Claus von Stauffenberg

Claus von Stauffenberg, the youngest of three brothers, was born in Jettingen, on 15th November, 1907. His father was the Privy Chamberlain to the Maximilian, the King of Bavaria, and the last Oberhofmarschall of the Kingdom of Württemberg. His mother was granddaughter of the Prussian general August Wilhelm Anton Graf von Gneisenau. The Stauffenberg family was one of the oldest and most distinguished aristocratic Catholic families of southern Germany. (1)

As a young man Stauffenberg grew up under the influence of Catholicism - through his family were non-practising. He had a liberal education at the 250-year-old Eberhard Ludwig Grammar School in Stuttgart. Tall and very handsome, he was nevertheless prone to illness and was not physically strong. (2)

A devout Christian he found inspiration in the writings of the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas. Stauffenberg also became attracted to the ideas of Stefan George, a poet "then held in extraordinary esteem by an impressionable circle of young admirers, strangely captivated by his vague, neo-conservative cultural mysticism which looked away from the sterilities of bourgeois existence towards a new elite of aristocratic aestheticism, godliness, and manliness." (3)

A bright student, at nineteen Stauffenberg became an officer cadet. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has argued: "He (Claus von Stauffenberg) was a brilliant creature, with a passion not only for horses and outdoor sports but for literature and for music, at which he excelled. To his friends' surprise, he made the army his career." (4)

Claus von Stauffenberg: Early Military Career

In 1926 he joined the family's traditional regiment, the 17th Cavalry Regiment in Bamberg. Stauffenberg was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in 1930. His regiment eventually became part of the German 1st Light Division under General Erich Hoepner. According to his biographer, Louis L. Snyder: "A strikingly handsome young man, Claus was nicknamed the Bamberger Reiter because of his extraordinary resemblance to the famous thirteenth-century statue in the Cathedral of Bamberg." (5)

Theodore S. Hamerow argues that Stauffenberg was initially impressed with Adolf Hitler and like almost all other members of the officer corps, he found the new order vastly superior to the old. A friend who knew him in the early 1930s, reported after Hitler gained power he was delighted that "the people rose up against the chains of the Versailles Treaty... the misery of unemployment was eliminated through the creation of work, and other measures providing social relief for the working population were initiated." Another friend said that although Stauffenberg thought that Hitler, despite "all the low qualities in his nature" had expressed "fundamental and genuine longings for a revival". (6)

Stauffenberg began to have doubts about Hitler because his belief in the ideas of Stefan George. Hitler liked George's concepts of "the thousand year Reich" and "fire of the blood" and were adopted by the Nazi Party and incorporated into the party's propaganda. However, George detested their racial theories, especially the notion of the “Nordic superman” and when Joseph Goebbels offered him the presidency of a new academy for the arts, he refused, and went to live in exile in Switzerland. (7)

Stauffenberg married Nina Freiin von Lerchenfeld on 26th September 1933. Over the next few years they had five children (Berthold, Heimeran, Franz-Ludwig, Valerie and Konstanze). His wife explained how he gradually developed a hostility to Adolf Hitler but kept his true feelings hidden. "He let things come to him, and then he made up his mind ... one of his characteristics was that he really enjoyed playing the devil's advocate. Conservatives were convinced that he was a ferocious Nazi, and ferocious Nazis were convinced he was an unreconstructed conservative. He was neither." In fact he became a socialist but those who openly expressed these views were sent to concentration camps. (8) As another historian has explained: "Reared in a milieu of monarchist conservatism and Catholic piety, he later turned to the left in political thought and preferred a socialist society to that of the bourgeois Weimar Republic." (9)

Nazi Atrocities

Any sympathy he might have felt towards the regime withered, however, with the experience of Kristallnacht. According to Anton Gill, the author of An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994) "Stauffenberg's character seems to have been completely free of any racism whatsoever. He was, however, a professional soldier and he had not yet become politicised. Thoughts harboured against the National Socialist government now had to be shelved as Germany sped towards war. (10)

As a result of the Munich Agreement Stauffenberg's regiment moved into the Sudetenland. As this area contained nearly all Czechoslovakia's mountain fortifications, she was no longer able to defend herself against further aggression. Adolf Hitler ordered the German Army to enter Prague on 15 March 1939. Stauffenberg strongly disapproved of this action and feared it would result in an unnecessary war. He told a friend that "the fool is headed for war". Stauffenberg also believed it would take at least ten years to win the war. (11)

