Dissolution of the Monasteries

The first monasteries (religious houses) in England were formed in the 6th century. The Viking invasions destroyed most monastic communitites and by the 10th century monasticism was almost extinct. However, most of the Normans who arrived with William the Conqueror in 1066 were devout Christians. Norman landowners gave a considerable amount of money for the building of churches and monasteries in England. Over the next few years a large of monks arrived in England from Normandy.

Trevor Rowley, the author of The Norman Heritage: 1066-1200 (1983) has pointed out: "The first to arrive were the Norman monks from the Conqueror's duch, many of them were men who combined native energy and organizational ability with the zeal of a new and fervent religious movement. Some of them were carefully chosen to govern the existing monasteries, while others came to colonize the new foundations such as Chester and Battle... Some came to to reinforce existing communities and their daughter-houses at Canterbury, Rochester and Colchester." (1)

Norman Monasteries

These monasteries followed the rules of St. Benedict, who had established several monasteries in Italy in the 6th century. One rule was that they had to pray eight times a day. Another rule was that they should work with their hands. The monks were encouraged to work in the fields, as well as doing their own cooking, washing and cleaning. Benedictine monks were instructed to eat two simple meals a day and were not allowed to eat expensive food such as meat. The monks were also told that they should not spend their time talking to each other. A prosperous monk would be expected to donate all his personal wealth to the monastery. While in the monastery a Benedictine monk had to wear a habit made of dark, coarse, hard-wearing material. (2)

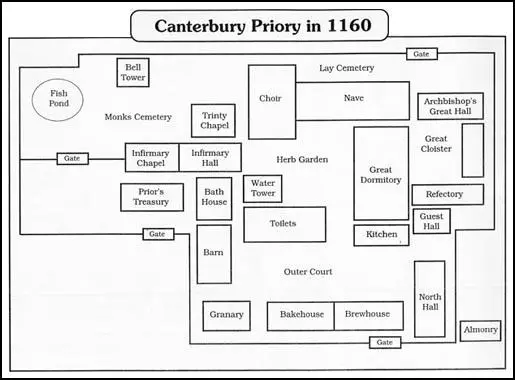

One of the first monasteries built by the Normans was Canterbury Priory. With the support of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, it soon became one of the most important monasteries in England. Lanfranc left instructions that all future Archbishops of Canterbury should be elected by the monks of Canterbury Priory. "Lanfranc had a basic concern that monks should establish their way of life according to the best ancient models and that stability, obedience, oversight, and poverty should be rigorously ensured." (3)

When rich Normans died they often left some of their money and land to monasteries. People were especially generous to Canterbury Priory. By 1200 Canterbury Priory had been given land in Kent, Essex, Surrey, Suffolk, Norfolk, Devon, Oxfordshire and Ireland. Land owned by Canterbury Priory was a source of great wealth. Twice a year, at Easter and Michaelmas, a monk would travel to the villages owned by Canterbury Priory to collect the rents from their tenants. By the end of the 13th century Canterbury Priory was making a net profit of over £2,000 a year from the land that it owned. The large monasteries accumulated vast endowments in land and tithes. It was claimed that a third of the wealth of England was in the hands of the Church. (4)

Another source of income was the collection of religious relics associated with Thomas Becket. People suffering from diseases and illnesses believed they would be cured if they touched these holy relics. In gratitude, the pilgrims donated money to the priory. In some years it was not unusual for the monastery to receive over a £1,000 from grateful pilgrims.

At the same time Augustinian monasteries were formed. They followed they teachings of St Augustine and were friars rather than monks. Whereas monks lived in an isolated self-sufficient community, friars believed that they should provide a service to a wider society. Dedicated to teaching and evangelism, their small religious houses flourished close to towns and castles, bringing Christianity to the poor and sick. (5) By the end of the twelfth century there were more than 600 monastic institutions of varying beliefs in England. (6)

All monks and nuns took vows of celibacy and wore distinctive habits (a long, loose garment). The main function and first responsibility of every religious house was to maintain the daily cycle of prayer. At least eight times the community would gather to sing or recite prayers. In some monasteries even the hours of sleep were broken by saying prayers at 2 a.m. in the morning.

