Classroom Activity on Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer

Walter Tull, the son of Daniel Tull, was born at 57 Walton Road, Folkestone, on 28th April 1888. Walter's father, the son of a slave, had arrived from Barbados in 1876 and had found work as a carpenter.

Daniel Tull married Alice Elizabeth Palmer, a young woman from Hougham. Over the next few years the couple had six children. In 1895, when Walter Tull was seven, his mother died of cancer. A year later his father married Alice's cousin, Clara Palmer. She gave birth to a daughter Miriam, on 11th September 1897. Three months later Daniel died from heart disease.

The stepmother was unable to cope with so many children. The resident minister of Grace Hill Wesleyan Chapel, recommended that two boys of school-age, Walter and Edward, should be sent to the Children's Home and Orphanage (CHO) in Bethnal Green. Edward and Walter Tull lived in the orphanage for the next two years. Clara Tull did have the right to claim the boys back. However, if she did, she had to pay eight shillings per week times the length of duration in the orphanage would have to be repaid. This meant it was virtually impossible to raise the money needed to reclaim her children.

Primary Sources

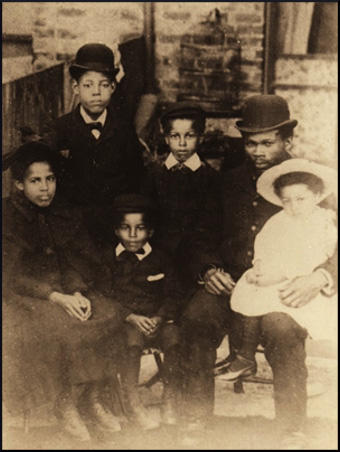

and his brother Edward is next to his father (c. 1896).

(Source 2) Phil Vasili, Colouring Over the White Line (2000)

Placing the two school-age boys in the home, it was hoped, would prevent the family becoming destitute. The eldest son William was working, and could therefore make his weekly contribution to the family pot, while Alice's two girls - Cecilia, 13 and Elsie, 6 - could help Clara with baby Miriam and the domestic chores. In this set-up, Edward and Walter were liabilities: extra mouths to feed and bodies to clothe...

At the CHO he would have been trained into the Methodist ethos of Muscular Christianity - playing games to develop a fit body and compliant attitude of mind - a doctrine that inferred that being paid to play any sport misses the point of what playing is all about. Muscular Christianity, for the Methodists, was about character building. To play football for wages would change the nature of the game and its players, making profit/winning the ultimate objective rather than the development of a moral character.

(Source 4) The Daily Chronicle (9th October, 1909)

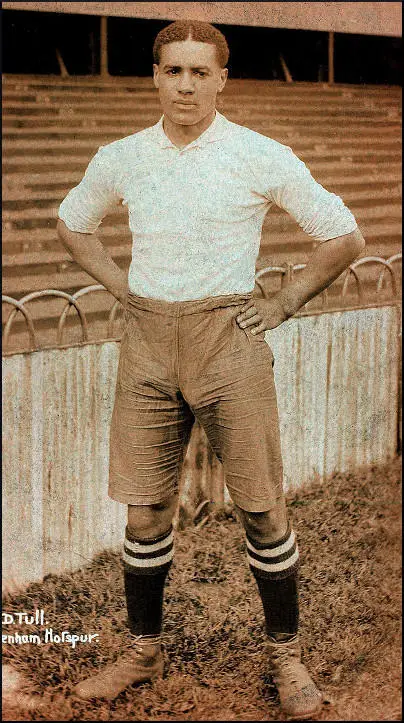

Tull's... display on Saturday must have astounded everyone who saw it. Such perfect coolness, such judicious waiting for a fraction of a second in order to get a pass in not before a defender has worked to a false position, and such accuracy of strength in passing I have not seen for a long time. During the first half, Tull just compelled Curtis to play a good game, for the outside-right was plied with a series of passes that made it almost impossible for him to do anything other than well.

Tull has been charged with being slow, but there never was a footballer yet who was really great and always appeared to be in a hurry. Tull did not get the ball and rush on into trouble. He let his opponents do the rushing, and defeated them by side touches and side-steps worthy of a professional boxer. Tull is very good indeed.

(Source 6) Newspaper report on the game between Tottenham Hotspur and Bristol City (October, 1909)

A section of the spectators made a cowardly attack upon him (Walter Tull) in language lower than Billingsgate...Let me tell these Bristol hooligans (there were but few of them in a crowd of nearly twenty thousand) that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football whether they be amateur or professional. In point of ability, if not in actual achievement, Tull was the best forward on the field.

(Source 8) Stephen Studd, Herbert Chapman: Football Emperor (1981)

Meetings were held each week to discuss both the previous game and the tactics to be used in the next. With Chapman presiding, every player was encouraged to express his own opinion. This was something entirely new in football, a marked contrast to the prevailing easy-going system where players were left to work out their own tactics. In holding the talks Chapman was asking his players to contribute to a joint effort, to become more involved with each other as a unit. It was an appeal to intelligence as well as physical skill, and it had the effect of boosting self-respect, fostering a sense of loyalty, and raising a player's status above that of a mere paid servant.

(Source 9) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1934)

I am always sorry for clubs who have to act hurriedly in seeking a new player, for under the most favourable conditions it is a tricky business and demands the closest consideration. It is not enough that a man should be a good player. There are all sorts of other important factors which have to be taken into account. This takes time. The longer I have been on the managerial side of the game, the more I am convinced that all-round intelligence is one of the highest qualifications of the footballer.

