James VI of Scotland and James I of England

James, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots and Henry Darnley, was born in Edinburgh Castle on 19th June, 1566. James's birth occurred three months after the conspiracy which led to the savage murder in Mary's presence of her Italian favourite David Rizzio, which she chose to believe was aimed at her own life, and that of her unborn son. (1)

After the birth of their son the couple lived apart. Lord Darnley was taken ill (officially with smallpox, possibly in fact with syphilis) and was convalescing in a house called Kirk o' Field. Mary visited him daily, so that it appeared a reconciliation was in progress. In the early hours of the morning on 10th February, 1567, an explosion devastated the house, and Darnley was found dead in the garden. There were no visible marks of strangulation or violence on the body and so it was suggested that he had been smothered. Rumours began to circulate that James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell and his friends had arranged his death.

Elizabeth wrote to Mary: "I should ill fulfil the office of a faithful cousin or an affectionate friend if I did not... tell you what all the world is thinking. Men say that, instead of seizing the murderers, you are looking through your fingers while they escape; that you will not seek revenge on those who have done you so much pleasure, as though the deed would never have taken place had not the doers of it been assured of impunity. For myself, I beg you to believe that I would not harbour such a thought." (2)

One of Mary's biographer's, Julian Goodare, claims that the murder was an "abiding historical whodunnit, generating a mass of contradictory evidence, and with a large cast of suspects since almost everyone had a motive to kill him." He points out that historians are divided about Mary's involvement in the killing. "The extreme anti-Mary case is that from late 1566 onwards she was conducting an illicit love affair with Bothwell, with whom she planned the murder. The extreme pro-Mary case is that she was wholly innocent, knowing nothing of the business. In between these two extremes, it has been argued that she was aware in general terms of plots against her husband, and perhaps encouraged them." (3)

According to the depositions of four of Bothwell's retainers, he had been responsible for placing the gunpowder in Darnley's lodgings and had returned at the last moment to make sure that the fuse was lit. According to his biographer, that there is little doubt that Bothwell played a principal part in the murder. (4) Mary's critics point out that she made no attempt to investigate the crime. When urged to do so by Darnley's father, she replied that Parliament would meet in the spring and they would look into the matter. Meanwhile she gave Darnley's clothes to Bothwell. The trial of Bothwell took place on 12th April, 1567. Bothwell's men, estimated at 4,000, thronged the streets surrounding the court-house. Witnesses were too frightened to appear and after a seven-hour trial, he was found not guilty. A week later, Bothwell managed to convince more than two dozen lords and bishops to sign the Ainslie Tavern Bond, in which they agreed to support his aim to marry Mary. (5)

On 24th April, 1567, Mary was abducted by Lord Bothwell and taken to Dunbar Castle. According to James Melville, who was in the castle at the time, later wrote that Bothwell "had ravished her and lain with her against her will". However, most historians do not believe that she was raped and argue that the abduction was arranged by Mary. Bothwell divorced his wife, Jean Gordon, and on 15th May, he married Mary at a protestant ceremony. (6)

People were shocked that Mary could marry a man accused of murdering her husband. Murder placards began appearing in Edinburgh, accusing both Mary and Bothwell of Darnley's death. Several showed the queen as a mermaid, the symbol for a prostitute. Her senior advisors in Scotland claimed that that they were unable to see the queen without Bothwell being present, and alleging that he was virtually keeping her prisoner. Rumours circulated that Mary was bitterly unhappy, repelled by her new husband's boorish behaviour, and overcome with remorse at having contracted a protestant marriage. (7)

Abdication of Mary, Queen of Scots

Twenty-six Scottish peers, turned against Mary and Bothwell, raising an army against them. Mary and Bothwell confronted the lords at Carberry Hill on 15th June, 1567. Clearly outnumbered, Mary and Bothwell surrendered. Bothwell was driven into exile and Mary was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle. While in captivity Mary miscarried twins. Her captors discussed several options: "conditional restoration; enforced abdication and exile; enforced abdication, trial for murder, and life imprisonment; enforced abdication, trial for murder, and execution". (8)

