Battle of the Somme

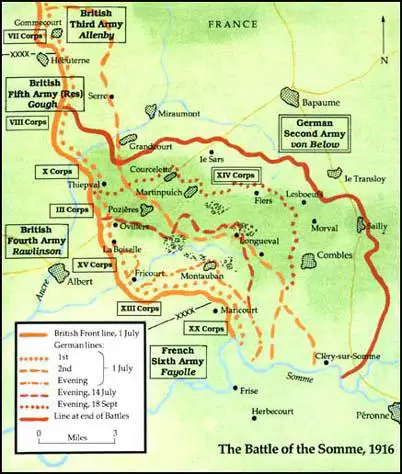

The Battle of the Somme was planned as a joint French and British operation. The idea originally came from the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre and was accepted by General Douglas Haig, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commander, despite his preference for a large attack in Flanders. Although Joffre was concerned with territorial gain, it was also an attempt to destroy German manpower.

Morale in Britain was at an all-time low. "Haig needed a breakthrough to boost the flagging spirits of a country still in principle fully behind the war, patriotic and pressing for military victory." After a meeting with the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre, it was decided to mount a joint offensive where the British and French lines joined on the Western Front. (1) According to Basil Liddell Hart, the decision by Joffre to make this sector, considered to be the German's strongest, "seems to have been arrived at solely because the British would be bound to take part in it." (2)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, was told about the plan when he visited General Haig in May 1916. He agreed to give his full support in his newspapers to the offensive. One of his biographers, S. J. Taylor, points out: "Northcliffe... at last capitulated, the Daily Mail descending into the propagandistic prose that came to characterize the reporting of the First World War. It was a style long since adopted by his competitors; stirring phrases, empty words, palpable lies." (3)

At first Joffre intended for to use mainly French soldiers but the German attack on Verdun in February 1916, turned the Somme offensive into a large-scale British diversionary attack. General Haig now took over responsibility for the operation and with the help of General Sir Henry Rawlinson, came up with his own plan of attack. Haig's strategy was for a eight-day preliminary bombardment that he believed would completely destroy the German forward defences. He told his General Staff that "the advance was to be pressed eastward far enough to enable our cavalry to push through into the open country beyond the enemy's prepared lines of defence." (4)

General Haig wrote that he was convinced that the offensive would win the war: "I feel that every step in my plan has been taken with the Divine help". (5) General Henry Rawlinson was was in charge of the main attack and his Fourth Army were expected to advance towards Bapaume. To the north of Rawlinson, General Edmund Allenby and the British Third Army were ordered to make a breakthrough with cavalry standing by to exploit the gap that was expected to appear in the German front-line. Further south, General Émile Fayolle was to advance with the French Sixth Army towards Combles. Rawlinson wrote: "DG (Haig) tells me that we are to attack, that the French are doing likewise and making a supreme effort. It will cost us dearly, and we shall not get very far." (6)

The Battle of the Somme began in early hours of the 1st July 1916, when nearly a quarter of a million shells were fired at the German positions in just over an hour, an average of 3,500 a minute. So intense was the barrage that it was heard in London. At 7.28 a.m. ten mines were exploded under the German trenches. Two minutes later, British and French troops attacked along a 25-mile front. The main objective was "to break through the German lines by means of a massive infantry assault, to try to create the conditions in which cavalry could then move forward rapidly to exploit the breakthrough." (7)

On the first day of the battle thirteen British divisions went "over the top" in regular waves. The bombardment failed to destroy either the barbed-wire or the concrete bunkers protecting the German soldiers. This meant that the Germans were able to exploit their good defensive positions on higher ground. "The attack was a total failure. The barrage did not obliterate the Germans. Their machine guns knocked the British over in rows: 19,000 killed, 57,000 casualties sustained - the greatest loss in a single day ever suffered by a British army and the greatest suffered by any army in the First World War. Haig had talked beforehand of breaking off the offensive if it were not at once successful. Now he set his teeth and kept doggedly on - or rather, the men kept on for him." (8)

Haig was helped in this by newspapers reporting that the offensive was a success. William Beach Thomas, in The Daily Mail, under the headline, "Enemy Outgunned", wrote: "We are laying siege not to a place but to the German Army - that great engine which had at last mounted to its final perfection and utter lust of dominion. In the first battle, we have beaten the Germans by greater dash in the infantry and vastly superior weight in munitions." (9) In a later report he claimed: The very attitudes of the dead, fallen eagerly forwards, have the look of expectant hope. You would say they died with the light of victory in their eyes." (10)

General Douglas Haig continued to order further attacks on German positions at the Somme and on the 13th November the British Army captured the fortress at Beaumont Hamel. However, heavy snow forced Haig to abandon his gains. With the winter weather deteriorating Haig now brought an end to the Somme offensive. Since the 1st July, the British has suffered 420,000 casualties. The French lost nearly 200,000 and it is estimated that German casualties were in the region of 500,000. Allied forces gained some land but it reached only 12km at its deepest points. Despite mounting criticism over his seeming disregard of British lives, Haig survived as Commander-in-Chief. One of the main reasons for this was the support he received from Northcliffe's newspapers. (11)

General William Robertson continued to support Haig's tactics. Robertson's biographer, David R. Woodward, has pointed out: "British losses on the first day of the Somme offensive - almost 60,000 casualties - shocked Robertson. Haig's one-step breakthrough attempt was the antithesis of Robertson's cautious approach of exhausting the enemy with artillery and limited advances. Although he secretly discussed more prudent tactics with Haig's subordinates he defended the BEF's operations in London. The British offensive, despite its limited results, was having a positive effect in conjunction with the other allied attacks under way against the central powers. The continuation of Haig's offensive into the autumn, however, was not so easy to justify." (12)

Haig was not disheartened by these heavy losses on the first day and ordered General Sir Henry Rawlinson to continue making attacks on the German front-line. A night attack on 13th July did achieve a temporary breakthrough but German reinforcements arrived in time to close the gap. Haig believed that the Germans were close to the point of exhaustion and continued to order further attacks expected each one to achieve victory. Although small gains were achieved, for example, the capture of Pozieres on 23rd July, they could not be successfully followed up.

