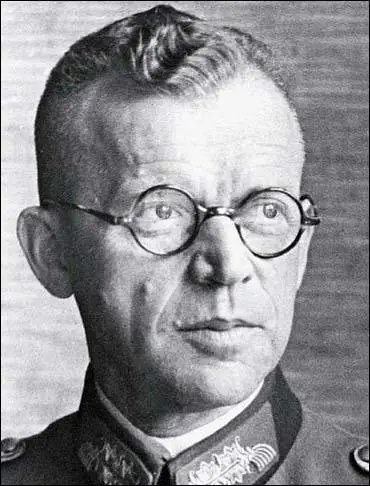

Erich Fellgiebel

Erich Fellgiebel was born in Pöpelwitz on 4th October 1886. At the age of 18, he joined a signals battalion in the Prussian Army as an officer cadet. During the First World War, he served as a captain on the General Staff. After the war he was assigned to Berlin as a General Staff officer of the Reichswehr and in 1928 he reached the rank of major. (1)

In 1933 Fellgiebel was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and became a full Colonel (Oberst) the following year. By 1938, he was a Major General. That year, he was appointed Chief of the Army's Signal Establishment and Chief of the Wehrmacht's communications liaison to the Supreme Command. In this role he became close to General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel and Colonel-General Ludwig Beck. All three men gradually became disillusioned with Adolf Hitler. (2)

In January, 1942, a group of men that included Stülpnagel and Beck developed a conspiracy to overthrow Hitler called Operation Valkyrie. Other members included Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, General Friedrich Olbricht, General-Major Henning von Tresckow, General Paul von Hase, Lieutenant Fabian Schlabrendorff, Wolf-Heinrich Helldorf, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, General-Major Hans Oster, Wilhelm Leuschner, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Dohnanyi, Carl Langbehn, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Helmuth von Moltke, Peter von Wartenburg, Johannes Popitz and Jakob Kaiser. (3)

According to Hans Gisevius, who was also a member, during 1942, several senior military officers, joined Operation Valkyrie. This included Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, General Eduard Wagner, General Fritz Lindemann, Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, Lieutenant Werner von Haeften, Colonel Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, and Colonel-General Erich Hoepner. "These generals, either because of their strength of numbers, their key positions for a revolt, or because of the recognition that the fate of the class was at stake, began to feel an increasing sense of unity." (4)

On 1st July 1944 Claus von Stauffenberg was promoted to Colonel and became Chief of Staff to General Friedrich Fromm. Stauffenberg was now in a position where he would have regular meetings with Adolf Hitler. Fellow conspirator, Henning von Tresckow sent a message to Stauffenberg: "The assassination must be attempted, at any cost. Even should that fail, the attempt to seize power in the capital must be undertaken. We must prove to the world and to future generations that the men of the German Resistance movement dared to take the decisive step and to hazard their lives upon it. Compared with this, nothing else matters." (5)

An agreement was reached with General Fellgiebel, the chief army signal officer, to interrupt signal traffic to and from Hitler's headquarters at a given moment. "But Fellgiebel had pointed out on several occasions that little could be done in advance because although there was a central communications center, the army, the air force, the SS, and the Foreign Office each had their own signal lines. In addition, care would have to be taken not to cut off signals to and from the troops at the front. Thus, Fellgiebel maintained, Führer headquarters could only be isolated for a limited period; everything depended, he said, on doing exactly the right thing at exactly the right time." (6)

On 20th July, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and Werner von Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived." (7)

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (8)

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (9)

Stauffenberg and Haeften observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. They got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let them go. (10)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (11)

Adolf Hitler, seized by a "titanic fury and an Unquenchable thirst for revenge" ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (12)

General Fellgiebel was arrested and was severely beaten, ill-treated and tortured but did not reveal any names of his co-conspirators. Most of those involved in the July Plot were executed on the day they were sentenced. However, Fellgiebel had to wait until 4th September, 1944, before he was put to death at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. (13)

Primary Sources

(1) Hans Gisevius, Valkyrie: An Insider's Account of the Plot to Kill Hitler (2009)

It is not at all by chance that a tightly knit group of officers, all firmly resolved to direct events, first coalesced in 1942, and grew in number and determination with each successive defeat. Generals von Tresckow, Olbricht, and Fellgiebel began it; in 1943 they were joined by Count Stauffenberg and Colonel Merz von Quirnheim; toward the end of the year by General Stieff and still later by Quartermaster-General Eduard Wagner and General Lindemann; finally Kluge and Colonel-General Hoeppner fell in line; and last of all came Field Marshal Rommel. These generals, either because of their strength of numbers, their key positions for a revolt, or because of the recognition that the fate of the class was at stake, began to feel an increasing sense of unity.

(2) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997)

An agreement was reached with General Fellgiebel, the chief army signal officer, to interrupt signal traffic to and from Hitler's headquarters at a given moment. But Fellgiebel had pointed out on several occasions that little could be done in advance because although there was a central communications center, the army, the air force, the SS, and the Foreign Office each had their own signal lines. In addition, care would have to be taken not to cut off signals to and from the troops at the front. Thus, Fellgiebel maintained, Fuhrer headquarters could only be isolated for a limited period; everything depended, he said, on doing exactly the right thing at exactly the right time. Meanwhile, however, improvements were to be made in communications with the liaison officers in the military districts, whose cooperation would be so essential to Operation Valkyrie; the preparedness of the army units in the Berlin area to take fast action had to be ensured; and numerous other aspects of mobilization, which was largely in Olbricht's hands, needed to be clarified. The final problem facing Stauffenberg was how to handle the pliers for igniting the bomb, which had to be specially constructed for him because of his mutilated hand.