The Siege of Sidney Street

On 21st November, 1910, Max Smoller, using the name, Joe Levi, he asked to rent a house, 11 Exchange Buildings. His rent was ten shillings a week, and he took possession on 2nd December. Fritz Svaars rented 9 Exchange Buildings on 12th December. He told the landlord that he wanted it for two or three weeks to store Christmas goods and paid five shillings deposit. Another friend, George Gardstein, borrowed money so that he could buy a quantity of chemicals, a a book on brazing metals and cutting metals with acid.

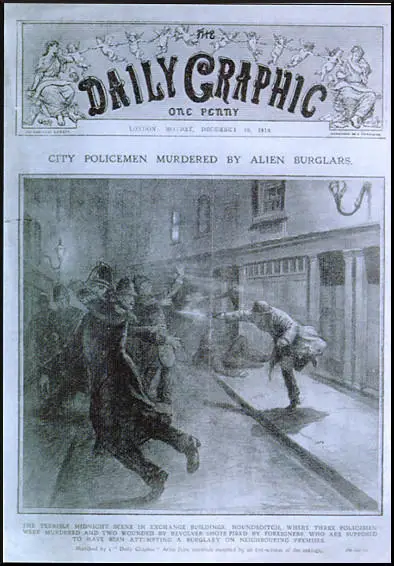

On 16th December 1910, a gang that is believed to included Smoller, Svaars, Gardstein, Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof, Karl Hoffman, John Rosen and William Sokolow, attempted to break into the rear of Henry Harris's jeweller's shop in Houndsditch, from Exchange Buildings in the cul-de-sac behind. The Daily Telegraph reported: "Some two or three weeks ago this particular house in Exchange Buildings was rented and there went to live there two men and a woman. They were little known by neighbours, and kept very quiet, as if, indeed, to escape observation. They are said to have been foreigners in appearance, and the whole neighbourhood of Houndsditch containing a great number of aliens, and removal being not infrequent, the arrival of this new household created no comment. The police, however, evidently had some cause to suspect their intentions. The neighbourhood is always well patrolled. Shortly before 11.30 last night there were sounds either at the back of these newcomers' premises or at Mr Harris's shop that attracted the attention of the police."

A neighbouring shopkeeper, Max Weil, heard their hammering, informed the City of London Police, and nine unarmed officers arrived at the house. Sergeant Robert Bentley knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings. The door was open by Gardstein and Bentley asked him: "Have you been working or knocking about inside?" Bentley did not answer him and withdrew inside the room. Bentley gently pushed open the door, and was followed by Sergeant Bryant. Constable Arthur Strongman was waiting outside. "The door was opened by some person whom I did not see. Police Sergeant Bentley appeared to have a conversation with the person, and the door was then partly closed, shortly afterwards Bentley pushed the door open and entered."

The Houndsditch Murders

According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "Bentley stepped further into the room. As he did so the back door was flung open and a man, mistakenly identified as Gardstein, walked rapidly into the room. He was holding a pistol which he fired as he advanced with the barrel pointing towards the unarmed Bentley. As he opened fire so did the man on the stairs. The shot fired from the stairs went through the rim of Bentley's helmet, across his face and out through the shutter behind him... His first shot hit Bentley in the shoulder and the second went through his neck almost severing his spinal cord. Bentley staggered back against the half-open door and collapsed backwards over the doorstep so that he was lying half in and half out of the house."

Sergeant Bryant later recalled: "Immediately I saw a man coming from the back door of the room between Bentley and the table. On 6 January I went to the City of London Mortuary and there saw a dead body and I recognised the man. I noticed he had a pistol in his hand, and at once commenced to fire towards Bentley's right shoulder. He was just in the room. The shots were fired very rapidly. I distinctly heard 3 or 4. I at once put up my hands and I felt my left hand fall and I fell out on to the footway. Immediately the man commenced to fire Bentley staggered back against the door post of the opening into the room. The appearance of the pistol struck me as being a long one. I think I should know a similar one again if I saw it. Only one barrel, and it seemed to me to be a black one. I next remember getting up and staggered along by the wall for a few yards until I recovered myself. I was going away from Cutler Street. I must have been dazed as I have a very faint recollection of what happened then."

Constable Ernest Woodhams ran to help Bentley and Bryant. He was immediately shot by one of the gunman. The Mauser bullet shattered his thigh bone and he fell unconscious to the ground. Two men with guns came from inside the house. Strongman later recalled: "A man aged about 30, height 5 ft 6 or 7, pale thin face, dark curly hair and dark moustache, dress dark jacket suit, no hat, who pointed the revolver in the direction of Sergeant Tucker and myself, firing rapidly. Strongman was shot in the arm, but Sergeant Charles Tucker was shot twice, once in the hip and once in the heart. He died almost instantly.

The Death of George Gardstein

As George Gardstein left the house he was tackled by Constable Walter Choat who grabbed him by the wrist and fought him for possession of his gun. Gardstein pulled the trigger repeatedly and the bullets entered his left leg. Choat, who was a big, muscular man, 6 feet 4 inches tall, managed to hold onto Gardstein. Other members of the gang rushed to his Gardstein's assistance and turned their guns on Choat and he was shot five more times. One of these bullets hit Gardstein in the back. The men pulled Choat from Gardstein and carried him from the scene of the crime.

Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof, Peter Piaktow, Fritz Svaars, and Nina Vassilleva half dragged and half carried Gardstein along Cutler Street. Isaac Levy, a tobacconist, nearly collided with them. Peters and Dubof lifted their guns and pointed them at Levy's face and so he let them pass. For the next half-hour they were able to drag the badly wounded man through the East End back streets to 59 Grove Street. Nina and Max Smoller went to a doctor who they thought might help. He refused and threatened to tell the police.

They eventually persuaded Dr. John Scanlon, to treat Gardstein. He discovered that Gardstein had a bullet lodged in the front of the chest. Scanlon asked Gardstein what had happened. He claimed that he had been shot by accident by a friend. However, he refused to be taken to hospital and so Scanlon, after giving him some medicine to deaden the pain and receiving his fee of ten shillings, he left, promising to return later. Despite being nursed by Sara Trassjonsky, Gardstein died later that night.

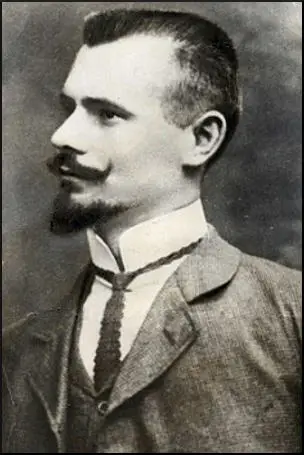

The following day Dr. Scanlon told the police about treating Gardstein for gun-shot wounds. Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley and Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson arrived to find Trassjonsky burning documents. Soon afterwards, a Daily Chronicle journalist arrived: "The room itself is about ten feet by nine, and about seven feet high. A gaudy paper decorates the walls and two or three cheap theatrical prints are pinned up. A narrow iron bedstead painted green, with a peculiarly shaped head and foot faces the door. On the bedstead was a torn and dirty woollen mattress, a quantity of blood-stained clothing, a blood-stained pillow and several towels also saturated with blood. Under the window stood a string sewing machine, and a rickety table, covered with a piece of mole cloth, occupied the centre of the room. On it stood a cup and plate, a broken glass, a knife and fork, and a couple of bottles and a medicine bottle. Strangely contrasting with the dirt and squalor, a painted wooden sword lay on the table, and another, to which was attached a belt of silver paper, lay on a broken desk supported on a stool. On the mantelpiece and on a cheap whatnot stood tawdry ornaments. In an open cupboard beside the fireplace were a few more pieces of crockery, a tin or two, and a small piece of bread. A mean and torn blind and a strip of curtain protected the window, and a roll of surgeon's lint on the desk. The floor was bare and dirty, and, like the fireplace, littered with burnt matches and cigarette ends - altogether a dismal and wretched place to which the wounded desperado had been carried to die." Another journalist described the dead man "as handsome as Adonis - a very beautiful corpse."

