossible. In the discussion phase, however, they clung to their own views." (11)

Gerstenmaier was one of the first members of the Kreisau Circle to accept that it was necessary to assassinate Hitler. He joined with Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg in a plot to kill Hitler. They decided to shoot Hitler while he was in Paris attending a parade on 20th July, 1940. On the appointed day Hitler failed to attend. According to Susan Ottaway, "because he realized that he had many enemies, he often changed his plans at the last moment". It may have been that he thought there would be more chance of something happening to him in an occupied country than in Germany. (12)

Gerstenmaier joined forces with Dietrich Bonhoffer, Adam von Trott, Hans Oster, and Hans Dohnanyi to enter negotiations with the British government, via Bishop George Bell. Gerstenmaier and Trott drafted a memorandum on the Europe after the war. At present, the memorandum said, destruction of human life and economic resources was on so vast a scale, after the war, even the victors would suffer from extreme poverty. "Owing to the pressures of war totalitarian control was increasing even in liberal countries; at the same time there was a tendency to anarchism and the abandonment of all established civilized standards... In the light of its own struggle, however, it felt justified in appealing to the solidarity of the civilized western world. The best way of expressing this solidarity was to refrain from decrying in public the statements and appeals of the German opposition." (13)

In April 1942, Trott gave this memorandum to W. A. Visser't Hooft, the president of the World Council of Churches, asking for it to be passed to Richard Stafford Cripps, the leader of the House of Commons. Cripps read the memorandum and was very attracted by it. He gave it to Winston Churchill who thought it "very encouraging". However, he did nothing about it. Five years after the war, Gerstenmaier, met Churchill at the Consultative Assembly on the Council of Europe, and reminded him of the memorandum. Churchill remembered it and regretted that he did not follow it up. (14)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (15)

Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg volunteered to assassinate Hitler. On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (16)

Stauffenberg went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (17)

Stauffenberg observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. He got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let the car go. (18)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (19)

However, General Erich Fellgiebel, Chief of Army Communications, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. (20) Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead." (21) As a result, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, Ludwig Beck and Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg arrived at army headquarters in order to become members of the new government. (22)

Adolf Hitler had survived the blast. He was seized by a "titanic fury and an unquenchable thirst for revenge" ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (23)

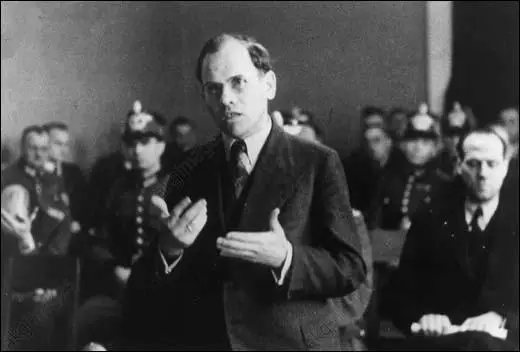

All the main members of the Kreisau Circle were arrested. This included Eugen Gerstenmaier who was beaten and tortured. (24) Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, Helmuth von Moltke, Adam von Trott, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Alfred Delp and Dietrich Bonhoffer were executed. However, in his trial on 11th January 1945, Gerstenmaier successfully portrayed himself as a "naive theologian baffled and bewildered by the world of politics" and was sentenced by Roland Freisler, the notorious Nazi judge, to seven years hard labour. (25)

Gerstenmaier was liberated from Bayreuth Penitentiary by American troops at the end of the Second World War. In 1945 Gerstenmaier took up a post in Stuttgart as head of the Aid Office of the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD). He became a politician in the Christian Democratic Party (CDU) and was president of the German Parliament from 1954 to 1969. (26)

Gerstenmaier was one of three candidates named to succeed Ludwig Erhard as Chancellor in 1966 but withdrew his nomination when the Christian Social Union, the Christian Democrats' sister party in Bavaria, threw its weight behind Kurt Georg Kiesinger. Three years later he stepped down as President of Parliament amid a scandal over compensation payments he received for a prewar teaching post he had never held. (27)

Eugen Gerstenmaier died on 13th March, 1986.

Primary Sources

(1) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003)

Eugen Gerstenmaier studied theology and philosophy, then in 1933-1934 took part in the defence of the churches against the Nazi-inspired 'German Christians'. He was briefly arrested by the Gestapo. From 1936 he worked in the External Affairs office of the Evangelical Church. This gave him an opportunity to travel abroad and he was soon regarded as an important helper by anti-Nazi groups. He was introduced to the Kreisau Circle by Adam von Trott.

(2) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997)

In May 1940 Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg resigned as regional commissioner in Silesia and joined his reserve regiment, because he believed that he could serve the resistance more effectively from within the army. Together with Eugen Gerstenmaier, a theologian and member of the Kreisau Circle, he attempted to form a commando unit to undertake Hitler's assassination. They failed, however, to assemble the nearly one hundred people required, and their plans were frustrated by transfers, orders to travel on official business at inopportune times, and Hitler's unpredictable changes of location.

(3) Susan Ottaway, Hitler's Traitors, German Resistance to the Nazis (2003)

In July 1940, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and fellow Kreisau Circle member, Eugen Gerstenmaier, decided to shoot Hitler while he was in Paris attending a parade. The parade was due to take place on 20 July and the two made their plans for the assassination. On the appointed day Hitler failed to attend. Perhaps because he realized that he had many enemies, he often changed his plans at the last moment and on this occasion he did just that... It may have been that he thought there would be more chance of something happening to him in an occupied country than in Germany.

(4) The New York Times (14th March, 1986)

Eugen Gerstenmaier, a former President of the Bonn Parliament, one of the founding fathers of West German democracy and an architect of conciliation with Israel, died today, sources close to his family said. He was 79 years old.

Jailed under the Nazis for involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler in 1944, Dr. Gerstenmaier became a leading member of the Christian Democratic Party after World War II and was President of the lower house of Parliament from 1954 to 1969.

Dr. Gerstenmaier was one of three candidates named to succeed Ludwig Erhard as Chancellor in 1966 but withdrew his nomination when the Christian Social Union, the Christian Democrats' sister party in Bavaria, threw its weight behind Kurt Georg Kiesinger.

Three years later he stepped down as President of Parliament amid a scandal over compensation payments he received for a prewar teaching post he had never held.

He gave up his parliamentary seat in 1969 but remained active in parliamentary and Protestant church organizations.

In the 1950's he campaigned for reconciliation with Israel and negotiated reparations payments to Israel that eased the bitterness toward Germany over the Holocaust and paved the way for normal relations between the two countries.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)