The Kreisau Circle

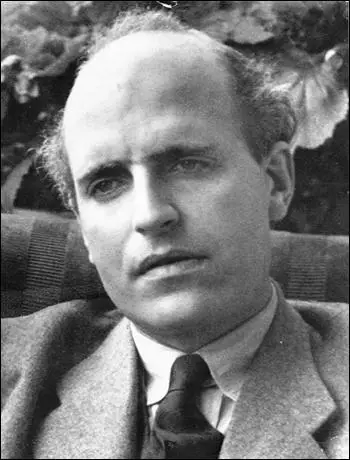

Helmuth von Moltke, grew up with a preference for Christian, democratic, and international institutions. At the age of 14 he became confirmed in the Evangelical Church of Prussia. He later wrote: "I have struggled all my life - beginning in my school days - against the narrow-mindedness and arrogance, the penchant for violence, the merciless consistency and the love of the absolute, that seems to be inherent in the Germans... I have also done what I could do to ensure that this spirit - with its excessive nationalism, persecution of other races, agnosticism, and materialism - is defeated." (1)

Moltke studied law and political sciences in Breslau, Vienna, Heidelberg, and Berlin between 1927 to 1929. The following year, at the age of twenty-three, Von Moltke he took over the management of the family estate at Kreisau. including the Marxist playwright, Bertolt Brecht. (2) Moltke became involved in a scheme where unemployed young workers and young farmers were brought together with students so that they could learn from one another. In 1931, he married Freya Deichmann, also a lawyer and someone who shared his progressive political opinions. Moltke was an early opponent of Adolf Hitler and detested his racial theories and was "free from the anti-Semitic prejudice so common among his class." (3)

In 1935, Helmuth von Moltke declined the chance to become a judge to avoid having to join the Nazi Party. Instead, he opened a law practice in Berlin. As a lawyer dealing in international law, he helped victims of Hitler's régime emigrate. (4) During this period he spent time in London where he made important contacts with the British government. Other lawyers involved in advising Neville Chamberlain on how to deal with Hitler included Adam von Trott and Fabian Schlabrendorff. These lawyers suggested to Chamberlain to make it clear that he was willing to go to war in order to halt Hitler's aggression. However, it did not "lead to any readiness on the part of the British government to cooperate with the German resistance movement." (5)

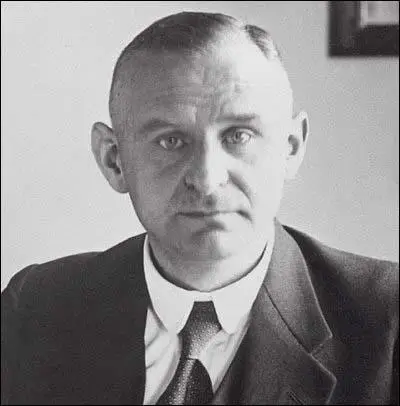

Von Moltke became friendly with Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, who was also opposed to the policies of Hitler's government. In 1936 Wartenburg was appointed as assistant secretary to the Reich Price Commission in Berlin. He refused to join the Nazi Party and therefore never received any further promotions. (6) The opposition of both men to fascism increased after Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938). (7)

Another opponent of Hitler was Adam von Trott, the fifth child of the Prussian Culture Minister August von Trott zu Solz. He obtained his Abitur degree in 1927 and went on to study law at the universities of Munich and Göttingen. In 1931 he went to Mansfield College at Oxford University. In 1937 he was employed by the American Institute of Pacific Relations on a project in China. In October 1938 Von Trott went to Washington to inform his friends there of the German Resistance. (8)

Trott believed that Neville Chamberlain should make it clear to Adolf Hitler that the appeasement policy was going to end. On 1st June, 1939, he arrived in London to have talks with British officials, including Edward Wood (Lord Halifax) and Philip Henry Kerr (Lord Lothian). According to Peter Hoffmann: At this time Trott was wondering whether he should leave Germany for the duration of the Nazi regime which he loathed, or whether he could fight the regime in some way." (9)

