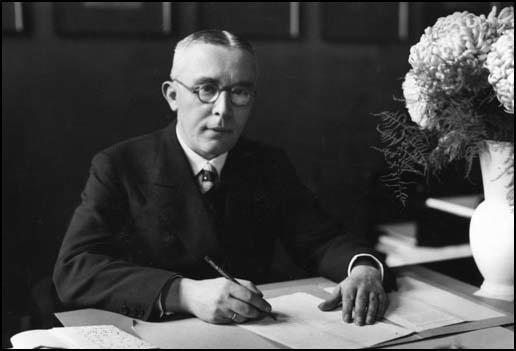

Johannes Popitz

Johannes Popitz, the son of a pharmacist, was born in Liepzig, on 2nd December 1884. A brilliant scholar, he studied law, economics and political science and embarked on a highly successful career in legal administration. In 1907 he acted as a junior government lawyer. (1)

In 1918, he married Cornalia Slot with whom he had three children. In 1919, after the election for the Weimar National Assembly, he became a Geheimrat in the finance ministry. In 1922 he became professor of tax law and financial science at the University of Berlin. He held very conservative views and in one article he wondered whether a legislative structure based on universal suffrage could provide adequate representation for those taxpayers who must bear the heaviest burden. (2)

From 1925 to 1929, Popitz acted as State Secretary in the German Ministry of Finance, where he worked under Finance Minister Rudolf Hilferding, a member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), but resigned in 1929, owing to political differences with the government. He was also a member of the Wednesday Club, a small group of right-wing conservatives, composed of academics, industrialists and civil servants. They met every Wednesday in Berlin to discuss, history, economics and politics. At one meeting Popitz expressed the view that it was necessary to establish a governing class. (3)

Johannes Popitz and the Corporate State

On 21st April 1933, Adolf Hitler appointed Popitz as Minister without Portfolio and Reich Commissioner for the Prussian Ministry of Finance. He welcomed Hitler's dictatorship because Germany's economic problems had been caused by the "parliamentary democratic method". This meant first of all that the dominant influence molding economic development originated in "the interests of the parties" in "compromises made by parliamentary coalitions". Popitz was therefore the main proponent of the corporate state. (4) Hitler had so much respect for Popitz that he awarded him the Nazi Party award of the Golden Badge of Honor. (5)

Popitz was a close friend of Kurt von Schleicher, who had been chancellor of Germany (December 1932 – January 1933) and a close associate of President Paul von Hindenburg. Hitler became convinced that Schleicher was involved in a conspiracy to overthrow the Nazi regime and during the Night of the Long Knives, the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) were sent to murder him and his young wife on 30th June 1934. It is believed that after this killing Popitz had grave doubts about Hitler. (6)

In a meeting with the diplomat, Ulrich von Hassell, in September, 1938, Popitz declared his opposition to Hitler: "Popitz was extremely bitter: he was of the opinion that the Nazis will proceed with increasing fury against the 'upper strata' as Hitler calls it. The danger of this tendency is enormous since Hitler has started including senior officers ('the cowardly mutinous generals') in those he rejects. Every decent person is seized by physical nausea, as the acting Minister of Finance Popitz expressed it, when he hears speeches like Hitler's recent vulgar tirade in the Sports Palace." (7)

Popitz shared views on the problems caused by the Jews: "As somebody who was very familiar with conditions in the Weimar Republic, my view of the Jewish question was that the Jews ought to disappear from the life of the state and the economy. However, as far as the methods were concerned, I repeatedly advocated a somewhat more gradual approach, particularly in light of diplomatic considerations." (8)

After Kristallnacht on 9th November 1938, Popitz protested the mass persecution of Jews by tendering his resignation to Hermann Göring, who promised to forward to Hitler. Popitz said he felt it necessary to take this action at least because those responsible, Cabinet ministers like Konstantin von Neurath and Franz Gürtner, "had once again failed ignominiously" (9) Although Popitz despised the barbarism of the Nazi Regime, it is argued by Ian Kershaw, that he wanted to see the Reich dominating central and eastern Europe. (10)