On 24th July she was presented with deeds of abdication, telling her that she would be killed if she did not sign. She eventually agreed to abdicate in favour of her son James. Mary's illegitimate half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, was made regent. James was crowned as a protestant, still only thirteen months old, on 29th July, 1567, at Stirling parish church. The sermon at the coronation was preached by John Knox. In accordance with the religious beliefs of most of the Scottish ruling class, James was brought up as a member of the Protestant Church of Scotland. (9)

The Earl of Moray had no desire to keep the 24-year-old queen in prison for the rest of her life. On 2nd May 1568, she escaped from Lochleven Castle. She managed to raise an army of 6,000 men but was defeated at the Battle of Langside on 13 May. Three days later she crossed the Solway Firth in a fishing boat and landed at Workington. On 18 May, local officials took her into protective custody at Carlisle Castle. (10)

Queen Elizabeth was in a difficult position. She did not want the Catholic claimant to the English throne living in the country. At the same time she could not use her military forces to reimpose Mary's rule on the protestant Scots; nor could she allow Mary to take refuge in France and Spain, where she would be used as a "valuable pawn in the power game against England". There was no alternative but to keep the Queen of Scots in honourable captivity and in 1569 she was sent to Tutbury Castle under the guardianship of the George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. (11) Mary was permitted her own domestic staff and her chambers were decorated with fine tapestries and carpets. (12)

King James and Duke of Lennox

In 1570 George Buchanan was selected as James' tutor. Buchanan sought to turn James into a God-fearing, Protestant king who accepted the limitations of monarchy. Buchanan made every effort to turn James against his mother. He also subjected James to regular beatings. Jenny Wormald claims that Buchanan did this with a "fair degree of sadism" and this was "not just a matter of discipline but of satisfaction". (13)

At the age of 13, the young king came under the influence of Esmé Stewart, the son of John Stewart, 5th Lord of Aubigny, and a Roman Catholic. Maurice Ashley suggests that Stewart encouraged his "adolescent, homosexual feelings". (14) Another source argued that Lennox "went about to draw the King to carnal lust". (15)

James appointed Stewart to the Privy Council and in August 1581, he was granted the title, the Duke of Lennox. Lennox was loathed as a pro-French Catholic who enjoyed all too much of the king's favour. Such was his power, Lennox, managed to arrange the execution of the regent, James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton. James was kidnapped by William Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie, and Lennox was banished from Scotland. (16)

James was released in June 1583, and over the next few years he gradually assumed control of his kingdom. In 1584 he passed the Black Acts, making the king the head of the Church. In future, the government of the Church was to be in the hands of bishops appointed by the crown, and ministers were forbidden to discuss affairs of state from the pulpit. In 1586 he signed a treaty with Queen Elizabeth. It was agreed that James should receive a pension of £4,000 a year. Elizabeth also promised James that as long as he did not "show himself to be unworthy" he would on her death become king of England. (17)

Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots was accused of being involved in a conspiracy led by Anthony Babington to overthrow Queen Elizabeth. Mary's trial took place at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire on 14th October 1586. A commission of thirty-four, consisting of councillors, peers and judges, was convened. She was charged with being an accessory to the attempted murder of Elizabeth. At first she refused to attend the trial unless it were understood that she did so, not as a criminal and not as one subject to English jurisdiction. Elizabeth was furious and wrote to Mary stating: "You have in various ways and manners attempted to take my life and to bring my kingdom to destruction by bloodshed.... These treasons will be proved to you and all made manifest. It is my will that you answer the nobles and peers of the kingdom as if I were myself present... Act plainly without reserve and you will the sooner be able to obtain favour of me." (18)

During the trial Mary accused Francis Walsingham of engineering her destruction by falsifying evidence. He rose to his feet and denied this: "I call God to witness that as a private person I have done nothing unbeseeming an honest man, nor, as I bear the place of a public man, have I done anything unworthy of my place. I confess that being very careful for the safety of the queen and the realm, I have curiously searched out all the practices against the same." (19)

Julian Goodare has argued that the plot was a frame-up: "A channel of communication with Mary was arranged, with packets of coded letters hidden in beer barrels; unknown to the plotters, Walsingham saw all Mary's correspondence. The plot was thus a frame-up, a point of which Mary's defenders sometimes complain. It is not, however, obvious that the English government was obliged to nip the plot in the bud to prevent Mary from incriminating herself. The frame-up was directed almost as much against Elizabeth as against Mary." (20)

