George Coppard

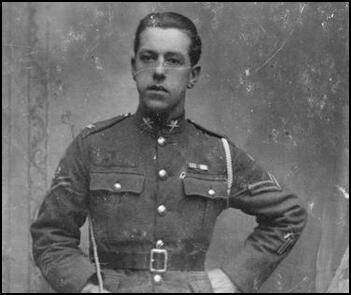

George Coppard was born in Brighton on 26th January, 1898. After attending Fairlight Place School he left at thirteen to work at a taxidermists.

Like many young men, Coppard volunteered to join the British Army in August, 1914. Although only sixteen, he was accepted after claimed he was three years older. He became a member of the Royal West Surrey Regiment and sent to Stoughton Barracks in Guildford for training.

Private Coppard was sent to France in June, 1915 as a member of a Vickers machine-gun unit. In September of that year he took part is the Artois-Loos offensive where the British Army suffered 50,000 casualties. The following he was involved in the Battle of the Somme.

On 17th October, 1916, Coppard was accidentally shot in the foot by one of his friends. For a while, Coppard was suspected of arranging the accident with his friend and he was sent to hospital with a label attached to his chest, SIW (Self-Inflicted Wound). Both men were eventually cleared of the charge but it was not until May, 1917, that Coppard was able to return to the Western Front. Soon afterwards, he took part in the Third Battle of Arras and in October, 1917, was promoted to the rank of corporal.

On 20th November, 1917, Coppard took part in the Battle of Cambrai. Coppard and other members of the Machine-Gun Corps followed 400 tanks across No Mans Land towards the German front-line. On the second day of the battle, Coppard was seriously wounded by a German machine-gunner. The bullet severed the femoral artery and it was only the swift action of a lance-corporal that used his boot-laces as a tourniquet that saved his life.

Discharged from the army in 1919, Coppard was unemployed for several months before becoming an assistant steward in a golf club. This was followed by periods as a warehouse clerk in Greenock, Scotland, and a waterguard officer in the Custom and Excise Department. In 1946 Coppard became an Executive Officer to the Ministry of National Insurance, a post he held until his retirement in 1962.

Coppard, who kept a diary during the First World War, decided to write an account of his experiences as a soldier on the Western Front. He sent a copy of his memoirs to the archives department of Imperial War Museum. Noble Frankland, the director of the museum, was so impressed with the manuscript that he arranged for it to have a larger audience. Coppard's book, With a Machine Gun to Cambrai was published in 1969. George Coppard died in 1984.

Primary Sources

(1) George Coppard was sixteen when he joined the Royal West Surrey Regiment on 27th August, 1914.

Although I seldom saw a newspaper, I knew about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo. News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared out their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnate, I knew I had to enlist straight away.

I presented myself to the recruiting sergeant at Mitcham Road Barracks, Croydon. There was a steady stream of men, mostly working types, queuing to enlist. The sergeant asked me my age, and when told, replied, "Clear off son. Come back tomorrow and see if you're nineteen, eh?" So I turned up again the next day and gave my age as nineteen. I attested in a batch of a dozen others and, holding up my right hand, swore to fight for King and Country. The sergeant winked as he gave me the King's shilling, plus one shilling and ninepence ration money for that day.

(2) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

The Vickers .303 water-cooled gun was a wonderful weapon, and its successful use led to the eventual formation of the Machine-Gun Corps, a formidable and highly-trained body of nearly 160,000 officers and men. Devotion to the gun became the most important thing in my life for the rest of my army career.

The Vickers gun proved to be most successful, being highly efficient, reliable, compact and reasonably light. The tripod was the heaviest component, weighing about 50 pounds; the gun itself weighed 28 pounds without water. In good tune the rate of fire was well over 600 rounds per minute, and with the gun was firmly fixed on the tripod there was little or no movement to upset its accuracy. Being water-cooled, it could fire continuously for long periods. Heat engendered by the rapid fire soon boiled the water and caused a powerful emission of steam, which was condensed by passing it through a pliable tube into a canvas bucket of water. By this means the gun could continue to fire without a cloud of steam giving its position away to the enemy.