Although he remained in the government he did make contact with the German Resistance. This included Helmuth von Moltke, Peter von Wartenburg, Hans Oster and Carl Goerdeler. He also helped his old boss, Rudolf Hilferding, to escape from Nazi Germany. (11) Over a period of time he secretly traveled the road from opposition to resistance to conspiracy. A monarchist, he attempted unsuccessfully to persuade his fellow conspirators to support the Hohenzollern Crown Prince as successor to Hitler. (12)

Operation Valkyrie

In January, 1942, a group of men that included Johannes Popitz, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, General Friedrich Olbricht, Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, Colonel Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim, General-Major Henning von Tresckow, General-Major Hans Oster, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Dohnanyi, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Carl Langbehn, Helmuth von Moltke, Peter von Wartenburg and Jakob Kaiser, decided to overthrow Adolf Hitler. The conspiracy was called Operation Valkyrie. (13)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich von Hassell, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg,Eugen Gerstenmaier, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (14)

Moltke and Goerdeler clashed over several different issues. According to Theodore S. Hamerow: "Goerdeler was the opposite of Moltke in temperament and outlook. Moltke, preoccupied with the moral dilemmas of power, could not deal with the practical problems of seizing and exercising it. He was overwhelmed by his own intellectuality. Goerdeler, by contrast, seemed to believe that most spiritual quandaries could be resolved through administrative expertise and managerial skill. He suffered from too much practicality. He objected to the policies more than the principles of National Socialism, to the methods more than the goals. He agreed in general that the Jews were an alien element in German national life, an element that should be isolated and removed. But there is no need for brutality or persecution. Would it not be better to try and solve the Jewish question by moderate, reasonable means?" (15)

Some historians have defended Goerdeler from claims that he was an ultra-conservative: "Goerdeler has frequently been accused of being a reactionary. To some extent this results from the vehemence with which differing points of view were often argued between the various political tendencies in the opposition. In Goerdeler's case the accusation is unjustified. Admittedly he, like Popitz, wished to avoid the pitfalls of mass democracy; he was concerned to form an elite... and some stable form of authority. This he wished to achieve, however, through liberalism and decentralization; his stable authority should be so constructed that it guaranteed rather than suppressed freedom." (16)

The conspirators eventually agreed who would be members of the government. Head of State: Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chancellor: Carl Goerdeler; Vice Chancellor: Wilhelm Leuschner; State Secretary: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg; State Secretary: Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin; Foreign Minister: Ulrich von Hassell; Minister of the Interior: Julius Leber; State Secretary: Lieutenant Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg; Chief of Police: General-Major Henning von Tresckow; Minister of Finance: Johannes Popitz; President of Reich Court: General-Major Hans Oster; Minister of War: Erich Hoepner; State Secretary of War: General Friedrich Olbricht; Minister of Propaganda: Carlo Mierendorff; Commander in Chief of Wehrmacht: Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben; Minister of Justice: Josef Wirmer. (17)

Carl Langbehn and Heinrich Himmler

Popitz believed that he could exploit the differences inside the Nazi leadership and bring about a split by persuading Heinrich Himmler to lead a coup against Hitler. In August 1943, Popitz had a meeting with two senior figures in the resistance: General Friedrich Olbricht and General-Major Henning von Tresckow. They gave their approval to the strategy. So also did Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, who "believed a putsch carried out by generals was bound to fail" and he was only willing to participate "on the condition" that the putsch had the support of Himmler." (18)

Carl Langbehn, Himmler's lawyer, was also a member of the resistance. He approached Himmler and managed to persuade him to meet Popitz. On 26th August, Popitz had an interview with Himmler in the Reich Ministry of the Interior. "Apparently Popitz began by flattering Himmler's vanity as the guardian of National Socialist values under attack by Party corruption and misdirection of the war effort. The war was no longer winnable, he went on, and if they carried it on as formerly they were heading for defeat or stalemate at best." (19)

According to Peter Hoffmann: "Adroitly he suggested that Himmler assume the role of guardian of the true Holy Grail of Nazism; someone was required to re-establish order, both at home and abroad, after all the corruption and the unhappy conduct of the war by a single overloaded man. The war could no longer be won, he said, but it would only be lost if it continued to be conducted on these lines." Popitz pointed out that because of their fear of communism, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were still willing to negotiate, but not with Hitler or Joachim von Ribbentrop. (20)

