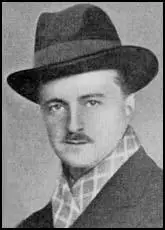

Duff Cooper

Duff Cooper was born on 22nd February, 1890. After being educated at Eton and New College, Oxford, he joined the Foreign Office.

During the First World War Cooper joined the British Army and as a Second Lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards, was sent to the Western Front in France in April 1917.

A member of the Conservative Party, Cooper was elected to the House of Commons in October 1924. He represented Oldham until being defeated in the 1929 General Election. He returned to Parliament two years later when he won at the St. George's division of Westminister.

Ramsay MacDonald appointed Cooper as Financial Secretary to the War Office in August 1931. This was followed by posts as Financial Secretary to the Treasury to the Treasury (June, 1934 - November, 1935) and Secretary of State for War (November, 1935 - May, 1937).

Cooper and was appointed as First Lord of the Admiralty in May, 1937. Cooper disagreed with the appeasement policy of Neville Chamberlain and resigned from office after the signing of the Munich Agreement.

When Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940, he appointed Cooper as Minister of Information. He also served as Chancellor of Duchy of Lancaster (July 1941 - November 1943).

Cooper retired from the House of Commons in 1945 and became the Ambassador in Paris. He was created Viscount Norwich in 1952 and his autobiography, Old Men Forget, was published the following year. Duff Cooper died on 1st January, 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) Duff Copper, letter to his parents (22nd May, 1918)

As we got nearer the battle and the guns became louder my horse grew rather nervous and began shying at each shell-hole and I was terrified of falling off. At last we got off and left them with two grooms. We then had a few hundred yards to walk to the Battalion Headquarters. There we descended into the bowels or into one bowel of the earth, an incredibly deep dug-out with rather uneven steps down into it, which I thought most unsafe. At the bottom we found Harry Lascelles, who is Second in Command of this Battalion. He was looking extraordinarily elegant, and beautifully clean. I felt ashamed to be covered with perspiration, very untidy and wearing camouflage - i.e. a private's uniform. There was another elegant young man with him called Fitzgerald and the table was strewn with papers and periodicals like Country Life and the Burlington Magazine, which one associates with the comfortable houses of the rich.

I was led by a guide to my own Company, twenty minutes' walk over green fields, while the sun was beginning to set most beautifully. At last we arrived at a dugout, an ordinary shallow one, and here I met my captain face to face - nobody more surprised than my captain, as he had expected someone else of the same name. It was then 8.15. He called for dinner for two, which was immediately produced. Quite good soup, hot fish tasting like sardines but larger - no one knew what they were - old beef, pickles and peas, prunes and custard - plenty of whisky and port. It was still light when we finished and I was sent on to the very front line of all, in order that the officer there might come back and dine. The front proved extraordinarily unalarming - and it was rather thrilling to think that there was nothing between oneself and the German Army.

(2) Duff Copper, took part in his first attack on the German trenches on 20th August, 1918.

I pressed on alone with my platoon guiding myself roughly by the sound of our guns behind us. We were occasionally held up by machine-gun fire and we met one or two stray parties of Scots Guards without officers. Finally we met a fairly large party of the Shropshires, who I knew should be on our right. The officer with them did not know where he was, but we agreed to go on together.

We ran into a small party of the enemy, of whom we shot six and took two prisoners, including an officer. We then learnt that we were on the outskirts of Courcelles. We had gone a great deal too far to the right. I tried to get back by going up a road to the left but could not get on owing to a machine-gun firing straight down the road. There were several dead men lying about this road, one particularly unpleasant one with his face shot away. These were the first sights of the kind I had seen and I was glad to find that they did not affect me at all. I had often feared that they might have some physical effect on me, as in ordinary life I hate and always avoid disgusting sights.

I went back to the beginning of the road, where I found a tank which, like everyone else, had lost its way in the mist. It consented to go up the road in front of us, and we were not troubled further by the machine-gun. I got on to another road which led straight up to the Halte on the Arras-Albert railway. This was the right of the final objective of my Company. There was a ruined building there from which a few shots were fired. We lay down and returned their fire with rifles and Lewis guns. Six Germans ran out with their hands up. We took them prisoner. Almost at the same time a party of the Shropshires came round on the left of the building. There was a steep bank on the edge of the railway, along which I told my men to dig themselves fire-positions

So we obtained our objective. Not only were we the first to do so but we were the only platoon in the Company who succeeded in doing so at all. I sent a report to the Commanding Officer and later in the day I got his reply - only two words - "Well done."