There were normally six men in a gun team. Number One was leader and fired the gun, while Number Two controlled the entry of ammo belts into the feed-block. Number Three maintained a supply of ammo to Number Two, and Number Four to Six were reserves and carriers, but all the members of the team were fully trained in handling the gun. In the trenches the Vickers were primarily used for defence, but it was also effectively used to assist an attack, by indirect or barrage fire, and to restrict and harass enemy movement behind their lines.

When in reserve, it was normal routine in the machine gun section to give guns, accessories and equipment a complete overhaul. Most of us were dedicated enthusiasts, and strove to maintain the weapons at peak efficiency. Gun barrels had an average life of 18,000 rounds of firing, after which accuracy fell off. A spare barrel was carried for replacement when necessary.

(3) George Coppard arrived at the Western Front on 21st June, 1915.

The day really began at stand-to. Past experience had shown that the danger period for attack was at dawn and dusk, when the attacker, having the initiative, could see sufficiently to move forward and cover a good distance before being spotted. About half an hour or so before dawn and dusk the order, 'Stand to," was given and silently passed throughout the length of the battalion front. In this way, the whole Allied front line system became alerted. When daylight came the order, 'Stand down', passed along the line. Tension slackened, but sentries still kept watch by periscope or by a small mirror clipped to the top of a bayonet.

Breakfast over, there was not long to wait before an officer appeared with details of the duties and fatigues to be performed. Weapon cleaning and inspection, always a prime task, would soon be followed by pick and shovel work. Trench maintenance was constant, a job without end. Owing to the weather or enemy action, trenches required repairing, deepening, widening and strengthening, while new support trenches always seemed to be wanted. The carrying of rations and supplies from the rear went on interminably.

(4) George Coppard took part in the Battle of Loos in September, 1915.

We reached the top of the slope where the German front line had been before the attack. And there, stretching for several hundred yards on the right of the road lay masses of British dead, struck down by machine-gun and rifle fire. Shells from enemy field batteries had been pitching into the bodies, flinging some into dreadful postures. Being mostly of Highland regiments, there was a fantastic display of colour from their kilts, glengarries and bonnets, and also from the bloody wounds on their bare limbs. The warm weather had darkened their faces and, shrouded as they were with the sickly odour of death, it was repulsive to be near them. Hundreds of rifles lay about, some stuck in the ground on the bayonet, as though impaled at the very moment of the soldier's death as he fell forward.

(5) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

Le Touquet consisted of a number of huge mine craters, roughly between the German front line and our own. In some cases the edge of one crater overlapped that of another. Companies of Royal Engineers, composed of specially selected British coal miners, worked in shifts around the clock digging tunnels towards the German line. When a tunnel was completed after several days of sweating labour, tons of explosive charges were stacked at the end and primed ready for firing. Careful calculations were made to ensure that the centre of the explosion would be bang under the target area.

This was an underground battle against time, with both sides competing against each other to blast great holes through the earth above. With listening apparatus the rival gangs could judge each other's progress, and draw conclusions. A continual contest went on. As soon as a mine was blasted, preparations for a new tunnel were started. On at least one occasion British and German miners clashed and fought underground, when the final partition of earth between them suddenly collapsed.

On the completion of one of the mines, the troops in the danger area withdrew when zero time for detonation was imminent. If the resultant crater had to be captured, an infantry storming party would be ready to rush forward and beat Jerry to it. Some of the craters measured over a hundred feet across the top, descending funnell-wise to a depth of at least thirty feet.