Captain Charles Hudson was one of those officers who took part in the battle. He later wrote: "It is difficult to see how Haig, as Commander-in-Chief living in the atmosphere he did, so divorced from the fighting troops, could fulfil the tremendous task that was laid upon him effectively. I did not believe then, and I do not believe now that the enormous casualties were justified. Throughout the war huge bombardments failed again and again yet we persisted in employing the same hopeless method of attack. Many other methods were possible, some were in fact used but only half-heartedly." (13)

Private James Lovegrove was also highly critical of Haig's tactics: "The military commanders had no respect for human life. General Douglas Haig... cared nothing about casualties. Of course, he was carrying out government policy, because after the war he was knighted and given a lump sum and a massive life-pension. I blame the public schools who bred these ego maniacs. They should never have been in charge of men. Never."

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985), has argued that Brigadier-General John Charteris, the Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ. was partly responsible for this disaster: "Charteris's intelligence reports throughout the five-month battle were designed to maintain Haig's morale. Though one of the intelligence officer's duties may be to help maintain his commander's morale, Charteris crossed the frontier between optimism and delusion." As late as September 1916, Charteris was telling General Haig: "It is possible that the Germans may collapse before the end of the year." (14)

On 15th September General Alfred Micheler and the Tenth Army joined the battle in the south at Flers-Courcelette. Despite using tanks for the first time, Micheler's 12 divisions gained only a few kilometres. Whenever the weather was appropriate, General Sir Douglas Haig ordered further attacks on German positions at the Somme and on the 13th November the BEF captured the fortress at Beaumont Hamel. However, heavy snow forced Haig to abandon his gains.

With the winter weather deteriorating Haig now brought an end to the Somme offensive. Since the 1st July, the British has suffered 420,000 casualties. The French lost nearly 200,000 and it is estimated that German casualties were in the region of 500,000. Allied forces gained some land but it reached only 12km at its deepest points. Haig wrote at the time: "The results of the Somme fully justify confidence in our ability to master the enemy's power of resistance." (15)

During the First World War a total of 634 awards of the Victoria Cross were made, of which fifty-one were for the Battle of the Somme. "The spread of ranks who won the medal is a fairly wide one, with twenty going to officers, twelve to non-commissioned officers, and nineteen going to privates or their equivalent... A third of the Somme VCs were awarded posthumously and only thirty-three men survived the war." (16)

In the 1920s Haig was severely criticised for the tactics used at offensives such as the one at the Somme. This included the prime minister of the time, David Lloyd George: "It is not too much to say that when the Great War broke out our Generals had the most important lessons of their art to learn. Before they began they had much to unlearn. Their brains were cluttered with useless lumber, packed in every niche and corner. Some of it was never cleared out to the end of the War. They knew nothing except by hearsay about the actual fighting of a battle under modern conditions. Haig ordered many bloody battles in this War. He only took part in two. He never even saw the ground on which his greatest battles were fought, either before or during the fight. The tale of these battles constitutes a trilogy, illustrating the unquestionable heroism that will never accept defeat and the inexhaustible vanity that will never admit a mistake." (17)

Duff Cooper, who was commissioned by the Haig family to write his official biography, argued: "There are still those who argue that the Battle of the Somme should never have been fought and that the gains were not commensurate with the sacrifice. There exists no yardstick for the measurement of such events, there are no returns to prove whether life has been sold at its market value. There are some who from their manner of reasoning would appear to believe that no battle is worth fighting unless it produces an immediately decisive result which is as foolish as it would be to argue that in a prize fight no blow is worth delivering save the one that knocks the opponent out. As to whether it were wise or foolish to give battle on the Somme on the first of July, 1916, there can surely be only one opinion. To have refused to fight then and there would have meant the abandonment of Verdun to its fate and the breakdown of the co-operation with the French." (18)

Primary Sources

(1) After the war, Sir William Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, attempted to explain the strategy at the Battle of the Somme.

Remembering the dissatisfaction displayed by ministers at the end of 1915 because the operations had not come up to their expectations, the General Staff took the precaution to make quite clear beforehand the nature of the success which the Somme campaign might yield. The necessity of relieving pressure on the French Army at Verdun remains, and is more urgent than ever. This is, therefore, the first objective to be obtained by the combined British and French offensive. The second objective is to inflict as heavy losses as possible upon the German armies.

(2) Sir Douglas Haig, battle orders sent out just before the Battle of the Somme (May 1916)

The First, Second, and Third Armies will take steps to deceive the enemy as to the real front of attack, to wear him out, and reduce his fighting efficiency both during the three days prior to the assault and during the subsequent operations. Preparations for deceiving the enemy should be made without delay. This will be effected by means of -

(a) Preliminary preparations such as advancing our trenches and saps, construction of dummy assembling trenches, gun emplacements, etc.

(b) Wire cutting at intervals along the entire front with a view to inducing the enemy to man his defences and causing fatigue.

(c) Gas discharges, where possible, at selected places along the whole British front, accompanied by a discharge of smoke, with a view to causing the enemy to wear his gas helmets and inducing fatigue and causing casualties.

(d) Artillery barrages on important communications with a view to rendering reinforcements, relief, and supply difficult.

(e) Bombardment of rest billets by night.

(f) Intermittent smoke discharges by day, accompanied by shrapnel fire on the enemy's front defences with a view to inflicting loss.

(g) Raids by night, of the strength of a company and upwards, on an extensive scale, into the enemy's front system of defences. These to be prepared by intense artillery and trench-mortar bombardments.

(3) George Mallory, was the commander of the 40th Siege Battery at the Somme. He wrote a letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory on 2nd July, 1916.

Our part was to keep up a barrage fire on certain lines, "lifting" after certain fixed times from one to another more remote and so on. Of course we couldn't know how matters were going for several hours. But then the wounded - walking cases - began to pass and bands of prisoners. We heard various accounts but it seemed to emerge pretty clearly that the attack was held up somewhere by machine-gun fire and this was confirmed by the nature of our own tasks after the "barrage" was over. To me, this result together with the sight of the wounded was poignantly grievous. I spent most of the morning in the map room by the roadside, standing by to help Lithgow (the Commanding Officer) to get onto fresh targets.

(4) Sir Douglas Haig explained the importance of using heavy artillery at the Battle of the Somme in his book Dispatches, that was published after the war.