Wartenburg and Moltke were free from the anti-Semitic prejudice so common among their class. Unlike many members of the resistance, nationalistic motives were only of secondary importance. "Both men made their judgments from a Christian and universalist viewpoint, and regarded the defeat of Nazism not primarily as a German problem, but one which genuinely concerned the whole western world. Neither of them faced the problem of having to separate a supposedly beneficial policy of segregation from criminally violent treatment of the Jews. For them, Jewish persecution had become symptomatic of the long decline of the west." (10)

Outbreak of the Second World War

Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg was called up as a reserve officer on the outbreak of the Second World War, He took part in the invasion of Poland before being assigned to the Armed Forces High Command in Berlin in 1942. While at Abwehr he joined Wilhelm Canaris, Hans Dohnanyi, Hans Oster and Hans Gisevius in the conspiracy against Adolf Hitler. Gisevius was later to comment that "Wilhelm Canaris's (chief of Abwehr) great achievement" was to promote Major-General Oster into a position where he could organize "an intelligence service of his own within the counter-intelligence service." (11)

Helmuth von Moltke also joined Abwehr, the High Command of the Armed Forces, Counter-Intelligence Service, Foreign Division, under Admiral Canaris, as an expert in martial law and international public law. Moltke's work for the Abwehr mainly involved gathering insights from abroad, from military attachés and foreign newspapers, and news of military-political importance, and relaying this information to the Wehrmacht. Over the next few years he wrote regularly, almost daily, to his wife Freya von Moltke. "The correspondence, saved by a miracle from the Gestapo, now forms one of the most delightful and interesting records of that time." (12)

Moltke's work for the Abwehr mainly involved gathering insights from abroad, from military attachés and foreign newspapers, and news of military-political importance, and relaying this information to the Wehrmacht. Unlike most of his colleagues he did not celebrate the successes of the German Army. On 17th June, 1940, three days after the fall of Paris, while everyone around him was rejoicing at the extraordinary victory of German arms, Moltke spoke in a letter to a friend about the "triumph of evil". Moltke admitted that he would have to wade through a "swamp of outward success, ease, and well-being" and suggested that defeat on the battlefield would have been preferable to "this progressive corruption of the national soul". (13)

Formation of the Kreisau Circle

In 1940 Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke joined forces to establish the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who were ideologically opposed to fascism. Other people who joined included Adam von Trott, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Carlo Mierendorff, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Freya von Moltke, Theodor Haubach, Marion Yorck von Wartenburg, Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin, Dietrich Bonhoffer, Harald Poelchau and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (14)

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." (15) Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic." (16)

Members of the group came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the outlawed Social Democratic Party and the Church. "There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler." (17)

The group disagreed about several different issues. Whereas Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke were strongly anti-racist, others such as Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, believed that Jews should be eliminated from public service and evinced unmistakably anti-Semitic prejudice. "As late as 1938 he repeated his call for the removal of Jews from government and the civil service. His biographer, Albert Krebs, attests that he 'was never able to rid himself of feelings of alienation toward the intellectual and material world of Jewry.' He was appalled to learn of the crimes perpetrated against the Jewish population in the occupied Soviet Union, but this was not a major factor in his determination to see Hitler removed." (18)

Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) has argued that one of strengths of the Kreisau Circle was that it had no established leader: "It consisted of of highly independent personalities holding views of their own. They were both able and willing to compromise, for they knew that politics without compromise was impossible. In the discussion phase, however, they clung to their own views." (19) Although the Kreisau Circle did not have a leader, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke were the two most important figures in the group. Joachim Fest, the author of Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) has pointed out the Moltke has been described as the "engine" of the group, Wartenburg was its "heart". (20)