The trial was moved to Westminster Palace on 25th October, where the 42-man commission, including Walsingham, found Mary guilty of plotting Elizabeth's assassination. As Walsingham had expected, Elizabeth proved reluctant to execute her rival and prevented a public verdict being decided after the trial. Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued that Elizabeth feared that Mary's execution might precipitate the rebellion or invasion which everybody feared. "To kill Mary was also foreign to Elizabeth's accustomed clemency and to her native fear of drastic action." (21)

Parliament petitioned for Mary's execution. Elizabeth hesitated and as always she hoped to shift the responsibility for action on to others and "hinted that Mary's murder would not be displeasing to her". (22) However, her government ministers refused to take action until he had written instructions from Elizabeth. On 19th December 1586, Mary wrote a long letter to Elizabeth arguing that she had been unjustly condemned by those who had no jurisdiction over her, and that she had "a constant resolution to suffer death for upholding the obedience and authority of the apostolical Roman church." (23)

Parliament devised two bills: one to execute Mary for high treason, the other to say she was incapable of succession to the English throne. The first of these she rejected and the second she promised to consider. William Cecil told Walsingham that the House of Commons and the House of Lords were both determined on the only sensible course "but in the highest person, such slowness... such stay in resolution." Elizabeth stated to Walsingham and Cecil "Can I put to death the bird that, to escape the pursuit of the hawk, has fled to my feet for protection? Honour and conscience forbid!"

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) has pointed out that she had ordered no execution by beheading since that of Thomas Howard, the 4th Duke of Norfolk, in 1572: "Since she came to the throne, Elizabeth had ordered no execution by beheading. After fourteen years of disuse, the scaffold on Tower Hill was falling to pieces, and it was necessary to put up another. The Duke's letters to his children, his letters to the Queen, his perfect dignity and courage at his death, made his end moving in the extreme, and he could at least be said that no sovereign had ever put a subject to death after more leniency or with greater unwillingness." (24)

Mary was informed on the evening of 7th February that she was to be executed the following day. She reacted by claiming that she was being condemned for her religion. She mounted the scaffold in the great hall of Fotheringhay, attended by two of her women servants, Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle. The two executioners knelt before her and asked forgiveness. She replied, "I forgive you with all my heart, for now, I hope, you shall make an end of all my troubles." (25)

Mary's last words were "Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit". The first blow missed her neck and struck the back of her head. The second blow severed the neck, except for a small bit of sinew, which the executioner cut through using the axe. He held her head aloft by the hair and declared, "God save the Queen." As he did so the head fell to the ground, revealing that Mary had been wearing a wig had actually had a very short, grey hair. (26)

According to the account written by Robert Wynkfield: "Then one of the executioners, pulling off her garters, espied her little dog which was crept under her cloths, which could not be gotten forth by force, yet afterward would not depart from the dead corpse, but came and lay between her head and her shoulders, which being imbrued with her blood was carried away and washed, as all things else were that had any blood was either burned or washed clean, and the executioners sent away with money for their fees, not having any one thing that belonged unto her. And so, every man being commanded out of the hall, except the sheriff and his men, she was carried by them up into a great chamber lying ready for the surgeons to embalm her." (27)

Anne of Denmark

James was so anxious to become the next king of England that he made no protest when his mother was executed. To reinforce his claim to the throne he decided to get married. Negotiations took place with several European royal families before he selected Anne of Denmark, the fourteen-year-old daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark. A proxy marriage took place in Copenhagen in August 1589. The couple were married formally at the Bishop's Palace in Oslo on 23rd November and they returned to Scotland on 1st May 1590. (28)

Anne was under pressure to provide James and Scotland with an heir, but for the first few years she failed to produce a child. His opponents began to circulate stories of his homosexuality. (29) It was pointed out that the couple did not live together and she rarely accompanied him on royal visits. (30)

There was great public relief when on 19th February 1594, Anne gave birth to her first child, Henry Frederick. It was believed by some that Anne was a secret Roman Catholic and the child was placed in the care of John Erskine, Earl of Mar, a leading Protestant in Scotland. According to Maureen M. Meikle this decision "irrevocably damaged" the relationship between the royal couple. (31)

