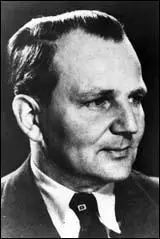

Carlo Mierendorff

Carlo Mierendorff was born in Grossenhain, Germany on 24th March, 1897. His father, Georg Mierendorff, worked in the textile industry. He attended the Ludwig-Georgs-Gymnasium in Darmstadt.

On the outbreak of the First World War In 1914, Mierendorff volunteered for the Germany Army. Mierendorff received the Iron Cross II class during the Battle of Łódź. He suffered from illness over the next year but returned to the Western Front and in 1917 he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class. (1)

After the war he studied economics in Heidelberg University. He was active in the Socialist Student Group and the Association of Republican Students while at university and in 1920 he joined the German Social Democratic Party. (2) The writer, Gerhart Hauptmann, who got to know him as a young man, described him as a "born leader". (3)

In 1922 he came into conflict with the anti-Semitic head of the Heidelberg Physical Institute, the Nobel Prize winner Philipp Lenard, because he failed to show sympathy towards the murder of Walther Rathenau. Mierendorff pointed out that Lenard was a supporter of the Nazi Party. During the protests he was arrested and charged with a breach of the peace. (4)

After leaving university Mierendorff worked for the German Transport Workers' Association in Berlin. Then he was a feature editor at the Hessisches Volksfreund in Darmstadt. From 1926 to 1928 he was secretary of the SPD parliamentary group in the Reichstag and became press officer for interior minister Wilhelm Leuschner. (5)

Carlo Mierendorff: Anti-Nazi Politician

In the September 1930 Reichstag election, Mierendorff won a seat and became the youngest member of his party in parliament. He led the fight against the growth in the Nazi Party and published Face and Character of the National Socialist Movement. It has been claimed by Hans Mommsen that in the early 1930s Mierendorff had turned "against a system of democratic formalities, which opens the door wide to the political interests of powerful pressure-groups, and thus provides neither strong government nor genuine self-government and co-determination by the people." (6)

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). Carlo Mierendorff refused to go: "We can't just all go to the Riviera." (7)

However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (8)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. This included Carlo Mierendorff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Theodor Haubach and Julius Leber. (9) Mierendorff later recalled that he was delivered by camp authorities into the hands of Communist fellow prisoners, who beat him nearly to death. (10)

By the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp. Mierendorff, Leber and Leuschner were all released from concentration camps in 1937-1938. (11)

The overwhelming majority of social-democratic resistance groups had failed to survive the first half of the 1930s. (12) Mierendorff, Leber and Leuschner were all released from concentration camps in 1937-1938. Joachim Fest argues that this reflected the self-confidence of the Hitler government. "The sharp decline in unemployment, the improving economy, and the social programs of the new regime had produced a sense of general well-being, even pride, among the working-class... The enormous self-confidence of the Nazis in their handling of labour is suggested in the release from concentration camps in 1937 and 1938 of three once popular labour leaders - Julius Leber, Carlo Mierendorff, and last acting chairman of the General German Trade Union Federation, Wilhelm Leuschner." (13)

The Kreisau Circle

In 1940 Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke joined forces to establish the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who were ideologically opposed to fascism. Carlo Mierendorff joined this group. Other people involved included Adam von Trott, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Freya von Moltke, Theodor Haubach, Marion Yorck von Wartenburg, Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin, Dietrich Bonhoffer, Harald Poelchau and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (14)

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." (15) Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic." (16)

Members of the group came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the outlawed Social Democratic Party and the Church. "There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler." (17)

Several members were Christian Socialists who believed the religious establishment had failed Germany. Alfred Delp was highly critical of the hierarchical bureaucracy of the Catholic Church, which he said had lost sight of human beings as the subject and object of ecclesiastical life. He agreed with Adam von Trott who wrote about the Kreisau Circle: "The key to their joint efforts is the desperate attempt to rescue the core of personal human integrity. Their fundamental ambition is to restore the inalienable divine and natural right of the human individual." This was something that Delp called "God-guided humanism". (18)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Theodor Haubach, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (19)

Moltke and Goerdeler clashed over several different issues. According to Theodore S. Hamerow: "Goerdeler was the opposite of Moltke in temperament and outlook. Moltke, preoccupied with the moral dilemmas of power, could not deal with the practical problems of seizing and exercising it. He was overwhelmed by his own intellectuality. Goerdeler, by contrast, seemed to believe that most spiritual quandaries could be resolved through administrative expertise and managerial skill. He suffered from too much practicality. He objected to the policies more than the principles of National Socialism, to the methods more than the goals. He agreed in general that the Jews were an alien element in German national life, an element that should be isolated and removed. But there is no need for brutality or persecution. Would it not be better to try and solve the Jewish question by moderate, reasonable means?" (20)