The enemy's position to be attacked was of a very formidable character, situated on a high, undulating tract of ground. The first and second systems each consisted of several lines of deep trenches, well provided with bomb-proof shelters and with numerous communication trenches connecting them. The front of the trenches in each system was protected by wire entanglements, many of them in two belts forty yards broad, built of iron stakes, interlaced with barbed-wire, often almost as thick as a man's finger. Defences of this nature could only be attacked with the prospect of success after careful artillery preparation.

(5) Philip Gibbs, a journalist, watched the preparation for the major offensive at the Somme in July, 1916.

Before dawn, in the darkness, I stood with a mass of cavalry opposite Fricourt. Haig as a cavalry man was obsessed with the idea that he would break the German line and send the cavalry through. It was a fantastic hope, ridiculed by the German High Command in their report on the Battles of the Somme which afterwards we captured.

In front of us was not a line but a fortress position, twenty miles deep, entrenched and fortified, defended by masses of machine-gun posts and thousands of guns in a wide arc. No chance for cavalry! But on that night they were massed behind the infantry. Among them were the Indian cavalry, whose dark faces were illuminated now and then for a moment, when someone struck a match to light a cigarette.

Before dawn there was a great silence. We spoke to each other in whispers, if we spoke. Then suddenly our guns opened out in a barrage of fire of colossal intensity. Never before, and I think never since, even in the Second World War, had so many guns been massed behind any battle front. It was a rolling thunder of shell fire, and the earth vomited flame, and the sky was alight with bursting shells. It seemed as though nothing could live, not an ant, under that stupendous artillery storm. But Germans in their deep dugouts lived, and when our waves of men went over they were met by deadly machine-gun and mortar fire.

Our men got nowhere on the first day. They had been mown down like grass by German machine-gunners who, after our barrage had lifted, rushed out to meet our men in the open. Many of the best battalions were almost annihilated, and our casualties were terrible.

A German doctor taken prisoner near La Boiselle stayed behind to look after our wounded in a dugout instead of going down to safety. I met him coming back across the battlefield next morning. One of our men were carrying his bag and I had a talk with him. He was a tall, heavy, man with a black beard, and he spoke good English. "This war!" he said. "We go on killing each other to no purpose. It is a war against religion and against civilisation and I see no end to it."

(6) Statement issued by the British Army based in Paris on the Somme Offensive (3rd July, 1916)

The first day of the offensive is very satisfactory. The success is not a thunderbolt, as has happened earlier in similar operations, but it is important above all because it is rich in promises. It is no longer a question here of attempts to pierce as with a knife. It is rather a slow, continuous, and methodical push, sparing in lives, until the day when the enemy's resistance, incessantly hammered at, will crumple up at some point. From to-day the first results of the new tactics permit one to await developments with confidence.

(7) Private George Morgan, Ist Bradford Pals, took part in the Battle of the Somme on the 1st July, 1916.

There was no lingering about when zero hour came. Our platoon officer blew his whistle and he was the first up the scaling ladder, with his revolver in one hand and a cigarette in the other. "Come on, boys," he said, and up he went. We went up after him one at a time. I never saw the officer again. His name is on the memorial to the missing which they built after the war at Thiepval. He was only young but he was a very brave man.

(8) John Irvine, Daily Express (3rd July, 1916)

A perceptible slackening of our fire soon after seven was the first indication given to us that our gallant soldiers were about to leap from their trenches and advance against the enemy. Non-combatants, of course, were not permitted to witness this spectacle, but I am informed that the vigour and eagerness of the first assault were worthy of the best traditions of the British Army.

We had not to wait long for news, and it was wholly satisfactory and encouraging. The message received at ten o'clock ran something like this: "On a front of twenty miles north and south of the Somme we and our French allies have advanced and taken the German first line of trenches. We are attacking vigorously Fricourt, La Boiselle, and Mametz. German prisoners are surrendering freely, and a good many already fallen into our hands.

(9) William Beach Thomas, With the British on the Somme (1917)

No true news (of the first day of the Battle of the Somme) was known by anyone for hours. Flashes of hope, half-lights of expectation, hints of calamity only penetrated the smoke and dust and bullets that smothered the trenches. The tension was unendurable. The telephones, the carrier pigeons, the guesses of direct observers, the records of the runers, the glimpses of the air-men, all combined could scarcely penetrate the fog of war. The wounded who struggled back from the German trenches themselves knew little.

(10) The Daily Chronicle (3rd July, 1916)

Ist July, 1916: At about 7.30 o'clock this morning a vigorous attack was launched by the British Army. The front extends over some 20 miles north of the Somme. The assault was preceded by a terrific bombardment, lasting about an hour and a half. It is too early to as yet give anything but the barest particulars, as the fighting is developing in intensity, but the British troops have already occupied the German front line. Many prisoners have already fallen into our hands, and as far as can be ascertained our casualties have not been heavy.

(11) Herbert Russell, sent a telegram to Reuters about the Battle of the Somme (1st July, 1916)

Good progress into enemy territory. British troops were said to have fought most gallantly and we have taken many prisoners. So far the day is going well for Great Britain and France.

(12) George Mallory, was the commander of the 40th Siege Battery at the Somme. He wrote a letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory on 15th August, 1916.

I don't object to corpses so long as they are fresh - I soon found that I could reason thus with them. Between you and me is all the difference between life and death. But this is an accepted fact that men are killed and I have no more to learn about that from you, and the difference is no greater than that because your jaw hangs and your flesh changes colour or blood oozes from your wounds. With the wounded it is different. It always distresses me to see them.

(13) George Coppard was a machine-gunner at the Battle of the Somme. In his book With A Machine Gun to Cambrai, he described what he saw on the 2nd July, 1916.

The next morning we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of our trench. There was a pair of binoculars in the kit, and, under the brazen light of a hot mid-summer's day, everything revealed itself stark and clear. The terrain was rather like the Sussex downland, with gentle swelling hills, folds and valleys, making it difficult at first to pinpoint all the enemy trenches as they curled and twisted on the slopes.

It eventually became clear that the German line followed points of eminence, always giving a commanding view of No Man's Land. Immediately in front, and spreading left and right until hidden from view, was clear evidence that the attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead, many of the 37th Brigade, were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high-water mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in the net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as though they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. From the way the dead were equally spread out, whether on the wire or lying in front of it, it was clear that there were no gaps in the wire at the time of the attack.

Concentrated machine gun fire from sufficient guns to command every inch of the wire, had done its terrible work. The Germans must have been reinforcing the wire for months. It was so dense that daylight could barely be seen through it. Through the glasses it looked a black mass. The German faith in massed wire had paid off.

