Rudolf Schmundt

Rudolf Schmundt was born in Metz on 13th August, 1896. A career officer he served as a lieutenant for the German Army during the First World War. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1938, colonel in 1939, major-general in 1942, and lieutenant general in 1943. (1)

Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg developed a plot to kill Adolf Hitler. To carry out the assassination, it was necessary for Stauffenberg to have access to Hitler. General Friedrich Fromm was Commander in Chief of the Reserve Army. His was in charge of training and personnel replacement for combat divisions of the German Army and had regular meetings with Hitler. (2)

A close friend of Schmundt, suggested that Stauffenberg should become chief of staff to General Fromm. According to Albert Speer, "Schmundt explained to me, Stauffenberg was considered one of the most dynamic and competent officers in the German army. Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg. In spite of his war injuries (he had lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers of his left hand), Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic and at the same time precise, thus showing the marks of the two major and seemingly incompatible educational influences upon him: the circle around the poet Stefan George and the General Staff. He and I would have hit it off even without Schmundt's recommendation." (3)

On 11th July, Stauffenberg flew to Hitler's headquarters in Berchtesgaden. He had a bomb with him but did not set it off because Heinrich Himmler or Hermann Göring were not at the meeting. According to Peter Hoffmann: "There was never any certainty that Himmler or Göring would be present at the briefing conferences; neither of them attended regularly. They were usually represented by their liaison officers who reported to them; they themselves came comparatively seldom. Sometimes Himmler and Göring had no personal contact with Hitler for weeks; at other times one of the other would attend several conferences with Hitler daily." (4) Stauffenberg remained committed to trying to kill Hitler although he had little confidence he would be successful. On 14th July he was quoted as saying: "The worst thing is knowing that we cannot succeed and yet that we have to do it, for our country and our children." (5)

Claus von Stauffenberg had another meeting with Adolf Hitler on 15th July. Although he had the bomb with him he did not take this opportunity to kill Hitler. The main reason was probably the difficulty he would have had in fusing his bomb. Since he only had three fingers on one hand he had to use a pair of pliers and this would certainly have been seen. It has been claimed that if he had bent down "to his briefcase and began to open it with his three fingers - someone would certainly have come to his assistance, lifted it on to the table and helped him take out the papers - impossible then to search round for the pliers, squeeze the fuse and put the briefcase back on the floor." (6)

Stauffenberg needed help in his task and his adjutant, Werner von Haeften, agreed to help assassinate Hitler, when he told his brother, the diplomat, Hans-Bernd von Haeften, also a member of the conspiracy, he raised objections on religious grounds. For sometime he had become entangled in a web of philosophical and religious reflection. He asked Werner: "Are you absolutely sure this is your duty before God and our forefathers?" Werner replied that the act was justified because it would bring an end to the war and would therefore save the lives of many Germans. (7)

Claus von Stauffenberg was now convinced that he was morally justified in taking this action. His religious and ethical beliefs led him to the conclusion that it was his duty to eliminate Hitler and his murderous regime by any means possible. Just before he left on his mission to kill Hitler he said: "It is now time that something was done. But he who has the courage to do something must do so in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor. If he does not do it, however, he will be a traitor to his conscience." (8)

Other members of the conspiracy also urged action. Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, who had been an integral part of the resistance from the beginning, continued to argue that the attempt must be made, regardless of the consequences. As Theodore S. Hamerow pointed out: "Some of those involved in planning the coup started to suggest that the attempt to overthrow the Nazi regime must be made not primarily to save Germany but as an act of atonement or expiation. Even if it should fail, even if the fatherland should be conquered and occupied, the resistance must wage its struggle against National Socialism as a moral obligation, as a sacrifice for mankind, as an appeal for forgiveness and redemption... What mattered was proving to the world that at least some Germans, acting out of conscience and in accordance with universal moral values, were willing to sacrifice themselves to protect humanity against an unspeakable evil." (9)

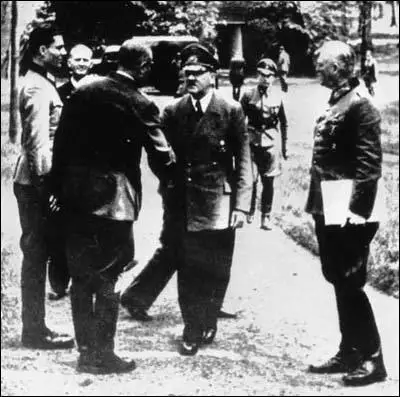

to attention next to Fromm. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, with folder, looks on.