At the moment of explosion the ground trembled violently in a miniature earthquake. Then, like an enormous pie crust rising up, slowly at first, the bulging mass of earth crackled in thousands of fissures as it erupted. When the vast sticky mass could no longer contain the pressure beneath, the centre burst open, and the energy released carried all before it. Hundreds of tons of earth hurled skywards to a height of three hundred feet or more, many of the lumps of great size. A state of acute alarm prevailed as the deadly weight commenced to drop, scattered over a huge radial area from the centre of the blast.

(6) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

A full day's rest allowed us to clean up a bit, and to launch a full scale attack on lice. I sat in a quiet corner of a barn for two hours delousing myself as best I could. We were all at it, for none of us escaped their vile attentions. The things lay in the seams of trousers, in the deep furrows of long thick woolly pants, and seemed impregnable in their deep entrenchments. A lighted candle applied where they were thickest made them pop like Chinese crackers. After a session of this, my face would be covered with small blood spots from extra big fellows which had popped too vigorously. Lice hunting was called 'chatting'. In parcels from home it was usual to receive a tin of supposedly death-dealing powder or pomade, but the lice thrived on the stuff.

(7) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

Rats bred by the tens of thousands and lived on the fat of the land. When we were sleeping in funk holes the things ran over us, played about, copulated and fouled our scraps of food, their young squeaking incessantly. There was no proper system of waste disposal in trench life. Empty tins of all kinds were flung away over the top on both sides of the trench. Millions of tins were thus available for all the rats in France and Belgium in hundreds of miles of trenches. During brief moments of quiet at night, one could hear a continuous rattle of tins moving against each other. The rats were turning them over. What happened to the rats under heavy shell-fire was a mystery, but their powers of survival kept place with each new weapon, including poison gas.

(8) George Coppard arrived at the Western Front on 21st June, 1915.

Bullets skimming the top of the parapet took on a lightning changes of direction after they had ricocheted. In a crowded trench it was not uncommon for two or even three men to be hit by a ricochet. Jarvis was shot clean through the neck by a ricochet when standing close beside me. He bled severely, and when carted off we felt sure he was a goner, but, far from pegging out, he never got beyond the base hospital. The bullet had passed through his neck without rendering a vital part and, the wound quickly healing, he was back in the front line in a few weeks. This was tough luck really, as he deserved a spell in Blighty.

Some men seemed to get wounded as soon as they arrived in the front line. One Tommy I knew had three separate wounds all received in the front line, and his total service in the trenches was but ten days in all. He got his third wound when mounting a ladder to go over the top in an attack. He slipped backwards and was impaled on the bayonet of the Tommy behind him, causing a deep and ugly gash, which got him to Blighty. The prospect of getting a 'blighty one' was the fond hope of most men.

(9) George Coppard was granted compassionate leave after his stepfather was killed on the Western Front in January, 1916.

I arrived in England on my 18th birthday, 26th January 1916. It had become the fashion to welcome home troops at Victoria Station. People pressed forward from the waiting crowds and gave me packets of cigarettes and chocolate. Religious organizations provided lashings of buffet fare and hot drinks. It was just marvellous for a Tommy's homecoming. Leave men carried their rifles, and this usually indicated that they had arrived from the front. Most people knew this, and when I went into a pub at East Croydon it never cost me a penny. It was a wonderful thing to feel that people really did care about the Tommies.

(10) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

On my frequent visits to company HQ I saw the kind of life the officers led when not in the front line or on patrol. Their greatest comfort was sleeping-bags and blankets, and room to stretch out for sleep. Batmen were handy to fetch and carry. Meals and drinks were prepared and placed before them. In addition to rum, whisky was also available. Cartoons and pin-ups decorated the walls, and there was never a lack of the precious weed. Such things, and many other small trifles, demonstrated the great difference between the creature comforts of the officers, and the almost complete absence of them for the men. That's what the war was like.