It was then 9 a.m. Not long afterwards I saw No. 1 Company coming over the hill behind us. Fryer came on to see me. We heard that No 2 Company, which had come through No. 4, as No. 1 had through No. 3, was on our left, but there was a considerable gap between. Fryer and I started walking down the edge of the railway embankment towards No. 2. Suddenly we noticed an enemy machine-gun shooting through the hedge along which we were walking. It was just in front of us and we had almost walked into it. We hurried back and on the way were fired at by machine-guns from the other side of the railway cutting. Fryer told me to take a Lewis gun and a couple of sections and capture or knock out the machine-gun. It was rather an alarming thing to be told to do.

However, I got my Lewis gun up to within about eighty yards of it, creeping along the hedge. The Lewis gun fired away. When it stopped I rushed forward. Looking back I saw that I was not being followed. I learnt afterwards that the first two men behind me had been wounded and the third killed. The rest had not come on. One or two machine-guns from the other side of the railway were firing at us. I dropped a few yards away from the gun I was going for and crawled up to it. At first I saw no one there. Looking down I saw one man running away up the other side of the cutting. I had a shot at him with my revolver. Presently I saw two men moving cautiously below me. I called to them in what German I could at the moment remember to surrender and throw up their hands. They did so immediately. They obviously did not realise that I was alone. They came up the cutting with their hands up, followed, to my surprise, by others. There were eighteen or nineteen in all. If they had rushed me then they would have been perfectly safe, for I can never hit a haystack with a revolver and my own men were eighty yards away.

(3) Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953)

I acquired little credit during my tenure of the War Office. With the means at my disposal there was not much to be done. Chamberlain knew that he could not save money on the Navy or the Air Force, therefore the Army offered the only hope of economizing. A distinguished General, whom he had met fishing, had implanted in his mind the pernicious doctrine that if we contributed to the cause the greatest Navy in the world and a first-rate Air Force, our allies could hardly expect more. His aim, as his biographer Mr. Keith Feiling has told us, was an army of four divisions and one mechanised division, and he held that the dudes of the Territorial Army should be confined to anti-aircraft defence. He also believed firmly "that war was neither imminent nor inevitable, that we could build on some civilian elements, such as the instability of German finance, which made it less likely."

(4) Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953)

I had been glad when Eden had become Foreign Secretary and I had always given him my support in Cabinet when he needed it. I believed that he was fundamentally right on all the main problems of foreign policy, that he fully understood how serious was the German menace and how hopeless the policy of appeasement. Not being, however, a member of the Foreign Policy Committee, I was ignorant of how deep the cleavage of opinion between him and the Prime Minister had become. It is much to his credit that he abstained from all lobbying of opinion and sought to gain no adherents either in the Cabinet or the House of Commons.

Had he made an effort to win my support at the time he would probably have succeeded, but with regard to Italy I held strong opinions of my own. I felt, as I have written earlier, that the Abyssinian business had been badly bungled, that we should never have driven Mussolini into the arms of Hitler, and that it might not be too late to regain him. The Italo-German alliance was an anomaly. The Germans and Austrians were the traditional enemies of the Italians; the English and the French, who had contributed so much to their liberation, were their historic friends, and Garibaldi had laid a curse upon any Italian Government that fought against them. The size and strength of the Third Reich made her too formidable a friend for the smallest of the Great Powers, who would soon find that from an ally she had sunk to a satellite. These were the thoughts that were in my mind during the long Cabinet meeting that took place that Saturday afternoon.

(5) Duff Cooper, diary entry (17th September, 1938)

At the Cabinet meeting Runciman was present and described his experiences in Czechoslovakia. It was interesting, of course, but quite unhelpful, as he was unable to suggest any plan or policy.

The Prime Minister then then told us the story of his visit to Berchtesgaden. Looking back upon what he said, the curious thing seems to me now to have been that he recounted his experiences with some satisfaction. Although he said that at first sight Hitler struck him as "the commonest little dog" he had ever seen, without one sign of distinction, nevertheless he was obviously pleased at the reports he had subsequently received of the good impression that he himself had made. He told us with obvious satisfaction how Hitler had said to someone that he had felt that he, Chamberlain, was "a man."

But the bare facts of the interview were frightful. None of the elaborate schemes which had been so carefully worked out, and which the Prime Minister had intended to put forward, had ever been mentioned. He had felt that the atmosphere did not allow of them. After ranting and raving at him, Hitler had talked about self-determination and asked the Prime Minister whether he accepted the principle. The Prime Minister had replied that he must consult his colleagues. From beginning to end Hitler had not shown the slightest sign of yielding on a single point. The Prime Minister seemed to expect us all to accept that principle without further discussion because the time was getting on. The French, we heard, were getting restive. Not a word had been said to them since the Prime Minister left England, and one of the dangers which I had feared seemed to be materialising, namely trouble with the French. I thought we must have further time for discussion and that it would be better to take no decision until discussions with the French had taken place, lest they should be in a position to say that we had sold the pass without ever consulting them