How did our planners imagine that Tommies, having survived all other hazards - and there were plenty in crossing No Man's Land - would get through the German wire? Had they studied the black density of it through their powerful binoculars? Who told them that artillery fire would pound such wire to pieces, making it possible to get through? Any Tommy could have told them that shell fire lifts wire up and drops it down, often in a worse tangle than before.

(14) General Rees, commander of 94th Infantry Brigade at the Somme, described how his men went into battle on 1st July, 1916.

They advanced in line after line, dressed as if on parade, and not a man shirked going through the extremely heavy barrage, or facing the machine-gun and rifle fire that finally wiped them out. I saw the lines which advanced in such admirable order melting away under the fire. Yet not a man wavered, broke the ranks, or attempted to come back. I have never seen, I would never have imagined, such a magnificent display of gallantry, discipline and determination. The reports I have had from the very few survivors of this marvellous advance bear out what I saw with my own eyes, viz, that hardly a man of ours got to the German front line.

(15) German machine-gunner at the Somme.

The officers were in the front. I noticed one of them walking calmly carrying a walking stick. When we started firing we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn't have to aim, we just fired into them.

(16) John Buchan described the first day of the offensive at the Somme in his pamphlet, The Battle of the Somme (1916)

The British moved forward in line after line, dressed as if on parade; not a man wavered or broke ranks; but minute by minute the ordered lines melted away under the deluge of high explosives, shrapnel, rifle, and machine-gun fire. The splendid troops shed their blood like water for the liberty of the world.

(17) Harold Mellersh was a young platoon commander who took part in the Somme offensive.

Nothing happened at first. We advanced at a slow double. I noticed that it had begun to rain. Then the enemy machine-gunning started, first one gun, then many. They traversed, and every now and then there came the swish of bullets.

It's a bloody death trap, someone said. I told him to shut up. But was he right? We struggled on through the mud and the rain and the shelling. Then came a terrific crack above my head, a jolt in my left shoulder, and at the same time I was watching in an amazed, detached sort of way my right forearm twist upwards of its own volition and then hang limp. I realised that I had been hit.

I was suddenly filled with a surge of happiness. It was a physical feeling almost, consciousness of a reprieve from the shadow of death, no less. That I had just taken part in a failure, that I had really done nothing to help win the war, these things were forgotten - if ever indeed they had entered my consciousness.

(18) Clare Tisdall worked as a nurse at a Casualty Clearing Station during the Battle of the Somme.

During the Somme we practically never stopped. I was up for seventeen nights before I had a night in bed. A lot of the boys had legs blown off, or hastily amputated at the front-line. These boys were the ones who were in the greatest pain, and I very often used to have to hold the stump up in the ambulance for the whole journey, so that it wouldn't bump on the stretcher.

The worse case I saw - and it still haunts me - was of a man being carried past us. It was at night, and in the dim light I thought that his face was covered with a black cloth. But as he came nearer, I was horrified to realize that the whole lower half of his face had been completely blown off and what had appeared to be a black cloth was a huge gaping hole. It was the only time I nearly fainted.

(19) Ford Madox Ford served at Mametz Wood during the Battle of the Somme. He wrote about his experiences in his book, No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction (1929)

I don't think that many of those who were one's comrades did not at times feel a certain hopelessness. And so they would sit in the chairs of the lost and forgotten. You will say this is bitter. It Is. It was bitter to have seen the 38th Division murdered in Mametz Wood - and to guess what underlay that.

(20) In his pamphlet, The Battle of the Somme, John Buchan describes the Allied attack on German lines on 14th July.

The attack failed nowhere. In some parts if was slower than others, where the enemy's defence had been less comprehensively destroyed, but by the afternoon all our tasks had been accomplished. The audacious enterprise had been crowned with unparalleled success. Germans may write on their badges that God is with them, but our lads - they know.

(21) Manchester Guardian (18th September 1916)

The British army has struck the enemy another heavy blow north of the Somme. Attacking shortly after dawn yesterday morning on a front of more than six miles north-east from Combles, it now occupies a new strip of reconquered territory including three fortified villages behind the German third line and many local positions of great strength.

Fighting has continued since without intermission, and the initiative remains with our troops, who made further advances beyond Courcelette, Martinpuich, and Flers to-day. After the first shock yesterday morning, when the enemy surrendered freely, showing signs of demoralisation, there has been stubborn resistance, and much of the ground gained afterwards was only wrested from him by the determination and strength of the British battalions pitted against him. The Bavarian and German divisions have fought well, but nevertheless they have been steadily pushed backwards from the line they took up after their first defeats in the Somme campaign.

British patrols have approached Eaucourt l'Abbaye and Geudecourt, and while no definite information is obtainable to-night regarding the exact extent of our gains they are rather more than the territory described in detail in this despatch. The battle is not over. Famous British regiments are lying in the open to-night holding their position with the greatest heroism. All that the enemy can do in the way of artillery reprisals he is doing to-night. But despite the tenacity with which the reinforced German troops are clinging to their positions everything gained has been maintained. Progress may not be at the same speed as in the first assault yesterday morning, but it is thorough and none the less sure.

The story of the capture of Courcelette and Martinpuich, which were wrested from the Bavarians virtually street by street yesterday, will be as dramatic as any narrative told in this war. They are the chief episodes in the first two days of this offensive, but I can only give a bare summary now of the furious conflict which raged for possession of these obscure ruined villages. There are evidences that the unexpected British offensive disorganised the plans of the German higher command for an important counter-attack to recover the ground lost since July 1. Heavy concentrations of infantry were taking place, and the unusually strong resistance on the British left was due to the presence of an abnormal number of troops behind Martinpuich and Courcelette. In spite of this the divisions taking part in yesterday's attack splendidly achieved their purpose.

Armoured cars working with the infantry were the great surprise of this attack. Sinister, formidable, and industrious, these novel machines pushed boldly into "No Man's Land," astonishing our soldiers no less than they frightened the enemy. Presently I shall relate some strange incidents of their first grand tour in Picardy, of Bavarians bolting before them like rabbits and others surrendering in picturesque attitudes of terror, and the delightful story of the Bavarian colonel who was carted about for hours in the belly of one of them like Jonah in the whale, while his captors slew the men of his broken division.