The Hunt for Fritz Svaars and Peter the Painter

The police found a Dreyse gun and a large amount of ammunition for a Mauser gun in the room. In Gardstein's pocket book was a member's card dated 2nd July, 1910, certifying that he was a member of Leesma, the Lettish Communist Group. There was also a letter from Fritz Svaars: "All around I see awful things which I cannot tell you. I do not blame our friends as they are doing all that is possible, but things are not getting better. The life of the workman is full of pain and suffering, but if the suffering reaches a certain degree one wonders whether it would not be better to follow the example of Rainis (an author of Lettish poems) who says burn at once so that you may not suffer long, but one feels that one cannot do it although it seems very advisable. The outlook is always the same, awful outlook for which we must sacrifice our strength. There is not and cannot be another outlet. Under such circumstances, our better feelings are at war with those who live upon our labour. The weakest part of our organisation is that we cannot do sufficient for our friends who are falling."

Despite the fact that these men were Lettish communists linked to the Bolsheviks, the media continued to argue that they were Russian Anarchists: The Daily Telegraph reported: "Anarchist literature, in sufficient quantities to corroborate the suspicion of the police that they are face to face with a far-reaching conspiracy, rather than an isolated and unpremeditated attack on civil authority, is stated to have been recovered. It is reported, in addition, that a dagger was found and a belt, which is understood to have had placed within it 150 Mauser dumdum bullets - bullets, that is, with soft heads, which, upon striking a human body, would spread and inflict a wound of a grievous, if not fatal character."

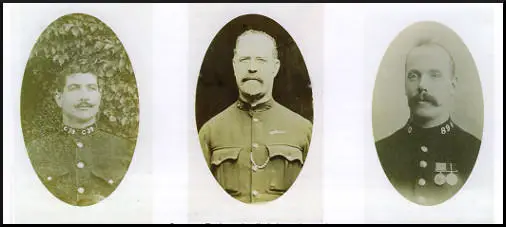

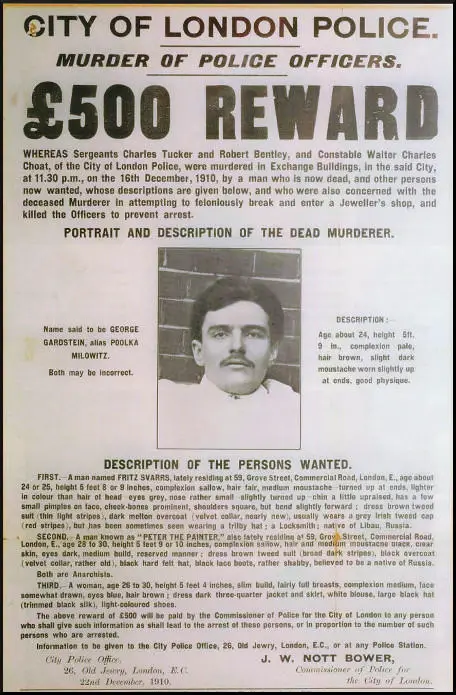

The police offered a £500 reward for the capture of the men responsible for the deaths of Charles Tucker, Robert Bentley and Walter Choat. One man who came forward was Nicholas Tomacoff, who had been a regular visitor to 59 Grove Street. He told them that he knew that identities of three members of the gang. This included Yakov Peters. On 22nd December, 1910, Tomacoff took the police to 48 Turner Street, where Peters was living. When he was arrested Peters answered: "It is nothing to do with me. I can't help what my cousin Fritz (Svaars) has done."

Tomacoff also provided information on Yourka Dubof. He was described as "twenty-one, 5 feet 8 inches in height of pale complexion, with dark-brown hair". When he was arrested he commented: "You make mistake. I will go with you." He admitted that he had been at 59 Grove Street on the afternoon of 16th December 1910. He said he had gone to see Peter, who he knew was a painter, in an attempt to find work, as he had just been sacked from his previous job. At the police station Dubof and Peters were identified by Isaac Levy, as two of the men carrying George Gardstein in Cutler Street.

The City of London Police now issued a wanted poster with descriptions of two of the men, Fritz Svaars and Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), that Tomacoff had told them about: "Fritz Svarrs, lately residing at 59 Grove Street... age about 24 or 25, height 5 feet 8 or 9 inches, complexion sallow, hair fair, medium moustache - turned up at ends, lighter in colour than hair of head - eyes grey, nose rather small - slightly turned up - chin a little upraised, has a few small pimples on face, cheek-bones prominent, shoulders square but bend slightly forward: dress brown tweed suit (thin light stripes), dark melton overcoat (velvet collar, nearly new), usually wears a grey Irish tweed cap (red stripes), but has been sometimes seen wearing a trilby hat."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter)

The police did not have the name of the second wanted man: "A man known as Peter the Painter, also lately residing at 59 Grove Street... age 28 to 30, height 5 feet 9 or 10 inches, complexion sallow, hair and medium moustache black, clear skin, eyes dark, medium build, reserved manner; dress brown tweed suit (broad dark stripes), black overcoat (velvet collar, rather old), black hard felt hat, black lace boots, rather shabby, believed to be a native of Russia. Both are Anarchists."

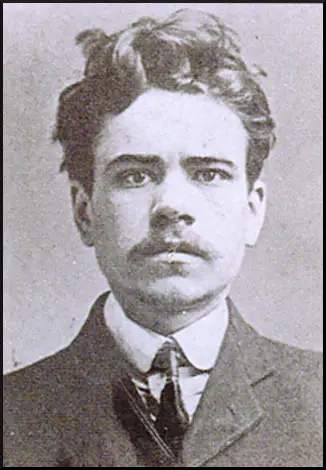

The poster also included a photograph of a dead George Gardstein, who was described as "age about 24, height 5 feet 9 inches, complexion pale, hair brown, slight dark moustache worn slightly up at ends, good physique." The poster also contained the information: "The above reward of £500 will be paid by the Commissioner of Police for the City of London to any person who shall give such information as shall lead to the arrest of these persons, or in proportion to the number of such persons who are arrested."

Nina Vassilleva and John Rosen wanted by the Police

Several witnesses had seen Nina Vassilleva with George Gardstein. Soon after the murders the police issued the following description: "Age 26 to 30; 5ft 4in; slim build, full breasts; complexion medium, face drawn; eyes blue; hair brown; dress, dark blue, three quarters jacket and skirt, white blouse, large black hat trimmed with silk." It was such a vague description that Isaac and Fanny Gordon, who rented a room to Nina, did not recognise her.

However, they did become concerned when they discovered that she had died her hair a "harsh, ugly black". Isaac Gordon also discovered her burning documents. According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "She told Isaac that she was the woman who had been living in Exchange Buildings and that she had heard that the police were going to carry out house-to-house searches; she did not want them to find these papers. Isaac pleaded with her to let him have them for safe keeping." Nina told Isaac: "It would have been better if they had shot me, instead of the man they have shot. He was the best friend I had... Without him I might just as well be dead." Nina agreed not to burn anymore documents and gave them to Isaac.

John Rosen went to visit Nina Vassilleva on the 18th December, 1910. She asked him "have you brought trouble". He gave a slight shrug and said "I don't know". Nina refused to let him in and he left the building. Ten minutes later Detective Inspector Wensley arrived. Issac Gordon had given Nina's documents to the police. After she denied knowing George Gardstein Wensley showed her the collection of photographs she had given Gordon that included one of her former lover.

Wensley did not arrest her straight away as he hoped she would lead them to the rest of the gang. Nina decided to flee to France but changed her plan when she discovered she was being followed. She told a friend: "If I go to Russia I shall be killed and if I stop here I shall be hanged." On 23rd December, detectives followed her to St Paul's Cathedral to watch the funeral of the three murdered policemen. They saw her purchase a small black-and-silver memorial card, with wood-block portraits of the three dead men.