On the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 Claus von Stauffenberg and his regiment took part in the attack on Poland. He became concerned about the way the Poles were treated and began associating with Peter von Wartenburg who urged him to join the resistance against Hitler. Stauffenberg declined the invitation and in 1940 he was a member of the 6th Panzer Division that invaded France in May 1940. A brave soldier he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. (12)

In June, 1941, Stauffenberg took part in Operation Barbarossa. He was appalled by the atrocities committed by the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) in the Soviet Union. According to his friend, Major Joachim Kuhn, Stauffenberg told him in August 1942 that "They are shooting Jews in masses. These crimes must not be allowed to continue." Joachim Fest, the author of Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) has pointed out: "As a result of the massacres in the East, relations between Hitler and the officer corps, which had always been cool, despite a momentary reconciliation at the time of the great triumphs in France, began to deteriorate rapidly... It was at this time Stauffenberg resolved to do everything in his power to remove Hitler and overthrow the regime." (13)

Stauffenberg was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and sent to Africa to join the 10th Panzer Division as its Operations Officer in the General Staff. On 7th April 1943, Stauffenberg was wounded in the face, in both hands, and in the knee by fire from a low-flying Allied plane. According to one source: "He feared that he might lose his eyesight completely, but he kept one eye and lost his right hand, half the left hand, and part of his leg." Stauffenberg spent three months in a hospital in Munich, where his life was saved by the expert supervision of Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch. (14)

Resistance Movement

After he recovered it was decided that it would be impossible to serve on the front line and in October, 1943, he was appointed as Chief of Staff in the General Army Office. His commanding officer was General Friedrich Olbricht, who had already joined with Henning von Tresckow, Fabin Schlabrendorff and Hans Oster in the development of Operation Valkyrie, a General Staff plan which was ostensibly to be used to put down an attempted SS coup, but was really going to be used against Adolf Hitler. (15) Lieutenant-Colonel Stauffenberg joined the conspiracy that also included Ludwig Beck, Helmuth Stieff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Erich Hoepner, Mertz von Quirnheim, Werner von Haeften, Ulrich Hassell, Friedrich Fromm, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Peter von Wartenburg, Erwin von Witzleben, Johannes Popitz and Jakob Kaiser. (16)

The group was pleased by the arrival of Stauffenberg who brought new dynamism to the attempt to remove Hitler. Stauffenberg volunteered to be the man who would assassinate Hitler: "With the help of men on whom he could rely at the Führer's headquarters, in Berlin and in the German Army in the west, Stauffenberg hoped to push the reluctant Army leaders into action once Hitler had been killed. To make sure that this essential preliminary should not be lacking, Stauffenberg allotted the task of assassination to himself despite the handicap of his injuries. Stauffenberg's energy had put new life into the conspiracy, but the leading role he was playing also roused jealousies." (17)

The original plan, devised by General Major Tresckow, believed that only an assassination attempt at the Führer Headquarters could get round the unpredictability of Hitler's schedule and the tight security precautions surrounding him. They therefore needed to find a suicide bomber. The first person approached was Captain Axel von dem Bussche, He was a highly decorated captain and a supporter of Hitler until while at the Ukrainian town of Dubno, he witnessed the massacring of about 2,000 Jewish men, women and children. The victims were "herded along" and then were "compelled to strip and then to lie face downwards on top of the dead or still writhing Jews who had dug the pit and then been shot; the newcomers were then also killed by a shot in the nape of the neck. The SS men did all this in a calm, orderly fashion; they were clearly acting under orders." (18)

From that time on, Bussche, a committed Christian, dedicated himself to the task of doing whatever he could do destroy Hitler and all that he represented. There were, he said, only three possible ways for an honorable officer to react: to die in battle, to desert, or to rebel." (19) A lung injury resulted in him being invalided him out of active service. On his return to Germany he was put into contact with Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, a diplomat sympathetic to the resistance, who arranged for him to meet Stauffenberg. (20) When Stauffenberg asked him if he would be willing to kill Hitler, Bussche accepted without hesitation. After a brief discussion about the preferred method, they concluded that a bomb was the means most likely to succeed. A pistol shot might miss the mark or produce only a superficial wound. It was also believed that Hitler wore a bulletproof waistcoat. (21)