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, monks were the intellectual leaders of Christendom. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out that the following century saw great changes in education: "The fifteenth 15th century saw great changes the spread of the new learning with its emphasis on classics and philosophy... English education had also shifted its emphasis towards the study of common and civil law. While the pattern of education was changing, so also were assumptions about the Christian life. The place of the Church was held to be in the world, though not of it, and there was no longer any instinctive sympathy with the monastic ideal." (7)

Tudor Monasteries

By the 16th century around two-thirds of the religious houses were small establishments. Many housed only a handful of monks and nuns had no vast estates. Most of the women's houses were like this. Only 17 of over the country's 200 nunneries were of any great size. Even in these smaller houses the standard of spirituality was not very high and vows of chastity were regularly broken. (8)

The monks spent a vast amount of money on food. One visitor was surprised when he discovered that the monks enjoyed sixteen-course meals, including the serving of meat, a food that St. Benedict had forbidden them to eat. The monks were especially fond of fish. The priory accounts show that in some years the monks spent nearly £250 a year on fish. Wine from France was another luxury item that the monks enjoyed.

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The monks employed a large number of servants to look after them. By the end of the 13th century, the accounts reveal that there were more servants in Canterbury Priory than monks. The monks employed people to buy and cook their food, wait on them during dinner, tend their gardens, look after their animals, wash their clothes, and to clean and repair the monastery. The monks also paid actors and musicians to entertain them. According to Roger Lockyer: "Feasting had replaced fasting, dress was extravagant, services were poorly attended... In charity and hospitality the same decline is recorded. Almsgiving may have averaged the stipulated one-tenth of monastic revenues, but it was indiscriminate and did little to relieve the genuine problem of poverty." (9)

At the beginning of the 16th century monasteries owned well over a quarter of all the cultivated land in England. Farmers who rented land from the monks often criticized them for being greedy and uncaring landlords. It was also claimed that the monks had been corrupted by the wealth obtained from renting their land. Religious reformers inspired by the writings of Martin Luther began to criticise the behaviour of the monks and nuns in England.

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was Lord Chancellor and in 1519 he sent "visitors" to various monasteries in order to record the conditions and habits of the monks. The reports suggested that various levels of disorder and abuse were taking place. For example, it was reported that at Peterborough Monastery: "The lord abbot does not choose studious brothers but looks for lazy ones.. He sells wood and has kept the money for himself... He had in his chamber a certain maiden named Joan Turner... The monastery has no beds and other things for receiving guests."

Wolsey punished the principal offenders and sent out strict regulations and statutes to guide future conduct. This included instructing them to obey their vow of celibacy. Wolsey was of course breaking his own guidelines. When he was a young priest he became the father of two illegitimate children. This "did much to fuel the accusations of lechery and fornication so widely levelled at him". He acknowledged and provided for the children, the son, Thomas Wynter, was appointed archdeacon of Suffolk and his daughter, Dorothy, became a nun at Shaftesbury. (10)

As a result of the reports he received he suppressed some twenty-nine monastic houses and used their revenues to finance a school in Ipswich and to establish Cardinal College (now Christ Church) in Oxford. The college was built on the land owned by the Priory of St Frideswide. (11) Wolsey selected a young lawyer, Thomas Cromwell, to arrange the selling the lands and goods owned by the monasteries. (12)

In 1528 Simon Fish published A Supplication for the Beggars. He argued that the clergy should spend their money in the relief of the poor and not amass it for monks to pray for souls. (13) Fish claimed that monks were "ravenous wolves" who had "debauched 100,000 women". He added that the monks were "the great scab" that would not allow the Bible to be published in "your mother tongue". (14)

George M. Trevelyan has argued that this work had an impact on the thinking of Henry VIII: "The conclusion reached by the pamphleteer (Simon Fish) is that the clergy, especially the monks and friars, should be deprived of their wealth for the benefit of the King and Kingdom, and made to work like other men; let them also be allowed to marry and so be induced to leave other people's wives alone. Such crude appeals to lay cupidity, and such veritable coarse anger at real abuses uncorrected down the centuries, had been generally prevalent in London under Wolsey's regime, and at his fall such talk became equally fashionable at Court." (15)

Dissolution of the Monasteries

In January 1535, Thomas Cromwell was appointed as Vicar-General. This made him the King's deputy as Supreme Head of the Church. He had been a secret supporter of religious reformers such as William Tyndale, Robert Barnes, Richard Bayfield, Thomas Bilney, John Bradford, Simon Fish, John Frith, Miles Coverdale, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, John Rogers and Nicholas Shaxton and over the next few years he used his power to make changes to the Church.