We met again that afternoon. I then argued that the main interest of this country had always been to prevent any one Power from obtaining undue predominance in Europe; but we were now faced with probably the most formidable Power that had ever dominated Europe, and resistance to that Power was quite obviously a British interest. If I thought surrender would bring lasting peace I should be in favour of surrender, but I did not believe there would ever be peace in Europe so long as Nazism ruled in Germany. The next act of aggression might be one that it would be far harder for us to resist. Supposing it was an attack on one of our Colonies. We shouldn't have a friend in Europe to assist us, nor even the sympathy of the United States which we had today. We certainly shouldn't catch up the Germans in rearmament. On the contrary, they would increase their lead. However, despite all the arguments in favour of taking a strong stand now, which would almost certainly lead to war, I was so impressed by the fearful responsibility of incurring a war that might possibly be avoided, that I thought it worth while to postpone it in the very faint hope that some internal event might bring about the fall of the Nazi regime. But there were limits to the humiliation I was prepared to accept. If Hitler were willing to agree to a plebiscite being carried out under fair conditions with international control, I thought we could agree to it and insist upon the Czechs accepting it. At present we had no indication that Hitler was prepared to go so far. We reached no conclusion and separated at about 5.30.

(6) Neville Chamberlain held a Cabinet meeting on 24th September 1938. Duff Cooper wrote about it in his autobiography, Old Men Forget (1953)

The Cabinet met that evening. The Prime Minister looked none the worse for his experiences. He spoke for over an hour. He told us that Hitler had adopted a certain position from the start and had refused to budge an inch from it. Many of the most important points seemed hardly to have arisen during their discussion, notably the international guarantee. Having said that he had informed Hitler that he was creating an impossible situation, having admitted that he had "snorted" with indignation when he read the German terms, the Prime Minister concluded, to my astonishment, by saying that he considered that we should accept those terms and that we should advise the Czechs to do so.

It was then suggested that the Cabinet should adjourn, in order to give members time to read the terms and sleep on them, and that we should meet again the following morning. I protested against this. I said that from what the Prime Minister had told us it appeared to me that the Germans were still convinced that under no circumstances would we fight, that there still existed one method, and one method only, of persuading them to the contrary, and that was by instantly declaring full mobilisation. I said that I was sure popular opinion would eventually compel us to go to the assistance of the Czechs; that hitherto we had been faced with the unpleasant alternatives of peace with dishonour or war. I now saw a third possibility, namely war with dishonour, by which I meant being kicked into the war by the boot of public opinion when those for whom we were fighting had already been defeated. I pointed out that the Chiefs of Staff had reported on the previous day that immediate mobilisation was of urgent and vital importance, and I suggested that we might one day have to explain why we had disregarded their advice. This angered the Prime Minister. He said that I had omitted to say that this advice was given only on the assumption that there was a danger of war with Germany within the next few days. I said I thought it would be difficult to deny that such a danger existed.

(7) Duff Cooper, diary entry (30th September, 1938)

The full terms of the Munich agreement are in the papers this morning. At first sight I felt that I couldn't agree to them. The principle of invasion remains. The German troops are to march in tomorrow and the Czechs arc to leave all their installations intact. This means that they will have to hand over all their fortifications guns etc. upon which they have spent millions, and that they will receive no compensation for them. The international commission will enjoy increased powers but our representative on it is to be Nevile Henderson, who in my opinion has played a sorry part in the whole business and who is violently anti-Czech and pro-German. While I was dressing this morning I decided that I must resign.

I went to see Oliver Lyttelton at the Board of Trade. Walter Elliot was there They are both of opinion that we should accept these terms. Walter said he felt that if I went he ought to go too. I said that was not my view. It would be easier for me to go alone, as I had no wish to injure the Government, which I should not do if my resignation were the only one. We talked at some length and reached no conclusion.

When I got back to the Admiralty I learnt that there was to be a Cabinet at seven. The Prime Minister arrived at about twenty past seven amid scenes of indescribable enthusiasm. He spoke to the mob from the window. I felt very lonely in the midst of so much happiness that I could not share.

The Cabinet meeting lasted little more than half an hour. The Prime Minister explained the differences between the Munich and the Godesberg terms, and they are really considerably greater than I had understood. Nevertheless after a few questions had been asked and many congratulations had been offered, I felt it my duty to offer my resignation.

I said that not only were the terms not good enough but also that I was alarmed about the future. We must all admit that we should not have gone so far to meet Germany's demands if our defences had been stronger. It had more than once been said in Cabinet that after having turned the corner we must get on more rapidly with rearmament. But how could we do so when the Prime Minister had just informed the crowd that we had peace "for our time" and that we had entered into an agreement never to go to war with Germany.