The occasion for the planned attack was a demonstration of new equipment and winter uniforms developed for use on the eastern front. Bussche agreed to be a model for one of the uniforms at a rally on 16th November, 1943, at the Wolfschanze at Rastenburg, where Hitler would be in attendance. He was a perfect choice for such a role. He looked "Nordic" and had served over the entire length of the eastern front. It was decided that Bussche should use a bomb with a five-second fuse. He planned to conceal the bomb in a deep pocket of the new uniform, and in the course of explaining its features, arm the bomb, and then jump on Hitler and throw him to the ground, holding him there for the few seconds required for the bomb to explode. Unfortunately, the rally was cancelled because the train in which the new uniforms were being transported was hit and destroyed by an Allied bomb the night before the proposed fashion show. (22)

Bussche was recalled to active service on the eastern front, but before he left Berlin he promised that he would be willing to carry out the assassination when the demonstration of new equipment and winter uniforms was re-scheduled. In January 1944, Stauffenberg contacted Bussche requesting his return. However, his divisional commander, who was not in the conspiracy, raised doubts about his battalion commanders acting as models for demonstrations of uniforms. A few days later Bussche was severely wounded and lost a leg and was unable to take part in the killing of Hitler. (23)

The Major General Helmuth Stieff was the only conspirator who was able to attend the demonstration of new uniforms. Stieff had recently declared himself ready to assassinate Hitler, but, when Stauffenberg asked him to carry out the killing, he backed out. Stauffenberg now approached Lieutenant Ewald Heinrich von Kleist and asked him to carry out the task. He asked for his father's opinion, who replied: "You have to do it. Anyone who falters at such a moment will never again be one with himself in this life." However, he decided against taking such action. (24)

1944 July Plot

Stauffenberg now decided to carry out the assassination himself. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany. (25)

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism." (26)

Peter Hoffmann has argued: "On Goerdeler's insistence he agreed that Goerdeler should be the main negotiator with Leber, Leuschner and their representatives. Goerdeler had already written a letter to Stauffenberg, transmitted through Kaiser, protesting against Stauffenberg negotiating independently with trade union leaders and socialists... This meant that Goerdeler should play the leading role in all non-military questions, as Beck was still insisting as late as July 1944. This he did not so much from suspicion of Stauffenberg as from aversion to exaggerated concentration of power. Moreover Stauffenberg was politically inexperienced; his views were vague; goodwill and idealism by themselves generally only do damage in politics. The fact that he was risking his life did not give Stauffenberg the right to claim power of political decision; Goerdeler and Beck were risking their lives too. The ability to murder Hitler was no adequate justification for assuming the role of political leader." (27)

To carry out the assassination, it was necessary for Stauffenberg to have access to Adolf Hitler. One member of the group, General Friedrich Fromm was Commander in Chief of the Reserve Army. His was in charge of training and personnel replacement for combat divisions of the German Army and had regular meetings with Hitler. It was agreed that a close friend of General Rudolf Schmundt, Hitler's chief adjutant, should suggest that Stauffenberg should become chief of staff to General Fromm. According to Albert Speer, "Schmundt explained to me, Stauffenberg was considered one of the most dynamic and competent officers in the German army. Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg. In spite of his war injuries (he had lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers of his left hand), Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic and at the same time precise, thus showing the marks of the two major and seemingly incompatible educational influences upon him: the circle around the poet Stefan George and the General Staff. He and I would have hit it off even without Schmundt's recommendation." (28)

On 1st July 1944 Stauffenberg was promoted to Colonel and became Chief of Staff to Fromm. Stauffenberg was now in a position where he would have regular meetings with Adolf Hitler. Fellow conspirator, Henning von Tresckow sent a message to Stauffenberg: "The assassination must be attempted, at any cost. Even should that fail, the attempt to seize power in the capital must be undertaken. We must prove to the world and to future generations that the men of the German Resistance movement dared to take the decisive step and to hazard their lives upon it. Compared with this, nothing else matters." (29)

Stauffenberg attended his first meeting with Hitler on 6th July. He had a bomb with him but for reasons that to this day are not entirely clear, he did not try to kill Hitler. The generally accepted theory is that Stauffenberg was dissuaded from acting because neither Heinrich Himmler or Hermann Göring were present. Several conspirators, including General Ludwig Beck, wanted these two men killed at the same time as Hitler. The theory being that Göring and Himmler would take power after the death of Hitler. (30)