Several members were Christian Socialists who believed the religious establishment had failed Germany. Alfred Delp was highly critical of the hierarchical bureaucracy of the Catholic Church, which he said had lost sight of human beings as the subject and object of ecclesiastical life. He agreed with Adam von Trott who wrote about the Kreisau Circle: "The key to their joint efforts is the desperate attempt to rescue the core of personal human integrity. Their fundamental ambition is to restore the inalienable divine and natural right of the human individual." This was something that Delp called "God-guided humanism". (21)

Delp remained active in the Kreisau Circle and Joachim Fest argues that what brought the men together was not principally a determination to overthrow the Nazi regime, but more a discussion about what a post-Hitler Germany would look like: "There was a strong utopian streak in their thought and planning, which was infused with Christian and socialist ideals, as well as remnants from the youth movement of a romantic belief in the dawning of a new era. They basically believed that all social and political systems were reaching a dead end and that capitalism and Communism, no less than Nazism, were symptomatic of the crisis deep and all encompassing in modern mass society." (22)

Adam von Trott became a very important member of the group. During the first winter of the war he began to think about the long-time future of Europe. He suggested that a European tariff and currency union, the setting up of a European Supreme Court and single European citizenship, as the basis for a future administrative unification of Europe. Moltke agreed and called for the setting up of a "supreme European legislature", which would be answerable, not to the national self-governing bodies, but to the individual citizens, by whom it would be elected. In other words, an European Parliament. (23)

Helmuth von Moltke agreed with Trott and expressed the expectation that "a great economic community would emerge from the demobilization of armed forces in Europe" and that it would be "managed by an internal European economic bureaucracy". Combined with this he hoped to see Europe divided up into self-governing territories of comparable size, which would break away from the principle of the nation-state. Although their domestic constitutions would be quite different from each other, he hoped that by the encouragement of "small communities" they would assume public duties. His idea was of a European community built up from below. (24)

In June, 1940, Helmuth von Moltke wrote to his wife, Freya von Moltke: "It is our duty to recognize what is repugnant, to analyse it, to defeat it through a superior synthesis and thus make it serve our purpose." At the same time his thoughts were revolving around the question of whether he would be lucky enough to survive the stage "between intellectual triumph and actual revolution", and he comforted himself by pointing out that in retrospect the "time span between Voltaire's heralding of the French Revolution and its arrival had been short." (25)

Helmuth von Moltke had to travel through German-occupied Europe and observed many human rights abuses including the killing of civilians. In October 1941, Moltke wrote to his wife: "In one area in Serbia two villages have been reduced to ashes.... In Greece 220 men of one village have been shot.... In France there are extensive shootings while I write. Certainly more than a thousand people are murdered in this way every day and another thousand German men are habituated to murder... Since Saturday the Berlin Jews are being rounded up. Then they are sent off with what they can carry.... May I know this and yet sit at my table in my heated flat and have tea? What shall I say when I am asked: And what did you do during that time.... How can anyone know these things and still walk around free?" (26)

The atrocities increased after the invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) on 22nd June, 1941. Moltke wrote a now-famous memo opposing the Nazi policy to ignore the Geneva and The Hague Conventions for Soviet prisoners, since Moscow was not a signatory. Von Moltke argued it was important to create a "tradition of compliance" with international law, and that good treatment of Soviet prisoners would offer ground for good treatment of German prisoners. The memo created a stir in the High Command of the German Army and it was required Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel to finally dismiss it, saying the Geneva Convention was "a product of a notion of chivalry of a bygone era." (27)

Helmuth von Moltke became aware that terrible things we taking place under the rule of Hitler. He encountered a nurse on the tram and she was very drunk. Moltke helped her off at her stop. She said to him, "I expect it horrifies you to see me like this." He replied, "No, not horrified; but I'm sorry to see someone like you in such a state." She told him, "I work in an SS hospital, and there the sick, the men who cannot shut out what they have done and seen, cry out all the time, 'I can't do it any more! I can't do it any more!' If you have to listen to that all day, you reach for the bottle at night." (28)