The Prime Minister smiled at me in a quite friendly way and said that it was a matter to be settled between him and me. And so it was left.

(8) Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953)

On the following morning I went to see the Prime Minister. Our interview was as friendly as it was brief. I found it a relief to be in complete agreement with him for once. I think he was as glad to be rid of me as I was determined to go. I saw the King the same afternoon. He was frank and charming. He said that he could not agree with me, but he respected those who had the courage of their convictions.

I had thought that this would be the feeling of most people, but it was not. Great bitterness arose within the ranks of the Conservative Party and among their supporters. Political acquaintances cut me, and one old friend, a member of the executive committee of my constituency, on learning that I was to speak at a ward meeting which had been arranged to take place in his house, cancelled the meeting rather than allow me to cross the threshold.

That people who were ignorant of foreign affairs, as most English people are, should have felt as they did, was not surprising. For many days they had been preparing for war with all the anguish that such preparation inflicts upon the human mind. They had foreseen financial ruin and sudden death. Those who had survived the first war felt that it was all to be borne again, with the lives of their children, instead of their own, at stake. Suddenly, in the twinkling of an eye, the clouds dispersed, the sky was blue, the sun shone. There was to be no war, neither now nor at any future date. And this miracle had been performed by one man, and one man only. No ounce of credit for it was given to anyone else. The aged Prime Minister of England had saved the world. Even in France a subscription was raised to present him with a country house and a trout stream, for the French had learned that fishing was his favourite sport. At this great and glorious moment one of the hero's least considered colleagues had come forward and proclaimed his dissent, had resigned his office, and had disfigured the smiling landscape with a hideous blot.

(9) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (1st October, 1938)

Duff has resigned in what I must say is a very well-written letter, and the PM has immediately accepted his resignation. But we shall hear more of this - personally my reactions are mixed. I am sorry for Diana; they give up £5,000 per annum, a lovely house - and for what? Does Duff think he will make money at literature?

(10) Leo Amery, My Political Life (1955)

The great debate on Munich opened on the 3rd with Duff Cooper's personal statement. In a deeply moving speech

he affirmed his conviction that nothing short of much clearer statements on our part or an earlier mobilization of the Fleet could have made any impression on Hitler. It was not for Czechoslovakia that we should have been fighting, if Hitler had insisted on war, any more than it was for Serbia that we fought in 1914, but, as again and again in our history, to prevent Europe being dominated by brute force. He ended by saying that he had given up much, an office he loved, colleagues who were his friends, a leader whom he admired, but "I can still walk about the world with my head erect".

(11) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (3rd October, 1938)

The big debate began: and the crowded House was restless; when the PM took his seat directly in front of us, there was cheering, but not the hysterical enthusiasm of last Wednesday. Duff Cooper rose from the seat traditionally kept for the retiring, or resigning, the third corner seat immediately below the gangway - it was here I heard first Sam Hoare make his famous Mea Culpa over sanctions, and later Anthony Eden. Now it was Duff's turn, my plump, conceited, Duff. He did not impress the House and his arguments were flat, inconclusive, and the House took the speech as a dignified farewell from a man whom they were tired of, for Duff is definitely not a Parliamentarian. His defect is lack of imagination, which makes him a poor writer, although his English is distinguished.

(12) Lord Mountbatten, letter to Duff Cooper (1st October 1938)

I expect it is highly irregular of me, a serving naval officer, writing to you on relinquishing your position as First Lord, but I cannot stand by and see someone whom I admire behave in exactly the way I hope I should have the courage to behave if I had been in his shoes, without saying "Well done." Your going at this rime is a cruel blow to the Navy; none knows this better than I, who enjoyed to a certain measure your confidence. A great friend of mine has just written to me from Paris, "Until yesterday I did not think that one solitary statesman of the four powers who sold Czechoslovakia could possibly emerge with honour from the Crisis, but yesterday your First Lord emerged with great honour."

(13) A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965)

All the press welcomed the Munich agreement as preferable to war with the solitary exception of Reynolds News, a Left-wing Socialist Sunday newspaper of small circulation (and, of course, the Communist Daily Worker). Duff Cooper, first lord of the admiralty, resigned and declared that Great Britain should have gone to war, not to save Czechoslovakia, but to prevent one country dominating the continent 'by brute force'. No one else took this line in the prolonged Commons debate (3-6 October). Many lamented British humiliation and weakness. All acquiesced. Some thirty Conservatives abstained when Labour divided the house against the motion approving the Munich agreement; none voted against the government. The overwhelming majority of ordinary people, according to contemporary estimates, approved of what Chamberlain had done.