A daughter, Elizabeth, was born at Dunfermline Palace on 19th August 1596. A second son, Charles, followed on 19th November, 1600. He was created Duke of Albany at his baptism and Duke of York five years later. Charles was a weak and backward child. It was believed that Charles suffered from rickets and he had difficulty walking without assistance. His doctor stated "he was so weak in his joints and especially ankles, insomuch as many feared they were out of joint". (32)

Divine Right of Kings

In 1597 James VI of Scotland began work on Basilikon Doron. This manual on the powers of a king, was written in the form of a letter to his four-year old son, Henry Frederick. This document provides general guidelines to follow to be a good monarch. James argues that a king should govern with justice and equality. He should also invite foreign merchants into the country and base the currency on gold and silver to help the economy grow. James also stated that to be a good monarch he must be well acquainted with his subjects and therefore it would be wise to visit all kingdoms every three years. He also told his son that he should choose a wife that shared the same religion. (33)

James used this document to reinforce the idea that kings were appointed by God and ruled in his name. The Divine Rights of Kings theory had been developed by the French philosopher, Jean Bodin in his book, The Six Books of the Republic (1576). Although he was a Roman Catholic he was critical of papal authority over governments and argued that this abuse of power had helped produce the Protestant Reformation. Bodin believed that the strong central control of a national monarchy would reduce religious conflict. (34)

James explored this idea in more detail in The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598). He rejected the idea that Pope Clement VIII should have any power over his government. James claimed that "kings are justly called gods, for that they exercise a manner or resemblance of divine power upon earth... They make and unmake their subjects; they have power of raising and casting down, of life and of death, judges over all their subjects and yet accountable to none but God only." (35)

King of England

On 24th March, 1603, Archbishop John Whitgift was instructed to visit Queen Elizabeth. The seventy-three year old head of the church knelt by her bed and prayed. After about 30 minutes he attempted to get up but she made a sign that suggested he carried on praying. He did so for another half-hour and when he attempted to rise, the Queen gestured with her hand to keep on the floor. Eventually, she sank into unconsciousness and he was allowed to leave the room. She died later that evening. (36)

It was Robert Cecil who read out the proclamation announcing James as the next king of England on the day Elizabeth died, first at Whitehall and then at the gates to the City of London. The following day James wrote from Edinburgh informally confirming all the privy council in their positions, adding in his own hand to Cecil, "How happy I think myself by the conquest of so wise a councillor I reserve it to be expressed out of my own mouth unto you". (37)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cecil remained in London for a short time, to ascertain that there was no outbreak of trouble in the capital or elsewhere over the change of dynasty, and also to make arrangements for Elizabeth's funeral. (38) On Thursday 28th April, a procession of more than a thousand people made its way from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey. "Led by bell-ringers and knight marshals, who cleared the way with their gold staves, the funeral cortege stretched for miles. First came 260 poor women... Then came the lower ranking servants of the royal household and the servants of the nobles and courtiers. Two of the Queen's horses, riderless and covered in black cloth, led the bearers of the hereditary standards... The focal point of the procession was the royal chariot carrying the Queen's hearse, draped in purple velvet and pulled by four horses... On top of the coffin was the life-size effigy of Elizabeth... Sir Walter Raleigh and the Royal Guard walking five abreast, brought up the rear, their halberds held downwards as a sign of sorrow." (39)

King James, aged thirty-seven, left for England on 26th March 1603. When he arrived at York his first act was to write to the English Privy Council for money as he was deeply in debt. His demands were agreed as they were anxious to develop a good relationship with their king who looked like a promising new leader. "James's quick brain, his aptitude for business, his willingness to take decisions, right or wrong, were welcome enough after Elizabeth's tedious procrastination over trifles. They were charmed, too, by his informal bonhomie." (40)

Discussions began on the way that the two kingdoms would unite. The English view was that Scotland should be incorporated into England, the Scottish that the two kingdoms should be equal partners. The historian, Sir Robert Cotton, produced a pamphlet where he attempted to justify the union of the two countries. It was "a treatise extolling the name of Britain; as in the past smaller kingdoms had joined to become the kingdoms of England, France, and Spain, so now the smaller kingdoms within the British Isles would come together under the ancient name of Britain." (41)