On 3rd June 1535, Cromwell sent a letter to all the bishops ordering them to preach in support of the supremacy, and to ensure that the clergy in their dioceses did so as well. A week later he sent further letters to Justices of Peace ordering them to report any instances of his instructions being disobeyed. In the following month he turned his attention to the monasteries. In September he suspended the authority of every bishop in the country so that the six canon lawyers he had appointed as his agents could complete their surveys of the monasteries. (16)

Cromwell provided his agents with eighty-six questions. This included: "Whether the divine service was kept up, day and night, in the right hours?"; "Whether they (monks) kept company with women, within or without the monastery?"; "Whether they had any boys lying by them?; "Whether any of the brethren were incorrigible?" "Whether you do wear your religious habit continually, and never leave it off but when you go to bed?" (17)

At the time there were 563 religious houses in England and Wales, populated by 7,000 monks and 2,000 nuns. There were also 35,000 lay brethren (servants) that did most of the manual labour. (18) The survey revealed that the total annual income of all the monasteries was about £165,500. The eleven thousand monks and nuns in this institutions also controlled about a quarter of all the cultivated land in England. The six lawyers provided detailed reports on the monasteries. According to David Starkey: "Their subsequent reports concentrated on two areas: the sexual failings of the monks, on which subject the visitors managed to combine intense disapproval with lip-smacking detail, and the false miracles and relics, of which they gave equally gloating accounts." (19)

Cromwell was shocked when the reports came back. It was claimed that William Thirsk, the abbott of Fountains Abbey was guilty of "theft and sacrilege, stealing and selling the valuables of the abbey and wasting the wood, cattle, etc of the estates". He was also claimed that he kept "six whores". The canons of Leicester Abbey were accused of homosexuality. The prior of Crutched Friars was found in bed with a woman at eleven o'clock on a Friday morning. The abbot of West Langdon Abbey was described as the "drunkenest knave living." (20)

Nuns were also criticised in these reports. The agent who visited the Lampley Nunnery claimed that "Mariana Wryte had given birth three times, and Johanna Snaden, six". At the religious house in Lichfield "two of the nuns were with child". Elizabeth Shelly, the Benedictine Abbess of St Mary's Abbey and Christabel Cowper, Benedictine Prioress of Marrick Priory, both received good reports but forty-three nunneries, more than one third of the whole, were threatened with being closed. (21)

Thomas Cromwell's first reaction to the reports was to remove the person in charge of the monastery. For example, when the prior of Winchester Cathedral Priory resigned, the visitor, Thomas Parry, suggested he should be replaced by William Basing, a monk of the house of the "better sort", as his replacement. Cromwell was aware that Basing was a reformer who "favoured the truth" and acted upon his advice.

William Thirsk, the abbott of Fountains Abbey was replaced by Marmaduke Bradley who was a "right apt man" for the post. However, Cromwell had difficulty finding enough monks committed to reform, to take over the running of the monasteries. As David Loades has pointed out: "Cromwell's policy towards religious houses underwent a subtle shift of emphasis. From trying to make sure that abbots and priors of a reforming disposition were appointed, he now began to seek for those who would make no difficulty about surrendering their responsibilities. Admittedly these were often the same men, because the task of converting obstinately conservative monks and friars not only proved uncongenial but usually impossible, and those religious of a reforming turn of mind were often the first to seek escape from the imprisonment of their orders." (22)