It is too soon yet to advertise their best points to an interested world. The entire army nevertheless is talking about them, and you might imagine that yesterday's operation was altogether a battle of armed chauffeurs if you listened to the stories of some of the spectators. They inspired confidence and laughter. No other incident of the war has created such amusement in the face of death as their debut before the trenches of Martinpuich and Flers. Their quaintness and seeming air of profound intelligence commended them to a critical audience. It was as though one of Mr. Heath Robinson's jokes had been utilised for a deadly purpose, and one laughed even before the dire effect on the enemy was observed.

Flers fell into British hands comparatively easily. The troops sent against it from the north of Delville Wood, astride of the sunken road leading to its southern extremity, reached the place in three easy laps supported by armoured cars. As a preliminary measure one car planted itself at the north-east corner of the wood before dawn and cleared a small enemy party from two connected trenches. It was not a difficult task for the "boches" promptly surrendered. The first halting-place of the Flers-bound troops was a German switch-trench north-east of Ginchy, part of the so-called third line, which they reached at the time appointed. There was a slight obstacle in the form of a redoubt constructed at the angle of the line where it crossed the Ginchy-Lesboeufs road. Machine-gun fire was well directed from this work, but two armoured cars came up and poured a destructive counter-fire into it, and then one of the many watchful aeroplanes swooped down almost within hailing distance and joined in the battle. The dismayed Bavarians promptly yielded to this strange alliance. Armoured cars and aeroplane went their several ways and the infantry carried on. The redoubt sheltered a dressing station where there were a number of German wounded. The second phase of the Flers advance brought the attackers to the trenches at the end of the village. Little resistance was offered. Here, again, the armoured cars came forward. One of them managed to enfilade the trench both ways, killing nearly everyone in it, and then another car started up the main street, or what was the main street in pre-war days, escorted, as one spectator puts it "by the cheering British army."

It was a magnificent progress. You must imagine this unimaginable engine stalking majestically amid the ruins followed by the men in khaki, drawing the dispossessed Bavarians from their holes in the ground like a magnet and bringing them blinking into the sunlight to stare at their captors, who laughed instead of killing them. Picture its passage from one end of the ruins of Flers to the other, leaving infantry swarming through the dug-outs behind, on out of the northern end of the village, past more odds and ends of defensive positions, up the road to Gneudecourt, halting only at the outskirts. Before turning back it silenced a battery and a half of artillery, captured the gunners, and handed them over to the infantry. Finally, it retraced its foot-steps with equal composure to the old British line at the close of a profitable day. The German officers taken in Flers have not yet assimilated the scene of their capture, the crowded "High Street," and the cheering bomb-throwers marching behind the travelling fort, which displayed on one armoured side the startling placard, "Great Hun Defeat. Extra Special!"

(22) In his pamphlet, The Battle of the Somme: The Second Phase, published in 1917, John Buchan claimed that the battle marked the end of "trench fighting and the beginning of a campaign in the open."

Thenceforth, the campaign entered upon a new stage, and the first stage, which in strict terms we call the Battle of the Somme, had ended in Allied victory. We did what we set out to do; step by step we drove our way through the German defences. Our major purpose was attained. It was not the recapture of territory that we sought, but the weakening of the numbers, materiel and moral of the enemy.

(23) In his book, Traveller in News, William Beach Thomas wrote about his reporting of the Battle of the Somme for the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror.

A great part of the information supplied to us by (British Army Intelligence) was utterly wrong and misleading. The dispatches were largely untrue so far as they deal with concrete results. For myself, on the next day and yet more on the day after that, I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written, for the very good reason that it was untrue. Almost all the official information was wrong. The vulgarity of enormous headlines and the enormity of one's own name did not lessen the shame.

(24) John Raws was killed at the Battle of the Somme. He wrote a letter to his brother just before he died (12th August 1916)

The glories of the Great Push are great, but the horrors are greater. With all I'd heard by word of mouth, with all I had imagined in my mind, I yet never conceived that war could be so dreadful. The carnage in our little sector was as bad, or worse, than that of Verdun, and yet I never saw a body buried in ten days. And when I came on the scene the whole place, trenches and all, was spread with dead. We had neither time nor space for burials, and the wounded could not be got away. They stayed with us and died, pitifully, with us, and then they rotted. The stench of the battlefield spread for miles around. And the sight of the limbs, the mangled bodies, and stray heads.

We lived with all this for eleven days, ate and drank and fought amid it; but no, we did not sleep. Sometimes, we just fell down and became unconscious. You could not call it sleep.

The men who say they believe in war should be hung. And the men who won't come out and help us, now we're in it, are not fit for words. Had we more reinforcements up there many brave men now dead, men who stuck it and stuck it and stuck it till they died, would be alive today. Do you know that I saw with my own eyes a score of men go raving mad! I met three in 'No Man's Land' one night. Of course, we had a bad patch. But it is sad to think that one has to go back to it, and back to it, and back to it, until one is hit.

(25) Charles Hudson, journal entry on the Somme offensive in 1916, quoted in Soldier, Poet, Rebel (2007)

Elaborate and very detailed orders for the coming battle came out, and were altered and revised again and again. Inspections and addresses followed each other in rapid succession whenever we came out of the line. The country, miles ahead of our starting trench, was studied on maps and models. Mouquet Farm, the objective of my company on the first day, will always stand out in my memory as a name, though I was never to see it.

Our battalion was to be the last of the four battalions of our Brigade to go 'over the top'. We were to carry immense loads of stores needed by the leading battalion, when the forward enemy trench system was overrun, and dump our loads before we advanced on Mouquet Farm. In the opening phase therefore, we were reduced to the status of pack mules. We flattered ourselves however that we had been specially selected to carry out the more highly skilled and onerous role of open warfare fighting, when the trench system had been overcome.

Never in history, we were told, had so many guns been concentrated on any front. Our batteries had the greatest difficulty in finding gun positions, and millions of shells were dumped at the gun sites. Had all the guns, we were told, been placed on one continuous line, their wheels would have interlocked. Nothing, we were assured, could live to resist our onslaught.