When he opened his first Parliament in March 1604 James reminded members that he was the descendant of the royal houses of both York and Lancaster. "But the union of these two princely houses is nothing comparable to the union of two ancient and famous kingdoms, which is the other inward peace annexed to my person." One member of Parliament, Sir Christopher Pigott, made it quite clear that he was opposed to a union of the two countries. He told the House of Commons the Scots were "beggars, rebels and traitors" who had murdered all the kings. James was furious and ordered him to be sent to the Tower of London. (42)

In November 1604 James VI wrote to Cecil complaining that English officials did not welcome the Scots, for they feared loss of office for themselves. He decided against giving Scotsmen senior posts in his administration. (43) However, he did plan to reward his followers and a total of 158 Scotsman were given positions in his government and household. (44)

Robert Cecil led the successful negotiations with the envoys of Philip III of Spain. The peace brought great benefits to English trade, despite occasional objections from English merchants trading to Spain, who found conditions there much harder than they expected. It enhanced the prosperity of both London and the other ports in England. The 1604 treaty allowed Englishmen to trade and settle in the West Indies and North America. Cecil was rewarded by being given the title of Viscount Cranborne. The following year he became the Earl of Salisbury. (45)

The Gunpowder Plot

Soon after arriving in London, James told Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, "as for the catholics, I will neither persecute any that will be quiet and give but an outward obedience to the law, neither will I spare to advance any of them that will by good service worthily deserve it." James kept his promise and the catholics enjoyed a degree of tolerance that they had not known for a long time. Catholics now became more open about their religious beliefs and this resulted in accusations that James was not a committed Protestant. (46) The king responded by ordering in February 1605, the reintroduction of the penal laws against the catholics. It has been estimated that 5,560 people were convicted of rucusancy during this period. (47)

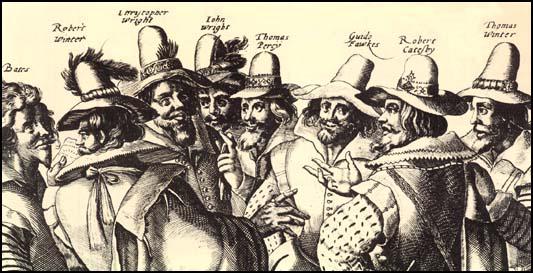

The catholics felt bitter at the collapse of all their hopes. They now realised that they were an isolated minority in a hostile community. In February 1604, Robert Catesby devised the Gunpowder Plot, a scheme to kill James and as many Members of Parliament as possible. At a meeting at the Duck and Drake Inn on 20th May, Catesby explained his plan to Guy Fawkes, Thomas Percy, John Wright and Thomas Wintour. All the men agreed under oath to join the conspiracy. Over the next few months Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates and Christopher Wright also agreed to take part in the overthrow of the king. (48)

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November, 1605. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when Thomas Percy was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The conspirators also hoped to kidnap the king's daughter, Elizabeth. In time, Catesby was going to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman. (49)

One of the people involved in the plot was Francis Tresham. He was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November. Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament. While searching the cellars below the House of Lords they found Guy Fawkes and the gunpowder. Fawkes claimed he was John Johnson, the servant of Thomas Percy. (50)

Guy Fawkes was tortured and admitted that he was part of a plot to "blow the Scotsman (James) back to Scotland". On the 7th November, after enduring further tortures, Fawkes gave the names of his fellow conspirators. Fawkes, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates, and Thomas Wintour, were all hanged, drawn and quartered. (51)

This is the traditional story of the Gunpowder Plot. However, in recent years some historians have begun to question this version of events. Some have argued that the plot was really devised by Sir Robert Cecil. This version claims that Cecil blackmailed Catesby into organising the plot. It is argued hat Cecil's aim was to make people in England hate Catholics. For example, people were so angry after they found out about the plot, that they agreed to Cecil's plans to pass a series of laws persecuting Catholics. (52)

Cecil's biographer, Pauline Croft, has argued that this is unlikely to have been true: "In the inflamed atmosphere after November 1605, with wild accusations and counter-accusations being traded by religious polemicists, there were allegations that Cecil himself had devised the Gunpowder Plot to elevate his own importance in the eyes of the king, and to facilitate a further attack on the Jesuits. Numerous subsequent efforts to substantiate these conspiracy theories have all failed abysmally." (53)