Negotiations with the Allies

Helmuth von Moltke also made several attempts to negotiate with the British government. In May 1942 he arranged for Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a member of the Kreisau Circle, and Hans Schönfeld, a fellow clergyman, to meet Bishop George Bell in Stockholm. Bonhoeffer and Schönfeld asked Bell: "Would the Allies adopt a different stance toward a Germany that had liberated itself from Hitler than they would toward a Germany still under his rule? Bell reported back to the British Foreign Office, but Anthony Eden wrote back only to say he was "satisfied that it is not in the national interest to provide an answer of any kind." A few months later, Bell approached the British Foreign Office again, Eden noted in the margin of his reply, "I see no reason whatsoever to encourage this pestilent priest!" (29)

The following year Helmuth von Moltke went to Stockholm with the latest leaflets being distributed by the White Rose resistance group. Eugen Gerstenmaier and Adam von Trott also went to the city to try and negotiate with representatives of the British government. Trott told them: "We cannot afford to wait any longer. We are so weak that we will only achieve our goal if everything goes our way and we get outside help." However, they received no encouragement. "The Allies did not even trouble themselves to reject the various attempts to contact them; they simply closed their eyes to the German resistance, acting as if it did not exist." (30)

Carl Goedeler and the Kreisau Circle

The most active of those in the German resistance seeking a negotiated peace agreement with the Allies was Carl Goerdeler. The former lord mayor of Leipzig, and an early supporter of the Nazi Party, he accepted the post as Reich Commissioner of Prices. He attempted without success to win Hitler's support for major reforms in local administration. In November 1936, while Goerdeler was abroad, the Nazi councillors of Leipzig removed the statue of the statue of the composer Felix Mendelssohn from its position opposite the Gewandhaus concert hall. On his return Goerdeler resigned in protest as mayor of the city. (31) He became financial adviser to the Stuttgart firm of Robert Bosch. This involved travelling abroad and before the outbreak of war he visited London and urged the British government to be tough and flexible in dealing with the Third Reich. (32)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (33)

Moltke and Goerdeler clashed over several different issues. According to Theodore S. Hamerow: "Goerdeler was the opposite of Moltke in temperament and outlook. Moltke, preoccupied with the moral dilemmas of power, could not deal with the practical problems of seizing and exercising it. He was overwhelmed by his own intellectuality. Goerdeler, by contrast, seemed to believe that most spiritual quandaries could be resolved through administrative expertise and managerial skill. He suffered from too much practicality. He objected to the policies more than the principles of National Socialism, to the methods more than the goals. He agreed in general that the Jews were an alien element in German national life, an element that should be isolated and removed. But there is no need for brutality or persecution. Would it not be better to try and solve the Jewish question by moderate, reasonable means?" (34)

Moltke and Wartenburg were free from the anti-Semitic prejudice. Unlike many members of the resistance, nationalistic motives were only of secondary importance. "Both men made their judgments from a Christian and universalist viewpoint, and regarded the defeat of Nazism not primarily as a German problem, but one which genuinely concerned the whole western world. Neither of them faced the problem of having to separate a supposedly beneficial policy of segregation from criminally violent treatment of the Jews. For them, Jewish persecution had become symptomatic of the long decline of the west." (35)

Some historians have defended Goerdeler from claims that he was an ultra-conservative: "Goerdeler has frequently been accused of being a reactionary. To some extent this results from the vehemence with which differing points of view were often argued between the various political tendencies in the opposition. In Goerdeler's case the accusation is unjustified. Admittedly he, like Popitz, wished to avoid the pitfalls of mass democracy; he was concerned to form an elite... and some stable form of authority. This he wished to achieve, however, through liberalism and decentralization; his stable authority should be so constructed that it guaranteed rather than suppressed freedom." (36)

When Goerdeler worked for Adolf Hitler as Reich Commissioner of Prices he argued against the persecution of Jews in order to develop a better relationship with the Allied powers: "I can well imagine that we will have to bring certain issues... into a greater degree of alignment with the imponderable attitudes of other peoples, not in substance, but in the manner of dealing with them". (37)