The first unpleasant hitch in the arrangements occurred when the attack was put off for twenty-four hours. It was later postponed another twenty-four hours. The explanation given was that the French were not ready. Our own non-stop night and day bombardment continued. We were in the front line, with the assaulting battalions behind us in reserve trenches. Apart from the strain of waiting, we found our own shelling exhausting, and received a fair amount counter-shelling and mortaring in reply. We remained in the front line from 27 June until the night of 30 June, when we were withdrawn to allow the assaulting units to take up their positions. As a result of the forty-eight hour postponement the men were not as fresh for the attack as we had hoped, and there was a feeling abroad that a lot of ammunition had been expended which might be badly missed later.

That night, 30 June, we spent in dugouts cut into the side of a high bank. Behind us lay the shell-shattered remains of Authuile Wood, and further back the town of Albert. That night I was asked to attend a party given by the officers of another company. Reluctantly I went. Though no one in the smoke-filled dugout when I arrived was drunk, they were far from being sober and obviously strung up. Their efforts to produce a cheerful atmosphere depressed me. Feeling a wet blanket, I slipped away as soon as I decently could. As I walked back, the gaunt misshapen shell-shattered trees looked like grim tortured El Greco-like figures in the moonlight. I tried to shake off emotion, and though feeling impelled to pray, I deliberately refused myself the outlet, for to do so now, merely because I was frightened, seemed both unfair and unreasonable. Fortunately I could always sleep when the opportunity arose, and I slept normally well that night.

Though my company was not due to move up the communication trench until some time after zero hour, breakfasts were over and the men were all standing by before it was light. At dawn the huge, unbelievably huge, crescendo of the opening barrage began. Thousands and thousands of small calibre shells seemed to be whistling close above our heads to burst on the enemy front line. Larger calibre shells whined their way to seek out targets farther back, and shells from the heavies, like rumbling railway trains, could be heard almost rambling along high above us, to land with mighty detonations way back amongst the enemy strong-points and battery areas behind.

It was not long before the electrifying news came down the line that our assault battalions had overrun the enemy front line and had been seen still going strong close up behind the barrage. The men cheered up. The march to Berlin had begun! I was standing on the top of the bank, and at that moment I felt genuinely sorry for the unfortunate German infantry. I could picture in my mind the agony they were undergoing, for I could see the solid line of bursting shells throwing great clouds of earth high into the air. I thought of the horror of being in the midst of that great belt of explosion. where nothing. I thought, could live. The belt was so thick and deep that the wounded would be hit again and again.

Still there was no reply from the enemy. It looked as if our guns had silenced their batteries before they had got a shot off. I climbed down the bank anxious for more news. When our time came to advance we had to file some way along and under the embankment before turning up the communication trench. A company of the support battalion was to precede us and their men were already on the move gaily cracking ribald jokes as they passed by.

They had not long been gone when the enemy guns opened. This in itself was rather startling. How. I wondered, could any guns have survived? Only a few odd shells fell near us but the shelling farther up seemed very heavy. We were not, then, going to have it all our own way. Impatient, I slipped on ahead of the company to the entrance of the communication trench up which we were to go.

Some wounded were already being carried out and I wondered whether the stretchers would delay our advance. As I neared the trench, I saw the Brigade trench mortar officer, and went to get the latest news from him. To my disgust I found he was not only very drunk but in a terrible state of nerves. With tears running down his face, and smelling powerfully of brandy, he begged me not to take my company forward. The whole attack he shouted was a terrible failure, the trench ahead was a shambles, it was murder up there, he was on his way to tell the Brigadier so...

We found the short length of trench packed tight with wounded. Some begged for help, some to be left alone to die. I told the company sergeant major (CSM) to set about clearing the trench of wounded while I went to tell platoon commanders the alteration in our plan. When I got back the CSM was bending over a severely wounded young officer. He was very heavy and when an attempt was made to move him the pain was so acute that the men making the attempt drew back aghast. The trench was very narrow and as he lay full-length along it we had to move him. As long as I live I shall not forget the horror of lifting that poor boy. He died, a twitching mass of tautened muscles in our arms as we were carrying him. Even my own men looked at me as if I had been the monster I felt myself to be in attempting to move him. Sick with horror, I drove them on, forcing them to throw the dead bodies out of the trench.

At last the way was clear, and I called up the first platoon to go over the narrow end of the trench, two at a time. I was to go first with my two orderlies, and Bartlett, the officer commanding the first platoon, was to follow. I told the CSM to wait and see the company over but he flatly declined, saying his place was with company HO and that he was coming with me. I hadn't the heart to refuse him.

As I ran, wisps of dust seemed to be spitting up all round me, and I found myself trying to skip over them. Then it suddenly dawned on me that we were under fire, and the dust was caused by bullets. I saw someone standing up behind the bank ahead waving wildly. He was shouting something. I threw myself down. It was the second-in-command of the support battalion, an ex-regular regimental sergeant major of the Guards and a huge man. He was shouting. "Keep away, for God's sake, keep away!"

I shouted back, "What's up?"

"We are under fire here," he yelled, "You'll only draw more fire."

I realised that the fire came not only from in front of us but from across the valley to our left and behind us. My plan was hopeless. The young orderly who had had hysterics was hit. He cried out and was almost immediately hit again. I crept close up against his dead body, wondering if a man's body gave any protection. Would that machine gunner never stop blazing at us? In an extremity of fear I pulled a derelict trench mortar barrel between me and the bullets. Suddenly the fire was switched off to some other target.

The CSM had been hit as he had been crawling towards me. I had shouted to him to keep down but he crawled on, his nose close to the ground, his immense behind clearly visible, and a tempting target! It is extraordinary how in action one can be one moment almost gibbering with fright, and the next, when released from immediate physical danger, almost gay. When the CSM let out a loud yell, I shouted: "Are you hit"

"Yes, Sir," he shouted back. "But not badly."

"That will teach you to keep your bottom down," I shouted back, upon which there was a ribald cheer from the men nearby. When I reached the CSM he was quite cheerful and wanted to carry on, but was soon persuaded to return and stop more men leaving the trench.

Bartlett had taken cover in a shell hole and I rolled in to join him as the firing swept over us again. Besides us, the hole was occupied by an elderly private of one of the leading battalions. He was unwounded, quite resigned, and entirely philosophic about the situation. He said no one but a fool would attempt to go forward, as it was obvious that the attack had failed. He pointed out that we were quite safe where we were, and all we had to do was to wait until dark to get back. I asked him what he was doing unwounded in a hole so far behind his battalion. He said he was a regular soldier who had been wounded early in the war, and that he was not going to be wounded again in the sort of fool attacks that the officers sitting in comfortable offices behind the lines planned! (I give of course a paraphrase of his actual discourse.) He said he certainly would not be alive now if he had not had the sense to take cover as soon as possible after going over the top, as he had done at Festubert. Loos, and a series of other battles in which he said he had been engaged. He reckoned that this was the only hope an infantryman had of surviving the war. When the High Command had learned how to conduct a battle which had a reasonable chance of success, he would willingly take part! I told him if he went on in this way, I would put him under arrest for cowardice.