Robert Cecil definitely took advantage of the situation. Henry Garnett, head of the Jesuit mission in England, was arrested. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "The evidence against him was largely circumstantial, but the government was determined to tar all the missionary priests with the brush of sedition in the hope of thereby depriving them of the support of the lay catholic community. A further step in this direction came in 1606, with the drawing up of an oath of allegiance which all catholics were required to take." (54)

The failed Gunpowder Plot united the nation. The anniversary of 5th November became an annual holiday. In the Parliament that followed the conspiracy James obtained a vote of subsidies and other levies amounting to about £450,000. In April, 1606, James managed to persuade Parliament to accept that the newly designed Union Jack flag would be flown on British ships. English ships would continue to fly the St George's cross, whereas Scottish ones would still use the St Andrew flag. (55)

Prince of Wales

James's eldest son, Henry Frederick, aged 18, died of typhoid fever, on 6th November, 1612. His younger brother Charles succeeded him as heir apparent to the English, Irish and Scottish thrones. Charles had been educated by a Scottish Presbyterian tutor, and mastered Latin and Greek and showed an aptitude for modern languages. Charles was a shy and reserved boy who never overcame a stammer. (56)

At this time James had grown close to Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Charles Howard, Lord of Effingham. All these men were all sympathetic to the Roman Catholic church. Members of the Howard family suggested that Charles should marry Maria Anna, the youngest daughter of King Philip III of Spain. According to John Philipps Kenyon, the author of The Stuarts (1958): "They urged James to marry his son to the daughter of Philip III of Spain and use her huge dowry to pay off his debts, with the ultimate aim of reconciling the English church with Rome." (57)

The English Parliament was actively hostile towards Spain and Catholicism, and when called by James in 1621, the members hoped for an enforcement of recusancy laws, a naval campaign against Spain, and a Protestant marriage for the Prince of Wales. (58) Francis Bacon, the Lord Chancellor, led the campaign against the proposed marriage and along with other MPs suggested that Charles should be married to a Protestant princess. James insisted that the House of Commons be concerned exclusively with domestic affairs and should not be involved in making decisions about foreign policy. (59)

The king's supporters responded by accusing Bacon of bribery and corruption and he was impeached before the House of Lords. Not since the fifteenth century had a great officer of the crown been overthrown in Parliament. (60) Bacon was fined £40,000 and "imprisonment at the king's pleasure". He was also barred from any office or employment in the state and forbidden to sit in parliament or come within the verge (12 miles) of the court. The fine was never collected and his imprisonment in the Tower of London lasted only three days. (61)

James refused to accept defeat and he arranged for Charles to be tutored in Spanish and the latest continental dance steps. In February 1623, he travelled incognito with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, to Madrid, to meet members of the Spanish royal family. He was described as having "grown into a fine gentleman" but it was also observed that he looked undistinguished and was only five feet four inches tall. (62) During this period Charles was strongly influenced by Buckingham's political ideas. (63)

John Morrill has pointed out: "Charles's decision to undertake a personal courtship as a way of breaking through the diplomatic deadlock was an indication of his growing self-confidence. He was now commonly acting as a political agent, meeting with privy councillors, foreign ambassadors, and the duke of Buckingham, sometimes under his father's instructions, sometimes independently. The decision to travel to Spain and conduct face-to-face negotiations to conclude his marriage was a further step in his maturation." (64)

The Spanish negotiators demanded that Charles convert to Roman Catholicism as a condition of the match. They also insisted on toleration of Catholics in England and the repeal of the penal laws. After the marriage Maria Anna would have to stay in Spain until England complied with all the terms of the treaty. Charles knew that Parliament would never accept this deal and he returned to England without a bride. (65)

It was now decided to change foreign policy and James now opened up talks about the possibility of an alliance with Louis XIII of France that involved the marriage of Charles to Henrietta Maria, the king's sister. It was unprecedented for a Catholic princess to be married to a Protestant. Pope Urban VIII only gave his permission when he was assured that the treaty signed in November 1624 included "commitments about religious rights of the queen, her children, and her household; while in a separate secret document Charles promised to suspend operation of the penal laws against Catholics". (66)