On 11th July, Stauffenberg flew once more to Hitler's headquarters in Berchtesgaden. He had a bomb with him but did not set it off because Himmler and Göring were not at the meeting. According to Peter Hoffmann: "There was never any certainty that Himmler or Göring would be present at the briefing conferences; neither of them attended regularly. They were usually represented by their liaison officers who reported to them; they themselves came comparatively seldom. Sometimes Himmler and Göring had no personal contact with Hitler for weeks; at other times one of the other would attend several conferences with Hitler daily." (31) Stauffenberg remained committed to trying to kill Hitler although he had little confidence he would be successful. On 14th July he was quoted as saying: "The worst thing is knowing that we cannot succeed and yet that we have to do it, for our country and our children." (32)

Claus von Stauffenberg had another meeting with Adolf Hitler on 15th July. Although he had the bomb with him he did not take this opportunity to kill Hitler. The main reason was probably the difficulty he would have had in fusing his bomb. Since he only had three fingers on one hand he had to use a pair of pliers and this would certainly have been seen. It has been claimed that if he had bent down "to his briefcase and began to open it with his three fingers - someone would certainly have come to his assistance, lifted it on to the table and helped him take out the papers - impossible then to search round for the pliers, squeeze the fuse and put the briefcase back on the floor." (33)

Stauffenberg needed help in his task and his adjutant, Werner von Haeften, agreed to help assassinate Hitler, when he told his brother, the diplomat, Hans-Bernd von Haeften, also a member of the conspiracy, he raised objections on religious grounds. For sometime he had become entangled in a web of philosophical and religious reflection. He asked Werner: "Are you absolutely sure this is your duty before God and our forefathers?" Werner replied that the act was justified because it would bring an end to the war and would therefore save the lives of many Germans. (34)

Stauffenberg was now convinced that he was morally justified in taking this action. His religious and ethical beliefs led him to the conclusion that it was his duty to eliminate Hitler and his murderous regime by any means possible. Just before he left on his mission to kill Hitler he said: "It is now time that something was done. But he who has the courage to do something must do so in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor. If he does not do it, however, he will be a traitor to his conscience." (35)

Other members of the conspiracy also urged action. Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, who had been an integral part of the resistance from the beginning, continued to argue that the attempt must be made, regardless of the consequences. As Theodore S. Hamerow pointed out: "Some of those involved in planning the coup started to suggest that the attempt to overthrow the Nazi regime must be made not primarily to save Germany but as an act of atonement or expiation. Even if it should fail, even if the fatherland should be conquered and occupied, the resistance must wage its struggle against National Socialism as a moral obligation, as a sacrifice for mankind, as an appeal for forgiveness and redemption... What mattered was proving to the world that at least some Germans, acting out of conscience and in accordance with universal moral values, were willing to sacrifice themselves to protect humanity against an unspeakable evil." (36)

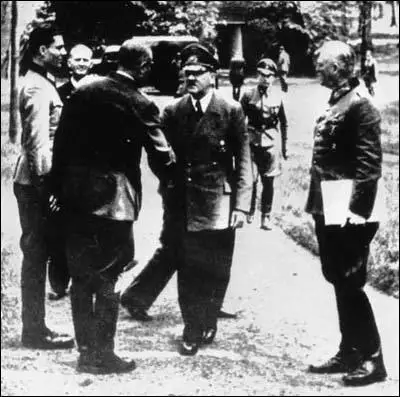

to attention next to Fromm. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, with folder, looks on.

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg and Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived." (37)

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (38)

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (39)

Stauffenberg and Haeften observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. They got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let them go. (40)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (41)

The original plan was for Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm to take control of the German Army. However, General Erich Fellgiebel, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. (42)

Stauffenberg arrived back in Berlin and went straight to see General Friedrich Fromm. Stauffenberg insisted that Hitler was dead. Fromm replied that he had just learnt from Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel that Hitler had survived the bomb attack. Stauffenberg replied, "Field Marshal Keitel is lying as usual. I myself saw Hitler being carried out dead." He then admitted that he had planted the bomb himself. Fromm became very angry and declared that all the conspirators were under arrest, whereupon Stauffenberg retorted that, on the contrary, they were in control and he was under arrest. (43)

Shortly after the assassination attempt, Joseph Goebbels broadcast a communiqué over German radio, assuring the public that Hitler was alive and well and that he would speak to the nation later that evening. Goebbels began the broadcast with the following words: Today an attempt was made on the Führer's life with explosives... The Führer himself suffered no injuries beyond light burns and bruises. He resumed his work immediately." (44)