Goerdeler then went on to argue that "a new arrangement regarding the position of the Jews seems necessary throughout the world." Something had to be done. "That the Jewish people belong to a different race is common knowledge." Goerdeler believed that: "The world will have peace only when the Jewish people are given a real opportunity to establish and maintain their own state... perhaps... in parts of Canada or South America." Those left in Germany would be classed as "resident aliens" who would be barred from the civil service and the franchise. He was against the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws, but disapproved of "racial mixture" through intermarriage could be left to "the sound common sense of the people". (38)

Carl Goerdeler and Colonel-General Ludwig Beck had written an article in 1941 entitled The Goal. It began with a long analysis of German history and German political development. It looked to Britain with admiration for the way it had developed and run its Empire. At the same time it looked forward to a federation of European nations under German leadership "within ten or twenty years". It included a reference to the innate superiority of "the white race". In another essay three years later it still blamed the French for being too harsh in the negotiations following the First World War. (39)

Moltke, as a socialist, disagreed with the Goerdeler group mover several different issues. However, he was determined to persuade all members of the German resistance to agree on a common programme. He "waged a continual battle to persuade his new-found partners to agree among themselves... to prevent them dropping out altogether". He spoke about a "fundamental danger-zone, where some people hope that by sacrificing principles they will make the boat more buoyant, forgetting that by doing so they make it impossible to steer." (40)

Over a period of time Goerdeler and his followers did move over certain issues. For example, at first Goerdeler had strong reservations about Kreisau Circle's radical plan for Europe, but by 1942 their positions became ever closer. In 1943, Goerdeler called for the dismantling of tariff barriers, "equality of economic rights" and "standardized transport arrangements". He also advocated the setting up of European ministries of economics and foreign affairs. Later he talked about the need for "a European federation of states". In one memorandum he wrote that the war "must lead to a close union of the nations of Europe, if the sacrifices are to have any purpose". (41)

Principles of the New Order

In 1943 Carlo Mierendorff contributed to the Kreisau Circle's document, Principles of the New Order. This included a section on the role of the trades union movement in Germany after the war. Mierendorff insisted that the working-class would be important in implementing the economic programme which was essential to the rebuilding of the state: "The German Labour Union will fulfil its purpose by putting through this programme and by transferring its appointed tasks to the organs of the state and to self-governing industry and commerce." (42)

Mierendorff argued for the need for the "socialist regulation of the economy" designed to realize "human dignity and political freedom," and to ensure a "secure existence for the clerical employees and workers in industry and agriculture and for the peasant on his land." This was an essential precondition for "social justice and freedom." In addition, the "expropriation of key enterprises in heavy industry" would end the "pernicious abuse of the political power of big business." The economy as a whole should be reorganized on the principle of self-administration with "equal participation for the working population as the fundamental element in a socialist order." Finally, the general welfare of the nation required a "reduction in bureaucratic centralism" and an "organic reconstruction of the Reich based on the member states." (43)

Mierendorff published a document under the heading Mierendorff's Call to Arms. Mierendorff, who was being followed by the Gestapo, was unable to appear at the Kreisau Circle meeting on 14th June, 1943 for security reasons. (44) It was presented on his behalf by fellow socialist, Eugen Gerstenmaier. As a result of the paper it was decided to establish a "Socialist Action" committee. However, Mierendorff's idea of working with the underground German Communist Party (KPD) was rejected. Mierendorff and other socialists such as Julius Leber, Theodor Haubach, Wilhelm Leuschner and Adolf Reichwein, now fully supported the plan devised by Claus von Stauffenberg to assassinate Hitler. (45)

On 4th December, 1943, Carlo Mierendorff was killed in an air raid on Leipzig by the Royal Air Force . According to witnesses, his final word, shouted from the burning cellar, was "Madness". (46) Hans Gisevius pointed out that this was a terrible blow to both the German Resistance and the Kreisau Circle as "with him was lost the strongest and most ardent personality among the Social Democrats." (47)

