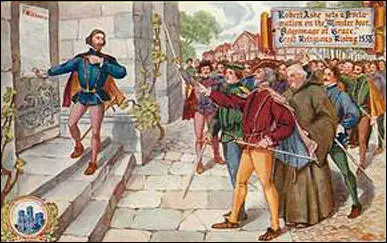

Classroom Activity on Robert Aske

Robert Aske, the third son of Sir Robert Aske was born in about 1500. His father was a large landowner, from Aughton, near Selby, Yorkshire. He was admitted to Gray's Inn and was trained as a lawyer. He was travelling to London on 4th October 1536 when he was captured by a group of rebels involved in an uprising that had started in the market town of Louth in Lincolnshire, concerning the decision to close the monasteries in that area.

Robert Aske agreed to use his talents as a lawyer to help the rebels. He agreed to use his talents as a lawyer to help the rebels. He wrote letters for them explaining their complaints. These letters insisted that their quarrel was not with the King or the nobility, but with the government of the realm, especially Thomas Cromwell.

Robert Aske arrived at Pontefract Castle on 20th October. After a short siege, Thomas Darcy, running short of supplies, surrendered the castle. After discussions with Aske, Darcy decided to join the Pilgrimage of Grace. He swore the oath presented to him by Aske.

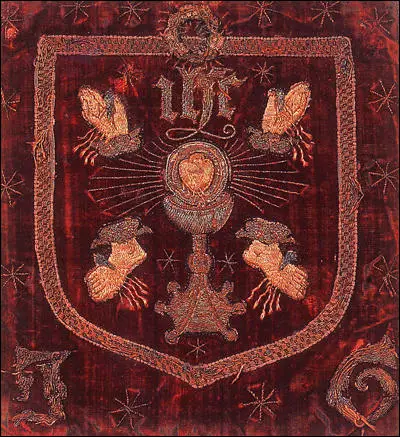

Aske offered the leadership of the Pilgrimage of Grace to Darcy. He refused but agreed to provide soldiers for the cause. To show his commitment to the new allegiance, one of his first acts was to send the oath that he signed into Lancashire. He also arranged for flags to be made that included the religious insignia of the Five Wounds of Christ (it depicted a bleeding heart above a chalice, both being surrounded at the corners by the pierced hands and feet).

Primary Sources

(Source 2) Robert Aske made a speech about the Pilgrimage of Grace in York in October 1536.

We have taken (this pilgrimage) for the preservation of Christ's church, of this realm of England, the King our sovereign lord, the nobility and commons of the same... the monasteries... in the north parts (they) gave great alms to poor men and laudably served God... and by occasion of the said suppression the divine service of Almighty God is much diminished.

(Source 3) Robert Aske, Pilgrimage of Grace Oath (October, 1536)

Ye shall not enter into this our Pilgrimage of Grace for the Commonwealth, but only for the love that ye do bear unto Almighty God, his faith, and to Holy Church militant and the maintenance thereof, to the preservation of the King's person and his issue, to the purifying of the nobility, and to expulse all villein blood and evil councillors against the commonwealth from his Grace and his Privy Council of the same. And ye shall not enter into our said Pilgrimage for no particular profit to your self, nor to do any displeasure to any private person, but by counsel of the commonwealth, nor slay nor murder for no envy, but in your hearts put away all fear and dread, and take afore you the Cross of Christ, and in your hearts His faith, the Restitution of the Church, the suppression of these Heretics and their opinions, by all the holy contents of this book.

(Source 4) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

While an uneasy calm was settling on Lincolnshire a far more serious revolt broke out in Yorkshire, where the initiative was taken by Robert Aske, a minor gentleman and lawyer. Aske was an idealist, who gave to the rebellion most of its spiritual quality... His loyalty to the King was genuine, and he and Henry probably shared many of the same assumptions about religion.

(Source 6) Anthony Fletcher, Tudor Rebellions (1974)

Aske's intention throughout the campaign he directed was to overawe the government into granting the demands of the north, by presenting a show of force. Only one man was killed during the Pilgrimage. He did not want to advance south unless Henry refused the Pilgrims' petition and he had no plan to form an alternative government or remove the king. Aske merely wanted to give the north a say in the affairs of the nation, to remove Cromwell and reverse certain policies of the Henrician Reformation.