Moltke expressed the expectation that "a great economic community would emerge from the demobilization of armed forces in Europe" and that it would be "managed by an internal European economic bureaucracy". Combined with this he hoped to see Europe divided up into self-governing territories of comparable size, which would break away from the principle of the nation-state. Although their domestic constitutions would be quite different from each other, he hoped that by the encouragement of "small communities" they would assume public duties. His idea was of a European community built up from below. (21) Mierendorff supported Moltke and insisted on "factory unions rather than trade unions". (22)

Moltke made great efforts to involve representatives of the working class in the work of the Kreisau Circle. He therefore reached out to Carlo Mierendorff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Theodor Haubach, Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein who had all been members of the Social Democratic Party before it was banned by Adolf Hitler. Mierendorff, as a Christian Socialist, was closer to Moltke's philosophy, which saw the "revival of Christian convictions as a means of defeating the mass mentality". (23)

The conspirators eventually agreed who would be members of the government after the overthrow of Hitler. Carlo Mierendorff was to become the Minister of Propaganda. Other positions included: Head of State: Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chancellor: Carl Goerdeler; Vice Chancellor: Wilhelm Leuschner; State Secretary: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg; Foreign Minister: Ulrich Hassell; Minister of the Interior: Julius Leber; State Secretary: Lieutenant Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg; Chief of Police: General-Major Henning von Tresckow; Minister of Finance: Johannes Popitz; President of Reich Court: General-Major Hans Oster; Minister of War: Erich Hoepner; State Secretary of War: General Friedrich Olbricht; Commander in Chief of Wehrmacht: Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben; Minister of Justice: Josef Wirmer. (24)

Principles of the New Order

In 1943 Carlo Mierendorff contributed to the Kreisau Circle's document, Principles of the New Order. This included a section on the role of the trades union movement in Germany after the war. Mierendorff insisted that the working-class would be important in implementing the economic programme which was essential to the rebuilding of the state: "The German Labour Union will fulfil its purpose by putting through this programme and by transferring its appointed tasks to the organs of the state and to self-governing industry and commerce." (25)

Mierendorff argued for the need for the "socialist regulation of the economy" designed to realize "human dignity and political freedom," and to ensure a "secure existence for the clerical employees and workers in industry and agriculture and for the peasant on his land." This was an essential precondition for "social justice and freedom." In addition, the "expropriation of key enterprises in heavy industry" would end the "pernicious abuse of the political power of big business." The economy as a whole should be reorganized on the principle of self-administration with "equal participation for the working population as the fundamental element in a socialist order." Finally, the general welfare of the nation required a "reduction in bureaucratic centralism" and an "organic reconstruction of the Reich based on the member states." (26)

Mierendorff published a document under the heading Mierendorff's Call to Arms. Mierendorff, who was being followed by the Gestapo, was unable to appear at the Kreisau Circle meeting on 14th June, 1943 for security reasons. (27) It was presented on his behalf by fellow socialist, Eugen Gerstenmaier. As a result of the paper it was decided to establish a "Socialist Action" committee. However, Mierendorff's idea of working with the underground German Communist Party (KPD) was rejected. Mierendorff and other socialists such as Julius Leber, Theodor Haubach, Wilhelm Leuschner and Adolf Reichwein, now fully supported the plan devised by Claus von Stauffenberg to assassinate Hitler. (28)

On 4th December, 1943, Carlo Mierendorff was killed in an air raid on Leipzig by the Royal Air Force . According to witnesses, his final word, shouted from the burning cellar, was "Madness". (29) Hans Gisevius pointed out that this was a terrible blow to both the German Resistance and the Kreisau Circle as "with him was lost the strongest and most ardent personality among the Social Democrats." (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler (1997)

Carlo Mierendorff joined the socialist movement as a young literature student. He became one of the most colourful and passionate figures in the German resistance - a "born leader," in the words of one contemporary. Arrested in 1933, shortly after Hitler seized power, Mierendorff spent a total of five years in concentration camps, which he later called "the silent world".

(2) Theodore S. Hamerow, On the Road to the Wolf's Lair - German Resistance to Hitler (1997)

The proclamation expressing the views of the Kreisau Circle, which the Hessian Socialist Carlo Mierendorff drafted in the summer of 1943... It referred to a "socialist regulation of the economy" designed to realize "human dignity and political freedom," and to ensure a "secure existence for the clerical employees and workers in industry and agriculture and for the peasant on his land." This was an essential precondition for "social justice and freedom." In addition, the "expropriation of key enterprises in heavy industry" would end the "pernicious abuse of the political power of big business." The economy as a whole should be reorganized on the principle of self-administration with "equal participation for the working population as the fundamental element in a socialist order." Finally, the general welfare of the nation required a "reduction in bureaucratic centralism" and an "organic reconstruction of the Reich based on the member states."