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg and Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived." (10)

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (11)

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (12)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon and General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. (13)

Rudolf Schmundt died of his wounds on 1st October, 1944.

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

General Schmundt, Hitler's chief adjutant, had picked Count Stauffenberg to serve as Fromm's chief of staff and to inject some force into the work of the flagging general. As Schmundt explained to me, Stauffenberg was considered one of the most dynamic and competent officers in the German army. Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg. In spite of his war injuries (he had lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers of his left hand), Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic and at the same time precise, thus showing the marks of the two major and seemingly incompatible educational influences upon him: the circle around the poet Stefan George and the General Staff. He and I would have hit it off even without Schmundt's recommendation. After the deed which will forever be associated with his name, I often reflected upon his personality and found no phrase more fitting for him than this one of Holderlin's :"An extremely unnatural, paradoxical character unless one sees him in the midst of those circumstances which imposed so strict a form upon his gentle spirit."

There were further sessions of these conferences on July 6 and 8. Along with Hitler, Keitel, Fromm, and other officers sat at the round table by the big window in the Berghof salon. Stauffenberg had taken his seat beside me, with his remarkably plump briefcase. He explained the Valkyrie plan for committing the Home Army. Hitler listened attentively and in the ensuing discussion approved most of the proposals. Finally, he decided that in military actions within the Reich the military commanders would have full executive powers, the political authorities - which meant principally the Gauleiters in their capacity of Reich Defense Commissioners-only advisory functions. The military commanders, the decree went, could directly issue all requisite instructions to Reich and local authorities without consulting the Gauleiters.

Whether by chance or design, at this period most of the prominent military members of the conspiracy were assembled in Berchtesgaden. As I know now, they and Stauffenberg had decided only a few days before to attempt to assassinate Hitler with a bomb kept in readiness by Brigadier General Stieff. On July 8, I met General Friedrich Olbricht to discuss the drafting of deferred workers for the army; up to now Keitel and I had been at odds over this question. As so often. Olbricht complained again about the difficulties that inevitably arose from the armed forces being split into four services. Were it not for the jealousies of the different branches, the army could avail itself of hundreds of thousands of young soldiers now in the air force, he said.

The next day, I met Quartermaster General Eduard Wagner at the Berchtesgadener Hof, along with General Erich Fellgiebel of the Signal Corps, General Fritz Lindemann, aide to the chief of staff, and Brigadier General Helmut Stieff, chief of the Organizational Section in the High Command of the Army (OKH). They were all members of the conspiracy and none of them was destined to survive the next few months. Perhaps because the long-delayed decision to attempt the coup d'etat had now been irrevocably taken, they were all in a rather reckless state of mind that afternoon, as men often are after some great resolution. My Office Journal records my astonishment at the way they belittled the desperate situation at the front: "According to the Quartermaster General, the difficulties are minor.... The generals treat the eastern situation with a superior air, as if it were of no importance."

(2) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

Stauffenberg flew from Berlin during the morning and was expected to report on the creation of new Volksgrenadier divisions. He brought his papers with him in a brief-case in which he had concealed the bomb fitted with a device for exploding it ten minutes after the mechanism had been started. The conference was already proceeding with a report on the East Front when Keitel took Stauffenberg in and presented him to Hitler. Twenty-four men were grouped round a large, heavy oak table on which were spread out a number of maps. Neither Himmler nor Goring was present. The Fuhrer himself was standing towards the middle of one of the long sides of the table, constantly leaning over the table to look at the maps, with Keitel and Jodl on his left. Stauffenberg took up a place near Hitler on his right, next to a Colonel Brandt. He placed his brief-case under the table, having started the fuse before he came in, and then left the room unobtrusively on the excuse of a telephone call to Berlin. He had been gone only a minute or two when, at 12.42 p.m., a loud explosion shattered the room, blowing out the walls and the roof, and setting fire to the debris which crashed down on those inside.

In the smoke and confusion, with guards rushing up and the injured men inside crying for help, Hitler staggered out of the door on Keitel's arm. One of his trouser legs had been blown off; he was covered in dust, and he had sustained a number of injuries. His hair was scorched, his right arm hung stiff and useless, one of his legs had been burned, a falling beam had bruised his back, and both ear-drums were found to be damaged by the explosion. But he was alive. Those who had been at the end of the table where Stauffenberg placed the brief-case were either dead or badly wounded. Hitler had been protected, partly by the table-top over which he was leaning at the time, and partly by the heavy wooden support on which the table rested and against which Stauffenberg's brief-case had been pushed before the bomb exploded.