In February 1624, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, managed to persuade most members of Parliament to the new anti-Spanish policy and to negotiate a treaty with France. However, it was not explained to Parliament that the proposed marriage would involve increased toleration for Roman Catholics. (67)

These negotiations resulted in Parliament losing confidence in King James. They no longer trusted him and he was forced into making several concessions. This included a Monopoly Act, which forbade royal grants of monopolies to individuals. James also agreed to work closely with Parliament to deal with the economic crisis that the country was experiencing at the time. (68)

James VI of Scotland and James I of England, died on 27th March 1625. The new king, Charles I, married fifteen-year-old Henrietta Maria by proxy at the church door of Notre Dame on 1st May. Many members of the House of Commons were opposed to the king's marriage to a Roman Catholic, fearing that it would undermine the official establishment of the reformed Church of England. The Puritans were particularly unhappy when they heard that the king had promised that Henrietta Maria would be allowed to practise her religion freely and would have the responsibility for the upbringing of their children until they reached the age of 13. When the king was crowned on 2nd February 1626 at Westminster Abbey, his wife was not at his side as she refused to participate in a Protestant religious ceremony. (69)

Primary Sources

(1) Jenny Wormald, King James I : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Throughout his life James was a remarkable phenomenon: a king with an enormous literary output. In this he was unrivalled. Unlike Henry VIII he was his own polemicist; unlike Elizabeth, far more than a translator. His range is astonishing: the poet-king and writer of poetic theory; the new David, with his translation of the Psalms; the theologian; the political theorist as well as practising politician; the speech and letter writer on a huge scale. His harsh education failed to discourage his love of the things of the mind; the king famed to this day for his passion for hunting was, in his own time, equally famed for his passion for retiring into his study for solace and as an escape from relentless and importunate suitors. Several of his holograph manuscripts survive. Perhaps none gives so evocative a picture of the scholar-king as the manuscript of his Basilikon Doron. Though it is impressively bound in purple velvet, with the royal initials, the Scottish lion and the thistles stamped on the binding in gold leaf, the inside is a wonderful comedown, a mess such as no teacher or publisher would accept today; the opening of every section reflects graphically the problem of getting started, with the erasures, the inserted scrawls, before the words begin to flow, and all written on sheets which owe nothing to modern standardization of paper size.

(2) John Philipps Kenyon, The Stuarts (1958)

At the age of twenty-two George Villiers had that rather over-ripe masculine attraction that trembles on the verge of feminity: tall and beautifully-proportioned, he had a heart-shaped face framed in dark chestnut hair and short beard, an exquisitely-curved mouth, and the dark blue eyes of the highly-sexed...

His intelligence, while it existed at a low level, undoubtedly existed... Buckingham's boyish flirtatiousness enabled him to cross James with impuunity, emerging rather with enhanced influence; his letters bubble with nonsensical charm and lovers' baby-talk, but there is a pertness even in his unvarying valediction.

(3) King James I, speech at meeting of the Privy Council (September 1617)

I, James, am neither God nor an angel, but a man like any other. Therefore I act like a man, and confess to loving those dear to me more than other men. You may be sure that I love the Earl of Buckingham more than anyone else, and more than you who are here assembled. I wish to speak in my own behalf, and not to have it thought to be a defect, for Jesus Christ did the same, and therefore I cannot be blamed. Christ had his John, and I have my George.

(4) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

As King of Scotland, James had come into conflict with the more extreme presbyterians, who maintained that the Church was entirely separate from the state and that the secular ruler had no authority over it. And, from the other end of the religious spectrum, he had been reminded by Roman Catholics that all earthly sovereigns were subordinate to God and therefore to God's deputy on earth, the Pope. James countered these implicit threats to his independence by asserting the divine origin of kingly authority and in his writings as in his speeches he consciously and deliberately exalted monarchical power.

There was nothing new in James's belief that kings were appointed by God and ruled in His name. The "godly prince" had been the Reformation's substitute for papal authority, and Elizabeth, no less than James, had taken it for granted that her office was of divine origin.... James's insistence on his divine right to rule seemed to imply that the liberties of his subjects only existed upon sufferance, and this was something which the political nation, the propertied section of English society, would never accept.

Student Activities

The Gunpowder Plot (Answer Commentary)

Military Tactics in the English Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Women in the English Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Portraits of Oliver Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Execution of King Charles I (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)