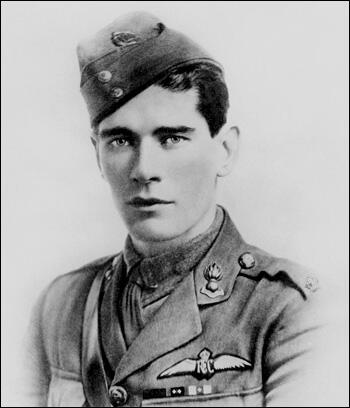

Mick Mannock

Edward 'Mick' Mannock, the son of Edward and Julia Mannock, was born at Preston Barracks, Brighton on 24th May 1887. Edward Mannock was a corporal in the Royal Scots regiment and the family was constantly on the move. As a child Mick lived in England, Scotland, Ireland and India.

While in India, Mick picked up an infection and went blind. Eventually he recovered his sight but for the rest of his life he had difficulty seeing out of his left eye. After Edward Mannock returned from the Boer War he deserted his wife and four children. Mick, who had suffered from his father's drunken rages, later revealed that he was pleased when he heard that his father had left the family home. However, the family were now very poor and Mick had to abandon his schooling at the earliest opportunity in order to bring in some much needed money. After a series of menial jobs, Mick found work as a telephone engineer.

Socialist

Mick became interested in politics and as a young man became a committed socialist. Jim Eyles, a close friend later said that: "Mick told everyone he met that every man should prepare himself for the new age. The downtrodden of the world were about to get their chance at last; it was a duty for men to make the best of this opportunity for which the up-and-coming leaders of the new ideas had suffered so much." Mick spoke at political meetings and Jim Eyes later remarked how surprised he was that this young man "who had been dragged up in the most awful squalor, could match wits with these high-born and well-educated classes."

Turkey

In February 1914, Mick Mannock's employers, the National Telephone Company, sent him to work in Turkey. When war was declared on 4th August 1914, Mick attempted to get back to England. Turkey had formed a defence alliance with Germany and Mick realised he was in danger. However, before he could arrange transport, Mick was arrested by the Turkish authorities and put into a concentration camp. After several attempts at escape, which resulted in long periods of solitary-confinement in a 6ft. cage, Mick was eventually allowed to leave for England in April 1915.

British Army

As soon as Mick Mannock arrived back home he joined the British Army. He was soon promoted to the rank of sergeant-major, but his health was poor and the army considered him unfit for military duties. In March 1916 he managed to obtain a transfer to the Royal Engineers as an officer cadet. Although he had very little formal schooling, Mick found he could compete with his well educated companions and was not long before he achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant.

Royal Flying Corps

In the summer of 1916, Mannock began reading in the newspapers about the exploits of Albert Ball, Britain's leading flying ace. Ball, who was not yet twenty years old, had already shot down eleven German aircraft. Mannock asked for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps and in August 1916, he was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics in Reading.

Mannock had a natural aptitude for flying. Captain Chapman, one of the men responsible for training Mick, later reported that: " He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased." Captain James McCudden, who was later to become one of Britain's leading flying aces, was another instructor who was impressed with Mick Mannock's skills as a pilot.

Western Front

In March 1917, it was decided that Mannock was ready to be sent to the Western Front. Mannock arrived at St. Omer in France on 6th April 1917. At first Mannock's personality and political opinions upset the other pilots. Lieutenant Lional Blaxland later recalled his first impression of Mannock: "He was different. His manner, speech and familiarity were not liked. New men usually took their time and listened to the more experienced hands; Mannock was the complete opposite. He offered ideas about everything: how the war was going, how it should be fought, the role of scout pilots, what was wrong or right with our machines. Most men in his position, by that I mean a man with his background, would have shut up."

Soon after arriving in France, Mannock heard the news that Albert Ball, the man whose example had inspired him to join the Royal Flying Corps, had been shot down and killed. The same day, Captain Nixon, Mannock's patrol leader, was also killed during a mission to destroy German observation balloons.