Nina Vassilleva was arrested while walking along Sidney Street and she appeared in court on 14th February and was charged with conspiracy to commit a robbery. When the police searched her room they found the blue three-quarter-length coat she had been wearing on the night of the murders, and which still had large patches of dried blood on the front.

John Rosen went into hiding but in early January 1911 he told his girlfriend, Rose Campbell, that he had been involved with the Peter the Painter gang. She in turn confided in her mother, who told her son-in-law Edward Humphreys, who went to the police. Rose denied the story and on 31st January, she married Rosen. Rosen was arrested on 2nd February. His first words were "I know you have come to arrest me." Rosen admitted visiting 59 Grove Street on the day of the murders but said that he had spent the evening with Karl Hoffman at the pictures, and later in his room, before going home. The following day he met Hoffman again but he said he knew nothing about the murders. However, Rosen did tell the police "I could show you where a man and a woman live, or were living, who are concerned in it, but I don't know if they have moved since I have been here."

On 15th February, 1911, Karl Hoffman was charged with conspiracy to break and enter into the Henry Harris's jeweller's shop. When questioned he refused to admit that he knew George Gardstein, Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), Yakov Peters, Max Smoller, Fritz Svaars, John Rosen and William Sokolow. Hoffman claimed that on 16th December he had gone to bed at midnight and nobody had visited his room. The only witnesses against Hoffman were Nicholas Tomacoff and the landlady at 35 Newcastle Place, who both seen him, on separate occasions, in Svaars' lodgings.

Theodore Janson, a Russian immigrant and a police informer, claimed that he had asked Hoffman on Christmas Day if Peters and Dubof, who had been arrested, were guilty of the murders. Hoffman had apparently laughed and replied: "No, there were nine men in the plot, none of them are yet arrested. It's a pity the man is dead (meaning George Gardstein), he was the ablest of the lot and leader of the gang. He also managed it that some members of the gang didn't know the others."

The Siege of Sidney Street

On 1st January, 1911, the police was told that they would find the men in the lodgings rented by a Betsy Gershon at 100 Sidney Street. It seems that one of the gang, William Sokolow, was Betsy's boyfriend. This was part of a block of 10 houses just off Commercial Road. The tenant was a ladies tailor, Samuel Fleischmann. With his wife and children he occupied part of the house and sublet the rest. Other residents included an elderly couple and another tailor and his large family. Betsy had a room at the front of the second floor.

Superintendent Mulvaney was put in charge of the operation. At midday on 2nd January, two large horse-drawn vehicles concealing armed policeman were driven into the street and the house placed under observation. By the afternoon over 200 officers were on the scene, with armed men stationed in shop doorways facing the house. Meanwhile, plain-clothed policemen began to evacuate the residents of 100 Sidney Street.

Mulvaney decided that any attempt to arrest the men would be very difficult. He later recalled: "The measurements of the passage and staircase will show how futile any attempt to storm or rush the place would have been, with two men... dominating the position from the head of the stairs and where, to an extent, they were well under cover from fire. The passage at one discharge would have been blocked by fallen men; had any even reached the stairs, it could only have been by climbing over the bodies of their comrades, when they would stand little chance of getting further; had they even done this the two desperadoes could retreat up the staircase to the first and second storey, on each of which, what had occurred below would have been repeated."

At daybreak Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley gave orders for a brick to be thrown at the window of Betsy Gershon's room. The men inside responded by firing their guns. Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson was hit and collapsed to the ground. Wensley went to help him. Leeson is recorded as saying: "Mr Wensley, I am dying. They have shot me through the heart. Goodbye. Give my love to the children. Bury me at Putney." Dr. Nelson Johnstone examined him and discovered the wound was level with the left nipple and about two inches in towards the centre of the chest.

Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, decided to go to Sidney Street. His biographer, Clive Ponting, commented: "His presence had been unnecessary and uncalled for - the senior Army and police officers present could easily have coped with the situation on their own authority. But Churchill with his thirst for action and drama could not resist the temptation." As soon as he arrived Churchill ordered the troops to be called in. This included 21 Scots Guards marksmen who took up their places on the top floor of a nearby building.

Philip Gibbs, was reporting the Siege of Sidney Street for the The Daily Chronicle and had positioned himself on the roof of The Rising Sun public house: "In the top-floor room of the anarchists' house we observed a gas jet burning, and presently some of us noticed the white ash of burnt paper fluttering out of a chimney pot... They were setting fire to the house, upstairs and downstairs. The window curtains were first to catch alight, then volumes of black smoke, through which little tongues of flame licked up, poured through the empty window frames. They must have used paraffin to help the progress of the fire, for the whole house was burning with amazing rapidity."

Assistant Divisional Officer of the London Fire Brigade, Cyril Morris, was told to report to Winston Churchill: "As I arrived at the fire. I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen - thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must he there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house. from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols. I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations." Morris was shocked when Churchill told him to "Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders."

Philip Gibbs described how the men inside the house fired on the police: "For a moment I thought I saw one of the murderers standing on the window sill. But it was a blackened curtain which suddenly blew outside the window frame and dangled on the sill. A moment later I had one quick glimpse of a man's arm with a pistol in his hand. He fired and there was a quick flash. At the same moment a volley of shots rang out from the Guardsmen opposite. It is certain that they killed the man who had shown himself, for afterwards they found his body (or a bit of it) with a bullet through the skull. It was not long afterwards that the roof fell in with an upward rush of flame and sparks. The inside of the house from top to bottom was a furnace. The detectives, with revolvers ready, now advanced in Indian file. One of them ran forward and kicked at the front door. It fell in, and a sheet of flame leaped out. No other shot was fired from within."

Cyril Morris was one of those who searched the building afterwards: "We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas."

The police identified the two dead men as Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. It was believed that Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter) had escaped from the burning building. The bodies were taken to Ilford Cemetery and carried into the church. When the chaplain was told of their identity he expressed his strong disapproval of their bodies being brought into the church and said that it was an outrage to public decency that they should be buried in the same ground as two of the murdered policemen. Later that day they were buried in unconsecrated ground without a religious service.

Winston Churchill and the Siege of Sidney Street

Winston Churchill was heavily criticised for the way he had handled the Siege of Sidney Street crisis. Philip Gibbs, reporting for the The Daily Chronicle argued: "Mr Winston Churchill, who was then Home Secretary, came to take command of active operations, thereby causing an immense amount of ridicule in next day's papers. With a bowler hat pushed firmly down on his bulging brow, and one hand in his breast pocket, like Napoleon on the field of battle, he peered round the corner of the street, and afterwards, as we learned, ordered up some field guns to blow the house to bits."

The police were blamed for not bringing out the men alive. Churchill also came under attack from the foreign press. One German newspaper commented: "As for us, a thousand policeman, troops, firemen, and machine-guns, would never be necessary to capture a criminal in Berlin. Our police would also think it their business to take the criminals alive. The action of the London police is comparable to the shooting of sparrows with cannon." According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973), an early newsreel of Churchill directing the operations "was nightly received with unanimous boos and shouts of 'shoot him' from the gallery."

In the House of Commons the leader of the opposition, Arthur Balfour, joined in the widespread criticism of his behaviour: "He (Churchill) was, I understand, in a military phrase, in what is known as the zone of fire. He and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing. But what was the right honourable gentleman doing?" Churchill's biographer, Clive Ponting, commented: "His intervention attracted huge publicity and for the first time raised in public doubts about Churchill's character and judgement, which some of his colleagues had already had in private, and which were to increase in the next few years."

Cyril Morris, of the London Fire Brigade also criticised the way Churchill handled the situation and disagreed with his order to "Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders." Morris explained: "While being duly thankful for this order. I never can understand why the then Home Secretary took executive charge of a situation requiring the most careful handling as between the police and fire brigade. and as we shall see in a moment, he gave me a wrong order. Had I been a more experienced officer, I should have taken orders from nobody - advice from the police, yes, Under the conditions, but orders, definitely no."

