American Artists and the First World War

Max Eastman, the editor of The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in the fact that the articles and cartoons that appeared in journal attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons that had appeared in the magazine had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. The legal action that followed forced the magazine to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of the defendants.

Primary Sources

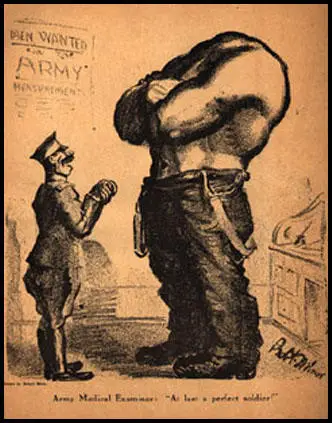

Robert Minor, The Masses (July, 1916)

(Source 3) Upton Sinclair, letter of resignation from the Socialist Party (September, 1917)

I have lived in Germany and know its language and literature, and the spirit and ideals of its rulers. Having given many years to a study of American capitalism. I am not blind to the defects of my own country; but, in spite of these defects, I assert that the difference between the ruling class of Germany and that of America is the difference between the seventeenth century and the twentieth.

No question can be settled by force, my pacifist friends all say. And this in a country in which a civil war was fought and the question of slavery and secession settled! I can speak with especial certainty of this question, because all my ancestors were Southerners and fought on the rebel side; I myself am living testimony to the fact that force can and does settle questions - when it is used with intelligence.

In the same way I say if Germany be allowed to win this war - then we in America shall have to drop every other activity and devote the next twenty or thirty years to preparing for a last-ditch defence of the democratic principle.

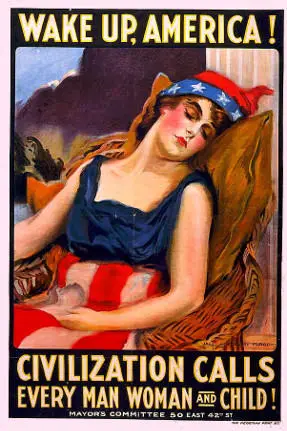

(Source 5) Cathy O'Brien, the granddaughter of James Montgomery Flagg, wrote in April 2001 about the background to his famous war poster (source 4).

James Montgomery Flagg first painted his famous Uncle Sam for a 4th of July 1916 issue of Leslie's Magazine. He was commissioned by the magazine in 1914, and reluctantly agreed when he finally saw what he believed to be the perfect model, a young soldier on a train.

Upon our involvement in WWI, the government contacted Flagg, requesting him to adapt his infamous figure into a war poster, and the rest is history.

(Source 7) The Masses (September, 1917)

The Post Office was represented by Assistant District Attorney Barnes. He explained that the Department construed the Espionage Act as giving it power to exclude from the mails anything which might interfere with the successful conduct of the war.

Four cartoons and four pieces of text in the August issue were specified as violations of the law. The cartoons were Boardman Robinson's Making the World Safe for Democracy, H. J. Glintenkamp's Liberty Bell and the conscription cartoons, and one by Art Young on Congress and Big Business. The conscription cartoon was considered by the Department "the worst thing in the magazine". The text objected to was A Question, an editorial by Max Eastman; A Tribute, a poem by Josephine Bell; a paragraph in an article on Conscientious Objectors; and an editorial, Friends of American Freedom.

(Source 9) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

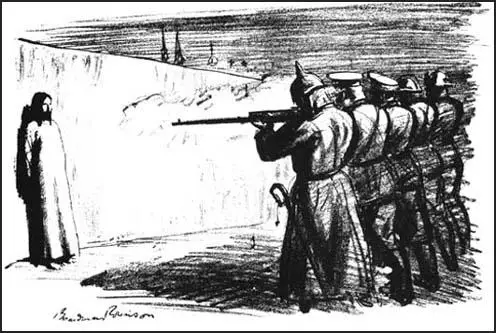

A regular contributor to The Masses was Boardman Robinson, then and perhaps permanently regarded as one of America's greatest artists. "His masterly drawings had the breath like delicacy as well as the power of the old Masters," in the judgment of a fellow artist, Reginald Marsh. Surprisingly as it may seem, he actually introduced into America the idea, as old as Daumier, that cartoons should have the values of art as well as of meaning.