Mannock had difficulty adjusting to combat duties and he had to wait until the 7th June 1917 before he made his first confirmed 'kill'. Before he could add to his total he received a wound to the head during a dogfight with two German pilots.

Mannock was sent back to England to recover. Mick went to stay with his mother but was dismayed to find that his mother, like his father, was now an alcoholic. He also discovered that his sister, Jessie, was working as a prostitute in Birmingham. Upset by the state of his family, Mick was anxious to get back to France, and desperately short of trained pilots, the RFC agreed that he could return to duty.

Military Cross

After returning to France in July, Mannock quickly developed a reputation as one of the most talented pilots in the RFC. In the first two weeks after arriving back at the Western Front he won four dogfights in his SE-5a. This gave him new confidence and on the 16th August he shot down four aircraft in a day. The following morning he added two more victories to his total. On the 17th September he won the Military Cross for driving off several enemy aircraft while destroying three German observation balloons. The following month he was awarded a bar to his Military Cross. The official citation read: "He attacked a formation of five enemy machines single-handed and shot one down out of control; while engaged with an enemy machine, he was attacked by two others, one of which he forced down to the ground."

Mannock was deeply affected by the amount of men he was killing. In his diary he recorded visiting the site where one of his victims had crashed near the front-line: "The journey to the trenches was rather nauseating - dead men's legs sticking through the sides with puttees and boots still on - bits of bones and skulls with the hair peeling off, and tons of equipment and clothing lying about. This sort of thing, together with the strong graveyard stench and the dead and mangled body of the pilot combined to upset me for a few days."

Mannock was especially upset when he saw one of his victims catch fire on its way to the ground. From that date on, Mick Mannock always carried a revolver with him in his cockpit. As he told his friend Lieutenant MacLanachan: "The other fellows all laugh at me for carrying a revolver. They think I'm going to shoot down a machine with it, but they're wrong. The reason I bought it was to finish myself as soon as I see the first signs of flames."

Campaign for Parachutes

Mannock's fear of fire was made worse by the British High Command's decision not to allow pilots in the Royal Flying Corps to carry parachutes. Mannock believed it was unfair to deny British airman to right to have parachutes when German pilots had been using them successfully for several months. He was especially angry about the main reason given for this decision: "It is the opinion of the board that the presence of such an apparatus might impair the fighting spirit of pilots and cause them to abandon machines which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair."

On 22nd July 1917, Mannock was promoted to captain. As flight commander he was able to introduce a new approach to combat flying. Mannock believed that the "days of the lone fighter was past and air fighting was now a matter for co-ordinated and planned fighting units which could inflict maximum damage and minimum losses."

In February 1918, Mannock became flight commander of 74 Squadron. The next three months saw thirty-six more victories. Mannock had now overtaken Albert Ball's total of forty-four kills and on 20th July he shot down a Albatros giving him fifty-eight victories, one more than the British record held by James McCudden. In June he was promoted to the rank of major and the following month became commander of 85 Squadron.

On 26th July, Major Mannock offered to help a new arrival, Donald Inglis, obtain his first victory. After shooting down an Albatros behind the German front-line, the two men headed for home. While crossing the trenches, the fighters were met with a massive volley of ground-fire. The engine of Mannock's aircraft was hit and immediately caught fire and crashed behind German lines. Mannock's body was found 250 yards from the wreck of his machine. He did not fire his revolver but it is believed he might have jumped from his blazing plane just before it crashed.

Victoria Cross

After his death, Mick Mannock was awarded the Victoria Cross for: "an outstanding example of fearless courage, remarkable skill, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice which has never been surpassed". Mannock's Victoria Cross was presented to his father at Buckingham Palace in July 1919. Edward Mannock was also given his son's other medals, even though Mick had stipulated in his will that his father should receive nothing from his estate. Soon afterwards Mannock's medals were sold for £5. They have since been recovered and can be seen at the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon.

Primary Sources

(1) Jim Eyles first met Mick Mannock when he was twenty-four.