(11) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

Historians say that Haig had the confidence of his men. I very much doubt whether this was strictly true. He had such a vast number of troops under his command and was so completely remote from the actual fighting that he was merely a name, a figurehead. In my view, it was not confidence in him that the men had, but simply their ingrained sense of duty and obedience, in keeping with the times. They were wholly loyal to their own officers, and that was as far as their confidence went. It was trust and comradeship founded on the actual sharing of dangers together.

(12) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

On my frequent visits to company HQ I saw the kind of life the officers led when not in the front line or on patrol. Their greatest comfort was sleeping-bags and blankets, and room to stretch out for sleep. Batmen were handy to fetch and carry. Meals and drinks were prepared and placed before them. In addition to rum, whisky was also available. Cartoons and pin-ups decorated the walls, and there was never a lack of the precious weed. Such things, and many other small trifles, demonstrated the great differences between the creature comforts of the officers, and the almost complete absence of them for the men. That's what the war was like.

(13) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

One fine evening two military policemen appeared with a handcuffed prisoner, and, in full view of the crowd and villagers, tied him to the wheel of a limber, cruciform fashion. The poor devil, a British Tommy, was undergoing Field Punishment Number One, and this public exposure was part of the punishment. There was a dramatic silence as every eye watched the man being fastened to the wheel, and some jeering started. Lashing men to a wheel in public was one of the most disgraceful things in the war. Troops resented these exhibitions, but they continued until 1917, when the War Minister put a stop to them, following protests in Parliament.

I believe that an important modification of the death sentence also took place in 1917. It appeared that the military authorities were compelled to take heed of the clamour against the death sentences imposed by courts martial. There had been too many of them. As a result, a man who would otherwise have been executed was instead compelled to take part in the fore-front of the first available raid or assault on the enemy. He was purposely placed in the first wave to cross No Man's Land and it was left to the Almighty to decide his fate. This was the situation as we Tommies understood it, but nothing official reached our ears. Let the War Office dig out its musty files and tell us how many men were treated in this way, and how many survived the cruel sentences. Shylock, in demanding his pound of flesh, had got nothing on the military bigwigs in 1917.

(14) George Coppard was a machine-gunner at the Battle of the Somme. In his book With A Machine Gun to Cambrai, he described what he saw on the 2nd July, 1916.

The next morning we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of our trench. There was a pair of binoculars in the kit, and, under the brazen light of a hot mid-summer's day, everything revealed itself stark and clear. The terrain was rather like the Sussex downland, with gentle swelling hills, folds and valleys, making it difficult at first to pinpoint all the enemy trenches as they curled and twisted on the slopes.

It eventually became clear that the German line followed points of eminence, always giving a commanding view of No Man's Land. Immediately in front, and spreading left and right until hidden from view, was clear evidence that the attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead, many of the 37th Brigade, were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high-water mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in the net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as though they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. From the way the dead were equally spread out, whether on the wire or lying in front of it, it was clear that there were no gaps in the wire at the time of the attack.

Concentrated machine gun fire from sufficient guns to command every inch of the wire, had done its terrible work. The Germans must have been reinforcing the wire for months. It was so dense that daylight could barely be seen through it. Through the glasses it looked a black mass. The German faith in massed wire had paid off.

How did our planners imagine that Tommies, having survived all other hazards - and there were plenty in crossing No Man's Land - would get through the German wire? Had they studied the black density of it through their powerful binoculars? Who told them that artillery fire would pound such wire to pieces, making it possible to get through? Any Tommy could have told them that shell fire lifts wire up and drops it down, often in a worse tangle than before.

(15) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

On 17th October, 1916, I was shot through the left foot by a .45 bullet from Snowy's revolver. The bullet tore between two bones in front of the ankle, went through the instep of my boot and buried itself in the ground. With his revolver pointed down, and not realising that it was loaded, Snowy had casually pulled the trigger and wham! I was out of the fighting for six months. There was pandemonium for a few moments as I hobbled about in pain, and then I found myself on the back of a comrade named Grigg, who carried me to a field dressing station close by. Poor Snowy was put under open arrest pending an inquiry.