Backlash against the Jewish Population

The Siege of Sidney Street created a backlash against the East End's Jewish community. The Morning Post compared the immigrants to "typhoid bacilli" and the area contained "aliens of the worse type - violent, cruel and dirty". Other newspapers said the British establishment was "in a state of denial" and that East End Jews had not "integrated" and a "threat to our security". The Daily Mail argued: "Even the most sentimental will feel that the time has come to stop the abuse of the country's hospitality by the foreign malefactors."

Winston Churchill later wrote in his memoirs: "We were clearly in the presence of a class of crime and a type of criminal which for generations had to counterpart in England. The ruthless ferocity of the criminals, their intelligence, their unerring marksmanship their modern weapons and equipment, all disclosed the characteristic of the Russian Anarchist."

King George V also became involved in the controversy and asked Churchill if "these outrages by foreigners will lead you to consider whether the Aliens Act could not be amended so as to prevent London from being infested with men and women whose presence would not be tolerated in any country". As the author of Winston Churchill (1994) has pointed out: "Within a fortnight of the siege Churchill circulated a draft Bill to the Cabinet to introduce harsh new laws against aliens. He had dropped a provision that he originally wanted giving the police the right to arrest any alien who had no obvious way of earning a living but had retained one that allowed an alien, if he could not find sureties for good behaviour, to be kept in prison until the Home Secretary, not the courts, was satisfied about his position."

Churchill described this power as "a fine piece of machinery". The Bill also contained what Churchill described to his colleagues as "two naughty principles" of making "a deliberate differentiation between the alien, and especially the unassimilated alien, and a British subject." This would give the Home Secretary the power to deport an alien merely on suspicion even though he had committed no criminal offence. The Bill was introduced into the House of Commons by Churchill at the end of April but MPs refused to pass such an illiberal measure and it had to be withdrawn.

Siege of Sidney Street Trial

On 23rd January, 1911, A. H. Bodkin, opened the case for the Crown against Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof and Nina Vassilleva. He made a major mistake in arguing that it was George Gardstein who had shot Robert Bentley and Charles Tucker: "Gardstein was the man who came in flinging open that back door and shot Bentley at his right front; there were also other shots from the man on the stairs.... Several shots were fired at Bentley by the man Gardstein from the back, he advanced to the front door of the house, of that there is no doubt, for we have the hand, according to the evidence of Strongman, protruding through the door of No. 11, so as to sweep the place, firing at Woodhams, Bryant and Martin."

Bodkin based his analysis on the discover of the Dreyse gun in Gardstein's room: "Now Gardstein - under his pillow at 59 Grove Street was found exhibit No. 2, which was a Dreyse pistol. A pistol with a magazine, which on examination had been recently fired. It is difficult to say - for any expert to say - when it had been recently fired. It was a pistol rifled in four grooves, and Mr Goodwin, a gentleman who has kindly examined this pistol... has fired some shots from that pistol into sawdust. The cartridges which can be fired from that pistol are quite common cartridges which are standardised and are used for various automatic pistols, but the peculiarity of this Dreyse pistol is that it has four grooves. It appears that six bullets - two from Tucker's body, two from Bentley's body and two from Choat's body - were fired from the Dreyse pistol as they all have four groove marks upon them.... It is clear that Gardstein was the man who fired, and under his pillow a Dreyse pistol was found, and it seems quite proper to assume that he it was who used the Dreyse pistol. The only one to hit Bentley was Gardstein, and Bentley's bullets were from a Dreyse pistol."

What the prosecuting counsel had difficulty explaining was the lack of Dreyse ammunition in Gardstein's house. As Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973) has pointed out: "Now it has been wrongly assumed from Mr Bodkin's statement that the pistol was under the pillow for Gardstein to defend himself and to resist arrest. In support of this theory it has been alleged that a cap containing a quantity of ammunition was placed by the bed within easy reach of his hand. Certainly there was a cap with ammunition by the bed but none of it could be fired from the Dreyse... If, in fact, Gardstein had owned the Dreyse, it is reasonable to suppose that some ammunition for this weapon would have been found in his lodgings, which were described as an arsenal as well as a bomb factory. None was found." Rumbelow goes on to argue that the only ammunition "consisted of ... 308 .30 Mauser cartridges, some of D.W.M. (German) manufacture, and the other with plain heads; also 26 Hirtenberger 7.9 mm Mauser rifle cartridges". Rumbelow adds that "it is inconceivable, surely, that a man would have over 300 rounds of ammunition for a Mauser pistol which he didn't possess, and none for the Dreyse he is supposed to have used!"

Rumbelow suggested that Yakov Peters had planted his Dreyse gun in the room when along with Yourka Dubof, Peter Piaktow and Fritz Svaars, he had taken Gardstein to 59 Grove Street. Peters realised that Gardstein was dying and that the police would eventually find his body. If they also found the gun that had done most of the killing, they would assume that Gardstein was the man responsible for the deaths of the three policemen.

The case was adjourned when another gang members were arrested in February, 1911. The trial of the Houndsditch murders opened at the Old Bailey on 1st May. Yakov Peters and Yourka Dubof were charged with murder. Peters, Dubof, Karl Hoffman, Max Smoller and John Rosen were charged with attempting to rob Henry Harris's jeweller's shop. Sara Trassjonsky and Nina Vassilleva, were charged with harbouring a felon guilty of murder.

The opening speech of A. H. Bodkin lasted two and a quarter hours. He argued that George Gardstein killed Robert Bentley, Charles Tucker and Walter Choat and Smoller shot Gardstein by mistake. Justice William Grantham was unimpressed with the evidence presented and directed the jury to say that the two men, against whom there was no evidence of shooting, were not guilty of murder. Grantham added that he believed that the policeman were killed by George Gardstein, Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. "There were three men firing shots and I think they are dead."

The prosecution's principal witness that linked Peters and Dubof to Gardstein was Isaac Levy, who saw the men drag him along Cutler Street. Levy came under a fierce attack from defence counsel. After his testimony, Justice Grantham said that if there was no other evidence of identification he could not allow any jury to find a verdict of guilty on Levy's uncorroborated statement. After Grantham's summing-up made it clear that none of the men should be convicted of breaking and entering, the jury found them all not guilty and they were set free.

Nina Vassilleva was found guilty of conspiracy to commit a robbery but recommended that she should not be deported. Vassilleva was sentenced to two years' imprisonment, but five weeks later the Court of Appeal quashed her conviction on the ground of misdirection of the jury by Justice Grantham (he was himself to die a few months later).

The Daily Mail reported on 13th May 1911. "Five months have passed since 16 December, when three constables of the City Police were murdered by a gang of armed alien burglars and two more policemen were seriously wounded. Not a single one of their assassins has been punished by the law. Gardstein, one of the murderers, was mortally wounded by a chance shot from one of his confederates. Two more of the gang perished in the Sidney Street battle of January. But it is certain that the persons implicated were numerous. It is no pleasant or satisfactory reflection that several of the principals in the crime and many of their associates have escaped and are still at large."

Was the Siege of Sidney Street a Government Conspiracy?

In 2009 Christopher Andrew published The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5. In the writing of the book he was given complete access to MI5 documents. He found evidence that the Peter the Painter gang was being monitored by MI5 in 1910. Vernon Kell, the head of MI5, described them as "a desperate and very dangerous crowd". Kell told the Home Office that the gang was "closely connected with the Houndsditch murders". The chief suspect was Yakov Peters. Why then did Peters get such an easy ride at the trial?

Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972), has argued that Joseph Stalin was in London at this time. He claims "James Burley, of Woodhouse, near Sheffield, recalls that in 1910 he was living in Soho, the Latin quarter of London, and that he spent a lot of time at the Continental Cafe in Little Newport Street, which was a centre of the Nihilist movement." Deacon quotes Burley as saying "The cafe was popular because it was only a short walk from the Communist Club in Charlotte Street. Josef Stalin used the Continental Cafe a lot. Josef Georgi he called himself. He was a bombastic little man, not very big. But there was always an air of mystery about him." Burley believes that Stalin was involved in the planning the Houndsditch robbery: "He was looked up to as one of the leaders and I'm sure he had a hand in planning the burglary which was the cause of the police investigations in the first place. Stalin was the leader of the group and it was he who was keeping a close watch on the mystery figure known as Peter the Painter."