Albert Speer, minister of armaments, visited Goebbels soon after the broadcast. He described the scene outside: "The office windows looked out on the street. A few minutes after my arrival I saw fully equipped soldiers, in steel helmets, hand grenades at their belts and submachine guns in their hands, moving toward the Blandenburg Gate in small, battle ready groups. They set up machine guns at the gate and stopped all traffic. Meanwhile, two heavily armed men went up to the door along the park and stood guard there." However, Goebbels was not confident that he would not be arrested and carried with him some potassium cyanide capsules. (45)

Goebbels was safe because the July 1944 Plot had been so badly organized. No real attempt had been made to arrest the Nazi leaders or to kill them. Nor did they secure immediate control of the radio and telephone communications systems. This was surprising as weeks earlier the original plan included the seizure of the long-distance telephone office, the main telegraph office, the radio broadcasting facilities in and around Berlin, and the central post office. "Incomprehensibly, the conspirators did not carry out these actions with sufficient dispatch, and this produced utter and fatal confusion." (46)

Later that day, Goebbels told Heinrich Himmler: "If they hadn't been so clumsy! They had an enormous chance. What dolts! What childishness? When I think how I would have handled such a thing. Why didn't they occupy the radio station and spread the wildest lies? Here they put guards in front of my door. But they let me go right ahead and telephone the Führer, mobilize everything! They didn't even silence my telephone. To hold so many trumps and botch it - what beginners!" (47)

Sometime between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m., the cordon that the conspirators had established around the government quarter was lifted. Military units that initially had supported the conspirators were switching loyalties back to the Nazis. The main reason for this was the series of radio announcements that were broadcast throughout Germany. By 10.00 p.m., forces loyal to the government were able to seize control of central headquarters and General Friedrich Fromm was released and Stauffenberg and his followers were taken prisoner. (48)

Those arrested included Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General Friedrich Olbricht, Colonel Mertz von Quirnheim and Lieutenant Werner von Haeften. Fromm decided that he would hold an immediate court-martial. They were all found guilty and sentenced to death. Hoepner, an old friend, was spared to stand further trial. Beck requested the right to commit suicide. According to the testimony of Hoepner, Beck was given back his own pistol and he shot himself in the temple, but only managed to give himself a slight head wound. "In a state of extreme stress, Beck asked for another gun, and an attendant staff officer offered him a Mauser. But the second shot also failed to kill him, and a sergeant then gave Beck the coup de grâce. He was given Beck's leather overcoat as a reward." (49)

The condemned men were taken to the courtyard. Drivers of vehicles parked in the courtyard were instructed to position them so that their headlight would illuminate the scene. General Olbricht was shot first and then it was Stauffenberg's turn. He shouted "Long live holy Germany." The salvo rang out but Haeften had thrown himself in front of Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg. Quirnheim was the last man shot. It was 12.30 a.m. (50)

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Goerdeler had doubts about Claus von Stauffenberg when he joined the German Resistance in 1942.

Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism.

(2) Henning von Tresckow, message to Claus von Stauffenberg (July, 1944)

The assassination must be attempted, at any cost. Even should that fail, the attempt to seize power in the capital must be undertaken. We must prove to the world and to future generations that the men of the German Resistance movement dared to take the decisive step and to hazard their lives upon it. Compared with this, nothing else matters.

(3) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

General Schmundt, Hitler's chief adjutant, had picked Count Stauffenberg to serve as Fromm's chief of staff and to inject some force into the work of the flagging general. As Schmundt explained to me, Stauffenberg was considered one of the most dynamic and competent officers in the German army. Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg. In spite of his war injuries (he had lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers of his left hand), Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic and at the same time precise, thus showing the marks of the two major and seemingly incompatible educational influences upon him: the circle around the poet Stefan George and the General Staff. He and I would have hit it off even without Schmundt's recommendation. After the deed which will forever be associated with his name, I often reflected upon his personality and found no phrase more fitting for him than this one of Holderlin's :"An extremely unnatural, paradoxical character unless one sees him in the midst of those circumstances which imposed so strict a form upon his gentle spirit."

There were further sessions of these conferences on July 6 and 8. Along with Hitler, Keitel, Fromm, and other officers sat at the round table by the big window in the Berghof salon. Stauffenberg had taken his seat beside me, with his remarkably plump briefcase. He explained the Valkyrie plan for committing the Home Army. Hitler listened attentively and in the ensuing discussion approved most of the proposals. Finally, he decided that in military actions within the Reich the military commanders would have full executive powers, the political authorities - which meant principally the Gauleiters in their capacity of Reich Defense Commissioners-only advisory functions. The military commanders, the decree went, could directly issue all requisite instructions to Reich and local authorities without consulting the Gauleiters.