I first met Mick at a cricket match in Wellingborough. I was impressed with him immediately. He was a clean-cut young man, although not what one would call well dressed; in fact, he was a bit threadbare. I asked him if he would like to move in with my wife and myself, and he was most happy about the idea. After he moved in, our home was never the same again, our normally quiet life gone forever. It was wonderful really. He would talk into the early hours of the morning if you let him - all sorts of subjects: politics, society, you name it and he was interested. It was clear from the outset he was a socialist. He was also deeply patriotic. A kinder, more thoughtful man you could never meet.

(2) Captain Chapman was one of Mick Mannock's teachers at the School of Military Aeronautics. He later described Mick Mannock's early training.

When he arrived he seemed not to have the slightest conception of an aeroplane. The first time we took off the ground, Mannock, unlike many pupils, instead of jamming the rudder and seizing the joystick in a herculean grip, looked over the side of the aeroplane at the earth, which was dropping rapidly away from him, with an expression which betrayed the mildest interest. He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased.

(3) Keith Caldwell was Major Mick Mannock's squadron leader during the First World War. In an interview he gave in 1981, Caldwell explained why Mannock was such a successful pilot.

Mannock was an extraordinarily good shot and a very good strategist, he could place his flight team high against the sun and lead them into a favourable position where they would have the maximum advantage. Then he would go quickly on the enemy, slowing down at the last possible moment to ensure that each of his followers got into a good firing position.

(4) H. G. Clements wrote an account of Major Mick Mannock in 1981.

The fact that I am still alive is due to Mick's high standard of leadership and the strict discipline on which he insisted. We were all expected to follow and cover him as far as possible during an engagement and then to rejoin the formation as soon as that engagement was over. None of Mick's pilots would have dreamed of chasing off alone after the retreating enemy or any other such foolhardy act. He moulded us into a team, and because of his skilled leadership we became a highly efficient team. Our squadron leader said that Mannock was the most skillful patrol leader in World War I, which would account for the relatively few casualties in his flight team compared with the high number of enemy aircraft destroyed.

(5) Lieutenant MacLanachan met Mick Mannock in May 1917. After the war MacLanachan wrote about his experiences in his book Fighter Pilot.

Mick was twenty-eight or twenty-nine when I met him for the first time. He had then been two months in France. Everything about him demonstrated his vitality, a strong, manly man. His alert brain was quick, and an unbroken courage and straightforward character forced him to take action where others would sit down uncomprehending. I was awed by his personality.

(6) Jim Eyles later recalled Mick Mannock's last leave before his death.

I well remember his last leave. Gone was the old sparkle we knew so well; gone was the incessant wit. I could see him wringing his hands together to conceal the shaking and twitching, and then he would leave the room when it became impossible for him to control it. On one occasion we were sitting in the front talking quietly when his eyes fell to the floor, and he started to tremble violently. He cried uncontrollably. His face, when he lifted it, was a terrible sight. Later he told me that it had just been a 'bit of nerves' and that he felt better for a good cry. He was in no condition to return to France, but in those days such things were not taken into account.

(7) An extract from Mick Mannock's last letter to Jim Eyles.

I feel that life is not worth hanging on to. I had hopes of getting married, but not now.

(8) Lieutenant Donald Inglis was with Mick Mannock when he was shot down.

Mick fired at a two-seater. He must have got the observer, as the Hun stopped shooting. I fired and hit the Hun's petrol-tank. Falling in behind Mick again, we did a couple of turns over the burning wreck and then made for home. We were fairly low, then I saw a flame come out of the side of his machine; it grew bigger and bigger. He went into a slow right-hand turn, about twice, and hit the ground in a burst of flame.

(9) Private Naulls was in the front trenches when he saw Mannock's aircraft brought down.

There was a lot of rifle-fire from the Jerry trenches, and a machine-gun near Robecq opened up, using tracers. I saw these strike Mannock's engine. A blueish-white flame appeared and spread rapidly; smoke and flames enveloped the engine and cockpit.