It is true that Stalin did organize bank robberies in Russia to help fund Bolshevik political activities. Stalin was also in London to attend the Party Congress in April 1907. According to Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004): "In April 1907... Stalin joined the mass of delegates in the East End, Jewish immigrant families from the Russian Empire lived there in their thousands at the turn of the century (and, like the Irish, were a substantial minority). This was the best spot for delegates to avoid attention from the Special Branch."

However, after the conference, he returned to Russia and became involved in revolutionary activity in Baku. Stalin later wrote: "Two years of revolutionary work among the oil workers of Baku hardened me as a practical fighter and as one of the practical leaders. In contrast with advanced workers of Baku... in the storm of the deepest conflicts between workers and oil industrialists... I first learned what it meant to lead big masses of workers. There in Baku... I received my revolutionary baptism in combat." However, he was caught by the Okhrana and put in prison. In November 1908 Stalin and Gregory Ordzhonikidze were deported to Solvychegodsk, in the northern part of the Vologda province on the Vychegda River. He remained there during the Houndsditch Murders and the Siege of Sidney Street and did not escape until 1912.

Although Joseph Stalin was not in London at the time he, or some other senior figure in the Bolsheviks might have been controlling the Peter the Painter gang. Despite the claims that the men were anarchists, they were in fact Bolsheviks. In fact, after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, Yakov Peters returned to Russia and took part in the successful Russian Revolution. Three months later he was appointed deputy to Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka). In one month in 1919, Peters sentenced 400 anarchists to death. He boasted that in the first year the Cheka shot only 6,000 people but that was because they were too inexperienced.

In A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972), Richard Deacon gives another reason why the Russians were not convicted of crimes they had clearly committed in 1910. Deacon argues that Gerald Bullett investigated the Sidney Street affair in some detail, stated that there was a "certain amount of corroborative evidence that Peter the Painter so far from being the leader of the gang was in fact an agent of the Russian Government, entrusted with the delicate and dangerous task of posing as a comrade of the anti-Tsarist conspirators, and of persuading them to engage in criminal activities such as housebreaking, which would attract to them the attention of the London police and ensure their ultimate deportation to Russia."

The use of agent provocateurs was a common tactic used by the Okhrana, the Russian secret police, during this period. However, why would the British government do as much as it did to cover this up? They would of course do this if their own intelligence service was employing a similar tactic. We now know that MI5 were very well informed about the activities of Russian revolutionaries in London. Is it possible that Yakov Peters was working as an agent provocateur for MI5? Was he promised his freedom in exchange for his silence during the trial?

If this was the case, it helps to explain Winston Churchill's behaviour during the Siege of Sidney Street. The Daily Telegraph reported on the day after these dramatic events: "Yesterday a scene unparalleled in the history of English civilisation was witnessed in the very heart of one of the most congested parts of the East End of London. For about four hours what amounted to a pitched battle was waged between about 1,000 armed police and military and two or three Anarchists who are believed to have been connected with the Houndsditch outrage of three weeks ago."

There is no doubt that this dramatic event did result in newspapers calling for an end to immigration. Winston Churchill did what he could by introducing harsh new laws against aliens but these were rejected by the House of Commons. However, this was not an end to the matter. On the outbreak of the First World War Parliament passed the 1914 Aliens Restriction Act. The primary aim of the 1914 Act was to target "enemy aliens" resident in Britain during the war.

At the end of the war the government passed the 1919 Aliens Restriction Act. This continued these restrictions into peace-time and extended them. It restricted the employment rights of aliens resident in Britain, barring them from certain jobs (in the civil service, for example), and had a particular impact on foreign seamen working on British ships. It also targeted criminals, paupers and ‘undesirables’, and made it illegal for aliens to promote industrial action. As one historian has pointed out, this act "ended mass immigration to England for more than three decades."

The Death of Yakov Peters

Yakov Peters was made Chief of Internal Defence and on 14th June 1919 Pravda printed an order by Peters that the wives and grown-up children of all officers escaping to the anti-Bolshevik ranks should be arrested. The following day he ordered the disconnection of all private telephones in Petrograd and the confiscation of all wine, spirits, money above £500 and jewels. In Petrograd he insisted that all citizens had to carry identity cards issued by Cheka. He also had three thousand hostages transported to Moscow.

Arthur Ransome was a journalist working in Petrograd who got to know Peters during this period. He described him as being "a small man with a square forehead, very dark eyes and a quick expression... he speaks fair English, though he is gradually forgetting it. He knows far less now than a year ago." Ransome enjoyed the company of Peters and described him as a man of "scrupulous honesty". Peters told Ransome that his methods was keeping crime under control: "We have now shot eight robbers, and we posted the fact at every street corner, and there will be no more robbery. I have now got such a terrible name that if I put up a notice that people will be dealt with severely that is enough, and there is no need to shoot anybody."

Lenin defended the work of Peters and Cheka by publicly stating: "What surprises me about the howls over the Cheka's mistakes is the inability to take a large view of the question. We have people who seize on particular mistakes by the Cheka, sob and fuss over them... When I consider the Cheka's activity and compare it with these attacks, I say this is narrow-minded, idle talk which is worth nothing... When we are reproached with cruelty, we wonder how people can forget the most elementary Marxism.... The important thing for us to remember is that the Chekas are directly carrying out the dictatorship of the proletariat, and in this respect their role is invaluable."

Peters went on to loyally serve Joseph Stalin: During the Red Terror it is claimed by Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972): "Peters conducted interrogations daily and when he was not engaged in this work he was furiously signing death warrants, often not looking to see what he was signing. During one visit a visitor from a neutral country noticed that Peters signed an order to shoot seventy-two officers without even glancing down at the paper. His amiability had gone and he snapped out his replies to questions." One source heard him say "I am so tired I cannot think. I am worn out signing orders for executions." In his book Deacon goes onto defend Peters: "But to portray Peters solely as a monster is to give a one-sided picture of the man. He was a dispassionate operator, dedicated more to efficiency and speed than to sadism. He was quite unlike some of the animalistic executioners of the Terror: he took no pleasure in his grim work and indeed he often berated his men for prolonging torture and death as a needless waste of time. Those who knew him testified to many small kindnesses which he performed when off duty: he delighted in speaking English on every possible occasion and, in fact, his pro-British and pro-American prejudices caused suspicion among his colleagues."

In 1937 Stalin ordered the arrest of a large number of Bolsheviks who were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. This included Yakov Peters, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky. Peters was executed on this trumped up charge on 25th April, 1938. It was over 27 years since he had murdered three brave London policeman, Robert Bentley, Charles Tucker and Walter Choat.

Primary Sources

(1) Donald Rumbelow, The Siege of Sidney Street (1973)

Bentley stepped further into the room. As he did so the back door was flung open and a man, mistakenly identified as Gardstein, walked rapidly into the room. He was holding a pistol which he fired as he advanced with the barrel pointing towards the unarmed Bentley. As he opened fire so did the man on the stairs. The shot fired from the stairs went through the rim of Bentley's helmet, across his face and out through the shutter behind him. 'Gardstein' by now had closed to within three or four feet and was firing just across the table. At point-blank range he could not miss. His first shot hit Bentley in the shoulder and the second went through his neck almost severing his spinal cord. Bentley staggered back against the half-open door and collapsed backwards over the doorstep so that he was lying half in and half out of the house. Bryant, who had been standing partly behind him, glimpsed the pistol turning towards him and put out his hands instinctively, as he said later, "to ward off the flashes". He felt his left hand fall to his side and then, stumbling over the dying Bentley, he fell into the street. He had only a hazy recollection of what followed but he remembered getting up and staggering along the pavement. Fortunately he walked away from the entrance to the cul-de-sac, which probably saved his life. He was very dazed and fell down again. He regained consciousness some minutes later and found himself propped up against the wall of one of the houses. He had been shot in the arm and slightly wounded in the chest.