(Source 7) Peter Ackroyd, Tudors (2012)

On Friday 15 December the king sent a message to Robert Aske by means of one of the gentlemen of the privy chamber. He wrote that he had a great desire to meet Aske, to whom he had just offered a free pardon, and to speak frankly about the cause and the course of the rebellion. Aske welcomed the opportunity of exonerating himself. As soon as Aske entered the royal presence the king rose up and threw his arms around him. "Be you welcome, my good Aske; it is my wish that here, before my council, you ask what you desire and I will grant it."

Aske replied: "Sir, your majesty allows yourself to be governed by a tyrant named Cromwell. Everyone knows that if it had not been for him the 7,000 poor priests I have in my company would not be ruined wanderers as they are now."

The king then gave the rebel a jacket of crimson satin and asked him to prepare a history of the previous few months. It must have seemed to Aske that the king was in implicit agreement with him on the important matters of religion. But Henry was deceiving him. He had no intention of halting or reversing the suppression of the monasteries; he had no intention of repealing any of the religious statutes in force.

(Source 9) Jasper Ridley, Henry VIII (1984)

Aske spent Christmas at Greenwich as Henry's guest. Henry was very friendly, and Aske was flattered, charmed and completely fooled.... Within a few days, a revolt broke out in the East Riding. It was led by Sir Francis Bigod, which was a little surprising, for Bigod had been an active anti-Papist, and had hitherto played no part in the Pilgrimage of Grace. He tried to capture Hull, but was repulsed by the citizens. The rising was immediately condemned by Aske, Darcy and Constable, who did all they could to prevent it from spreading, for they feared that it would result in the withdrawal of the concessions which they had obtained from Henry... They also played an active part in suppressing the rising.

(Source 10) Sentence of death passed on Robert Aske (July, 1537)

You are to be drawn upon a hurdle to the place of execution, and there you are to be hanged by the neck, and being alive cut down, and your privy-members to be cut off, and your bowels to be taken out of your belly and there burned, you being alive; and your head to be cut off, and your body to be divided into four quarters, and that your head and quarters to be disposed of where his majesty shall think fit.

(Source 11) Geoffrey Moorhouse, The Pilgrimage of Grace (2002)

When Aske was brought out his cell that Thursday morning at York, before he was tied to the hurdle that would take him to the scaffold, he confessed that he had offended God, the King and the world. He was then dragged through the centre of the city, "desiring the people ever as he passed by to pray for him." When he was taken from the hurdle he was led up the mound and into Clifford's Tower for a little while, until the Duke of Norfolk arrived. On being brought out again he was given the opportunity, like all condemned men, to make a final statement to the watching crowd. And in this he said that there were two things which had aggrieved him. One was that Cromwell had sworn that all northern men were traitors, "wherewithal he was somewhat offended". The other was that the Lord Privy Seal "sundry times promised him a pardon of his life, and at one time he had a token from the King's Majesty of pardon for confessing the truth". In reporting this, Coren added, "These two things he showed to no man in these North parts, as he said, but to me only; which I have and will ever keep secret." As soon as Norfolk was ready for the spectacle, Aske climbed to the gallows on top of the tower, asked for forgiveness again... When they had finished butchering his body, it was hung there in chains; and John Aske, summoned with others of the Yorkshire gentry to be present, was one of those who watched all the things they did to his youngest brother.

Questions for Students

Question 1: Compare the value of sources 1 and 5 to the historian.

Question 2: Read sources 2 and 3. What do they tell us about Robert Aske's views on the monasteries and on the behaviour he expected from people who joined the Pilgrimage of Grace.

Question 3: Compare the views of the historians, Roger Lockyer (source 4) and Anthony Fletcher (source 6) on Robert Aske.

Question 4: Read the introduction and study source 8. Why do you think the Five Wounds of Christ flag was carried in the Pilgrimage of Grace march in Yorkshire?

Question 5: Read sources 7 and 9 and then explain Jasper Ridley's words: "Aske spent Christmas at Greenwich as Henry's guest. Henry was very friendly, and Aske was flattered, charmed and completely fooled."

Question 6: Why did Henry VIII decide to have Robert Aske "hung, drawn and quartered"? It will help you to read sources 10 and 11.

Answer Commentary

A commentary on these questions can be found here

Download Activity

You can download this activity in a word document here

You can download the answers in a word document here