Transferred to an ambulance car, I became puzzled to find myself the only casualty in it. Finally I arrived at the 39th Casualty Clearing Station. Next morning I discovered that there was something queer about the place which filled me with misgivings. None of the nursing staff appeared friendly, and the matron looked, and was, a positive battle-axe. I made anxious inquiries, and quickly learned that I was classed as a suspected self-inflicted wound case. Unknown to me, the letters SIW with a query mark added had been written on the label attached to my chest.

(16) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

I feel I must mention a piece of psychological propaganda put about by some War Office person, which brought poor comfort to Tommies. The story swept the world and, being gullible, we in the trenches were taken in by it for a while. With slight variations it indicated that the German war industry was in a bad way, and was short of fats for making glycerine. To overcome the shortage a vast secret factory had been erected in the Black Forest, to which the bodies of dead British soldiers were despatched. The bodies, wired together in bundles, were pitchforked on to conveyor belts and moved into the factory for conversion into fats. War artists got busy, and dreadful scenes were depicted and published in Britain. The effect on me at first was despondency. Death was not enough apparently. The idea of finishing up in a stew pot was bloody awful, but as I had so many immediate problems the story soon lost its evil potency for me.

(17) On 20th November, 1917, George Coppard took part in the Battle of Cambrai.

At 6.30 am on that memorable day, 20th November. We heard the sound of tank engines warming up. The first glimpse of dawn was beginning to show as we stood waiting for the big bang that would erupt behind us at the end of the count down. The tanks, looking like giant toads, became visible against the skyline as they approached the top of the slope. Some of the leading tanks carried huge bundles of tightly-bound brushwood, which they dropped when a wide trench was encountered, thus providing a firm base to cross over. It was broad daylight as we crossed No Man's Land and the German front line. I saw very few wounded coming back, and only a handful of prisoners. The tanks appeared to have busted through any resistance. The enemy wire had been dragged about like old curtains.

(18) George Coppard was shot by a German machine-gunner at the Battle of Camprai on 22nd November, 1917.

We stopped to look at a map and for a few moments remained motionless. Some undiscovered Jerry machine gunner, destined to take a hand in my affairs, pressing a trigger and a hail of bullets clove the air. I fell as a bullet passed clean through the thickest part of my left thigh, severing the femoral artery. The Jerry gun continued firing as the three of us lay on the ground, the gunner hoping to polish us off. How can I describe my feelings as I lay, the cone of the bullets scything the grass, knowing that I had already caught a packet. When the gun stopped my two companions bravely got to work, and when they ripped open the leg of my trousers a spout of blood curved upwards like a scarlet arc, three feet long and as thick as a pencil, then disappeared into the ground. To stop the blood I bunged my thumb on the hole it spouted from. I was aware I had broken the rules which said that wounds should not be touched by hand, but my action stopped the flow like turning off a tap. The lance-corporal rigged up my boot-laces as a tourniquet, and lashed it round my thigh above the wound.

(19) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

I was demobbed a few days after my 21st birthday, after four and a half years of service. My leg had shrunk a bit and I was given a pension of twenty-five shillings per week for six months. Dropping to nine shillings per week for a year, the pension ceased altogether.

During this time the government, in the flush of victory, were busily engaged in fixing the enormous sums to be voted as gratuities to the high-ranking officers who had won the war for them. Heading the formidable list were Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and Admiral Sir David Beatty. For doing the jobs for which they were paid, each received a tax-free golden handshake of £100,000 (a colossal sum then), an earldom and, I believe, an estate to go with it. Many thousands of pounds went to leaders lower down the scale. Sir Julian Byng picked up a trifle of £30,000 and was made a viscount. If any reader should ask, 'What did the demobbed Tommy think about all this?' I can only say, 'Well, what do you think?'