Constable Woodhams saw Bentley fall backwards over the doorstep and ran to help him. He could not see who was doing the shooting. Suddenly his leg buckled beneath him as a Mauser bullet shattered his thigh bone and he fell unconscious to the ground. Constable Strongman and Sergeant Tucker saw him fall but neither could see who was doing the shooting. Only a hand clutching a pistol protruded from the doorway. "The hand was followed by a man aged about 30, height 5 ft 6 or 7, pale thin face, dark curly hair and dark moustache, dress dark jacket suit, no hat, who pointed the revolver in the direction of Sergeant Tucker and myself, firing rapidly. P. S. Tucker and I stepped back a few yards, when the sergeant staggered and turned round.' Strongman caught him by the arm and Tucker staggered the length of the cul-de-sac before collapsing in the roadway. He had been shot twice, once in the hip and once in the heart. He died almost instantly.

Martin, who like Strongman was in plain clothes, had been standing by the open door when the shooting started. As Bentley then Bryant staggered back bleeding from gun wounds, he turned and ran for the partly open door behind him. Bessie Jacobs' first thought when she heard the opening shots was that the high wind had blown the chimney pot off. But then she saw the gun flashes through the tops of the shutters. She pulled her nightclothes tighter round her and as she reached the door it burst open and Martin leaped inside. He slammed the door behind him as she began to scream. He covered her mouth with his hand. `Don't scream, I'm a detective,' he pleaded. `I'll protect your mother and I'll protect you.'

In the darkness, some of the targets were little more than shadows, and bullets splintered and gouged the wooden fronts of the houses as the gang raced for the entrance. Twenty-two shots were fired. Gardstein had almost reached the entrance when Constable Choat caught hold of him by the wrist and fought him for possession of his gun. As Gardstein pulled the trigger repeatedly Choat desperately pushed the pistol away from the centre of his body and the shots were fired into his left leg. Others of the gang rushed to Gardstein's assistance and turned their guns on Choat. He was a big, muscular man, 6 feet q4 inches tall, and in spite of the darkness a target impossible to miss. He was shot five more times. The last two bullets were fired into his back. As he fell backwards he dragged Gardstein with him and a shot, fired at Choat, hit Gardstein in the back. Choat was kicked in the face to make him release his

grip on Gardstein, who was seized by two of the group and dragged away. But already he was a dying man.

(2) Solomon Abrahams, statement (17th December, 1910)

I heard a smash of glass at No. 11. A man then opened the door, I did not see his face, I only saw his arm and heard a report of a firearm and immediately saw the policeman fall into the doorway. A man then ran out of the door with a revolver in his hand and fired about eight shots at the officers and four of them fell. Sergeant Bentley ran towards the man and caught hold of him by the shoulders and threw him to the ground. The man caught hold of the Sergeant's legs and pulled him down. They struggled and the man got on top of P.C. Bentley. Another man, whom I cannot describe, ran out of No 11 and fired at Bentley, the bullet struck the man in the back and he fell backwards with his arms up in the air. I then went inside my house where I remained until the firing ceased. I heard about 15 shots fired in quick succession.

(3) The Daily Telegraph (17th December, 1910)

Some two or three weeks ago this particular house in Exchange Buildings was rented and there went to live there two men and a woman. They were little known by neighbours, and kept very quiet, as if, indeed, to escape observation. They are said to have been foreigners in appearance, and the whole neighbourhood of Houndsditch containing a great number of aliens, and removal being not infrequent, the arrival of this new household created no comment.

The police, however, evidently had some cause to suspect their intentions. The neighbourhood is always well patrolled. Shortly before 11.30 last night there were sounds either at the back of these newcomers' premises or at Mr Harris's shop that attracted the attention of the police.

(4) The Daily Chronicle (18th December, 1910)

The street door opens into a narrow and ill-lighted passage, in which badly washed and ragged clothing was hanging from bits of string. Towards the end of the passage a sharp turn to the left led me on to a narrow and almost perpendicular staircase, without handrail. Here was more washing suspended from the ceiling. At the top of a staircase was a small landing, and immediately in front was the room in which the assassin died.

The room itself is about ten feet by nine, and about seven feet high. A gaudy paper decorates the walls and two or three cheap theatrical prints are pinned up. A narrow iron bedstead painted green, with a peculiarly shaped head and foot faces the door. On the bedstead was a torn and dirty woollen mattress, a quantity of blood-stained clothing, a blood-stained pillow and several towels also saturated with blood.

Under the window stood a string sewing machine, and a rickety table, covered with a piece of mole cloth, occupied the centre of the room. On it stood a cup and plate, a broken glass, a knife and fork, and a couple of bottles and a medicine bottle. Strangely contrasting with the dirt and squalor, a painted wooden sword lay on the table, and another, to which was attached a belt of silver paper, lay on a broken desk supported on a stool. On the mantelpiece and on a cheap whatnot stood tawdry ornaments. In an open cupboard beside the fireplace were a few more pieces of crockery, a tin or two, and a small piece of bread. A mean and torn blind and a strip of curtain protected the window, and a roll of surgeon's lint on the desk. The floor was bare and dirty, and, like the fireplace, littered with burnt matches and cigarette ends - altogether a dismal and wretched place to which the wounded desperado had been carried to die.

(5) Fritz Svaars, letter to George Gardstein (undated)

All around I see awful things which I cannot tell you. I do not blame our friends as they are doing all that is possible, but things are not getting better.

The life of the workman is full of pain and suffering, but if the suffering reaches a certain degree one wonders whether it would not be better to follow the example of Rainis (an author of Lettish poems) who says burn at once so that you may not suffer long, but one feels that one cannot do it although it seems very advisable. The outlook is always the same, awful outlook for which we must sacrifice our strength. There is not and cannot be another outlet. Under such circumstances, our better feelings are at war with those who live upon our labour. The weakest part of our organisation is that we cannot do sufficient for our friends who are falling. For instance, such an incident occurred last week. I had to send 10 roubles to Milan Prison for S. German who is to be transferred to another prison. I also had to secure the necessary for Krustmadi, and this evening I received news from Libau prison that one of our friends of last summer has been taken there without any money. We ought to help but we have only 33 kopecks and the treasury of the Red X is quite empty. It is terrible because the prisoner may think we will not help him!

(6) The Daily Telegraph (27th December, 1910)

Anarchist literature, in sufficient quantities to corroborate the suspicion of the police that they are face to face with a far-reaching conspiracy, rather than an isolated and unpremeditated attack on civil authority, is stated to have been recovered.

It is reported, in addition, that a dagger was found and a belt, which is understood to have had placed within it 150 Mauser dumdum bullets - bullets, that is, with soft heads, which, upon striking a human body, would spread and inflict a wound of a grievous, if not fatal character.

(7) Superintendent Mulvaney, statement (4th January, 1911)

The measurements of the passage and staircase will show how futile any attempt to storm or rush the place would have been, with two men... dominating the position from the head of the stairs and where, to an extent, they were well under cover from fire. The passage at one discharge would have been blocked by fallen men; had any even reached the stairs, it could only have been by climbing over the bodies of their comrades, when they would stand little chance of getting further; had they even done this the two desperadoes could retreat up the staircase to the first and second storey, on each of which, what had occurred below would have been repeated.

(8) Cyril Morris, Fire! On the work of the London and other Fire Brigades (1939)

As I arrived at the fire. I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen - thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must he there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house. from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols.

I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations. His order to me was 'Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders.' While being duly thankful for this order. I never can understand why the then Home Secretary took executive charge of a situation requiring the most careful handling as between the police and fire brigade. and as we shall see in a moment, he gave me a wrong order.