Popitz and Himmler agreed to further talks but these never took place because in September 1943 Langbehn was arrested by the Gestapo. It seems that they had intercepted an Allied message that had been sent to Langbehn. It was shown to Himmler and he had to choice but to act, though he contrived to avoid ordering a trial. Popitz retained his freedom but now his fellow conspirators tended to keep their distance as it was feared that he was being closely observed by the authorities. (21) It seems that Hitler was also highly suspicious of Popitz. Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Hitler is absolutely convinced that Popitz is our enemy. He is already having him watched so as to have incriminating material about him ready; the moment Popitz gives himself away, he will close in on him." (22)

Ulrich von Hassell was very worried by these developments. He received news that two senior figures in the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller and Walter Schellenberg, were involved in the interrogation. Hassell was worried that if Langbehn was tortured he might mention that he was a member of the German Resistance. He was afraid for his wife and children as Langbehn's wife and secretary were also arrested. "The Gestapo have locked up Langbehn, his wife, secretary and Puppi Sarre (a close friend)... Now Langbehn will disappear from circulation, the man who helped so many victims of the Gestapo, quite apart from the political consequences." (23)

July Plot

In October 1943, Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, joined Operation Valkyrie. While serving in Africa, Stauffenberg was wounded in the face, in both hands, and in the knee by fire from a low-flying Allied plane. According to one source: "He feared that he might lose his eyesight completely, but he kept one eye and lost his right hand, half the left hand, and part of his leg." After he recovered it was decided that it would be impossible to serve on the front line and in October, 1943, he was appointed as Chief of Staff in the General Army Office. (24)

The group was pleased by the arrival of Stauffenberg who brought new dynamism to the attempt to remove Hitler. Stauffenberg volunteered to be the man who would assassinate Hitler: "With the help of men on whom he could rely at the Führer's headquarters, in Berlin and in the German Army in the west, Stauffenberg hoped to push the reluctant Army leaders into action once Hitler had been killed. To make sure that this essential preliminary should not be lacking, Stauffenberg allotted the task of assassination to himself despite the handicap of his injuries. Stauffenberg's energy had put new life into the conspiracy, but the leading role he was playing also roused jealousies." (25)

Claus von Stauffenberg now decided to carry out the assassination himself. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Johannes Popitz and Carl Goerdeler and wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany. (26)

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism." (27)

On 20th July, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and Werner von Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived." (28)

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (29)

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (30)

General Friedrich Fromm arrested Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General Friedrich Olbricht, Colonel Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim and Lieutenant Werner von Haeften. Fromm decided that he would hold an immediate court-martial. Stauffenberg spoke out, claiming in a few clipped sentences sole responsibility for everything and stating that the others had acted purely as soldiers and his subordinates. (31)

All the conspirators were found guilty and sentenced to death. Hoepner, an old friend, was spared to stand further trial. Beck requested the right to commit suicide. According to the testimony of Hoepner, Beck was given back his own pistol and he shot himself in the temple, but only managed to give himself a slight head wound. "In a state of extreme stress, Beck asked for another gun, and an attendant staff officer offered him a Mauser. But the second shot also failed to kill him, and a sergeant then gave Beck the coup de grâce. He was given Beck's leather overcoat as a reward." (32)

The condemned men were taken to the courtyard. Drivers of vehicles parked in the courtyard were instructed to position them so that their headlight would illuminate the scene. General Olbricht was shot first and then it was Stauffenberg's turn. He shouted "Long live holy Germany." The salvo rang out but Haeften had thrown himself in front of Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg. Quirnheim was the last man shot. It was 12.30 a.m. (33)

Arrest and Execution

Heinrich Himmler gave order for the arrest of Popitz the day after the failure of the July Plot. Other members of the group were also taken into custody. This included Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, General-Major Hans Oster, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, Helmuth von Moltke, Peter von Wartenburg, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ulrich Hassell and Hjalmar Schacht. Others such as General-Major Henning von Tresckow committed suicide rather than be arrested and tortured. (34)