Whether by chance or design, at this period most of the prominent military members of the conspiracy were assembled in Berchtesgaden. As I know now, they and Stauffenberg had decided only a few days before to attempt to assassinate Hitler with a bomb kept in readiness by Brigadier General Stieff. On July 8, I met General Friedrich Olbricht to discuss the drafting of deferred workers for the army; up to now Keitel and I had been at odds over this question. As so often. Olbricht complained again about the difficulties that inevitably arose from the armed forces being split into four services. Were it not for the jealousies of the different branches, the army could avail itself of hundreds of thousands of young soldiers now in the air force, he said.

The next day, I met Quartermaster General Eduard Wagner at the Berchtesgadener Hof, along with General Erich Fellgiebel of the Signal Corps, General Fritz Lindemann, aide to the chief of staff, and Brigadier General Helmut Stieff, chief of the Organizational Section in the High Command of the Army (OKH). They were all members of the conspiracy and none of them was destined to survive the next few months. Perhaps because the long-delayed decision to attempt the coup d'etat had now been irrevocably taken, they were all in a rather reckless state of mind that afternoon, as men often are after some great resolution. My Office Journal records my astonishment at the way they belittled the desperate situation at the front: "According to the Quartermaster General, the difficulties are minor.... The generals treat the eastern situation with a superior air, as if it were of no importance."

(4) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

Stauffenberg flew from Berlin during the morning and was expected to report on the creation of new Volksgrenadier divisions. He brought his papers with him in a brief-case in which he had concealed the bomb fitted with a device for exploding it ten minutes after the mechanism had been started. The conference was already proceeding with a report on the East Front when Keitel took Stauffenberg in and presented him to Hitler. Twenty-four men were grouped round a large, heavy oak table on which were spread out a number of maps. Neither Himmler nor Goring was present. The Fuhrer himself was standing towards the middle of one of the long sides of the table, constantly leaning over the table to look at the maps, with Keitel and Jodl on his left. Stauffenberg took up a place near Hitler on his right, next to a Colonel Brandt. He placed his brief-case under the table, having started the fuse before he came in, and then left the room unobtrusively on the excuse of a telephone call to Berlin. He had been gone only a minute or two when, at 12.42 p.m., a loud explosion shattered the room, blowing out the walls and the roof, and setting fire to the debris which crashed down on those inside.

In the smoke and confusion, with guards rushing up and the injured men inside crying for help, Hitler staggered out of the door on Keitel's arm. One of his trouser legs had been blown off; he was covered in dust, and he had sustained a number of injuries. His hair was scorched, his right arm hung stiff and useless, one of his legs had been burned, a falling beam had bruised his back, and both ear-drums were found to be damaged by the explosion. But he was alive. Those who had been at the end of the table where Stauffenberg placed the brief-case were either dead or badly wounded. Hitler had been protected, partly by the table-top over which he was leaning at the time, and partly by the heavy wooden support on which the table rested and against which Stauffenberg's brief-case had been pushed before the bomb exploded.

(5) Anne Frank, diary (21st July, 1944)

I'm finally getting optimistic. Now, at last, things are going well! They really are! Great News! An assassination attempt has been made on Hitler's life, and for once not by Jewish Communists or British capitalists, but by a German general who's not only a count, but young as well. The Fuhrer owes his life to "Divine Providence" he escaped, unfortunately, with only a few minor burns and scratches. A number of officers and Generals who were nearby were killed or wounded. The head of the conspiracy has been shot.

This is the best proof we've had so far that many officers and generals are fed up with the war and would like to see Hitler sink into a bottomless pit, so they can establish a military dictatorship, make peace with the Allies, rearm themselves and, after a few decades, start a new war. Perhaps Providence is deliberately biding its time getting rid of Hitler, since it's much easier, and cheaper, for the Allies to let the impeccable Germans kill each other off. It's less work for the Russians and British, and it allows them to start rebuilding their own cities that much sooner. But we haven't reached that point yet, and I'd hate to anticipate the glorious event

(6) Adolf Hitler to Joachim von Ribbentrop (20th July, 1944)

I will crush and destroy the criminals who have dared to oppose themselves to Providence and to me. These traitors to their own people deserve ignominious death, and this is what they shall have. This time the full price will be paid by all those who are involved, and by their families, and by all those who have helped them. This nest of vipers who have tried to sabotage the grandeur of my Germany will be exterminated once and for all.