It was a strange interlude in battle, and I realised that my own uncertainty as to what should be done gave rise to it. I was agitated, feeling that inactivity was unforgivable, particularly when the leading battalions must be fighting for their lives, and sorely needing reinforcements. It seemed Useless to attempt to get forward from where we were, even if we could collect enough men to make the attempt. In the end I forced myself to get out of the shell hole and walk along parallel with the enemy line and away from the valley on our left, calling on men of all battalions who were scattered about in shell holes, to be ready to advance when I blew mv whistle.

This effort, in which I was supported by Bartlett, was shortlived. Bullets were flying all round us both from front and flank. One hit my revolver out of my hand, another drove a hole through my water bottle, and more and more fire was being concentrated upon us. Ignominiously I threw myself down. We were no better off.

It was up to me to make a decision. Bartlett quietly but firmly refused to offer any suggestion. I took the only course that seemed open to me, other than giving in altogether as the defeatist private soldier had so phlegmatically advocated, and I so vehemently condemned. We returned to our own front line, crawling all the way and calling on any men we saw to follow us, though few in fact did.

There was no movement in no man's land, though one apparently cheerful man of my own company, a wag, was crawling forward on all fours, a belt of machine gun ammunition swinging under his stomach, shouting. Anyone know the way to Mouquet Farm?

A soldier I did not know was running back screaming at the top of his voice. He was entirely naked and had presumably gone mad, or perhaps he thought he was so clearly disarmed that he would not be shot at! Bartlett and I reached our trench without mishap and began working down it, trying to collect any men we could. The shelling on the front line trench had stopped. At one trench shelter I came on a sergeant who had once been in my company, and at my summons he lurched to the narrow entrance of the tiny shelter. I thought at first he was drunk.

"Come on, Sergeant," I said, "Get your men together and follow me down the trench."

"I'd like to come with you, Sir," he said, "But I can't with this lot."

I looked down and saw to my horror that the lower part of his left leg had been practically severed. He was standing on one leg, holding himself upright by gripping the frame of the entrance.

At the junction of the front line with a communication trench further down the line, I found the staff captain (not the one with the broken nerves). I told him I was collecting the remnants of our men, and asked him if he thought I ought to make another effort to advance. I knew in my heart that I only asked because I hoped he would authorise no further effort, but he said that the last message he had had from Brigade HO was that attempts to break through to the leading battalions must continue to be made at all costs. He told me our colonel and second-in-command had gone over the top to try and carry the men forward, and both had been wounded. I must judge for myself, he said, but there had been no orders to abandon the attack.

I discovered from the staff captain what had happened. The leading battalions had swept over the enemy trenches without opposition, but had not delayed to search the deep dugouts, as this was the job of the supporting battalion. As the supporting battalion had been held up by shellfire, the German machine gunners in the deep dugouts had had time to emerge from their cover and open fire. It seemed clear that, unpleasant as the prospect was, a further effort to advance must be made. There was a slight depression in no man's land further to the right, which would give a narrow column of men, crawling, cover from fire from both flanks and front. I determined to try this, and the staff captain wished me luck.

Bartlett had by now collected about forty men, and standing on the fire step, I told them what had happened. There could not be many enemy in the front line, I said. If we could once penetrate into the enemy trench it would not be difficult to bomb our way along it; then we could call forward many of our own men who were pinned to the ground in no man's land. I painted a very rosy picture. One more effort and victory was ours. Hundreds of battles had. I said, been lost for the lack of that one last effort.

We had got a good many men over the parapet when a machine gun opened up. I do not think the fire was actually directed at us but I was just giving a man a hand up when a bullet went straight through the lobe of his ear, splashing blood over both of us. The men in the trench below were very shaken, though not more than I was! The man hit wasted no time in diving into cover, but there was nothing I could do except stay where I was, as the men would never have come on if I were to disappear into the cover I was longing to take. Luckily the enemy machine gunner did not swing his gun back as I had feared.

When all the men were over the parapet, Bartlett and I started to crawl past them up to the top of the column. Not a shot was being fired at us and I told Bartlett to pass the men as they came up, down a line parallel to the enemy trench, while I crawled on a bit to see if the wire opposite us was destroyed. I heard a few enemy talking well away to our left, a machine gun opened up, but it was firing away from us. The wire seemed fairly well destroyed. I slipped back to Bartlett to find that only eight men had reached him, and that no one else seemed to be coming. Eight men were enough to surprise and capture the machine gun or never. I jumped up and feeling rather absurdly dramatic, I ran along our short line of men shouting "Charge!" Bartlett was at my heels and as I turned towards the enemy line some men rose to their feet.

I remember trying to jump some twisted wire, being tripped up and falling headlong into a deep shell hole right on top of a dead man and an astonished corporal. Soon a shower of hand bombs were bursting all round us and the corporal and myself pressed ourselves into the side of the shell hole. When I had recovered my breath I shouted for Bartlett and was relieved to hear a muffled reply from a nearby shell hole.

It was now about eleven o'clock on a very hot day. Bartlett and I managed to dig our way towards each other with bayonets, but we failed to get in touch with any of our men, who had apparently not come as far. The corporal turned out to be badly wounded and in spite of our efforts to help him his pain increased as the day wore on. Whenever we showed any sign of life the enemy lobbed a bomb at us and we soon learned to keep quiet.

That night, except for an occasional flare and a little desultory shelling, was absolutely quiet. In the light of a flare it seemed as if the whole of no man's land was one moving mass of men crawling and dragging themselves or their wounded comrades back to our trenches. Bartlett and I tried to carry the corporal but he was very heavy and in such pain that he begged me to be put down at frequent intervals. There were some stretcher bearers about and I sent Bartlett to find one but he lost his way and I did not see him again until next day.

In the end I crawled under the corporal and managed to get him onto my shoulders. He died in my arms soon after we reached our own front line.