Had I been a more experienced officer, I should have taken orders from nobody - advice from the police, yes, Under the conditions, but orders, definitely no. At a Fire in London the Chief Officer of thc LFB or his representative

is granted by Act of Parliament absolutely full plenary powers. There can be no officer who has such a wide authority under normal peacetime conditions, and this authority is very necessary at times when immediate decisions have to he made involving the protection of' perhaps millions pounds worth of property.After receiving this order I took stock of the position. The front rooms on the first and second floors were starting to emit dense clouds of smoke, which shortly turned to flames. The firing from the house was gradually ceasing. Shortly afterwards the flames reached the roofs, which blazed up, the fire spreading to the adjoining roofs, this being one of a row of terraced houses. By this time we in the Brigade were to say the least getting somewhat restless. How far would the fire spread before we could start to attack it? The LFB Superintendent kept urging me to do something, but the Home Secretary was a very important dignitary to a junior officer, so I sat tight while the fire continued to spread.

The houses all had a projecting back addition containing two rooms. As the front windows had been broken by shots before the fire started. the draft from the fire had carried it to the front and in all probability the back two rooms were intact. No sooner had we realised what we might he up against - a burst of firing from the back of the house as soon as we approached it - than the order came "You can now approach the fire."

So up we dashed with our lines of hose, through adjoining property to the back of the house followed by Mr. Wensley of the Metropolitan Police and we found the rooms absolutely intact, not even filled with smoke. Fortunately by that time the criminals were no longer in a position to fire on us. As we made our way through the back of the house the order was given to turn on the water.

While our party approached the back, another hose line was taken along the side of the street, up an adjoining house and on to the roof to attack the fire from above. By this time the house was well alight. The fire had travelled right down to the ground floor and the roofs of the houses on each sided had caught. In a few minutes the fire would have spread right along Sidney Street along both sides of the house we were attacking...

We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas.

(9) Philip Gibbs, Adventures in Journalism (1923)

For some reason, which I have forgotten, I went very early that morning to the Chronicle office, and was greeted by the news editor with the statement that a hell of a battle was raging in Sidney Street. He advised me to go and look at it.

I took a taxi, and drove to the corner of that street, where I found a dense crowd observing the affair as far as they dared peer round the angle of the walls from adjoining streets. Heedless at the moment of danger, which seemed to ridiculous, I stood boldly opposite Sidney Street and looked down its length of houses. Immediately in front of me four soldiers of one of the Guards' regiments lay on their stomachs, protected from the dirt of the road by newspaper "sandwich" boards, firing their rifles at a house halfway down the street. Another young Guardsman, leaning against a wall, took random shots at intervals while he smoked a Woodbine. As I stood near he winked and said, "What a game."

It was something more than a game. Bullets were flicking off the walls like plugging holes into the dirty yellow brick, and ricocheting fantastically. One of them took a neat chip out of a policeman's helmet, and he turned, and he said, "Well, I'll be blowed!" and laughed in a foolish way...

It was a good vantage point (on the roof of the "The Rising Sun"), as we should have called it later in history. It looked right across to the house in Sidney Street in which Peter the Painter and his friends were defending themselves to the death - a tall, thin house of three storeys, with dirty window blinds. In the house immediately opposite were some more Guardsmen, with pillows and mattresses stuffed into the windows in the nature of sandbags as used in trench warfare. We could not see the soldiers, but we could see the effect of their intermittent fire, which had smashed every pane of glass and kept chipping off bits of brick in the anarchists' abode.

The street had been cleared of all onlookers, but a group of detectives slunk along the walls on the anarchists' side of the street at such an angle that they were safe from the slanting fire of the enemy. They had to keep very close to the wall, because Peter and his pals were dead shots and maintained something like a barrage fire with their automatics. Any detective or policeman who showed himself would have been sniped in a second, and these men were out to kill.

The thing became a bore as I watched it for an hour or more, during which time Mr Winston Churchill, who was then Home Secretary, came to take command of active operations, thereby causing an immense amount of ridicule in next day's papers. With a bowler hat pushed firmly down on his bulging brow, and one hand in his breast pocket, like Napoleon on the field of battle, he peered round the corner of the street, and afterwards, as we learned, ordered up some field guns to blow the house to bits.That never happened for a reason which we on "The Rising Sun" were quick to see.

In the top-floor room of the anarchists' house we observed a gas jet burning, and presently some of us noticed the white ash of burnt paper fluttering out of a chimney pot.

"They're burning documents," said one of my friends.

They were burning more than that. They were setting fire to the house, upstairs and downstairs. The window curtains were first to catch alight, then volumes of black smoke, through which little tongues of flame licked up, poured through the empty window frames. They must have used paraffin to help the progress of the fire, for the whole house was burning with amazing rapidity.

"Did you ever see such a game in London!" exclaimed the man next to me on the roof of the public house.

For a moment I thought I saw one of the murderers standing on the window sill. But it was a blackened curtain which suddenly blew outside the window frame and dangled on the sill.

A moment later I had one quick glimpse of a man's arm with a pistol in his hand. He fired and there was a quick flash. At the same moment a volley of shots rang out from the Guardsmen opposite. It is certain that they killed the man who had shown himself, for afterwards they found his body (or a bit of it) with a bullet through the skull. It was not long afterwards that the roof fell in with an upward rush of flame and sparks. The inside of the house from top to bottom was a furnace.

The detectives, with revolvers ready, now advanced in Indian file. One of them ran forward and kicked at the front door. It fell in, and a sheet of flame leaped out. No other shot was fired from within. Peter the Painter and his fellow bandits were charred cinders in the bonfire they had made.

(10) The Daily Chronicle (January, 1911)

At both ends of Sidney Street the Scots Guards were in position, taking cover behind the angle of the houses. Around them were groups of policemen in uniform armed with shot-guns, and numbers of plain clothes detectives with heavy revolvers. In the shadow of doorways and archways men crouched down with barrels of rifles and pistols pointed towards the house next to the doctor's surgery, with its shattered window-panes and broken brickwork. Looking down into the backyards of the houses opposite Martins Buildings, I could see soldiers and armed policemen moving about, climbing over fences, and getting up tall ladders, so that they could fire between the chimney pots.

On the roof of a great brewery on the same side of the way as the Rising Sun public-house were scores of the work people, and as far as the eye could see across the sloping roofs, the chimney-pots and parapets, the sky-line was black with heads, while in the streets below, as far as a quarter of a mile away, there were vast and tumultuous crowds, kept back by lines of mounted policemen. The voices of those many thousands came up to me in great murderous gusts, like the roar of wild beasts in a jungle. It seemed as if the whole of London had poured into Whitechapel and Stepney to watch one of the most deadly and thrilling dramas that has ever happened in the great city within living memory.

But my eyes were now fixed upon one building, and no other impression could find a place in my mind. The anarchists' had the horrible fascination of a house of death. Bullets were raining upon it. As I looked I saw how they spat at the walls, how they ripped splinters from the door, how they made neat grooves as they burrowed into the red bricks, or chipped off corners of them. The noise of battle was tremendous and almost continuous. The heavy barking reports of Army rifles were followed by the sharp and lighter cracks of pistol shots. Some of the weapons had a shrill singing noise, and others were like children's pop guns. Most terrible and deadly in sound was the rapid fire of the Scots Guards, shot speeding on shot, as though a Gatling gun were at work. Then there would come a sudden lull, as though a bugle had sounded "Cease fire", followed by a silence, intense and strange, after the ear-splitting din.

It reopened again when a few moments later there came the spitting fire of an automatic pistol from the house next to the surgery. From my vantage point I could see how the assassins changed the position from which they fired. The idea that only two men were concealed within that arsenal seemed disproved by the extreme rapidity with which their shots came from one floor and another. As I watched, gripped by the horror and drama of it, I saw a sharp stabbing flash break through the garret window. The man's weapon must have been over the edge of the window-sill. He emptied his magazine, spitting out the shots at the house opposite, from which picked marksmen of the Scots Guards replied with instant volleys. A minute later by my watch shots began to pour through the second floor window, and before the echo of them had died away there was a fusillade from the ground floor.So this amazing duel went on, as a distinct clock chimed the quarters and half hours. From 11 o'clock until 12.30 there were not scores or hundreds of shots fired, but thousands. It seemed that the assassins had an almost inexhaustible supply of ammunition.... Blazing timbers were flung into the street, masses of masonry crashed down, fiery splinters, like shooting stars, were hurtled a hundred yards or more. Broken glass fell upon the pavement again and again with a dreadful sound of destruction. And into all this turmoil and fury there poured a terrific artillery of shots. The soldiers were volleying now from every window and every roof on the opposite side of Sidney Street, and their shots had thunderous echoes, for other soldiers and many police were firing into the back of the blazing house from the yard.