The July Plot to kill Adolf Hitler

Claus von Stauffenberg decided to carry out the assassination of Adolf Hitler. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany. (48)

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism." (49)

The conspirators eventually agreed who would be members of the government. Head of State: Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chancellor: Carl Goerdeler; Vice Chancellor: Wilhelm Leuschner; State Secretary: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg; State Secretary: Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin; Foreign Minister: Ulrich Hassell; Minister of the Interior: Julius Leber; State Secretary: Lieutenant Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg; Chief of Police: General-Major Henning von Tresckow; Minister of Finance: Johannes Popitz; President of Reich Court: General-Major Hans Oster; Minister of War: Erich Hoepner; State Secretary of War: General Friedrich Olbricht; Minister of Propaganda: Carlo Mierendorff; Commander in Chief of Wehrmacht: Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben; Minister of Justice: Josef Wirmer. (50)

On 22nd July, 1944, Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein met with two members of the underground Central Committee of the German Communist Party (KPD). "The meeting place was the house of a Berlin doctor, Rudolf Schmid... It was agreed that no names would be given and no introductions made; one of the communists who knew Leber, however, exclaimed:'Oh you, Leber.' Two of the visitors were in fact communist party functionaries, Anton Saefkow and Franz Jacob." In fact, a third communist turned up to the meeting. He was Hermann Rambow, who was in fact a Gestapo agent. The following day, Leber, Reichwein, Saefkow and Jacob were arrested. (51)

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (52)

Stauffenberg went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (53)

Stauffenberg observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. He got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let the car go. (54)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (55)

However, General Erich Fellgiebel, Chief of Army Communications, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. (56) Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead." (57) As a result, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, Ludwig Beck, Eugen Gerstenmaier, and Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg arrived at army headquarters in order to become members of the new government. (58)

Trials and Executions

Adolf Hitler had survived the blast. He was seized by a "titanic fury and an unquenchable thirst for revenge" ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (59)

Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg was arrested along with Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and Friedrich Olbricht. His trial took place on 7th August, 1944. It resulted in the conviction of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, General Paul von Hase (the commandant of the Berlin garrison) and several junior officers. All the men were tried by Roland Freisler, the notorious Nazi judge. Witzleben was especially badly treated. The Gestapo had taken away his false teeth and belt. He was "unshaven, collarless and shabby." It was claimed that he had aged ten years in two weeks of Gestapo captivity. (60)

Adam von Trott was arrested and tortured. His trial took place in front of by Roland Freisler on 15th August, 1944. Joseph Goebbels ordered that every minute of the trial should be filmed so that the movie could be shown to the troops and the civilian public as an example of what happened to traitors. (61) He was found guilty but his execution of the death sentence was postponed in order to extract further information: "Since Trott has undoubtedly withheld a great deal, the death sentence pronounced by the People's Court has not been carried out so that Trott may be available for further clarification." Adam von Trott zu Solz was executed at Ploetzwnsee Prison on 25th August, 1944. (62)

Joseph Goebbels ordered that every minute of the trial should be filmed so that the movie could be shown to the troops and the civilian public as an example of what happened to traitors. (63) Wartenburg was particularly fearless and steadfast. He told the court: "The vital point running through all these questions is the totalitarian claim of the state over the citizen to the exclusion of his religious and moral obligation toward God." (64)

All the men were found guilty and sentenced to hang that afternoon. Hitler had ordered that they be hung like cattle. "I want to see them hanging like carcasses in a slaughterhouse!" he commanded. The entire event was filmed by the Reich Film Corporation. "Witzleben was first. Despite his poor showing at the trial, Witzleben met his death with courage and with as much dignity as was possible under the circumstances. A thin wire noose was placed around his neck, and the other end was secured to a meat hook. The executioner and his assistant then picked up the sixty-four-year-old soldier and dropped him so that his entire weight fell on his neck. They then pulled off his trousers so that he hung naked and twisted in agony as he slowly strangled. It took him almost five minutes to die, but he never once cried out. The other seven condemned men were executed in the same manner within an hour." (65)

Members of the Kreisau Circle was arrested and the following were executed over the next few months: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg (8th August, 1944), Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg (10th August, 1944), Adam von Trott (26th August, 1944), Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin (6th September, 1944), Wilhelm Leuschner (29th September, 1944), Adolf Reichwein (20th October, 1944), Julius Leber (5th January, 1945), Alfred Delp (2nd February, 1945) and Dietrich Bonhoffer (9th April, 1945).

