Fritz Svaars

Fritz Svaars was born in Russia in about 1886. He was the cousin of Yakov Peters.

Svaars took part in the 1905 Russian Revolution and in October was arrested in Riga with four others on suspicion of tearing down telephone wires, robbing two state-owned shops and the administration offices at Pormsaten. He was also charged with killing a policeman and a shopkeeper. A few days later he escaped from his place of detention in Grabin.

After working as a sailor he arrived in London in 1908. According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "He spoke English and German imperfectly. He was square-shouldered with light-brown hair and a turned-up moustache which partly concealed the few small pimples or smallpox scars on his face. His eyes were grey, and he hunched his shoulders slightly when he walked. His clothes were American style."

Svaars associated with fellow Russian revolutionaries such as Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), Yakov Peters, George Gardstein, Yourka Dubof, Karl Hoffman, John Rosen, Max Smoller and William Sokolow. He then returned to Riga but in January 1910 he was arrested by Okhrana, the Russian secret police. However, he managed to escape and returned to London in June 1910. Soon afterwards he met Luba Milstein who fell in love with him. Svaars told her that he was a married man and planning to emigrate to Australia with his wife.

Fritz Svaars and the Peter the Painter Gang

On 16th December 1910, a gang that is believed to include Svaars, Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), Yakov Peters, George Gardstein, Yourka Dubof, Karl Hoffman, John Rosen, Max Smoller and William Sokolow, attempted to break into the rear of Henry Harris's jeweller's shop in Houndsditch, from 11 Exchange Buildings in the cul-de-sac behind. The Daily Telegraph reported: "Some two or three weeks ago this particular house in Exchange Buildings was rented and there went to live there two men and a woman. They were little known by neighbours, and kept very quiet, as if, indeed, to escape observation. They are said to have been foreigners in appearance, and the whole neighbourhood of Houndsditch containing a great number of aliens, and removal being not infrequent, the arrival of this new household created no comment. The police, however, evidently had some cause to suspect their intentions. The neighbourhood is always well patrolled. Shortly before 11.30 last night there were sounds either at the back of these newcomers' premises or at Mr Harris's shop that attracted the attention of the police."

A neighbouring shopkeeper, Max Weil, heard their hammering, informed the City of London Police, and nine unarmed officers arrived at the house. Sergeant Robert Bentley knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings. The door was open by Gardstein and Bentley asked him: "Have you been working or knocking about inside?" Bentley did not answer him and withdrew inside the room. Bentley gently pushed open the door, and was followed by Sergeant Bryant. Constable Arthur Strongman was waiting outside. "The door was opened by some person whom I did not see. Police Sergeant Bentley appeared to have a conversation with the person, and the door was then partly closed, shortly afterwards Bentley pushed the door open and entered."

The Houndsditch Murders

According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "Bentley stepped further into the room. As he did so the back door was flung open and a man, mistakenly identified as Gardstein, walked rapidly into the room. He was holding a pistol which he fired as he advanced with the barrel pointing towards the unarmed Bentley. As he opened fire so did the man on the stairs. The shot fired from the stairs went through the rim of Bentley's helmet, across his face and out through the shutter behind him... His first shot hit Bentley in the shoulder and the second went through his neck almost severing his spinal cord. Bentley staggered back against the half-open door and collapsed backwards over the doorstep so that he was lying half in and half out of the house."

Sergeant Bryant later recalled: "Immediately I saw a man coming from the back door of the room between Bentley and the table. On 6 January I went to the City of London Mortuary and there saw a dead body and I recognised the man. I noticed he had a pistol in his hand, and at once commenced to fire towards Bentley's right shoulder. He was just in the room. The shots were fired very rapidly. I distinctly heard 3 or 4. I at once put up my hands and I felt my left hand fall and I fell out on to the footway. Immediately the man commenced to fire Bentley staggered back against the door post of the opening into the room. The appearance of the pistol struck me as being a long one. I think I should know a similar one again if I saw it. Only one barrel, and it seemed to me to be a black one. I next remember getting up and staggered along by the wall for a few yards until I recovered myself. I was going away from Cutler Street. I must have been dazed as I have a very faint recollection of what happened then."

Constable Ernest Woodhams ran to help Bentley and Bryant. He was immediately shot by one of the gunman. The Mauser bullet shattered his thigh bone and he fell unconscious to the ground. Two men with guns came from inside the house. Strongman later recalled: "A man aged about 30, height 5 ft 6 or 7, pale thin face, dark curly hair and dark moustache, dress dark jacket suit, no hat, who pointed the revolver in the direction of Sergeant Tucker and myself, firing rapidly. Strongman was shot in the arm, but Sergeant Charles Tucker was shot twice, once in the hip and once in the heart. He died almost instantly.

The Death of George Gardstein

As George Gardstein left the house he was tackled by Constable Walter Choat who grabbed him by the wrist and fought him for possession of his gun. Gardstein pulled the trigger repeatedly and the bullets entered his left leg. Choat, who was a big, muscular man, 6 feet 4 inches tall, managed to hold onto Gardstein. Other members of the gang rushed to his Gardstein's assistance and turned their guns on Choat and he was shot five more times. One of these bullets hit Gardstein in the back. The men pulled Choat from Gardstein and carried him from the scene of the crime.

Fritz Svaars, Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof and Peter Piaktow, half dragged and half carried Gardstein along Cutler Street. Isaac Levy, a tobacconist, nearly collided with them. Peters and Dubof lifted their guns and pointed them at Levy's face and so he let them pass. For the next half-hour they were able to drag the badly wounded man through the East End back streets to 59 Grove Street. Max Smoller and Nina Vassilleva, went to a doctor who they thought might help. He refused and threatened to tell the police.

They eventually persuaded Dr. John Scanlon, to treat Gardstein. He discovered that Gardstein had a bullet lodged in the front of the chest. Scanlon asked Gardstein what had happened. He claimed that he had been shot by accident by a friend. However, he refused to be taken to hospital and so Scanlon, after giving him some medicine to deaden the pain and receiving his fee of ten shillings, he left, promising to return later. Despite being nursed by Sara Trassjonsky, Gardstein died later that night.

The following day Dr. Scanlon told the police about treating Gardstein for gun-shot wounds. Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley and Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson arrived to find Trassjonsky burning documents. Soon afterwards, a Daily Chronicle journalist arrived: "The room itself is about ten feet by nine, and about seven feet high. A gaudy paper decorates the walls and two or three cheap theatrical prints are pinned up. A narrow iron bedstead painted green, with a peculiarly shaped head and foot faces the door. On the bedstead was a torn and dirty woollen mattress, a quantity of blood-stained clothing, a blood-stained pillow and several towels also saturated with blood. Under the window stood a string sewing machine, and a rickety table, covered with a piece of mole cloth, occupied the centre of the room. On it stood a cup and plate, a broken glass, a knife and fork, and a couple of bottles and a medicine bottle. Strangely contrasting with the dirt and squalor, a painted wooden sword lay on the table, and another, to which was attached a belt of silver paper, lay on a broken desk supported on a stool. On the mantelpiece and on a cheap whatnot stood tawdry ornaments. In an open cupboard beside the fireplace were a few more pieces of crockery, a tin or two, and a small piece of bread. A mean and torn blind and a strip of curtain protected the window, and a roll of surgeon's lint on the desk. The floor was bare and dirty, and, like the fireplace, littered with burnt matches and cigarette ends - altogether a dismal and wretched place to which the wounded desperado had been carried to die." Another journalist described the dead man "as handsome as Adonis - a very beautiful corpse."

The Hunt for Fritz Svaars and Peter the Painter

The police found a Dreyse gun and a large amount of ammunition for a Mauser gun in the room. In Gardstein's pocket book was a member's card dated 2nd July, 1910, certifying that he was a member of Leesma, the Lettish Communist Group. There was also a letter from Fritz Svaars: "All around I see awful things which I cannot tell you. I do not blame our friends as they are doing all that is possible, but things are not getting better. The life of the workman is full of pain and suffering, but if the suffering reaches a certain degree one wonders whether it would not be better to follow the example of Rainis (an author of Lettish poems) who says burn at once so that you may not suffer long, but one feels that one cannot do it although it seems very advisable. The outlook is always the same, awful outlook for which we must sacrifice our strength. There is not and cannot be another outlet. Under such circumstances, our better feelings are at war with those who live upon our labour. The weakest part of our organisation is that we cannot do sufficient for our friends who are falling."

Despite the fact that these men were Lettish communists linked to the Bolsheviks, the media continued to argue that they were Russian Anarchists: The Daily Telegraph reported: "Anarchist literature, in sufficient quantities to corroborate the suspicion of the police that they are face to face with a far-reaching conspiracy, rather than an isolated and unpremeditated attack on civil authority, is stated to have been recovered. It is reported, in addition, that a dagger was found and a belt, which is understood to have had placed within it 150 Mauser dumdum bullets - bullets, that is, with soft heads, which, upon striking a human body, would spread and inflict a wound of a grievous, if not fatal character."

The police offered a £500 reward for the capture of the men responsible for the deaths of Charles Tucker, Robert Bentley and Walter Choat. One man who came forward was Nicholas Tomacoff, who had been a regular visitor to 59 Grove Street. He told them that he knew that identities of three members of the gang. This included Yakov Peters. On 22nd December, 1910, Tomacoff took the police to 48 Turner Street, where Peters was living. When he was arrested Peters answered: "It is nothing to do with me. I can't help what my cousin Fritz (Svaars) has done."

Tomacoff also provided information on Yourka Dubof. He was described as "twenty-one, 5 feet 8 inches in height of pale complexion, with dark-brown hair". When he was arrested he commented: "You make mistake. I will go with you." He admitted that he had been at 59 Grove Street on the afternoon of 16th December 1910. He said he had gone to see Peter, who he knew was a painter, in an attempt to find work, as he had just been sacked from his previous job. At the police station Dubof and Peters were identified by Isaac Levy, as two of the men carrying George Gardstein in Cutler Street.

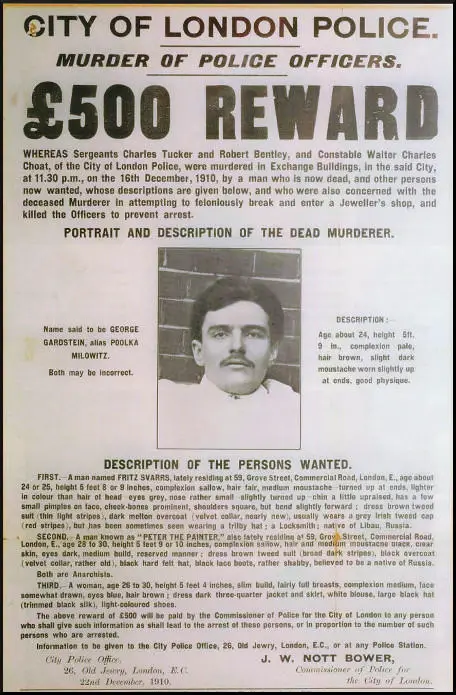

The City of London Police now issued a wanted poster with descriptions of two of the men, Fritz Svaars and Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), that Tomacoff had told them about: "Fritz Svarrs, lately residing at 59 Grove Street... age about 24 or 25, height 5 feet 8 or 9 inches, complexion sallow, hair fair, medium moustache - turned up at ends, lighter in colour than hair of head - eyes grey, nose rather small - slightly turned up - chin a little upraised, has a few small pimples on face, cheek-bones prominent, shoulders square but bend slightly forward: dress brown tweed suit (thin light stripes), dark melton overcoat (velvet collar, nearly new), usually wears a grey Irish tweed cap (red stripes), but has been sometimes seen wearing a trilby hat."

The police did not have the name of the second wanted man: "A man known as Peter the Painter, also lately residing at 59 Grove Street... age 28 to 30, height 5 feet 9 or 10 inches, complexion sallow, hair and medium moustache black, clear skin, eyes dark, medium build, reserved manner; dress brown tweed suit (broad dark stripes), black overcoat (velvet collar, rather old), black hard felt hat, black lace boots, rather shabby, believed to be a native of Russia. Both are Anarchists."

The poster also included a photograph of a dead George Gardstein, who was described as "age about 24, height 5 feet 9 inches, complexion pale, hair brown, slight dark moustache worn slightly up at ends, good physique." The poster also contained the information: "The above reward of £500 will be paid by the Commissioner of Police for the City of London to any person who shall give such information as shall lead to the arrest of these persons, or in proportion to the number of such persons who are arrested."

The Siege of Sidney Street

On 1st January, 1911, the police was told that they would find the men in the lodgings rented by a Betsy Gershon at 100 Sidney Street. It seems that one of the gang, William Sokolow, was Betsy's boyfriend. This was part of a block of 10 houses just off Commercial Road. The tenant was a ladies tailor, Samuel Fleischmann. With his wife and children he occupied part of the house and sublet the rest. Other residents included an elderly couple and another tailor and his large family. Betsy had a room at the front of the second floor.

Superintendent Mulvaney was put in charge of the operation. At midday on 2nd January, two large horse-drawn vehicles concealing armed policeman were driven into the street and the house placed under observation. By the afternoon over 200 officers were on the scene, with armed men stationed in shop doorways facing the house. Meanwhile, plain-clothed policemen began to evacuate the residents of 100 Sidney Street.

Mulvaney decided that any attempt to arrest the men would be very difficult. He later recalled: "The measurements of the passage and staircase will show how futile any attempt to storm or rush the place would have been, with two men... dominating the position from the head of the stairs and where, to an extent, they were well under cover from fire. The passage at one discharge would have been blocked by fallen men; had any even reached the stairs, it could only have been by climbing over the bodies of their comrades, when they would stand little chance of getting further; had they even done this the two desperadoes could retreat up the staircase to the first and second storey, on each of which, what had occurred below would have been repeated."

At daybreak Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley gave orders for a brick to be thrown at the window of Betsy Gershon's room. The men inside responded by firing their guns. Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson was hit and collapsed to the ground. Wensley went to help him. Leeson is recorded as saying: "Mr Wensley, I am dying. They have shot me through the heart. Goodbye. Give my love to the children. Bury me at Putney." Dr. Nelson Johnstone examined him and discovered the wound was level with the left nipple and about two inches in towards the centre of the chest.

Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, decided to go to Sidney Street. His biographer, Clive Ponting, commented: "His presence had been unnecessary and uncalled for - the senior Army and police officers present could easily have coped with the situation on their own authority. But Churchill with his thirst for action and drama could not resist the temptation." As soon as he arrived Churchill ordered the troops to be called in. This included 21 Scots Guards marksmen who took up their places on the top floor of a nearby building.

Philip Gibbs, was reporting the Siege of Sidney Street for the The Daily Chronicle and had positioned himself on the roof of The Rising Sun public house: "In the top-floor room of the anarchists' house we observed a gas jet burning, and presently some of us noticed the white ash of burnt paper fluttering out of a chimney pot... They were setting fire to the house, upstairs and downstairs. The window curtains were first to catch alight, then volumes of black smoke, through which little tongues of flame licked up, poured through the empty window frames. They must have used paraffin to help the progress of the fire, for the whole house was burning with amazing rapidity."

Assistant Divisional Officer of the London Fire Brigade, Cyril Morris, was told to report to Winston Churchill: "As I arrived at the fire. I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen - thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must he there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house. from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols. I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations." Morris was shocked when Churchill told him to "Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders."

Philip Gibbs described how the men inside the house fired on the police: "For a moment I thought I saw one of the murderers standing on the window sill. But it was a blackened curtain which suddenly blew outside the window frame and dangled on the sill. A moment later I had one quick glimpse of a man's arm with a pistol in his hand. He fired and there was a quick flash. At the same moment a volley of shots rang out from the Guardsmen opposite. It is certain that they killed the man who had shown himself, for afterwards they found his body (or a bit of it) with a bullet through the skull. It was not long afterwards that the roof fell in with an upward rush of flame and sparks. The inside of the house from top to bottom was a furnace. The detectives, with revolvers ready, now advanced in Indian file. One of them ran forward and kicked at the front door. It fell in, and a sheet of flame leaped out. No other shot was fired from within."

Death of Fritz Svaars

Cyril Morris was one of those who searched the building afterwards: "We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas."

The police identified the two dead men as Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. It was believed that Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter) had escaped from the burning building. The bodies were taken to Ilford Cemetery and carried into the church. When the chaplain was told of their identity he expressed his strong disapproval of their bodies being brought into the church and said that it was an outrage to public decency that they should be buried in the same ground as two of the murdered policemen. Later that day they were buried in unconsecrated ground without a religious service.

Primary Sources

(1) Fritz Svaars, letter to George Gardstein (undated)

All around I see awful things which I cannot tell you. I do not blame our friends as they are doing all that is possible, but things are not getting better.

The life of the workman is full of pain and suffering, but if the suffering reaches a certain degree one wonders whether it would not be better to follow the example of Rainis (an author of Lettish poems) who says burn at once so that you may not suffer long, but one feels that one cannot do it although it seems very advisable. The outlook is always the same, awful outlook for which we must sacrifice our strength. There is not and cannot be another outlet. Under such circumstances, our better feelings are at war with those who live upon our labour. The weakest part of our organisation is that we cannot do sufficient for our friends who are falling. For instance, such an incident occurred last week. I had to send 10 roubles to Milan Prison for S. German who is to be transferred to another prison. I also had to secure the necessary for Krustmadi, and this evening I received news from Libau prison that one of our friends of last summer has been taken there without any money. We ought to help but we have only 33 kopecks and the treasury of the Red X is quite empty. It is terrible because the prisoner may think we will not help him!

(2) The Daily Telegraph (27th December, 1910)

Anarchist literature, in sufficient quantities to corroborate the suspicion of the police that they are face to face with a far-reaching conspiracy, rather than an isolated and unpremeditated attack on civil authority, is stated to have been recovered.

It is reported, in addition, that a dagger was found and a belt, which is understood to have had placed within it 150 Mauser dumdum bullets - bullets, that is, with soft heads, which, upon striking a human body, would spread and inflict a wound of a grievous, if not fatal character.

(3) Superintendent Mulvaney, statement (4th January, 1911)

The measurements of the passage and staircase will show how futile any attempt to storm or rush the place would have been, with two men... dominating the position from the head of the stairs and where, to an extent, they were well under cover from fire. The passage at one discharge would have been blocked by fallen men; had any even reached the stairs, it could only have been by climbing over the bodies of their comrades, when they would stand little chance of getting further; had they even done this the two desperadoes could retreat up the staircase to the first and second storey, on each of which, what had occurred below would have been repeated.

(4) Cyril Morris, Fire! On the work of the London and other Fire Brigades (1939)

As I arrived at the fire. I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen - thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must he there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house. from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols.

I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations. His order to me was 'Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders.' While being duly thankful for this order. I never can understand why the then Home Secretary took executive charge of a situation requiring the most careful handling as between the police and fire brigade. and as we shall see in a moment, he gave me a wrong order.

Had I been a more experienced officer, I should have taken orders from nobody - advice from the police, yes, Under the conditions, but orders, definitely no. At a Fire in London the Chief Officer of thc LFB or his representative

is granted by Act of Parliament absolutely full plenary powers. There can be no officer who has such a wide authority under normal peacetime conditions, and this authority is very necessary at times when immediate decisions have to he made involving the protection of' perhaps millions pounds worth of property.After receiving this order I took stock of the position. The front rooms on the first and second floors were starting to emit dense clouds of smoke, which shortly turned to flames. The firing from the house was gradually ceasing. Shortly afterwards the flames reached the roofs, which blazed up, the fire spreading to the adjoining roofs, this being one of a row of terraced houses. By this time we in the Brigade were to say the least getting somewhat restless. How far would the fire spread before we could start to attack it? The LFB Superintendent kept urging me to do something, but the Home Secretary was a very important dignitary to a junior officer, so I sat tight while the fire continued to spread.

The houses all had a projecting back addition containing two rooms. As the front windows had been broken by shots before the fire started. the draft from the fire had carried it to the front and in all probability the back two rooms were intact. No sooner had we realised what we might he up against - a burst of firing from the back of the house as soon as we approached it - than the order came "You can now approach the fire."

So up we dashed with our lines of hose, through adjoining property to the back of the house followed by Mr. Wensley of the Metropolitan Police and we found the rooms absolutely intact, not even filled with smoke. Fortunately by that time the criminals were no longer in a position to fire on us. As we made our way through the back of the house the order was given to turn on the water.

While our party approached the back, another hose line was taken along the side of the street, up an adjoining house and on to the roof to attack the fire from above. By this time the house was well alight. The fire had travelled right down to the ground floor and the roofs of the houses on each sided had caught. In a few minutes the fire would have spread right along Sidney Street along both sides of the house we were attacking...

We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas.

(5) Philip Gibbs, Adventures in Journalism (1923)

For some reason, which I have forgotten, I went very early that morning to the Chronicle office, and was greeted by the news editor with the statement that a hell of a battle was raging in Sidney Street. He advised me to go and look at it.

I took a taxi, and drove to the corner of that street, where I found a dense crowd observing the affair as far as they dared peer round the angle of the walls from adjoining streets. Heedless at the moment of danger, which seemed to ridiculous, I stood boldly opposite Sidney Street and looked down its length of houses. Immediately in front of me four soldiers of one of the Guards' regiments lay on their stomachs, protected from the dirt of the road by newspaper "sandwich" boards, firing their rifles at a house halfway down the street. Another young Guardsman, leaning against a wall, took random shots at intervals while he smoked a Woodbine. As I stood near he winked and said, "What a game."

It was something more than a game. Bullets were flicking off the walls like plugging holes into the dirty yellow brick, and ricocheting fantastically. One of them took a neat chip out of a policeman's helmet, and he turned, and he said, "Well, I'll be blowed!" and laughed in a foolish way...

It was a good vantage point (on the roof of the "The Rising Sun"), as we should have called it later in history. It looked right across to the house in Sidney Street in which Peter the Painter and his friends were defending themselves to the death - a tall, thin house of three storeys, with dirty window blinds. In the house immediately opposite were some more Guardsmen, with pillows and mattresses stuffed into the windows in the nature of sandbags as used in trench warfare. We could not see the soldiers, but we could see the effect of their intermittent fire, which had smashed every pane of glass and kept chipping off bits of brick in the anarchists' abode.

The street had been cleared of all onlookers, but a group of detectives slunk along the walls on the anarchists' side of the street at such an angle that they were safe from the slanting fire of the enemy. They had to keep very close to the wall, because Peter and his pals were dead shots and maintained something like a barrage fire with their automatics. Any detective or policeman who showed himself would have been sniped in a second, and these men were out to kill.

The thing became a bore as I watched it for an hour or more, during which time Mr Winston Churchill, who was then Home Secretary, came to take command of active operations, thereby causing an immense amount of ridicule in next day's papers. With a bowler hat pushed firmly down on his bulging brow, and one hand in his breast pocket, like Napoleon on the field of battle, he peered round the corner of the street, and afterwards, as we learned, ordered up some field guns to blow the house to bits.That never happened for a reason which we on "The Rising Sun" were quick to see.

In the top-floor room of the anarchists' house we observed a gas jet burning, and presently some of us noticed the white ash of burnt paper fluttering out of a chimney pot.

"They're burning documents," said one of my friends.

They were burning more than that. They were setting fire to the house, upstairs and downstairs. The window curtains were first to catch alight, then volumes of black smoke, through which little tongues of flame licked up, poured through the empty window frames. They must have used paraffin to help the progress of the fire, for the whole house was burning with amazing rapidity.

"Did you ever see such a game in London!" exclaimed the man next to me on the roof of the public house.

For a moment I thought I saw one of the murderers standing on the window sill. But it was a blackened curtain which suddenly blew outside the window frame and dangled on the sill.

A moment later I had one quick glimpse of a man's arm with a pistol in his hand. He fired and there was a quick flash. At the same moment a volley of shots rang out from the Guardsmen opposite. It is certain that they killed the man who had shown himself, for afterwards they found his body (or a bit of it) with a bullet through the skull. It was not long afterwards that the roof fell in with an upward rush of flame and sparks. The inside of the house from top to bottom was a furnace.

The detectives, with revolvers ready, now advanced in Indian file. One of them ran forward and kicked at the front door. It fell in, and a sheet of flame leaped out. No other shot was fired from within. Peter the Painter and his fellow bandits were charred cinders in the bonfire they had made.

(6) The Daily Chronicle (January, 1911)

At both ends of Sidney Street the Scots Guards were in position, taking cover behind the angle of the houses. Around them were groups of policemen in uniform armed with shot-guns, and numbers of plain clothes detectives with heavy revolvers. In the shadow of doorways and archways men crouched down with barrels of rifles and pistols pointed towards the house next to the doctor's surgery, with its shattered window-panes and broken brickwork. Looking down into the backyards of the houses opposite Martins Buildings, I could see soldiers and armed policemen moving about, climbing over fences, and getting up tall ladders, so that they could fire between the chimney pots.

On the roof of a great brewery on the same side of the way as the Rising Sun public-house were scores of the work people, and as far as the eye could see across the sloping roofs, the chimney-pots and parapets, the sky-line was black with heads, while in the streets below, as far as a quarter of a mile away, there were vast and tumultuous crowds, kept back by lines of mounted policemen. The voices of those many thousands came up to me in great murderous gusts, like the roar of wild beasts in a jungle. It seemed as if the whole of London had poured into Whitechapel and Stepney to watch one of the most deadly and thrilling dramas that has ever happened in the great city within living memory.

But my eyes were now fixed upon one building, and no other impression could find a place in my mind. The anarchists' had the horrible fascination of a house of death. Bullets were raining upon it. As I looked I saw how they spat at the walls, how they ripped splinters from the door, how they made neat grooves as they burrowed into the red bricks, or chipped off corners of them. The noise of battle was tremendous and almost continuous. The heavy barking reports of Army rifles were followed by the sharp and lighter cracks of pistol shots. Some of the weapons had a shrill singing noise, and others were like children's pop guns. Most terrible and deadly in sound was the rapid fire of the Scots Guards, shot speeding on shot, as though a Gatling gun were at work. Then there would come a sudden lull, as though a bugle had sounded "Cease fire", followed by a silence, intense and strange, after the ear-splitting din.

It reopened again when a few moments later there came the spitting fire of an automatic pistol from the house next to the surgery. From my vantage point I could see how the assassins changed the position from which they fired. The idea that only two men were concealed within that arsenal seemed disproved by the extreme rapidity with which their shots came from one floor and another. As I watched, gripped by the horror and drama of it, I saw a sharp stabbing flash break through the garret window. The man's weapon must have been over the edge of the window-sill. He emptied his magazine, spitting out the shots at the house opposite, from which picked marksmen of the Scots Guards replied with instant volleys. A minute later by my watch shots began to pour through the second floor window, and before the echo of them had died away there was a fusillade from the ground floor.So this amazing duel went on, as a distinct clock chimed the quarters and half hours. From 11 o'clock until 12.30 there were not scores or hundreds of shots fired, but thousands. It seemed that the assassins had an almost inexhaustible supply of ammunition.... Blazing timbers were flung into the street, masses of masonry crashed down, fiery splinters, like shooting stars, were hurtled a hundred yards or more. Broken glass fell upon the pavement again and again with a dreadful sound of destruction. And into all this turmoil and fury there poured a terrific artillery of shots. The soldiers were volleying now from every window and every roof on the opposite side of Sidney Street, and their shots had thunderous echoes, for other soldiers and many police were firing into the back of the blazing house from the yard.