(11) A. H. Bodkin, Q. C., statement (23rd January, 1911)

Gardstein was the man who came in flinging open that back door and shot Bentley at his right front; there were also other shots from the man on the stairs.... Several shots were fired at Bentley by the man Gardstein from the back, he advanced to the front door of the house, of that there is no doubt, for we have the hand, according to the evidence of Strongman, protruding through the door of No. 11, so as to sweep the place, firing at Woodhams, Bryant and Martin. That man Gardstein advanced further, for you will remember in the evidence of Strongman he said he came out and fired at him and Sergeant Tucker while they were in the roadway of Exchange Buildings....

Now Gardstein - under his pillow at 59 Grove Street was found exhibit No. 2, which was a Dreyse pistol. A pistol with a magazine, which on examination had been recently fired. It is difficult to say - for any expert to say - when it had been recently fired. It was a pistol rifled in four grooves, and Mr Goodwin, a gentleman who has kindly examined this pistol... has fired some shots from that pistol into sawdust.The cartridges which can be fired from that pistol are quite common cartridges which are standardised and are used for various automatic pistols, but the peculiarity of this Dreyse pistol is that it has four grooves. It appears that six bullets - two from Tucker's body, two from Bentley's body and two from Choat's body - were fired from the Dreyse pistol as they all have four groove marks upon them.... It is clear that Gardstein was the man who fired, and under his pillow a Dreyse pistol was found, and it seems quite proper to assume that he it was who used the Dreyse pistol. The only one to hit Bentley was Gardstein, and Bentley's bullets were from a Dreyse pistol.

(12) Sergeant Bryant, statement (January, 1911)

Immediately I saw a man coming from the back door of the room between Bentley and the table. On 6 January I went to the City of London Mortuary and there saw a dead body and I recognised the man. I noticed he had a pistol in his hand, and at once commenced to fire towards Bentley's right shoulder. He was just in the room. The shots were fired very rapidly. I distinctly heard 3 or 4. I at once put up my hands and I felt my left hand fall and I fell out on to the footway. Immediately the man commenced to fire Bentley staggered back against the door post of the opening into the room. The appearance of the pistol struck me as being a long one. I think I should know a similar one again if I saw it. Only one barrel, and it seemed to me to be a black one. I next remember getting up and staggered along by the wall for a few yards until I recovered myself. I was going away from Cutler Street. I must have been dazed as I have a very faint recollection of what happened then....

(13) Arthur Strongman, statement (January, 1911)

The door was opened by some person whom I did not see. P.S. Bentley appeared to have a conversation with the person, and the door was then partly closed, shortly afterwards P.S. Bentley pushed the door open and entered, about a minute later I heard several shots and saw P.S. Bentley fall from the doorway across the step. Other shots followed in quick succession and a hand holding a revolver, firing rapidly, protruded from the doorway of No. 11 Exchange Buildings and was pointed at P.C. Woodhams who I saw fall forward into the carriageway. That hand was followed by a man age about 30, height 5' 6" or 7", pale thin face, dark curly hair, and dark moustache, dress dark jacket suit, no hat, who pointed the revolver in the direction of P.S. Tucker and myself, firing rapidly. P.S. Tucker and I stepped back a few yards when the P.S. staggered and turned round. I caught him by the right arm, and we walked towards Cutler Street. I looked over my left shoulder and saw the man fire two more shots in our direction, then he turned and went back in the direction of No. I i Exchange Buildings. The whole of the shooting appeared to be over in ten seconds.

In court he expanded on some details. He was standing with Sergeant Tucker when I heard 3 or 4 shots fired, and we made a step towards the door, when I saw a hand holding a pistol protrude from the street doorway of No. 11, firing rapidly, pointing towards P.C. Woodhams, who was opposite No. 11 Exchange Buildings. I saw P.C. Woodhams fall towards the carriageway; this man came out of the doorway still holding the pistol and pointed it towards Sergeant Tucker and myself, firing rapidly all the time. We stepped back, Sergeant Tucker turned round and staggered. Seeing he was wounded I put my arm round his and led him towards Cutler Street. I looked over my left shoulder and saw the man fire two more shots in our direction, and I could also see the flashes coming from the doorway of No. 11. He turned and went back in the direction of No. 11.... I could only see the barrel as he came under the lamp and it looked a long thin one. The shooting only lasted about 10 seconds and may have been less.

(14) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

It is not generally known that Stalin himself was involved in Bolshevik activities in London and that he paid surreptitious visits to that city under the name of Josef Georgi. Indeed, Stalin, as much as anyone, was a leading figure behind the scenes in the affair of the Siege of Sidney Street in 1910.

This incident which resulted in a five-hour rifle battle between Anarchists and Scots Guards provided an excellent example of Russian counter-espionage techniques as used abroad. A police sergeant, investigating a report of "strange noises" coming from a house in Sidney Street, Houndsditch, called there and was shot dead. When other police surrounded the house and demanded that the occupants surrendered they were met by a barrage of fire from automatic pistols. Two more police were shot dead and Winston Churchill, then the Home Secretary, ordered out the Scots Guards to assist the police. One thousand police, supported by the Guards, kept up a fire on the house, which was eventually burnt down.

It was established afterwards that the "Sidney Street Gang", as they became known, were recruited from a small colony of about twenty Letts from Baltic Russia, but the identity of their leader was never officially confirmed. This mysterious character was known as "Peter the Painter" and long afterwards the Soviet Government alleged that he was Serge Makharoff, the Czarist agent provocateur.

But was he? There are varying points of view. Mr. James Burley, of Woodhouse, near Sheffield, recalls that in 1910 he was living in Soho, the Latin quarter of London, and that he spent a lot of time at the Continental Cafe in Little Newport Street, which was a centre of the Nihilist movement. "The cafe was popular," states Mr. Burley, "because it was only a short walk from the Communist Club in Charlotte Street. Josef Stalin used the Continental Cafe a lot. Josef Georgi he called himself. He was a bombastic little man, not very big. But there was always an air of mystery about him."

Mr. Burley claimed that Stalin knew all about the events which led up to the Sidney Street affair several days before it happened. "He was looked up to as one of the leaders and I'm sure he had a hand in planning the burglary which was the cause of the police investigations in the first place. Stalin was the leader of the group and it was he who was keeping a close watch on the mystery figure known as "Peter the Painter."

Stalin returned to Russia shortly afterwards and it may be that he was keeping "Peter the Painter" under surveillance, or that he actually aided and abetted his escape. Gerald Bullett, who investigated the Sidney Street affair in some detail, stated that there was a "certain amount of corroborative evidence that Peter the Painter so far from being the leader of the gang was in fact an agent of the Russian Government, entrusted with the delicate and dangerous task of posing as a comrade of the anti-Tsarist conspirators, and of persuading them to engage in criminal activities such as housebreaking, which would attract to them the attention of the London police and ensure their ultimate deportation to Russia.

"This, I think, is by far the likeliest explanation of the mystery of Peter the Painter.... In all probability it was Peter the Painter, agent provocateur, employed by the police of Tsarist Russia, who by elaborate trickery encompassed the defeat and dispersal of the Houndsditch murderers. It was at his instigation, I suggest, that the jewel robbery was planned."

The reference to the "jewel robbery" is explained by the fact that the immediate cause of the Sidney Street siege was the planning of the burglary of a jeweller's shop in Houndsditch. An ex-officer of the Ochrana had stated that the jeweller in question had been entrusted with the safe custody of treasure belonging to the Romanoffs. That this statement was a distortion of the facts is more than likely. This is the kind of story a Czarist agent would be likely to invent to incite the revolutionaries to burgle the jeweller's premises.

(15) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994)