Helmuth von Moltke was in prison at the time and was not involved in the July Plot, but he was charged with treason, especially for failing to report the early activities of his associates. He was condemned to death on 11th January, 1945 and in his last letter to his wife he wrote that he did not aim at martyrdom but regarded it as "an inestimable to die for something which... is worthwhile." He added that he was to be killed not for what he had done but what he had thought. Moltke was executed at Ploetzensee Prison on 23rd January, 1945. (40)

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997)

It was founded and held together by Helmuth von Moltke, a great-grandnephew of the celebrated army commander of the Franco-Prussian War, who worked in the Wehrmacht dubbed the Kreisau Circle after the estate owned by the Moltke family in Silesia, although it met there only two or three times. Its intense discussions, conducted in working groups, took place more frequently in various locations in Berlin; beginning in early 1943 most were held on Hortensienstrasse in Lichterfelde, at the home of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, another bearer of a famous name in Prussian history... While Moltke has been described as the "engine" of the group, Yorck von Wartenburg was its "heart".

Around Moltke and Yorck gathered what at first glance appeared to be a motley array of strong-willed individuals with markedly different origins, temperaments, and convictions... The most striking characteristic of this group, apart from its strong religious leanings, was its earnest and quite successful attempt to attract a number of devoted but undogmatic socialists...

A number of figures from the Christian resistance also joined the Kreisau Circle, including the Jesuits Alfred Delp and Augustin Rösch, as well as prominent Protestants like the theologian Eugen Gerstenmaier and the prison chaplain Harald Poelchau. Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and Julius Leber were also loosely affiliated with this group...

There was a strong utopian streak in their thought and planning, which was infused with Christian and socialist ideals, as well as remnants from the youth movement of a romantic belief in the dawning of a new era. They basically believed that all social and political systems were reaching a dead end and that capitalism and Communism, no less than Nazism, were symptomatic of the crisis deep and all encompassing in modern mass society.

(2) Peter Hoffmann, The History of German Resistance (1977)

Although the Kreisau Circle was at one on a number of principles, these were so broadly stated that much was left in the air, primary for the sake of agreement. The Circle was so named after Graf von Moltke's estate where the group frequently met. It had no established leader, however, and more often met in Berlin, though not in full conclave; it consisted of of highly independent personalities holding views of their own. They were both able and willing to compromise, for they knew that politics without compromise was impossible. In the discussion phase, however, they clung to their own views.

(3) Anton Gill, An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994)

The name the Gestapo gave it (the Kreisau Circle) is misleading, for it gives the impression of an organised, coherent group, with definite aims. This is not true. The circle, which met formally at Kreisau only three times, was a large, loosely knit group of people who came mainly from the young landowning aristocracy, the Foreign Office, the Civil Service, the old Social Democratic Party and the Church. Its membership shifted and changed, and for a long time its leaders were averse to taking action of any kind against Hitler, preferring instead to let him run his course - a matter which they considered inevitable - while in the meantime they discussed what sort of Germany they would rebuild after his equally inevitable fall...

There were perhaps twenty core members of the circle, and they were all relatively young men. Half were under thirty-six and only two were over fifty. The young landowning aristocrats had left-wing ideals and sympathies and created a welcome haven for leading Social Democrats who had elected to stay like the journalist-turned-politician Carlo Mierendorff, and... Julius Leber, were the political leaders of the group, and their ideas struck lively sparks off older members of the Resistance like Goerdeler.