He was big, burly, bluff, sea-captain sort of character, with dancing blue eyes under bushy red brows, a red beard, and a boisterous way of "blowing in" as though out of a storm, instead of merely entering, a place of habitation. Everybody called him Mike, and I guess it must have been in memory of Michelangelo, whose fury and rapture his powerful and meaningful drawings did recall.

When Mike blew in with a picture of a white-clad, saintly Jesus standing against a stone wall facing the rifles of a brutish firing squad - "The Deserter"- I felt that number (The Masses, July, 1916) deserved a place in the history of art.

(Source 11) Art Young was interviewed by Gil Wilson in May, 1940.

I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die.

(Source 13) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Art Young was in Eastman's view, the hero of the trial. Young, at fifty-two, was a nationally famous political cartoonist, who had been the Washington correspondent for the Metropolitan until 1917, and a contributor to Life, The Saturday Evening Post, and Collier's, in addition to the Masses. A member of the Socialist Party, he was a crusader for women's suffrage, labor unions, and racial equality.

One of the prosecution's pieces of evidence was a cartoon Young had drawn, showing a capitalist, an editor, a politician, and a minister dancing a war dance, while the devil directed the orchestra; it was captioned, "Having Their Fling." The prosecutor asked him what he meant by the picture.

"Meant? What do you mean by meant? You have the picture in front of you."

"What did you intend to do when you drew this picture, Mr. Young?"

"Intend to do? I intended to draw a picture." "For what purpose?"

"Why, to make people think - to make them laugh - to express my feelings. It isn't fair to ask an artist to go into the metaphysics of his art."

"Had you intended to obstruct recruiting and enlistment by such pictures?"

"There isn't anything in there about recruiting and enlistment is there? I don't believe in war, that's all, and I said so."

After hearing the bulk of the testimony, Judge Hand dismissed the part of the indictment that accused the Masses of conspiring to cause mutiny and refusal of duty in the armed forces; the only charge for the jury to weigh was that of a "conspiracy" to obstruct the draft.

In summing up, Hillquit said, in part: "Constitutional rights are not a gift. They are a conquest by this nation, as they were a conquest by the English nation. They can never be taken away, and if taken away, and if given back after the war, they will never again have the same potent vivifying force as expressing the democratic soul of a nation. They will be a gift to be given, to be taken."

The prosecuting attorney, Earl Barnes, was "sincerely convinced" that the Masses staff should go to jail, Eastman recalled. Yet he seemed equally sincere in his reluctance to send them there, and in his summation to the jury, made numerous complimentary references to the individual talents of the defendants.

Questions for Students

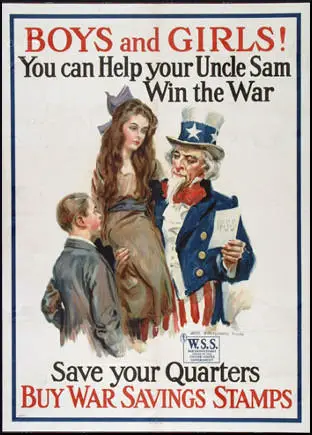

Question 1: Study sources 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12. Explain if the images are pro or anti the United States taking part in the First World War.

Question 2: Would the author of source 3 have liked source 6?

Question 3: Read source 5 and explain how he helps the production of source 4.

Question 4: Read source 9 and study source 2. Why do you think that Max Eastman believed The Deserter "deserved a place in the history of art"?

Question 5: Read the introduction and source 7 and explain why the authorities believed that some of the cartoons that had appeared in the The Masses had violated the Espionage Act.

Answer Commentary

A commentary on these questions can be found here

Download Activity

You can download this activity in a word document here

You can download the answers in a word document here