A Parliament was called in February 1536 to discuss these reports. Initially Henry VIII wanted the closure of monasteries to be done on an individual basis. However, Thomas Cromwell managed to persuade him that it would be better done by Act of Parliament. This would help to unite the country behind the king against the Church. The legislation stated: "the manifest sin, vicious carnal and abominable living is daily used and committed amongst the little and small abbeys, priories and other religious houses of monks canons and nuns where the congregation of such religious persons is under the number of 12 persons." (23)

When the issue was discussed in the House of Lords, the Lutherians, led by Hugh Latimer, recently appointed as the Bishop of Worcester, supported the measure to close the smaller monasteries. Latimer later recalled that when "when their enormities were first read in the parliament house, they were so great and abominable that there was nothing but down with them". (24) The Act for the Dissolution of Monasteries was passed and received royal assent on 14th April. This stated that all religious houses with an annual income of less than £200 were to be "suppressed". (25)

Three out of ten religious houses were closed by the 1536 Act. All precious metals, all altar furnishings and other high-value items such as bells and roofing lead, became the property of the Crown. Royal commissioners arranged for monks and nuns were relocated to religious houses that remained open. They also sold household goods and farm stock and installed new occupiers as Crown tenants. It has been claimed "that the prime interest of the government in the Dissolution was, from start to finish, in the money that could be raised." (26)

Monastery land was seized and sold off cheaply to nobles and merchants. They in turn sold some of the lands to smaller farmers. This process meant that a large number of people had good reason to support the monasteries being closed. Thomas Fuller, the author of The Church History of Britain: Volume IV (1845) has argued that dissolution of the monasteries was of great personal benefit to Thomas Cromwell, Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley, Solicitor-General Richard Rich and Richard Southwell. (27)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Anne Boleyn was one of those who complained about Cromwell's treatment of the monasteries. As Eric William Ives has pointed out: "The fundamental reason for this was disagreement over the assets of the monasteries: Anne's support for the redeployment of monastic resources directly contradicted Cromwell's intention to put the proceeds of the dissolution into the king's coffers. The bill dissolving the smaller monasteries had passed both houses of parliament in mid-March, but before the royal assent was given Anne launched her chaplains on a dramatic preaching campaign to modify royal policy.... Cromwell was pilloried before the whole council as an evil and greedy royal adviser from the Old Testament, and specifically identified as the queen's enemy. Nor could the minister shrug off this declaration of war, even though, in spite of Anne's efforts, the dissolution act became law." (28)

Pilgrimage of Grace

In October 1536, a lawyer named Robert Aske formed an army to defend the monasteries. The rebel army was joined by priests carrying crosses and banners. Leading nobles in the area also began to give their support to the rebellion. The rebels marched to York and demanded that the monasteries should be reopened. This march, which contained over 30,000 people, became known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. (28)

Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, was sent to Lincolnshire to deal with the rebels. In a age before a standing army, loyal forces were not easy to raise. (29) "Appointed the king's lieutenant to suppress the Lincolnshire rebels, he advanced fast from Suffolk to Stamford, gathering troops as he went; but by the time he was ready to fight, the rebels had disbanded. On 16th October he entered Lincoln and began to pacify the rest of the county, investigate the origins of the rising, and prevent the southward spread of the pilgrimage, still growing in Yorkshire and beyond. Only two tense months later, as the pilgrims dispersed under the king's pardon, could he disband his 3,600 troops and return to court." (30)

Henry VIII's army was not strong enough to fight the rebels in Norfolk. Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, negotiated a peace with Aske. Howard was forced to promise that he would pardon the rebels and hold a parliament in York to discuss their demands. The rebels were convinced that this parliament would reopen the monasteries and therefore went back to their homes. (31)

However, as soon as the rebel army had dispersed. Henry ordered the arrest of the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace. About 200 people were executed for their part in the rebellion. This included Robert Aske, William Thirsk and Lady Margaret Bulmer, who were burnt at the stake in June 1537. Gardiner accepted these decisions but suggested that Henry followed a new policy of making concessions to his subjects. Henry's response was furious. He accused Gardiner of returning to his old opinions, and complained that a faction was seeking to win him back to their "naughty" views. (32)