Popitz told the Gestapo: "The Jewish question had to be dealt with, their removal from state and economy was unavoidable. But the use of force which led to the destruction of property, to arbitrary arrests and to the destruction of life could not be reconciled with law and morality, and, in addition, seemed to me to have dangerous implications for people's attitudes to property and human life. At the same time, I saw in the treatment of the Jewish Question a great danger of increasing international hostility to Germany and its regime".(35)

Popitz was condemned to death by Roland Freisler before the People's Court on 3rd October, 1944. His execution was delayed for four months, primarily through the intercession of Himmler, who thought that Popitz might be useful to him as a possible intermediary with the Western Allies through Sweden and Switzerland. However, as it became clear that the Allies were unwilling to negotiate, it was decided to have him executed. (36)

Johannes Popitz was hanged on 2nd February 1945 at Plötzensee Prison, in Berlin.

Primary Sources

(1) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003)

The group around Popitz and Hassell had no doubt about the mission of the old upper class, from which this group came; and even Goerdeler, who thought on less aristocratic lines, joined in Hassell's repeated complaints that Nazi propaganda pursued the nobility and the upper class with downright hatred. In 1934 Popitz gave an address to the Wednesday Club, in which he expressed the view that it was necessary to establish a governing class.

(2) Roger Manvell & Heinrich Fraenkel, Heinrich Himmler (1965)

Popitz is another curious figure whose actual position it is difficult to determine; he was not a member of the Nazi Party but remained from 1933 until his arrest in 1944 Prussian Minister of State and Finance under Goring. He had been a friend of Schleicher, and it was probably at the time of Schleicher's murder by the Nazis in 1934 that he began to entertain the doubts that eventually made him one of the more ardent members of the resistance. The fact that he had once been a supporter of the Nazis and as late as 1937 accepted the golden badge of the Party from Hitler made him suspect in the eyes of members of the resistance. Also he was politically very right-wing and favoured a return of the monarchy.

(3) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (September, 1943)

Hitler is absolutely convinced that Popitz is our enemy. He is already having him watched so as to have incriminating material about him ready; the moment Popitz gives himself away, he will close in on him.

(4) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977)

On 26 August Popitz had an interview with Himmler in the Reich Ministry of the Interior, which Himmler had just taken over. Adroitly he suggested that Himmler assume the role of guardian of the true Holy Grail of Nazism; someone was required to re-establish order, both at home and abroad, after all the corruption and the unhappy conduct of the war by a single overloaded man. The war could no longer be won, he said, but it would only be lost if it continued to be conducted on these lines. In view of the bolshevist menace Great Britain and the United States were still ready to negotiate, but not with Ribbentrop...

In September 1943 Langbehn was arrested by the Gestapo. Some Allied message (Dulles insists that it was neither British nor American) was deciphered by the Germans and gave away Langbehn's Swiss contacts. It was shown to Himmler and he had to choice but to act, though he contrived to avoid ordering a trial.

(5) Peter Padfield, Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991)

Apparently Popitz began by flattering Himmler's vanity as the guardian of National Socialist values under attack by Party corruption and misdirection of the war effort. The war was no longer winnable, he went on, and if they carried it on as formerly they were heading for defeat or stalemate at best. On the other hand Great Britain and the United States recognised the danger of Bolshevism and were ready to negotiate – but not with von Ribbentrop… Himmler, while remaining as always noncommittal, scrutinising him from behind his pince-nez, showed no sign of disapproving the general trend of the argument, and the following day Wolff arranged with Langbehn for Popitz to see Himmler again to take the discussion further. Langbehn immediately travelled to Switzerland to inform his western contacts of this encouraging news.

(6) Johannes Popitz, interviewed by the Gestapo (July, 1944)

As somebody who was very familiar with conditions in the Weimar Republic, my view of the Jewish question was that the Jews ought to disappear from the life of the state and the economy. However, as far as the methods were concerned, I repeatedly advocated a somewhat more gradual approach, particularly in light of diplomatic considerations…. The Jewish question had to be dealt with, their removal from state and economy was unavoidable. But the use of force which led to the destruction of property, to arbitrary arrests and to the destruction of life could not be reconciled with law and morality, and, in addition, seemed to me to have dangerous implications for people's attitudes to property and human life. At the same time, I saw in the treatment of the Jewish Question a great danger of increasing international hostility to Germany and its regime".