(Source 10) Walter Tull, letter to Edward Tull-Warnock (January 1916)

For the last three weeks my Battalion has been resting some miles distant from the firing line but we are now going up to the trenches for a month or so. Afterwards we shall begin to think about coming home on leave. It is a very monotonous life out here when one is supposed to be resting and most of the boys prefer the excitement of the trenches.

(Source 13) In his book Goodbye to All That, Captain Robert Graves wrote about what happened when a popular officer was wounded in No Mans Land.

Sampson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He was badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts: two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Sampson waved him back, saying he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the company for making such a noise. At dusk we all went out to get the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came across was Sampson. He had been hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death.

(Source 14) Lieutenant Pickard, letter to Edward Tull-Warnock (17th April 1918)

Of course you have already heard of the death of 2nd Lieutenant W. D. Tull on March 25th last.

Being at present in command (the captain was wounded) - allow me to say how popular he was throughout the Battalion. He was brave and conscientious; he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and had certainly earned it, the Commanding Officer had every confidence in him, and he was liked by the men.

Now he has paid the supreme sacrifice; the Battalion and Company have lost a faithful officer; personally I have lost a friend. Can I say more, except that I hope that those who remain may be true and faithful as he.

(Source 15) The Daily Mirror (9th March, 2013)

On the football field, he was a star – on the battlefield, he was a hero....

Now, 95 years after he was killed on the Western Front, a campaign has been launched to preserve the memory of the British Army’s first black officer and one of the country’s first black professional footballers.

To this day, mystery surrounds the fact that Walter was never given a bravery medal, despite a claim that he was recommended for one.

Was it due to the colour of his skin?

It took courage to be a black man in early 20th Century Britain.

Black faces were rare and Walter sometimes ran on to the pitch to face jeering crowds.

All too soon he would need all his courage to lead men into battle.

It is a measure of the devotion Walter’s men held for him that they made repeated attempts to find his body but were driven back by heavy machine-gun fire....

Meanwhile the mystery of why he never received the Military Cross remains. There is no official record that his name was ever put forward, despite the claim by the other officer.

One theory is that promoting a black man to officer was against the rules and it might have been embarrassing for generals to see a gallantry medal pinned to his chest....

An online petition is aiming for 100,000 signatures to urge the Government to take up Walter’s case – and finally award him his Military Cross posthumously.

(Source 16) Phil Vasili, interview, (9th March, 2013)

Walter Tull was made an officer at a time when the Army was desperately short of men of officer material.

I’m convinced that to have given him his Military Cross would have admitted to the powers-that-be at the War Office that rules had been broken in commissioning a black man.

But his promotion illustrated the absurdity of their thinking, that white soldiers would not respect black officers.

(Source 17) The Guardian (3rd September, 2014)

The first black officer in the British Army will be remembered on a special set of coins released by the Royal Mint as part of commemorations of the centenary of the first world war.

Kent-born Walter Tull, who was promoted to officer rank during the war despite a ban on black officers, died in battle in 1918.

Tull was also one of the first black footballers to play at the highest level in the UK, appearing for Tottenham before moving to Northampton Town, where he is commemorated with a statue.

Campaigners, including the former Tottenham player Garth Crooks, petitioned the government last year to posthumously award Tull a Military Cross for his heroism.

He fought on the Somme in 1916 and became the first black combat officer in the British army, despite a military rule excluding “negroes” from exercising actual command. Tull was cited for “gallantry and coolness” for leading his company of 26 men to safety in Italy, but returned to northern France where he was killed in March 1918.

The coin, featuring a portrait of the officer with a backdrop of infantry soldiers going “over the top”, will be one of a set of six £5 coins to remember the sacrifice made by so many during the war.

Questions for Students

Question 1: Read the introduction and study sources 1 and 2. Why were Walter and Edward Tull sent to the Children's Home and Orphanage (CHO) in Bethnal Green in 1898? Why was it unlikely that the boys had little hope of returning home until they were old enough to go to work?

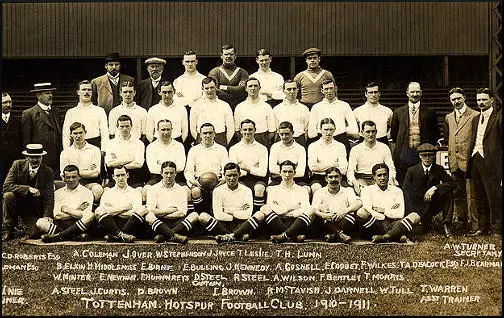

Question 2: What do sources 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 tell us about Walter Tull's football career?

Question 3: Herbert Chapman signed Walter Tull to play for Northampton Town in 1911. Read sources 8 and 9 and explain what Chapman was looking for when he signed a player.

Question 4: Read source 10. What was Walter Tull's problem in January 1916? Do you think it remained his main problem over the next few weeks?

Question 5: Walter Tull was hit by machine-gun fire in No Mans Land on 25th March, 1918. Several men attempted to bring him back to British lines. Read sources 13 and 14 and explain what this tell us about 2nd Lieutenant Tull's relationship with his men?

Question 6: Study sources 11 and 12. How do these sources support one of the statements made in source 15.

Question 7: Lieutenant Pickard in source 14 says Walter Tull was recommended for the Military Cross. Read source 16 and explain why Phil Vasili thinks he was not awarded this medal. Can you give any other reasons why he did not receive the medal?

Question 8. Read sources 15 and 17. What do you think is the best way to make sure we do not forget Walter Tull?

Answer Commentary

A commentary on these questions can be found here

Download Activity

You can download this activity in a word document here

You can download the answers in a word document here