In the winter of 1537 Thomas Cromwell sent out his commissioners to discover the loyalty of the people who were running the remaining monasteries. Richard Whiting, the Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, was interviewed by Richard Layton, Thomas Moyle, and Richard Pollard. They were not convinced about Whiting's answers and he was sent to the Tower of London. They discovered a book condemning Henry VIII's divorce from Catherine of Aragon. They also discovered evidence that Whiting hid a number of precious objects from Cromwell's agents. (33)

Whiting was sent back to Somerset in the care of Richard Pollard and reached Wells on 14 November. "Here some sort of trial apparently took place, and next day, Saturday, 15th November, he was taken to Glastonbury with two of his monks, Dom John Thorne and Dom Roger James, where all three were fastened upon hurdles and dragged by horses to the top of Toe Hill which overlooks the town. Here they were hanged, drawn and quartered, Abbot Whiting's head being fastened over the gate of the now deserted abbey and his limbs exposed at Wells, Bath, Ilchester and Bridgewater." (33x1)

The commissioners relied heavily on information from local people. William Sherburne, a former friar, accused Robert Hobbes, the Abbot of Woburn Abbey, of being a supporter of the rebels. Hobbes was interviewed and he refused to recant: "Hobbes held firm, although in some places it is difficult to establish an exact meaning from the long and rambling depositions of a man physically ill from strangury, and to disentangle apologies for bluntness of speech from repentance on points of principle. It is certain, however, that to the very end he remained opposed to the suppression of the monasteries, the distribution of ‘wretched heretic books’ by Cromwell, and the royal divorce, all sufficient to make his conviction a formality. Indeed, he confessed his offences and offered no defence." Hobbes was hanged, drawn, and quartered outside the abbey and its land and property was given to the Crown. (34) The heads of two other large houses in Colchester Abbey and Reading Abbey were also executed. (35)

Religious Shrines

In January 1538, Thomas Cromwell turned his attention to religious shrines in England. For hundreds of years pilgrims had visited shrines that contained important religious relics. Wealthy pilgrims often gave expensive jewels and ornaments to the monks that looked after these shrines. Cromwell persuaded Henry to agree that the shrines should be closed down and the wealth that they had created given to the crown. Commissioners were sent round the country to seize relics and shrines.

As Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has pointed out: "The images of the Virgin were taken down from shrines in Ipswich, Walsingham and Caversham; they were carried in carts to Smithfield and burned. The blood of Hailes, popularly believed to be the blood of Christ, was revealed to be a mixture of honey and saffron... It was soon decreed that there must be no more 'kissing or licking' of supposed holy images." (36) Bishop Nicholas Shaxton urged the destruction of all "stinking boots, mucky combs, ragged vestments... locks of hair, and filthy rags, gobbets of wood under the name of parcels of the holy cross." (37)

Henry VIII always believed that as Thomas Becket had disobeyed Henry II and had no right to be a saint. Moreover his shrine was the richest in England. (38) Orders were given to destroy the St. Thomas Becket's Shrine. It is claimed that chests of jewels were carried away so heavy that "six or eight strong men" were needed to carry each chest. (39) The previous year Henry VIII had visited the shrine in order to pray for the birth of a healthy son. (40) On 17th December 1538, the Pope announced to the Christian world that Henry VIII had been excommunicated from the Catholic church.

Henry now had nothing to lose and he closed down the rest of the monasteries and nunneries in England, Wales and Ireland. All told. Henry closed down over 850 monastic houses between 1536 and 1540. Those monks and nuns who did not oppose Henry's policies were granted pensions. However, these pensions did not allow for the rapid inflation that was taking place in England at that time and within a few years most monks and nuns were in a state of extreme poverty.

