Royal Flying Corps

Military aviation in Britain began in 1878 when the Royal Engineers formed a Balloon unit. However, it was not until 1907 that a powered army airship became operational. The first Air Battalion was established in 1911. At first progress was slow and by 1912 the Air Battalion only had eleven qualified pilots compared to 263 in the French Army Air Service.

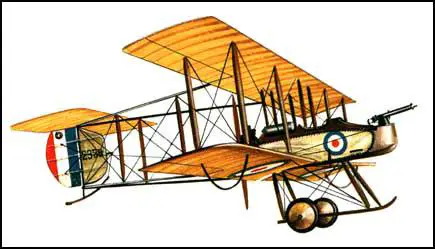

Great Britain founded the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in May 1912. It was decided that initially the BE-2 would be the main fighter plane. By the end of 1912 the RFC had one squadron of airships and three of aircraft. Each squadron had twelve machines.

At the beginning of the war the RFC mainly used the BE-2, Farman MF-7, Avro 504, Vickers FB5, Bristol Scout, and the F.E.2. By May 1915, the Royal Flying Corps had 166 aircraft. Therefore the vast majority of the operations on the Western Front was carried out by the Aéronautique Militaire, which had 1,150 aircraft available.

In August 1915 Hugh Trenchard became the new RFC field commander. Trenchard took a much more aggressive approach and insisted on non-stop offensive patrols over enemy lines. British casualties were high, and by 1916, an average of two aircrew crew were lost every day. It became even worse the following year, and in the spring of 1917 the RFC were losing nearly fifty aircraft a week.

By the time the Battle of the Somme started in July 1916 the RFC had a total strength of twenty-seven squadrons (421 aircraft), with four kite-balloon squadrons and fourteen balloons. The squadrons were organised into four brigades, each of which worked with one of the British armies.

It was only with the arrival of improved fighter planes such as the Bristol Fighter, Sopwith Pup, Sopwith Camel, S.E.5 and Airco DH-2 that losses began to decline. Britain also developed new bombers such as the Handley Page and Airco DH-4. By the end of 1917 the British has established their superiority over the German airforce.

General Hugh Trenchard, the RFC field commander in France, was a strong supporter of strategic bombing. Eventually, in January 1918, Trenchard was appointed chief of staff to the Royal Air Force with the promise of being able to create a mass bombing fleet of aircraft. By the end of the war the RAF operated 4,000 combat aircraft and employed 114,000 people.

Primary Sources

(1) Harold Chapin, letter to Alice Chapin (2nd April 1915)

Aeroplanes are every day - almost every hour - occurrences, and bombs are dropped here and there about the country in general in charming profusion. They seem to do amazingly slight damage - especially to the military (either men or works). The civil population suffer slightly but apparently no more than does the London public from traffic and fires.

(2) Captain Chapman was one of Mick Mannock's teachers at the School of Military Aeronautics. He later described Mick Mannock's early training.

When he arrived he seemed not to have the slightest conception of an aeroplane. The first time we took off the ground, Mannock, unlike many pupils, instead of jamming the rudder and seizing the joystick in a herculean grip, looked over the side of the aeroplane at the earth, which was dropping rapidly away from him, with an expression which betrayed the mildest interest. He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased.