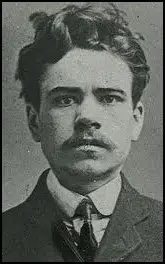

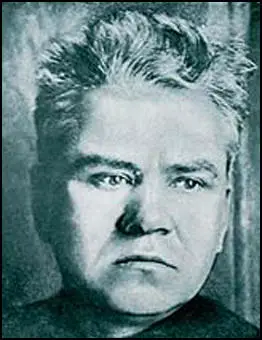

Yakov Peters

Yakov Peters was born into poverty in Aizpute, Latvia on 21st November, 1886. Donald Rumbelow pointed out: "As the son of a Latvian farm-labourer he had experienced all the burdens of degrading forced labour. His schooling had lasted only a few winters; at the age of eight he was tending cattle, and at fourteen he had become a farm-labourer like his father."

As a teenager he joined the Latvian Social Democratic Workers' Party in Riga. Peters founded a party cell in the Libau ship-building yard and openly agitated among the sailors of the Baltic Fleet. Peters took part in the 1905 Russian Revolution. After his arrest he had out his fingernails ripped out. He also saw a fellow prisoner having his genitals removed.

Peters was released but was arrested two years later for the attempted murder of a factory director in Liepāja. He was found not guilty by a military court in 1908. After his release he emigrated to England and lived in London where he joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). He also secured employment as a presser in a second-hand clothing business. Peters associated with other Russians who held revolutionary beliefs, including Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), George Gardstein, Fritz Svaars, Yourka Dubof, Karl Hoffman, Sara Trassjonsky, Nina Vassilleva, John Rosen, Max Smoller and William Sokolow.

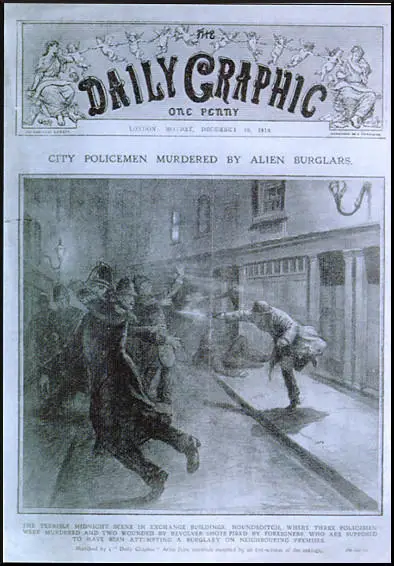

On 16th December 1910, a gang that included Peters, attempted to break into the rear of Henry Harris's jeweller's shop in Houndsditch, from 11 Exchange Buildings in the cul-de-sac behind. The Daily Telegraph reported: "Some two or three weeks ago this particular house in Exchange Buildings was rented and there went to live there two men and a woman. They were little known by neighbours, and kept very quiet, as if, indeed, to escape observation. They are said to have been foreigners in appearance, and the whole neighbourhood of Houndsditch containing a great number of aliens, and removal being not infrequent, the arrival of this new household created no comment. The police, however, evidently had some cause to suspect their intentions. The neighbourhood is always well patrolled. Shortly before 11.30 last night there were sounds either at the back of these newcomers' premises or at Mr Harris's shop that attracted the attention of the police."

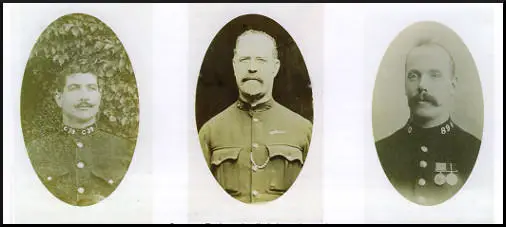

A neighbouring shopkeeper, Max Weil, heard their hammering, informed the City of London Police, and nine unarmed officers arrived at the house. Sergeant Robert Bentley knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings. The door was open by Gardstein and Bentley asked him: "Have you been working or knocking about inside?" Bentley did not answer him and withdrew inside the room. Bentley gently pushed open the door, and was followed by Sergeant Bryant. Constable Arthur Strongman was waiting outside. "The door was opened by some person whom I did not see. Police Sergeant Bentley appeared to have a conversation with the person, and the door was then partly closed, shortly afterwards Bentley pushed the door open and entered." According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "Bentley stepped further into the room. As he did so the back door was flung open and a man, mistakenly identified as Gardstein, walked rapidly into the room. He was holding a pistol which he fired as he advanced with the barrel pointing towards the unarmed Bentley. As he opened fire so did the man on the stairs. The shot fired from the stairs went through the rim of Bentley's helmet, across his face and out through the shutter behind him... His first shot hit Bentley in the shoulder and the second went through his neck almost severing his spinal cord. Bentley staggered back against the half-open door and collapsed backwards over the doorstep so that he was lying half in and half out of the house." Sergeant Bryant later recalled: "Immediately I saw a man coming from the back door of the room between Bentley and the table. On 6 January I went to the City of London Mortuary and there saw a dead body and I recognised the man. I noticed he had a pistol in his hand, and at once commenced to fire towards Bentley's right shoulder. He was just in the room. The shots were fired very rapidly. I distinctly heard 3 or 4. I at once put up my hands and I felt my left hand fall and I fell out on to the footway. Immediately the man commenced to fire Bentley staggered back against the door post of the opening into the room. The appearance of the pistol struck me as being a long one. I think I should know a similar one again if I saw it. Only one barrel, and it seemed to me to be a black one. I next remember getting up and staggered along by the wall for a few yards until I recovered myself. I was going away from Cutler Street. I must have been dazed as I have a very faint recollection of what happened then." Constable Ernest Woodhams ran to help Bentley and Bryant. He was immediately shot by one of the gunman. The Mauser bullet shattered his thigh bone and he fell unconscious to the ground. Two men with guns came from inside the house. Strongman later recalled: "A man aged about 30, height 5 ft 6 or 7, pale thin face, dark curly hair and dark moustache, dress dark jacket suit, no hat, who pointed the revolver in the direction of Sergeant Tucker and myself, firing rapidly. Strongman was shot in the arm, but Sergeant Charles Tucker was shot twice, once in the hip and once in the heart. He died almost instantly. As George Gardstein left the house he was tackled by Constable Walter Choat who grabbed him by the wrist and fought him for possession of his gun. Gardstein pulled the trigger repeatedly and the bullets entered his left leg. Choat, who was a big, muscular man, 6 feet 4 inches tall, managed to hold onto Gardstein. Other members of the gang rushed to his Gardstein's assistance and turned their guns on Choat and he was shot five more times. One of these bullets hit Gardstein in the back. The men pulled Choat from Gardstein and carried him from the scene of the crime. Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof, Peter Piaktow and Fritz Svaars, half dragged and half carried Gardstein along Cutler Street. Isaac Levy, a tobacconist, nearly collided with them. Peters and Dubof lifted their guns and pointed them at Levy's face and so he let them pass. For the next half-hour they were able to drag the badly wounded man through the East End back streets to 59 Grove Street. Max Smoller and Nina Vassilleva, went to a doctor who they thought might help. He refused and threatened to tell the police. They eventually persuaded Dr. John Scanlon, to treat Gardstein. He discovered that Gardstein had a bullet lodged in the front of the chest. Scanlon asked Gardstein what had happened. He claimed that he had been shot by accident by a friend. However, he refused to be taken to hospital and so Scanlon, after giving him some medicine to deaden the pain and receiving his fee of ten shillings, he left, promising to return later. Despite being nursed by Sara Trassjonsky, Gardstein died later that night. The following day Dr. Scanlon told the police about treating Gardstein for gun-shot wounds. Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley and Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson arrived to find Trassjonsky burning documents. Soon afterwards, a Daily Chronicle journalist arrived: "The room itself is about ten feet by nine, and about seven feet high. A gaudy paper decorates the walls and two or three cheap theatrical prints are pinned up. A narrow iron bedstead painted green, with a peculiarly shaped head and foot faces the door. On the bedstead was a torn and dirty woollen mattress, a quantity of blood-stained clothing, a blood-stained pillow and several towels also saturated with blood. Under the window stood a string sewing machine, and a rickety table, covered with a piece of mole cloth, occupied the centre of the room. On it stood a cup and plate, a broken glass, a knife and fork, and a couple of bottles and a medicine bottle. Strangely contrasting with the dirt and squalor, a painted wooden sword lay on the table, and another, to which was attached a belt of silver paper, lay on a broken desk supported on a stool. On the mantelpiece and on a cheap whatnot stood tawdry ornaments. In an open cupboard beside the fireplace were a few more pieces of crockery, a tin or two, and a small piece of bread. A mean and torn blind and a strip of curtain protected the window, and a roll of surgeon's lint on the desk. The floor was bare and dirty, and, like the fireplace, littered with burnt matches and cigarette ends - altogether a dismal and wretched place to which the wounded desperado had been carried to die." Another journalist described the dead man "as handsome as Adonis - a very beautiful corpse." The police found a Dreyse gun and a large amount of ammunition for a Mauser gun in the room. In Gardstein's pocket book was a member's card dated 2nd July, 1910, certifying that he was a member of Leesma, the Lettish Communist Group. Despite the fact that these men were Lettish communists linked to the Bolsheviks, the media continued to argue that they were Russian Anarchists. The Daily Telegraph reported: "Anarchist literature, in sufficient quantities to corroborate the suspicion of the police that they are face to face with a far-reaching conspiracy, rather than an isolated and unpremeditated attack on civil authority, is stated to have been recovered. It is reported, in addition, that a dagger was found and a belt, which is understood to have had placed within it 150 Mauser dumdum bullets - bullets, that is, with soft heads, which, upon striking a human body, would spread and inflict a wound of a grievous, if not fatal character." The police offered a £500 reward for the capture of the men responsible for the deaths of Charles Tucker, Robert Bentley and Walter Choat. One man who came forward was Nicholas Tomacoff, who had been a regular visitor to 59 Grove Street. He told them that he knew that identities of three members of the gang. This included Yakov Peters. On 22nd December, 1910, Tomacoff took the police to 48 Turner Street, where Peters was living. When he was arrested Peters answered: "It is nothing to do with me. I can't help what my cousin Fritz (Svaars) has done." Tomacoff also provided information on Yourka Dubof. He was described as "twenty-one, 5 feet 8 inches in height of pale complexion, with dark-brown hair". When he was arrested he commented: "You make mistake. I will go with you." He admitted that he had been at 59 Grove Street on the afternoon of 16th December 1910. He said he had gone to see Peter, who he knew was a painter, in an attempt to find work, as he had just been sacked from his previous job. At the police station Dubof and Peters were identified by Isaac Levy, as two of the men carrying George Gardstein in Cutler Street. On 1st January, 1911, the police was told that they would find the men in the lodgings rented by a Betsy Gershon at 100 Sidney Street. It seems that one of the gang, William Sokolow, was Betsy's boyfriend. This was part of a block of 10 houses just off Commercial Road. The tenant was a ladies tailor, Samuel Fleischmann. With his wife and children he occupied part of the house and sublet the rest. Other residents included an elderly couple and another tailor and his large family. Betsy had a room at the front of the second floor. Superintendent Mulvaney was put in charge of the operation. At midday on 2nd January, two large horse-drawn vehicles concealing armed policeman were driven into the street and the house placed under observation. By the afternoon over 200 officers were on the scene, with armed men stationed in shop doorways facing the house. Meanwhile, plain-clothed policemen began to evacuate the residents of 100 Sidney Street. Mulvaney decided that any attempt to arrest the men would be very difficult. He later recalled: "The measurements of the passage and staircase will show how futile any attempt to storm or rush the place would have been, with two men... dominating the position from the head of the stairs and where, to an extent, they were well under cover from fire. The passage at one discharge would have been blocked by fallen men; had any even reached the stairs, it could only have been by climbing over the bodies of their comrades, when they would stand little chance of getting further; had they even done this the two desperadoes could retreat up the staircase to the first and second storey, on each of which, what had occurred below would have been repeated." At daybreak Detective Inspector Frederick Wensley gave orders for a brick to be thrown at the window of Betsy Gershon's room. The men inside responded by firing their guns. Detective Sergeant Benjamin Leeson was hit and collapsed to the ground. Wensley went to help him. Leeson is recorded as saying: "Mr Wensley, I am dying. They have shot me through the heart. Goodbye. Give my love to the children. Bury me at Putney." Dr. Nelson Johnstone examined him and discovered the wound was level with the left nipple and about two inches in towards the centre of the chest. Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, decided to go to Sidney Street. His biographer, Clive Ponting, commented: "His presence had been unnecessary and uncalled for - the senior Army and police officers present could easily have coped with the situation on their own authority. But Churchill with his thirst for action and drama could not resist the temptation." As soon as he arrived Churchill ordered the troops to be called in. This included 21 Scots Guards marksmen who took up their places on the top floor of a nearby building. Philip Gibbs, was reporting the Siege of Sidney Street for the The Daily Chronicle and had positioned himself on the roof of The Rising Sun public house: "In the top-floor room of the anarchists' house we observed a gas jet burning, and presently some of us noticed the white ash of burnt paper fluttering out of a chimney pot... They were setting fire to the house, upstairs and downstairs. The window curtains were first to catch alight, then volumes of black smoke, through which little tongues of flame licked up, poured through the empty window frames. They must have used paraffin to help the progress of the fire, for the whole house was burning with amazing rapidity." Assistant Divisional Officer of the London Fire Brigade, Cyril Morris, was told to report to Winston Churchill: "As I arrived at the fire. I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen - thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must he there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house. from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols. I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations." Morris was shocked when Churchill told him to "Stand by and don't approach the fire until you receive further orders." Philip Gibbs described how the men inside the house fired on the police: "For a moment I thought I saw one of the murderers standing on the window sill. But it was a blackened curtain which suddenly blew outside the window frame and dangled on the sill. A moment later I had one quick glimpse of a man's arm with a pistol in his hand. He fired and there was a quick flash. At the same moment a volley of shots rang out from the Guardsmen opposite. It is certain that they killed the man who had shown himself, for afterwards they found his body (or a bit of it) with a bullet through the skull. It was not long afterwards that the roof fell in with an upward rush of flame and sparks. The inside of the house from top to bottom was a furnace. The detectives, with revolvers ready, now advanced in Indian file. One of them ran forward and kicked at the front door. It fell in, and a sheet of flame leaped out. No other shot was fired from within." Cyril Morris was one of those who searched the building afterwards: "We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas." The police identified the two dead men as Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. It was believed that Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter) had escaped from the burning building. The bodies were taken to Ilford Cemetery and carried into the church. When the chaplain was told of their identity he expressed his strong disapproval of their bodies being brought into the church and said that it was an outrage to public decency that they should be buried in the same ground as two of the murdered policemen. Later that day they were buried in unconsecrated ground without a religious service. On 23rd January, 1911, William Bodkin, opened the case for the Crown against Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof and Nina Vassilleva. He made a major mistake in arguing that it was George Gardstein who had shot Robert Bentley and Charles Tucker: "Gardstein was the man who came in flinging open that back door and shot Bentley at his right front; there were also other shots from the man on the stairs.... Several shots were fired at Bentley by the man Gardstein from the back, he advanced to the front door of the house, of that there is no doubt, for we have the hand, according to the evidence of Strongman, protruding through the door of No. 11, so as to sweep the place, firing at Woodhams, Bryant and Martin." Bodkin based his analysis on the discover of the Dreyse gun in Gardstein's room: "Now Gardstein - under his pillow at 59 Grove Street was found exhibit No. 2, which was a Dreyse pistol. A pistol with a magazine, which on examination had been recently fired. It is difficult to say - for any expert to say - when it had been recently fired. It was a pistol rifled in four grooves, and Mr Goodwin, a gentleman who has kindly examined this pistol... has fired some shots from that pistol into sawdust. The cartridges which can be fired from that pistol are quite common cartridges which are standardised and are used for various automatic pistols, but the peculiarity of this Dreyse pistol is that it has four grooves. It appears that six bullets - two from Tucker's body, two from Bentley's body and two from Choat's body - were fired from the Dreyse pistol as they all have four groove marks upon them.... It is clear that Gardstein was the man who fired, and under his pillow a Dreyse pistol was found, and it seems quite proper to assume that he it was who used the Dreyse pistol. The only one to hit Bentley was Gardstein, and Bentley's bullets were from a Dreyse pistol." What the prosecuting counsel had difficulty explaining was the lack of Dreyse ammunition in Gardstein's house. As Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973) has pointed out: "Now it has been wrongly assumed from Mr Bodkin's statement that the pistol was under the pillow for Gardstein to defend himself and to resist arrest. In support of this theory it has been alleged that a cap containing a quantity of ammunition was placed by the bed within easy reach of his hand. Certainly there was a cap with ammunition by the bed but none of it could be fired from the Dreyse... If, in fact, Gardstein had owned the Dreyse, it is reasonable to suppose that some ammunition for this weapon would have been found in his lodgings, which were described as an arsenal as well as a bomb factory. None was found." Rumbelow goes on to argue that the only ammunition "consisted of ... 308 .30 Mauser cartridges, some of D.W.M. (German) manufacture, and the other with plain heads; also 26 Hirtenberger 7.9 mm Mauser rifle cartridges". Rumbelow adds that "it is inconceivable, surely, that a man would have over 300 rounds of ammunition for a Mauser pistol which he didn't possess, and none for the Dreyse he is supposed to have used!" Rumbelow suggested that Yakov Peters had planted his Dreyse gun in the room when along with Yourka Dubof, Peter Piaktow and Fritz Svaars, he had taken Gardstein to 59 Grove Street. Peters realised that Gardstein was dying and that the police would eventually find his body. If they also found the gun that had done most of the killing, they would assume that Gardstein was the man responsible for the deaths of the three policemen. The case was adjourned when another gang members were arrested in February, 1911. The trial of the Houndsditch murders opened at the Old Bailey on 1st May. Yakov Peters and Yourka Dubof were charged with murder. Peters, Dubof, Karl Hoffman, Max Smoller and John Rosen were charged with attempting to rob Henry Harris's jeweller's shop. Sara Trassjonsky and Nina Vassilleva, were charged with harbouring a felon guilty of murder. The opening speech of A. H. Bodkin lasted two and a quarter hours. Justice William Grantham was unimpressed with the evidence presented and directed the jury to say that the two men, against whom there was no evidence of shooting, were not guilty of murder. Grantham added that he believed that the policeman were killed by George Gardstein, Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. "There were three men firing shots and I think they are dead." The prosecution's principal witness that linked Peters and Dubof to Gardstein was Isaac Levy, who saw the men drag him along Cutler Street. Levy came under a fierce attack from defence counsel. After his testimony, Justice Grantham said that if there was no other evidence of identification he could not allow any jury to find a verdict of guilty on Levy's uncorroborated statement. After Grantham's summing-up made it clear that none of the men should be convicted of breaking and entering, the jury found them all not guilty and they were set free. In 1913 he married May Freeman, the daughter of a banker. The following year she had a daughter, Maisie Peters-Freeman. After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. One of the first announcements made by Lvov was that all political exiles were allowed to return to their homes. Peters returned in May and joined the Bolsheviks. On the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace and arrested the Cabinet ministers. On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. In December, 1917, Lenin appointed Felix Dzerzhinsky as Commissar for Internal Affairs and head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka). Soon afterwards Dzerzhinsky appointed Peters as his deputy. Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972), has pointed out: "The truth is that Peters, despite his humble origins and his unostentatious employment in England, was a highly professional revolutionary, a good organiser and an exceptionally intelligent, self-educated man. Dzerzhinsky believed in him because he saw in Peters something of the implacable fanaticism he possessed himself. Soon Peters was to become almost as notorious as Dzerzhinsky." Dzerzhinsky explained in July 1918: "We stand for organized terror - this should be frankly admitted. Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and of the new order of life. We judge quickly. In most cases only a day passes between the apprehension of the criminal and his sentence. When confronted with evidence criminals in almost every case confess; and what argument can have greater weight than a criminal's own confession." On one occasion Peters and Dzerzhinsky took diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart and journalist, Arthur Ransome, on a raid of 26 Anarchist strongholds in Moscow. Lockhart later recorded: " The Anarchists had appropriated the finest houses in Moscow... The filth was indescribable. Broken bottles littered the floors; the magnificent ceilings were perforated with bullet holes. Wine stains and human excrement blotched the Aubusson carpets. Priceless pictures had been slashed to strips. The dead still lay where they had fallen. They included officers in guard's uniforms, students - young boys of twenty - and men who belonged obviously to the criminal class and whom the revolution had released from prison. In the luxurious drawing room of the House Gracheva the Anarchists had been surprised in the middle of an orgy. The long table which had supported the feast had been overturned, and broken plates, glasses, champagne bottles, made unsavoury islands in a pool of blood and spilt wine. On the floor lay a young woman, face downwards. Yakov Peters turned her over. Her hair was dishevelled. She had been shot through the neck and the blood had congealed in a sinister purple clump. She could not have been more than twenty." According to Lockhart, Peters shrugged his shoulders. "Prostitutka," he said, "Perhaps it is for the best." On 17th August, 1918, Moisei Uritsky, the Commissar for Internal Affairs in the Northern Region, was assassinated by Leonid Kannegisser, a young military cadet. Anatoly Lunacharsky commented: "They killed him. They struck us a truly well-aimed blow. They picked out one of the most gifted and powerful of their enemies, one of the most gifted and powerful champions of the working class." The Soviet press published allegations that Uritsky had been killed because he was unravelling "the threads of an English conspiracy in Petrograd". Despite these claims, Robert Bruce Lockhart, Head of Special Mission to the Soviet Government with the rank of acting British Consul-General in Moscow, continued with his plans to overthrow the Bolshevik government. He had a meeting with a senior intelligence agent based in the French Embassy. He was convinced that Colonel Eduard Berzin was genuine in his desire to overthrow the Bolsheviks and was willing to put up some of the money needed: "The Letts are Bolshevik servants because they have no other resort. They are foreign hirelings. Foreign hirelings serve for money. They are at the disposal of the highest bidder." George Alexander Hill, Sidney Reilly and Ernest Boyce were brought into the conspiracy. Over the next week Hill, Reilly and Boyce were having regular meetings with Berzin, where they planned the overthrow of the Bolsheviks. During this period they handed over 1,200,000 rubles. Some of this money came from the American and French governments. Unknown to MI6 this money was immediately handed over to Felix Dzerzhinsky. So also were the details of the British conspiracy. Berzin told the agents that his troops had been to assigned to guard the theatre where the Soviet Central Executive Committee was to met. A plan was devised to arrest Lenin and Leon Trotsky at the meeting was to take place on 28th August, 1918. Robin Bruce Lockhart, the author of Reilly: Ace of Spies (1992) has argued: "Reilly's grand plan was to arrest all the Red leaders in one swoop on August 28th when a meeting of the Soviet Central Executive Committee was due to be held. Rather than execute them, Reilly intended to de-bag the Bolshevik hierarchy and with Lenin and Trotsky in front, to march them through the streets of Moscow bereft of trousers and underpants, shirt-tails flying in the breeze. They would then be imprisoned. Reilly maintained that it was better to destroy their power by ridicule than to make martyrs of the Bolshevik leaders by shooting them." Reilly later recalled: "At a given signal, the soldiers were to close the doors and cover all the people in the Theatre with their rifles, while a selected detachment was to secure the persons of Lenin and Trotsky... In case there was any hitch in the proceedings, in case the Soviets showed fight or the Letts proved nervous... the other conspirators and myself would carry grenades in our place of concealment behind the curtains." However, at the last moment, the Soviet Central Executive Committee meeting was postponed until 6th September. On 31st August 1918, Dora Kaplan attempted to assassinate Lenin. It was claimed that this was part of the British conspiracy to overthrow the Bolshevik government and orders were issued by Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, to round up the agents based in British Embassy in Petrograd. The naval attaché, Francis Cromie was killed resisting arrest. According to Robin Bruce Lockhart: "The gallant Cromie had resisted to the last; with a Browning in each hand he had killed a commissar and wounded several Cheka thugs, before falling himself riddled with Red bullets. Kicked and trampled on, his body was thrown out of the second floor window." Robert Bruce Lockhart was woken by a rough voice ordering him out of bed in Moscow. "As I opened my eyes, I looked up into the steely barrel of a revolver. Some ten men were in my room." As he dressed "the main body of the invaders began to ransack the flat for compromising documents." Lockhart was taken to Lubyanka Prison. He later recalled: "My prison here consists of a small hall, a sitting-room, a diminutive bedroom, a bathroom and a small dressing-room, which I use for my food. The rooms open on both sides on to corridors so that there is no fresh air. I have one sentry one side and two on the other. They are changed every four hours and as each changes, has to come in to see if I am there. This results in my being woken up at twelve and four in the middle of the night." Lockhart was eventually interrogated by Yakov Peters, Dzerzhinsky's deputy at Cheka. "At the table, with a revolver lying beside the writing pad, was a man, dressed in black trousers and a white Russian shirt... His lips were tightly compressed and, as I entered the room, his eyes fixed me with a steely stare." Lockhart added that his face was sallow and sickly, as he never saw the light of day. Lockhart, who was an accredited diplomat, complained about his treatment. Peters ignored these comments and asked him if he knew Dora Kaplan. When he explained that he had never heard of her, Peters asked him about the whereabouts of Sidney Reilly. Lockhart now knew that Cheka had discovered the British plot against Lenin. This was confirmed when he produced the letter Lockhart had personally written for Colonel Eduard Berzin as an introduction to General Frederick Cuthbert Poole, the head of the British invasion force in Northern Russia. Despite the evidence he had against him, Peters decided to release Lockhart. On 2nd September, 1918, Bolshevik newspapers splashed on their front pages the discovery of an Anglo-French conspiracy that involved undercover agents and diplomats. One newspaper insisted that "Anglo-French capitalists, through hired assassins, organised terrorist attempts on representatives of the Soviet." These conspirators were accused of being involved in the murder of Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Lenin. Lockhart and Reilly were both named in these reports. "Lockhart entered into personal contact with the commander of a large Lettish unit... should the plot succeed, Lockhart promised in the name of the Allies immediate restoration of a free Latvia." An edition of Pravda declared that Lockhart was the main organiser of the plot and was labelled as "a murderer and conspirator against the Russian Soviet government". The newspaper then went on to argue: "Lockhart... was a diplomatic representative organising murder and rebellion on the territory of the country where he is representative. This bandit in dinner jacket and gloves tries to hide like a cat at large, under the shelter of international law and ethics. No, Mr Lockhart, this will not save you. The workmen and the poorer peasants of Russia are not idiots enough to defend murderers, robbers and highwaymen." The following day Robert Bruce Lockhart was arrested and charged with assassination, attempted murder and planning a coup d'état. All three crimes carried the death sentence. The couriers used by British agents were also arrested. Lockhart's mistress, Maria Zakrveskia, who had nothing to do with the conspiracy, was also taken into custody. Xenophon Kalamatiano, who was working for the American Secret Service, was also arrested. Hidden in his cane was a secret cipher, spy reports and a coded list of thirty-two spies. However, Sidney Reilly, George Alexander Hill, and Paul Dukes had all escaped capture and had successfully gone undercover. Yakov Peters interrogated Lockhart for several days. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette (2013) has pointed out: "Lockhart found Peters a curious figure, half bandit and half gentleman. He brought books for Lockhart and made a great show of his generosity. Yet he had a ruthless streak that chilled the blood. He had lived for some years in England as an anarchist exile and had even been tried at the Old Bailey for the murder of three policemen. To the surprise of many, he had been acquitted. In conversations with Lockhart he recalled the happy years he had spent living in London as a gangster. After five days of imprisonment in the Loubianka, Lockhart was transferred to the Kremlin. Accusations continued to be levelled against him in the press and he was told that he was to be put on trial for his life. Yet the trial was continually delayed and he eventually heard that it was unlikely to go ahead." On 2nd October, 1918, the British government arranged for Lockhart to be exchanged for captive Soviet officials such as Maxim Litvinov. Peters was made Chief of Internal Defence and on 14th June 1919 Pravda printed an order by Peters that the wives and grown-up children of all officers escaping to the anti-Bolshevik ranks should be arrested. The following day he ordered the disconnection of all private telephones in Petrograd and the confiscation of all wine, spirits, money above £500 and jewels. In Petrograd he insisted that all citizens had to carry identity cards issued by Cheka. He also had three thousand hostages transported to Moscow. Arthur Ransome was a journalist working in Petrograd who got to know Peters during this period. He described him as being "a small man with a square forehead, very dark eyes and a quick expression... he speaks fair English, though he is gradually forgetting it. He knows far less now than a year ago." Ransome enjoyed the company of Peters and described him as a man of "scrupulous honesty". Peters told Ransome that his methods was keeping crime under control: "We have now shot eight robbers, and we posted the fact at every street corner, and there will be no more robbery. I have now got such a terrible name that if I put up a notice that people will be dealt with severely that is enough, and there is no need to shoot anybody." Arno Walter Dosch-Fleurot, an American journalist working in Russia reported that "the most awful figure of the Russian Red Terror, the man with the most murder on his soul, is the present Extraordinary Commissioner against Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, a dapper little blond Lett named Peters, who lived in England so long that he speaks Russian with an English accent." Dosch-Fleurot attempted to obtain a visa for a Russian woman he knew who wished to visit her parents in England. When Peters learned that her father was an officer he refused point-blank to help. "I protested that the girl was working for her living." Peters replied, "No matter. She belongs to a class we must destroy. We are fighting for our lives." Lenin defended the work of Peters and Cheka by publicly stating: "What surprises me about the howls over the Cheka's mistakes is the inability to take a large view of the question. We have people who seize on particular mistakes by the Cheka, sob and fuss over them... When I consider the Cheka's activity and compare it with these attacks, I say this is narrow-minded, idle talk which is worth nothing... When we are reproached with cruelty, we wonder how people can forget the most elementary Marxism.... The important thing for us to remember is that the Chekas are directly carrying out the dictatorship of the proletariat, and in this respect their role is invaluable." During the Red Terror it is claimed by Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972): "Peters conducted interrogations daily and when he was not engaged in this work he was furiously signing death warrants, often not looking to see what he was signing. During one visit a visitor from a neutral country noticed that Peters signed an order to shoot seventy-two officers without even glancing down at the paper. His amiability had gone and he snapped out his replies to questions." One source heard him say "I am so tired I cannot think. I am worn out signing orders for executions." In his book Deacon goes onto defend Peters: "But to portray Peters solely as a monster is to give a one-sided picture of the man. He was a dispassionate operator, dedicated more to efficiency and speed than to sadism. He was quite unlike some of the animalistic executioners of the Terror: he took no pleasure in his grim work and indeed he often berated his men for prolonging torture and death as a needless waste of time. Those who knew him testified to many small kindnesses which he performed when off duty: he delighted in speaking English on every possible occasion and, in fact, his pro-British and pro-American prejudices caused suspicion among his colleagues." In 1920 Peters was sent to Turkestan where he was placed in charge of suppressing anti-Bolshevik forces. He returned to Moscow in 1922 and became the chief of the Eastern department of the All-Union State Political Administration (OGPU). May Peters-Freeman and her daughter, Maisie, went to live in Russia. However, they discovered that Peters had a new family. In 1937 Joseph Stalin ordered the arrest of a large number of Bolsheviks who were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. This included Yakov Peters, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky. They were all found guilty and were either executed or died in labour camps. Yakov Peters was executed on 25th April, 1938.The Houndsditch Murders

The Death of George Gardstein

The Hunt for Fritz Svaars and Peter the Painter

The Siege of Sidney Street

Houndsditch Murder Trial

Russian Revolution

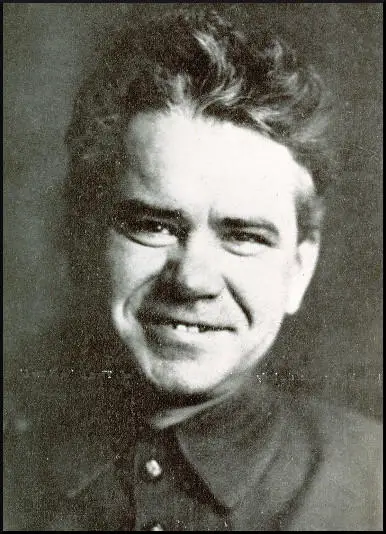

Cheka

Red Terror

Arrest of Robert Bruce Lockhart

Chief of Internal Defence

OGPU

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

The truth is that Peters, despite his humble origins and his unostentatious employment in England, was a highly professional revolutionary, a good organiser and an exceptionally intelligent, self-educated man. Dzerzhinsky believed in him because he saw in Peters something of the implacable fanaticism he possessed himself.

Despite his reputation Peters was a gregarious fellow who was known and liked by the American correspondents in Russia because he seemed more cultivated than the rest. To the Americans he showed quite a different face than he did to the counter-revolutionaries, whom he often ordered to be shot without sending them before Krylenko, the president of the Revolutionary Tribunal...

But to portray Peters solely as a monster is to give a one-sided picture of the man. He was a dispassionate operator, dedicated more to efficiency and speed than to sadism. He was quite unlike some of the animalistic executioners of the Terror: he took no pleasure in his grim work and indeed he often berated his men for prolonging torture and death as a needless waste of time. Those who knew him testified to many small kindnesses which he performed when off duty: he delighted in speaking English on every possible occasion and, in fact, his pro-British and pro-American prejudices caused suspicion among his colleagues. Peters was extremely efficient and was regarded as the prince of interrogators who could conjure information out of almost anyone. It was he who interrogated Bruce Lockhart in the Loubianka Prison, but there he met his match: Lockhart merely claimed diplomatic privilege. Peters was too subtle to challenge his rights.

Nevertheless, even so ardent a Bolshevik as Peters was regarded as something of a security risk among some of the Bolshevik leaders. He owed his strength to the support he received from Dzerzhinsky and few would go against the head of the Cheka. It may have been his Lettish origins which had something to do with this, for many Letts were to be found among the counter-revolutionaries. Or it may have been his pro-British sentiments, or the fact that he had an English wife who was still safe in England. Or even that somebody had heard him make unfavourable comments about the "untidy revolutionary men". Then again his record as a "police butcher" may have made him enemies, as they did that other Cheka killer, Uritsky.

One of Peters' special interests was in organising spies to discover hidden counter-revolutionary loot and to steal art treasures from museums to raise funds for the Soviet at a time when currency was in short supply. Then in October 1920 came a report that Peters, "with his friend, Miss Krause", had left Russia, taking with him a large quantity of valuables which had been entrusted to his care by the Bolshevik Government. He was believed to have gone to Germany and, according to a report in a Petrograd journal, several Bolshevik Commissioners had set out to look for him.

A few years later Peters was reported to have been engaged in counter-espionage work directed against certain officers in the Red Army. Then in 1937 it was reported from Warsaw that he had been executed for plotting against Stalin, along with Valery Meshlauk, head of the State Planning Commission, and Ivan Meshlauk, General Commissioner of the Soviet Pavilion at the recent Paris Exhibition.

The mystery of Jacob Peters lasted until almost the end of World War II. Then Peters' British wife's brother, Mr. D. Freeman, stated that the rumour that his brother-in-law had been executed was not true. "I know Peters is alive and holds a high position in Moscow," he told the London News Chronicle. According to him, Peters' wife and daughter had gone out to Russia to join their husband and father some years before this.

Even some hardened Bolsheviks were perturbed at the extent of the terror under Lenin and articles in Pravda suggested there were "differences of opinion" in the Party as to whether and how far the arrests carried out by the Cheka were necessary. One writer, Olminsky, complained that "under existing Cheka regulations local Chekas could shoot nearly any Party member they chose."

(2) Robert Bruce Lockhart, Memoirs of a British Agent (1934)

The Anarchists had appropriated the finest houses in Moscow... The filth was indescribable. Broken bottles littered the floors; the magnificent ceilings were perforated with bullet holes. Wine stains and human excrement blotched the Aubusson carpets. Priceless pictures had been slashed to strips. The dead still lay where they had fallen. They included officers in guard's uniforms, students - young boys of twenty - and men who belonged obviously to the criminal class and whom the revolution had released from prison. In the luxurious drawing room of the House Gracheva the Anarchists had been surprised in the middle of an orgy. The long table which had supported the feast had been overturned, and broken plates, glasses, champagne bottles, made unsavoury islands in a pool of blood and spilt wine. On the floor lay a young woman, face downwards. Yakov Peters turned her over. Her hair was dishevelled. She had been shot through the neck and the blood had congealed in a sinister purple clump. She could not have been more than twenty. Peters shrugged his shoulders. "Prostitutka," he said, "Perhaps it is for the best."