(26) In his autobiography, My War Memories, 1914-1918, Eric Ludendorff wrote about the impact of the Battle of the Somme.

On the Somme the enemy's powerful artillery, assisted by excellent aeroplane observation and fed with enormous supplies of ammunition, had kept down our own fire and destroyed our artillery. The defence of our Infantry had become so flabby that the massed attacks of the enemy always succeeded. Not only did our moral

suffer, but in addition to fearful wastage in killed and wounded, we lost a large number of prisoners and much material.

The most pressing demands of our officers were for an increase of artillery, ammunition, aircraft and balloons, as well as larger and more punctual allotments of fresh divisions and other troops to make possible a better system of reliefs.

The equipment of the Entente armies with war material had been carried out on a scale hitherto unknown. The Battle of the Somme showed us every day how great was the advantage of the enemy in this respect.

When we added to this the hatred and immense determination of the Entente, their starvation-blockade or stranglehold, and their mischievous and lying propaganda, which was so dangerous for us, it was quite obvious that our victory was inconceivable unless Germany and her Allies threw into the scale everything they had, both in manpower and industrial resources, and unless every man who went to the front took with him from home a resolute faith in victory and an unshakable conviction that the German Army must conquer for the sake of the Fatherland. The soldier on the battlefield, who endures the most terrible strain that any man can undergo, stands, in his hour of need, in dire want of this moral reinforcement from home, to enable him to stand firm and hold out at the front.

(27) After the war General Sixt von Armin wrote about what the German Army learnt from the Battle of the Somme.

One of the most important lessons drawn from the Battle of the Somme is that, under heavy, methodical artillery fire, the front line should be only thinly held, but by reliable men and a few machine guns, even when there is always a possibility of a hostile attack. When this was not done, the casualties were so great before the enemy's attack was launched, that the possibility of the front line repulsing the attack by its own unaided efforts was very doubtful. The danger of the front line being rushed when so lightly held must be overcome by placing supports (infantry and machine guns), distributed in groups according to the ground, as close as possible behind the foremost fighting line. Their task is to rush forward to reinforce the front line at the moment the enemy attacks, without waiting for orders from the rear. In all cases where this procedure was adopted, we succeeded in repulsing and inflicting very heavy losses on the enemy, who imagined that he had merely to drop into a trench filled with dead.

(28) Duff Cooper was asked by the Haig family to write Sir Douglas Haig's official biography. The book included an evaluation of Haig's tactics at the Battle of the Somme.

There are still those who argue that the Battle of the Somme should never have been fought and that the gains were not commensurate with the sacrifice. There exists no yardstick for the measurement of such events, there are no returns to prove whether life has been sold at its market value. There are some who from their manner of reasoning would appear to believe that no battle is worth fighting unless it produces an immediately decisive result which is as foolish as it would be to argue that in a prize fight no blow is worth delivering save the one that knocks the opponent out. As to whether it were wise or foolish to give battle on the Somme on the first of July, 1916, there can surely be only one opinion. To have refused to fight then and there would have meant the abandonment of Verdun to its fate and the breakdown of the co-operation with the French.

(29) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

We receive orders to go into the line on the right of the British Army, near the River Somme. The great battle of 1916 has died down. It is November. The weather has brought the fight to a standstill. `General Winter' is in command. We occupy a line recently taken over from the French. In reality there is no line in the trench sense. The men occupy - hellholes. Six entire villages in the neighbourhood have been destroyed by the shells of both sides. Only a little red rubble remains, and that is mostly brick mud. It freezes hard, then it thaws. Never was there a winter such as the men endured in 1916 and 1917. The last was bad enough; this is worse, as accommodation in the line does not exist. Dugouts and communication trenches cannot be constructed during a battle; after, it is too late, as the mud and rain prevent the carrying up of material. Latrines there are none. The sanitary arrangements are entirely haphazard and makeshift. Disinfectants help.

We at brigade are comfortable - the French have seen to that. Otherwise the conditions are appalling. The condition known as trench feet is our bugbear; but the measures taken last year, if properly carried out, suffice to combat the evil. One battalion, through neglect, loses over a hundred men in four days from this malady. The colonel is at fault, and goes away. This example improves matters.

Little can be done, except keep the sick rate down during the next three trying months. How the men live I do not know. They cannot be reached by day as there are no trenches. Cover there is none. Once this place was a field of corn, now it is a sea of mud. On it the French fought a desperate battle, earlier in the year. My daily route on a duckboard track lies through the Rancourt valley. I count a hundred and two unburied Frenchmen, lying as they fell, to the left of me; while opposite there are the corpses of fifty-five German machine-gunners by their guns, the cartridge belts and boxes still being in position. Viewed from the technical and tactical point of view their dead bodies and the machine guns afford a first-rate exposition of modern tactics. Later, when the ground hardens, and we can walk about without fear of drowning or being engulfed, I take officers over the battlefield and point out the lessons to be learnt, having in view the positions of the dead bodies. The stench is awful; but then, and only then, are we able to get at the dead for burial. If the times are hard for human beings, on account of the mud and misery which they endure with astounding fortitude, the same may be said of the animals. My heart bleeds for the horses and mules. We are in the wilderness, miles from towns and theatres, the flood of battle having parched the hills and dales of Picardy in its advance against civilization. Like all other floods, it carries disaster in its track, with this addition, being man-made, and ill-founded, as it is, in its primary inception, it lacks the lustre of God-inspired help. God is wrongly claimed as an ally, by both parties, to the detriment of the other; whereas the Almighty, benevolent and magnanimous, watches over all and waits the call to enter - but not as a destroyer.

The men in muddy hell need daily supplies. The conditions are so vile that no man can endure more than forty-eight hours at a stretch in the forward puddles and squelch pits. Do those at home in comfort, warmth, and cultured environment realise what they owe to the stout hearts on the western front? No wheeled traffic can approach within three miles of the forward pits; for roads which were useful to the pre-war farmers have now disappeared. Everything must be carried up by men or mules. The latter, stripped of harness, or fully dressed, die nightly in the holes and craters, as they bring their loads to the men they serve so faithfully and well, urged on by whips and kindness. But one false step means death by suffocation. Sheer exhaustion claims its quota, for the transport lines themselves are devoid of cover from wind and rain. Such is the animals' war, and could animal lovers see the distress of their dumb friends they would never permit another conflict.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)