It has been argued by A. L. Morton that the actions of Thomas Cromwell helped to ensure the success of religious reform: "A few schools were founded out of the spoil, a little was used to endow six new bishoprics. The rest was seized by the crown and sold to nobles, courtiers, merchants and groups of speculators. Much was resold by them to smaller landowners and capitalist farmers, so that a large and influential class was created who had the best of reasons for maintaining the Reformation settlement. This dispersal of the monastic lands by the government was poor economics, but politically it was a master-stroke." (41)

George M. Trevelyan has argued that Henry did not, as it is sometimes stated, distribute any large proportion of the monastic lands and tithes among his courtiers. "He sold much the greater part of them. He was driven by his financial necessities to sell, though he would have preferred to keep more for the Crown. The potential value of the estates, enjoyed in times to come by the lay purchasers or their heirs, was very great compared to the market prices they had actually paid to the necessitous King... Therefore the ultimate beneficiary of the Dissolution was not religion, not education, nor the poor, not even in the end the Crown, but a class of fortunate gentry." (42)

Primary Sources

(1) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

The monasteries of early Tudor England had still not recovered from the Black Death which had halved their population and wiped out some communities altogether. Monastic revenues were now so large, relative to the number of monks, that they encouraged worldliness, and the reports of episcopal visitors in the century preceding the Dissolution show how standards were declining. Feasting had replaced fasting, dress was extravagant, services were poorly attended.... Feasting had replaced fasting, dress was extravagant, services were poorly attended... In charity and hospitality the same decline is recorded. Almsgiving may have averaged the stipulated one-tenth of monastic revenues, but it was indiscriminate and did little to relieve the genuine problem of poverty.

(2) Extracts from the Henry VIII's report on Monastic Houses (1535)

Lampley: "Mariana Wryte had given birth three times, and Johanna Snaden, six"

Lichfield: "two of the nuns were with child"

Whitby "Abbot Hexham took his cut at the proceeds from piracy"

Bradley: "prior hath six children"

Abbotsbury: "abbot wrongfully selling timber"

Pershore: "monks drunk at mass"

(3) Peter Ackroyd, Tudors (2012)

There were in all eighty-six questions... "Whether the divine service was kept up, day and night, in the right hours?"; "Whether they (monks) kept company with women, within or without the monastery?"; "Whether they had any boys lying by them?; "Whether any of the brethren were incorrigible?" "Whether you do wear your religious habit continually, and never leave it off but when you go to bed?"...

One prior was accused of preaching treason and was forced to his knees before he confessed. The abbot of Foundations kept six whores... The canons of Leicester Abbey were accused of buggery. The prior of Crutched Friars was found in bed with a woman at eleven o'clock on a Friday morning. The abbot of West Langdon was described as the "drunkenest knave living".

(4) David Loades, Thomas Cromwell (2013)

One of the major decisions of 1536, which involved both Cromwell and the king, was the dissolution of the minor monasteries. The former had been originally of the opinion that this should proceed on an individual basis, as had been done by Wolsey, but by the beginning of 1536 had been persuaded that it would be better done by Act of Parliament. This may well have been for the purpose of demonstrating that the country was behind the king in this exercise of the Royal Supremacy, and Henry would have been easily convinced for the same reason. The reports of the commissioners, who had been visiting the religious houses since the previous year, provided an adequate excuse...

Consequently all religious houses with an income of less than £200 a year were to be dissolved and their assets given to the king. This he was able to steer safely through both houses, and it received the royal assent on 14 April, coming into immediate effect. A companion statute, passed at the same time, established a Court of Augmentations to administer this property on the king's behalf, and this also bears the unmistakable marks of its origin in the secretary's office, because it formed a key element in his reorganisation of the financial administration, and because the first officers of the court all had close associations with Cromwell. Queen Anne Boleyn was opposed to this secularisation of the monastic properties, arguing forcefully that the proceeds should be used for religious purposes, such as education, and it may be that the new parliament, which met in June, was called partly to resolve this disagreement.

(5) Gilbert Huddleston, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912)

Whatever the charge, however, Whiting was sent back to Somerset in the care of Pollard and reached Wells on 14 November. Here some sort of trial apparently took place, and next day, Saturday, 15 November, he was taken to Glastonbury with two of his monks, Dom John Thorne and Dom Roger James, where all three were fastened upon hurdles and dragged by horses to the top of Toe Hill which overlooks the town. Here they were hanged, drawn and quartered, Abbot Whiting's head being fastened over the gate of the now deserted abbey and his limbs exposed at Wells, Bath, Ilchester and Bridgewater. Richard Whiting was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in his decree of 13 May, 1895.

Student Activities

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)