(3) Donald Rumbelow, The Siege of Sidney Street (1973)

In exile, from 1909 to 1917, Peters had been an active member of the Latvian Social Democratic Party London group. He opposed the Menshevik Central Committee, and in the summer of 1912 succeeded in establishing an L.S.D. Bolshevik Foreign Bureau in London. The revolution of February 1917 opened up the road to Russia for Peters, and the Foreign Bureau sent him back as its representative. In Petrograd he was made a member of the Bolshevik Military Organisation and was sent to Latvia to agitate and propagandise among the Lettish battalions, as he had done in 1905. He seized every opportunity to spread propaganda among the soldiers, and spoke at meetings, conferences, demonstrations and funerals. He became one of the editors of a Bolshevik Latvian newspaper and did not hesitate to unmask, ridicule and morally destroy his enemies.

When support for the Bolsheviks waned and Lenin went into hiding Peters continued to agitate for Bolshevik support. On 23 September 1917 he opened and presented the main report to the 14th Conference of the Latvian Territory Social Democratic Party held in Valka. He spoke of the coming revolution, of the inevitable victory of the working class. He urged that only convinced Bolsheviks should be sent to the Second All Russian Congress of Soviets. "The situation is grave and time is ripe. We must take power in our hands, save Russia and call the peoples to fight a revolutionary battle all over Europe." The Latvian delegates sent him as their delegate to the congress where he was elected a member of the All Russian Central Executive Committee.

He was included in the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, which in fact masterminded the October coup d'etat and Bolshevik seizure of power. Two months after the October revolution the Cheka was formed to combat counter-revolution; Peters was appointed Deputy Chairman to the fanatical Dzerzhinsky.

(4) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Lockhart found Peters a curious figure, half bandit and half gentleman. He brought books for Lockhart and made a great show of his generosity. Yet he had a ruthless streak that chilled the blood. He had lived for some years in England as an anarchist exile and had even been tried at the Old Bailey for the murder of three policemen. To the surprise of many, he had been acquitted. In conversations with Lockhart he recalled the happy years he had spent living in London as a gangster. After five days of imprisonment in the Loubianka, Lockhart was transferred to the Kremlin. Accusations continued to be levelled against him in the press and he was told that he was to be put on trial for his life. Yet the trial was continually delayed and he eventually heard that it was unlikely to go ahead.

(5) Donald Rumbelow, The Siege of Sidney Street (1973)

Jacob Peters, after an initial nervousness, was indifferent, genuinely so, as to what happened to him. His strength was his indifference to death. As the son of a Latvian farm-labourer he had experienced all the burdens of degrading forced labour. His schooling had lasted only a few winters; at the age of eight he was tending cattle, and at fourteen he had become a farm-labourer like his father. In 1904, when he was eighteen, he had left the farm and moved to Riga where he joined the illegal Latvian Social Democrats Labourers Party. During the war with Japan Peters founded a party cell in the Libau ship-building yard and openly agitated among the sailors of the Baltic Fleet. He led a strike in the shipbuilding yard, but in the terror which swiftly followed the 1905 uprising he was flung into prison on a fake attempted-murder charge. Not realising his importance, or the part he had played in the uprising, his captors had limited his torture to beatings-up and ripping out his fingernails. Later Peters recalled how they had tortured a fellow prisoner - who may well have been tortured with him - by not only ripping out his fingernails, but also perforating his eardrums and tearing off his genitals.

Peters was detained for nearly two years. In the autumn of 1907 he and the other prisoners went on hunger strike and demanded to be manacled whenever they were taken out of the prison, as batches of prisoners that had formerly gone out had always been shot for allegedly escaping.

He had been released in 1909 and fled to England before the full extent of his complicity in the uprising was known. Peters joined several left-wing groups to improve his "theoretical and political education", and studied English which he apparently spoke with a Cockney accent acquired in the sweat shop where he worked as a tailor's presser. Unquestionably his share of the expropriation, if it had succeeded, would have gone to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. He had no intention of shouldering responsibility when the police and Press were blaming Fritz and Peter the Painter for the murders, and there was a possibility of his wriggling out. His first words when he was arrested had been, "It is nothing to do with me. I can't help what my cousin Fritz has done." Yet even he must have wondered how he was going to shake the evidence of the eyewitness who had seen him and Dubof with guns in their hands dragging Gardstein out of Exchange Buildings.

Dubof had been arrested on the same day as Peters. By an incredible coincidence he had been recognised in the prison hospital by another prisoner, John Hayes, who was completely unknown to him but who had seen him in Exchange Buildings on the day of the robbery, not once but three times. Hayes had been a policeman for twelve years, before being dismissed and sentenced to a month's hard labour for theft; several minor convictions had followed and he was on release when he saw Dubof. He hadn't been surprised at the close scrutiny Dubof had given him as the years in the force had left their mark and he was used to being mistaken for a detective. When he saw Dubof in the prison hospital he immediately recognised him again and suspected at once that he might be connected with the murders. He slipped him a newspaper with Gardstein's picture on the front page to see how he reacted. Dubof went deadly pale and repeatedly kissed the photograph before folding it up and putting it under his pillow.

Hayes immediately told the prison governor and the police. His story was checked and found to be true. In his statement he described a woman who had been standing with Dubof in Exchange Buildings, but omitted to mention another man who had been standing only a few feet away. On 15/16 February 1911 he saw this man exercising in the prison yard. Hayes only knew him as B1-26, the prison governor as John Rosen alias "the Barber".